What The Operators Overheard in 1907

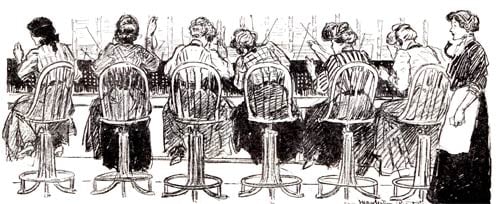

When the Bell System first offered telephone service to subscribers, it hired teenage boys for operators. Now, teenage boys have many virtues, but patience, focus, and the ability to take criticism are not chief among them. When the number of irate customers rose sharply, the company replaced them with women operators.

Women, the company reasoned, were tactful, helpful, dedicated, attentive to details—and they could work harder than most men thought possible. They could deftly handle the callers who became furious when told the number they were calling was busy.

In those days, the job of a telephone operator—also called a “Hello Girl” or “Central”— was far from easy. First, she had to take all responsibility for electric shocks she received from her “operating board.” She also had to memorize the position of 300 phone numbers on the board directly in front of her.

She was expected to use only the language approved by the company. Numbers could be read only one way. (The number 2000 could only be spoken as “two oh, double-oh.” 4001 was “four, double-oh, one.”) The company also directed them to give the time in “railroad style”: not “twelve minutes to nine” but “eight forty-eight.” The rest of her speech was limited to a handful of approved expressions:

“Number?”

“They don’t answer.”

“Line busy.”

“Line out of order.”

“I have no such number; please refer to your directory.”

“Telephone has been taken out.”

“I will give you Information.”

“I will give you Chief Operator.”

Lastly, an operator had to be fast.

Central … takes care of six or seven customers a minute. During the rush hour she supplies 360 connections in 60 minutes; under stress of intense public excitement she has a record of answering 15 calls per minute. [“‘Hello’ Girls” by Harris Dickson, Sept 26, 1908]

There was one small compensation to all the drawbacks of being a “Hello Girl,” according to Dickson:

In her spare time, she dearly loves to listen to telephone chatter—by way of novelty and recreation.

Officially, the Bell Systems didn’t allow operators to listen in to conversations, Dickson reported. (In France, he added, privacy was enforced by the Government.) Operators were prohibited to marry anyone on a long list of forbidden bridegrooms: police employees, detectives, government officials, foreigners, etc. so they wouldn’t be tempted to divulge any secrets they overheard.

The anonymous author of “The Diary of a Telephone Girl: The Work of a Human Spider in a Web of Talking Wires” readily admitted eavesdropping.

There are sometimes long enough intervals … for me to be able to read or write letters. They put on a bell attachment that rings for every call, so I can’t fail to answer.

Of course I had plenty of time for listening, and it was so exciting sometimes that I hated to stop long enough to answer another call.

The other night I switched a friend of mine on to the line, opened his listening key and others in turn, so that for an hour he could overhear all sorts of private conversations, one after the other.

It’s so queer to press down the row of “listening keys” one after another and get bits of the different conversations! Different voices, different dialects, different emotions, tempers, subjects! All sliced off like Neapolitan ice cream—little bits of pulsing human lives. The girls do awfully mean things when they’re exasperated by angry subscribers. You can, for instance, switch three or four couples together—a pair of lovers, maybe, two business men and one woman gossiping to another—and then sit and hear them rage at each other.

It was interesting, too, to notice how the character of the talk changed as the hour grew late. The conversations seemed to grow more familiar and confidential and affectionate toward eleven o’clock.

There are several distinct types that I can recognize immediately and I almost know what they’re going to say.

First, at 7 o’clock, there are scattered calls, usually important, for doctors, perhaps; and you have to ring and ring, because the subscribers hate so to get up and answer the ‘phone.

At 8 o’clock, the nice, early-morning women come on to market with patient, affable butchers. They always want a tender joint and fresh vegetables. “Yes, ma’am!” say the butchers.

At 9, the business man in a hurry, in a loud, violent tone, impatient and cross, bullying the operator, and then, when he gets his number, lowering his voice to an amiable growl.

At 10, interminable conversation between women over the “flat-rate” ‘phones with infinite details as to clothes. There’s no five-minute limit to talks with this company and you can’t cut them off. I’ve known them to keep it up for three-quarters of an hour. [Imagine: talking on the phone for 45 minutes!—ed.]

At 11 to half-past there’s a lull, punctuated, perhaps, by nippy ladies calling up employment agencies [looking to replace a servant], or stupid servant girls replying.

At 11:30 till 12:30 there’s a wild rush, everybody trying to catch everybody else for lunch.

From then till 3 or so there are characteristic calls of all sorts: peevish, hurried females who use the nickel ‘phones in the downtown drug stores, and who have just got to have their numbers; silly schoolgirls mischievously calling up men they don’t know; sporting men [placing bets] in an unintelligible racing jargon, and so on.

From 3 to 4 it slows down again. Then there’s likely to be a flurry of women trying to call up stores before they close, or in time to catch the last deliveries.

At 5, wives begin to call up to know if husbands are coming home, and if not, why not? Apologetic replies from offices as business men attempt to explain. Or, if he’s coming, “Be sure to bring home a steak or a lobster.” He (in disgust): “Why couldn’t you have ordered them this morning?”

From 6 till 7 everybody seems to be too busy to call up, except the younger people, girls and youths, who joke and [plan to meet later]. This is a good hour, too, for the obsequious underling, the club hallboy or the clerk of a garage, who has taken orders and been respectful all day, to talk down to the telephone operator. Now, along toward 8, comes the nervous maiden, calling up her men, too uncertain of their reception to bully Central as she usually does.

From 9 on not many calls.

After 10:30 come the calls [for taxis and chauffeurs] and the hotel private exchanges begin to get busy.

Then, at 11 and on through till 2, the reporters with strange tales.

I hate the reporters. They always have the most thrillingly interesting conversations, but if I listen on the line they always know it and get mad. “ Get off the line, Central,” they say, “or I’ll stop talking!” No matter how softly I press back my listening key, they seem to know I’m listening, and then they talk so horridly that I simply have to shut the key.

With automation replacing most phone operators, there are far fewer people to eavesdrop on your conversation. Besides, the whole idea of private phone conversations seem quaint in an age of cell phones. You don’t need to become an eavesdropping operator when callers walk through airports and stores handing out free samples of their private lives.