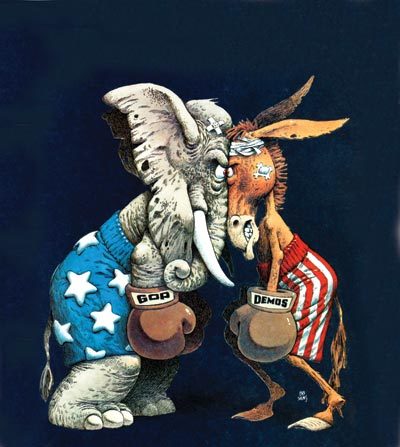

The Politics of Rage

America has witnessed heated presidential campaigns before, but seldom with the level of vociferous anger being expressed this year. While much of the rage seems to be directed at “others” — Mexicans, Muslims, and immigrants from all over — many have pointed out that its true source is the enormous social and economic shift brought about by technology. As author Michael Kimmel argues in his book Angry White Men, many voters feel “betrayed by the country they love, discarded like trash on the side of the information superhighway.”

Where does reasonable anger at bad luck or circumstance end and irrational hatred begin? For historical perspective, a lesson can be drawn from World War II, when rage against the Japanese bubbled over following the attack on Pearl Harbor. At the time, motion pictures, cartoons, and propaganda depicted the Japanese as buck-toothed, semi-human caricatures. No less a figure than General John L. DeWitt, head of the Western Defense Command, told Congress at the time, “The Japanese are an enemy race. We must worry about the Japanese all the time until [they are] wiped off the face of the map.”

Even at the height of World War II, most Americans were outraged by such rhetoric. In a 1943 editorial, the Post lauded “the wave of indifference which greeted the recent effort of a small group of super-duper patriots to make the rest of us feel guilty for not hating the enemy enough.”

More hate, the editors pointed out, was not an answer to the world’s problems, nor would it lead the Allies to victory:

“Undoubtedly, there are plenty of reasons to hate our enemies. Those who know what the Japanese have done to captured soldiers and civilians could not exclude hate from their hearts if they wanted to. But this has not much to do with winning the war, and certainly nothing at all to do with making the peace.”

“We wonder why people deplore our lack of interest in hatred,” added Pacific-based Staff Sergeant Hobert Skidmore in an article published a few months later. Speaking for his fellow soldiers, he continued, “We know the quality of hatred. But charity is greater in us than hatred. [Anger] is not an abiding and continued feeling. It is the thing that makes a soldier in combat achieve the nearly impossible. But it must be controlled. An angry man has his guard down. He endangers himself and the other members of his ship, or plane, or gun crew, or foxhole. There is a word we have in the Army for a guy who is always filled with anger and hatred. It isn’t a pretty word.

“At the right time and for the right thing, anger is valuable. A continuing hatred isn’t worth a damn. Do our civilian law officers hate criminals and lawbreakers? No, they have contempt for them and arrest them and punish them. It is a very satisfactory and democratic solution.

“Hatred we know. We are fighting an enemy capable of hatred. They really loathe us and no fooling about that. They hate us with a blind fury: You probably have noticed that they are losing the war, will lose the peace, will lose something the people of a nation should never lose.”

Today, as campaign rhetoric becomes increasingly inflamed, these reasonable words bear repeating.

Research by Saturday Evening Post archivist Jeff Nilsson.

The Politics of Rage

As the election season advances and campaign rhetoric gets more heated, candidates will be tempted to make more attention-grabbing statements.

The war on terror is sure to be part of the debate. We can expect candidates’ promises to be more ruthless in preventing terror attacks, while criticizing their opponent for being “weak” on extremists.

Already we’re hearing plans to match the radical Islamists’ barbarity, and attack our enemies, and suspected enemies, with a fury that has never been part of American policy.

History offers us a lesson in the politics of rage. Over the centuries we’ve seen that indulging hatred has consistently failed to achieve long-term success. During the Second World War, for example, when the U.S. was fighting two global powers, some Americans said we needed to hate more to achieve victory.

In a 1943 editorial, the Post editors had an interesting response to this call for hatred. They praised the Americans’ indifference to “the recent effort of a small group of super-duper-patriots to make the rest of us feel guilty for not hating the enemy enough. More hate, it was urged, was needed if we were to win the war.” Hating more, the editors continued, would probably not help America win the war any sooner.

In fact, hating might send the country off in the wrong direction, according Staff Sergeant Hobert Skidmore. Stationed on the war’s front lines, on “a far-away island in the Pacific,” he believed America couldn’t afford the luxury of hatred or vengeful violence.

In his Post article, “We Don’t Need to Hate,” he agreed that anger had its uses. It gave soldiers in combat the courage and strength they needed to achieve the nearly impossible. “But it must be controlled. An angry man has his guard down. He endangers himself and the other members of his ship, or plane, or gun crew or foxhole. There is a word we have in the Army for a guy who is always filled with anger and hatred. It isn’t a pretty word.”

American anger would have been at an all-time high when Skidmore’s article was published. The Japanese had just begun launching kamikaze attacks, pilots flying their explosive-laden aircraft into U.S. war vessels.

But Skidmore cautioned Americans against giving in to hatred: Blind fury was the sign of desperation and impending defeat. And once a nation gave in to savagery, it lost its self-respect, along with its respect for other nations.

|

|

|