Your Weekly Checkup: Caffeine and the Heart

“Your Weekly Checkup” is our online column by Dr. Douglas Zipes, an internationally acclaimed cardiologist, professor, author, inventor, and authority on pacing and electrophysiology. Dr. Zipes is also a contributor to The Saturday Evening Post print magazine. Subscribe to receive thoughtful articles, new fiction, health and wellness advice, and gems from our archive.

Order Dr. Zipes’ new book, Damn the Naysayers: A Doctor’s Memoir.

During more than 50 years of practicing cardiology, I have counseled hundreds, if not thousands, of patients complaining of palpitations and heart rhythm problems to reduce or eliminate intake of caffeinated beverages, particularly coffee. Caffeine, the major ingredient in coffee, is a known stimulant that triggers the body’s fight or flight response, with an outpouring of adrenaline and other substances. Three fourths of my physician colleagues proffer the same recommendation. Despite caffeine’s stimulating action, recent evidence suggests we may have been wrong.

An extensive review of multiple studies concluded that, barring about 25% of individual cases that exhibit a clear temporal association between heart rhythm episodes and caffeine intake, coffee and tea appear to be safe. A regular intake of up to three cups of coffee a day may even protect against heart rhythm disorders [PDF]. One large study of 228,465 participants showed that the incidence of atrial fibrillation decreased by 6 percent for every three cups of coffee a day. Another study of 115,993 patients showed a 13 percent reduction in the risk of atrial fibrillation.

One report concluded that drinking three to four cups of coffee daily compared with no coffee intake reduced death and cardiovascular disease by almost 20 percent. Coffee was also associated with a reduced risk of some cancers and neurological and liver disorders. Interestingly, patients with Parkinson’s disease had significantly lower serum concentrations of caffeine and its metabolites than subjects without the disease, despite consuming the same amount of caffeine. It’s not known whether this response might be due to the drugs they were taking or a specific effect of early Parkinson’s disease on caffeine metabolism.

Energy drinks are in a different class. They often contain caffeine at significantly higher concentrations than coffee and tea, along with other energy-boosting substances, such as guarana, sugar, ginseng, yohimbine, and ephedra. Guarana, particularly, has a higher caffeine concentration than coffee and contains theophylline, which also has stimulant properties. Multiple reports relating the temporal association between ingesting energy drinks and heart rhythm problems, including sudden death, are of major concern. Energy drinks may also increase the risk of blood clots. My recommendation is to avoid all energy drinks.

Some caution about accepting these positive results is advised since extrapolating data from healthy volunteers in the studies to individual patients can be risky. Differences in individual susceptibility to the effects of caffeine, various health conditions, and drugs could trigger caffeine-induced heart rhythm problems, so those with a clear temporal association between coffee intake and heart rhythm episodes should abstain. A transient blood pressure rise can occur in susceptible individuals. Also, caffeine tolerance developed by regular long-term coffee drinkers may explain some of the lack of association with heart rhythm problems. For example, I enjoy a double espresso after dinner each night and still fall quickly asleep (the wine helps!), but I have been drinking coffee regularly for many years and would not recommend this for new coffee drinkers.

In conclusion, those of you who are coffee and tea lovers can rest assured that, along with dark chocolate and red wine, caffeine intake is likely to be safe, and maybe even beneficial.

But wait! This column is mostly about caffeine and the heart. What about caffeine and cancer? See next week’s column.

Your Weekly Checkup: Managing Atrial Fibrillation

“Your Weekly Checkup” is our online column by Dr. Douglas Zipes, an internationally acclaimed cardiologist, professor, author, inventor, and authority on pacing and electrophysiology. Dr. Zipes is also a contributor to The Saturday Evening Post print magazine. Subscribe to receive thoughtful articles, new fiction, health and wellness advice, and gems from our archive.

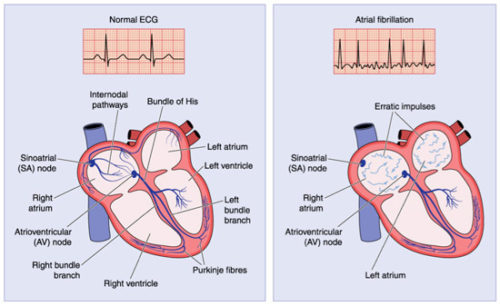

Your heart has four chambers: two on top called the atria, and two on the bottom called the ventricles. Fibrillation, a disorganized, rapid (400+/minute) heart rhythm, can occur in the atria (atrial fibrillation, AF) or the ventricles (ventricular fibrillation, VF). Since fibrillation prevents the heart from contracting and propelling blood forward, it is lethal when it occurs in the ventricles unless stopped by a shock within seconds to a few minutes. Ventricular fibrillation is responsible for a significant number of the 300,000 sudden deaths annually in the U.S.

Atrial fibrillation, on the other hand, is the most common sustained heart rhythm disorder, affecting over 5 million Americans, and expected to increase to more than 12 million by 2030. Though considered a fairly benign arrhythmia (abnormal heart rhythm) for many years, we now realize that AF can also be dangerous, although nowhere as lethal as VF. The incidence of AF increases with age and is associated with an increase of heart failure, sudden death, total mortality, and strokes. A recent study estimated that the lifetime risk for atrial fibrillation is approximately 37% after age 55 years.

Many environmental factors help explain why the incidence of this arrhythmia is approaching near epidemic proportions. Risk factors for developing AF include hypertension, obesity, heart attacks, excessive alcohol consumption, excessive physical training, smoking, stress, diabetes, heart failure, elevated LDL cholesterol, and (perhaps) sleep apnea. Appropriate lifestyle changes that address these risk factors can help reduce AF’s incidence.

Three clinical aspects of the arrhythmia require treatment:

- eliminating the AF and restoring a normal heart rhythm when possible

- controlling the heart rate of the lower chamber (ventricles) if AF persists

- providing anticoagulation to reduce the risk of stroke

Because of these challenging therapeutic decisions in treating AF patients, as well as the complexity of the arrhythmia, treatment may be best handled by a cardiologist in an urban setting. A recent study published in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology concluded that AF patients lived longer when cared for by cardiologists, while another study found that the chance of dying from AF was greater when patients were treated in rural compared with urban hospitals.

The take home message is that AF is frequent, particularly in older folks, and that treatment by skilled medical professionals can either eliminate it or treat it to make it quite compatible with a fairly normal life.