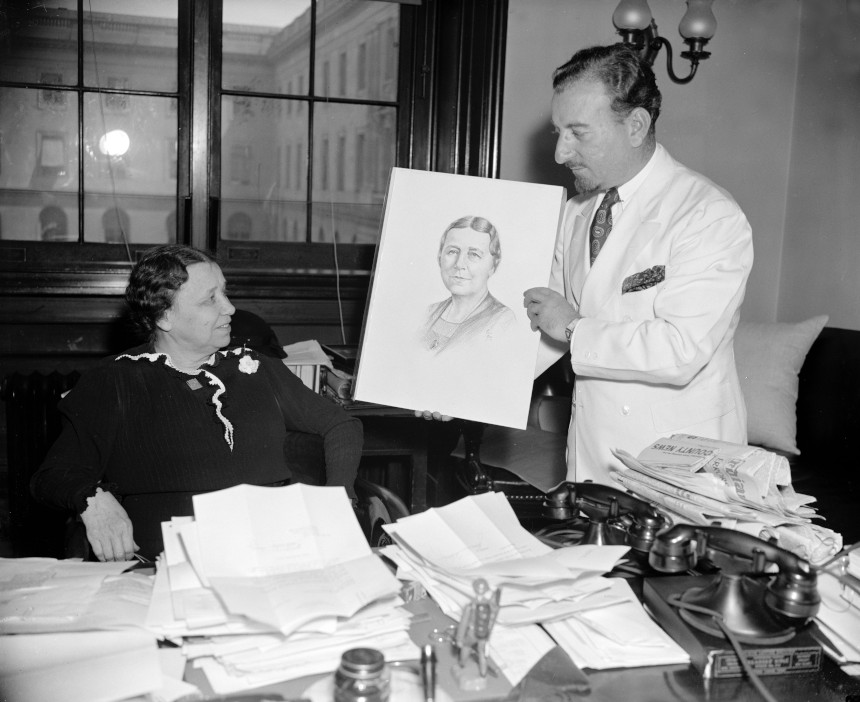

Mrs. Caraway Goes to Washington

The first woman elected to the U.S. Senate is not a household name. That woman, Hattie Wyatt Caraway of Arkansas, kept a very low profile. She is not considered a political trailblazer. Indeed, she voted with the rest of the Southern delegation against the Anti-Lynching Bill of 1934, intended to make lynching a federal crime. But though her name has become a historical footnote, Caraway, who was born in the shadow of post-Civil War Reconstruction and died at the dawn of the atomic age, offers a fascinating study in the challenges facing women in American politics.

Caraway won a special election to the Senate in 1931 after the death of her husband, Democratic Senator Thaddeus Caraway. This was not without precedent for a politician’s widow, because the move allowed the “real candidates” — the men — time to prepare their campaigns. But Caraway, at age 54, shocked the powers-that-be by announcing her plans to run in the 1932 general election.

In making the decision to run for a full term in the Senate, she knew she was breaking new ground for women. Until Caraway’s election, only one other woman had even set foot in the Senate, the self-styled “World’s Most Exclusive Club”; in 1922, 87-year-old Rebecca Felton had been allowed to sit in the chamber for a day as reward for her political contributions in Georgia. Though the 19th Amendment guaranteeing American women the right to vote had been ratified, the idea that government was a man’s sphere had not changed much since abolitionist and women’s rights advocate Sarah Grimké visited the U.S. Supreme Court years earlier in 1853. After Grimké was invited to sit in the Chief Justice’s chair, she stated that someday the seat might be occupied by a woman. In response, “the brethren laughed heartily,” she later recounted in a letter to a friend.

A widespread criticism of Caraway as she entered the 1932 campaign was that she was needed at home to take care of her children, even though they were already grown.

But in 1932, the year the Dow Jones hit its lowest point during the Great Depression, few Americans were laughing. Caraway, a small woman who always dressed in black after her husband’s death, could have easily passed as someone’s visiting grandmother in the halls of the Capitol. Her only previous elected experience was serving as the secretary of a small-town women’s club. But desperate constituents in Arkansas didn’t seem to care who she was, as long as she could help them.

Letters poured into Caraway’s Senate office, pleading for relief. As she read them and observed the action — or inaction — of fellow senators, she came to a startling revelation: Wasn’t a person — any person, even a woman — of moderate intelligence who worked hard, cared about average people, and stayed awake at their Senate desk (many colleagues didn’t) just as useful as those who made bombastic speeches?

Caraway’s three sons, West Pointers and high-ranking Army officers, supported her political aspirations. As she wrote in her journal entry of May 9, 1932, the first time she announced her decision to run: “Well, I pitched a coin and heads came three times, so because [my sons] wish and because I really want to try out my own theory of a woman running for office, I let my check and pledges be filed. And now won’t be able to sleep or eat.” Within two days’ time, though, Caraway seemed to have made peace with the decision, writing in her journal that she would “have a wonderful time running for office” if she could hold on to her dignity and sense of humor. During the campaign, she would need both.

A widespread criticism of Caraway as she entered the 1932 campaign was that she was needed at home to take care of her children, even though they were already grown. Sexism aside, Caraway’s campaign faced another problem: She had no money to run. But she did have a good friend in the flamboyant Louisiana politician Huey Long.

Long genuinely liked Caraway after spending time sitting next to her in the back row of the Senate, and he didn’t have much to lose by throwing his support behind her. Even if Caraway lost, it would not really be considered his fault since the odds were against her winning anyway. But if he were to help her get elected, he would emerge as a political miracle worker, and maybe even secure a rubber stamp for his pet programs. At the very least, he’d gain some ground in his power struggle with Arkansas’s other Senator, Joe T. Robinson.

With Long’s support, Caraway did win the 1932 election for a full term in the Senate, earning more total votes than all six men who ran against her put together. Some political observers said she would not have won without Huey’s help, but she notably defeated her opponents in counties where she and Long did not campaign.

In office, Caraway was dubbed “Silent Hattie” because she rarely delivered the thunderous orations her male colleagues were known for. It should be noted that there were male senators who declined to make speeches as well, but it was Caraway whose silence was labeled.

If she was quieter than most, her record spoke for her. As a senator, she worked tirelessly, earning a reputation as an effective public servant in the troubled times of the Great Depression and World War II. A saying among Arkansans became, “Write Senator Caraway. She will help you if she can.”

Caraway did her best work in committee, where she could speak normally without having to orate from the well of the Senate chamber. In this small setting, she could work to convince others of what average people needed, like flood control. She had seen the devastation in her state when roaring waters washed away entire communities during the Great Flood of 1927, the most destructive flood ever to hit the state and one of the worst in the history of the nation.

In office, Caraway was dubbed “Silent Hattie” because she rarely delivered the thunderous orations her male colleagues were known for.

When Caraway first ran for office, she ran on the premise that the nation could be served by an average person who knew the price of milk and bread, and who remembered there were people who had none. She walked her talk, carrying her lunch in a brown paper bag, and starting each day by reading every word of the Congressional Record. She never missed a Senate vote or a committee meeting. Nor did she take time away from Congress to campaign, as others did.

In time, she proved to herself that she had a mind as good as anyone’s in the Senate. While serving on the Senate’s Agriculture Committee, for instance, something that was important to her rural state, she realized that she knew firsthand about issues that affected farmers more than what she called in her journal the “manicured men” of the Senate.

The voters of Arkansas, in turn, stood by her. Caraway was reelected in 1938, defeating a strong candidate whose campaign slogan boomed “Arkansas Needs Another Man in the Senate!” She therefore became not only the first woman to be elected to the Senate, but also the first to be reelected. Among her many firsts serving in the Senate from 1931 to 1945, she also became the first to preside over the Senate, chair a Senate committee, and lead a Senate hearing.

But it wasn’t easy being the only woman in the room. Caraway was often ignored by her fellow senators, and she had no mentor. Her position must have often felt insecure. Arkansas’s other senator, the powerful Joe T. Robinson, had very few interactions with her. She presumed it was because he was waiting for a “real” senator — a man — to arrive. Several of her journal entries reflect their terse relationship. On January 4, 1932, soon after Caraway entered the Senate, she wrote that Robinson “came around only for a moment at the instigation” of his chief-of-staff. On May 19, 1932, Robinson inspired her to write, “I very foolishly tried to talk to Joe today. Never again. He was cooler than a fresh cucumber and sourer than a pickled one.” Reflecting on their strained relationship, she once poignantly confessed in her journal, “Guess I said too much or too little. Never know.”

If she felt invisible in the Senate chambers, she was very aware that the press held her in the spotlight. At one point, she wrote in her journal, “Today I almost made the front page as I lost the hem out of my petticoat.” But Caraway didn’t view herself as a firebrand. Rather, she conducted herself as she believed a “Southern lady” would do. In her journal, she notes that she did not appreciate when a reporter “pushed into” her office. “I was terribly indignant,” Caraway wrote. “She got no interview.”

Still, in 1943, she notably cosponsored the Equal Rights Amendment, a piece of legislation that had already been introduced in Congress 11 times and failed each time. The proposal simply read, “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

Caraway was also one of the sponsors of what has been called the most momentous piece of legislation in American history, the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, popularly known as the GI Bill. In doing so, she put herself up against powerful congressmen who condemned the bill for being “socialist.” But Caraway, who came from a struggling farm family herself (she had only been able to go to college thanks to the generosity of a maiden aunt), firmly supported the piece of legislation, which contained educational benefits for World War II veterans. She saw it as a manifestation of her belief that education was the key to progress.

By 1944, however, Caraway’s style no longer resonated with voters in the same way. During her bid for reelection, she placed fourth in the Democratic primary. The winner, J. William Fulbright, a wealthy former Rhodes scholar, went on to secure the general election and would serve as a powerful force in the Senate for the next 30 years.

On Caraway’s final day in the Senate in 1945, her years of service earned her the rare standing ovation by her all-male colleagues. Yet, even as they honored her, a statement — which was no doubt meant as a compliment — offers a telling window into what it was like to be the first. “Mrs. Caraway,” one of the men proclaimed, “is the kind of woman senator that men senators prefer.”

More than a half-century after Caraway’s death in 1950, the challenging reality of her precarious position as the first woman to break into the “World’s Most Exclusive Club” still resonates. A few years ago, I was sitting next to Arkansas Senator Blanche Lincoln at a speaking engagement when the Senator opened her daily planner. Inside the front cover, where she would see it immediately, Senator Lincoln had written the words Caraway had written in her diary when she decided to run for the first time: “If I can hold on to my sense of humor and a modicum of dignity I shall have a wonderful time running for office, whether I get there or not.”

Nancy Hendricks writes extensively on women’s history and is the author of Senator Hattie Caraway: An Arkansas Legacy.

Originally Appeared at Zócalo Public Square

This article is featured in the November/December 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Library of Congress