Considering History: Operation Paperclip and Nazis in America

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

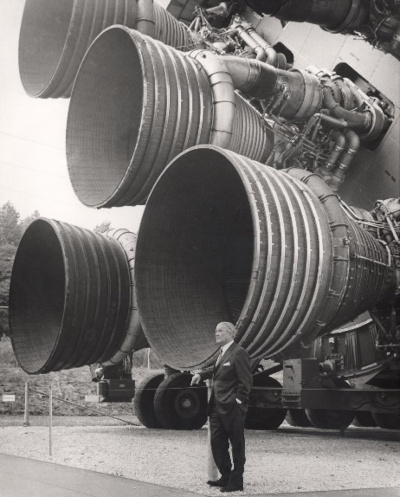

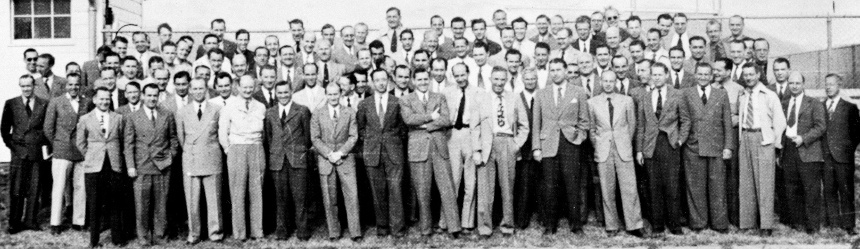

On September 20, 1945, the infamous Nazi scientist Wernher von Braun arrived at Fort Strong, a U.S. military site on Long Island in Boston Harbor. In a period when many of von Braun’s Nazi colleagues were preparing to be tried in the Nuremberg war crimes trials that would commence exactly two months later, von Braun and other Nazi scientists were instead being brought to the United States to serve as prized members (and often leaders) of teams researching the space program, weapons technology, and other initiatives. Known as Operation Paperclip, this secret endeavor, led by the federal government’s newly created Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency (JIOA), would eventually bring more than 1600 German scientists — many of them former Nazis — to America between 1945 and 1959.

The Soviet Union was similarly pursuing Nazi scientists for its own weapons and space programs, and so Operation Paperclip can be framed as part of the incipient Cold War, a reflection of how quickly and thoroughly the two nations pivoted from their tenuous World War II alliance to this new, multi-decade conflict. Yet at the same time, the relationship between the U.S. government and these Nazi scientists cannot be separated from the longstanding, deeply rooted presence of Nazis and antisemitism in America. From prominent figures and voices to mass movements and rallies, the two decades leading up to World War II featured numerous connections between Americans and Nazi Germany, links that reveal that Nazism was never simply a foreign or enemy force.

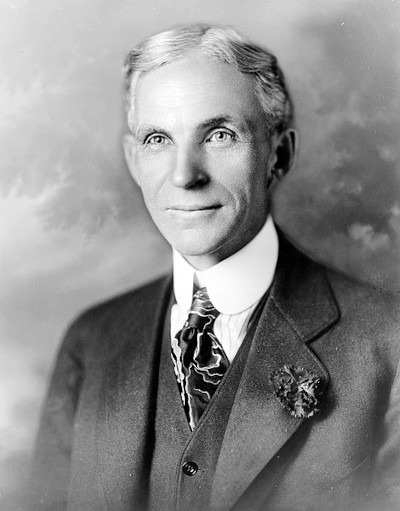

One of those Americans with close ties to Nazi Germany was also one of the most successful and famous Americans of the early 20th century: Henry Ford. The automobile inventor and entrepreneur wasn’t just a strident anti-Semite—he was apparently an influence on the rise of German Nazism and even Adolf Hitler himself. Between 1920 and 1927, Ford and his aide Ernest G. Liebold published The Dearborn Independent, a newspaper that they used principally to expound anti-Semitic views and conspiracy theories; many of Ford’s writings in that paper were published in Germany as a four-volume collection entitled The International Jew, the World’s Foremost Problem (1920-1922). Heinrich Himmler wrote in 1924 that Ford was “one of our most valuable, important, and witty fighters,” and Hitler went further: in Mein Kampf (1925) he called Ford “a single great man” who “maintains full independence” from America’s Jewish “masters”; and in a 1931 Detroit News interview, Hitler called Ford an “inspiration.” In 1938, Ford received the Grand Cross of the German Eagle, one of Nazi Germany’s highest civilian honors.

After his 1927 solo flight across the Atlantic, aviation pioneer Charles Lindbergh was another of the period’s most famous Americans, and in 1938 Lindbergh likewise received a Cross of the German Eagle in 1938, this one from German air chief Hermann Goering himself. Over the next two years, Lindbergh’s public opposition to American conflict with Nazi Germany deepened, and despite subsequent attempts to recuperate that opposition as fear over Soviet Russia’s influence, Lindbergh’s views depended entirely on anti-Semitic conspiracy theories that equaled Ford’s. In a September 1939 nationwide radio address, for example, Lindbergh argued, “We must ask who owns and influences the newspaper, the news picture, and the radio station, … If our people know the truth, our country is not likely to enter the war.” Seen in this light, Lindbergh’s role as spokesman for the era’s America First Committee makes clear that that organization’s non-interventionist philosophies during World War II could not and cannot be separated from the antisemitism and Nazi sympathies of figures like Lindbergh and Ford.

American Nazism was much more than just a perspective held by elite anti-Semites — it was very much a movement. And like so many problematic social movements, it featured a demagogic voice to help spread its alternative realities — in this case, the Catholic priest turned radio host Charles Edward Coughlin. By the time World War II began, Coughlin had been publicly supporting both Nazi Germany and anti-Semitic conspiracy theories for years; his weekly magazine, Social Justice, ran for much of 1938 excerpts from the deeply anti-Semitic Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a text that contributed directly to Hitler’s views and the Holocaust. Both Social Justice and Coughlin’s radio show were hugely popular throughout the 1930s — a separate post office was constructed in his hometown of Royal Oak, Michigan just to process the roughly 80,000 letters he and show received each week—illustrating that American Nazism and anti-Semitism were widespread views in the period.

No moment reflected that American movement better than the February 20, 1939 rally that brought more than 20,000 Nazi supporters to New York’s Madison Square Garden. The rally was put on by the German American Bund, a national organization which consistently sought to wed pro-Nazi Germany sentiments to direct appeals to mythic images of American identity and patriotism. To that end, the rally was held on George Washington’s birthday, and the stage featured a portrait of Washington flanked by both American flags and Nazi flags/swastikas. After the rally opened with a performance of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” Bund secretary James Wheeler-Hill proclaimed in his introductory speech that “If George Washington were alive today, he would be friends with Adolf Hitler.” And in his closing speech, Bund leader Fritz Julius Kuhn went further, arguing that “The Bund is open to you, provided you are sincere, of good character, of white gentile stock, and an American citizen imbued with patriotic zeal.”

Yet many other Americans expressed their patriotic zeal by opposing this Nazi rally. An estimated 100,000 protesters gathered outside the Garden, dwarfing the 20,000 or so Nazi sympathizers inside. The protesters featured World War I veterans, members of the Socialist Workers Party, and countless other local and national organizations and communities. And inside the rally, one young man took such opposition a step further: Kuhn’s speech was interrupted when Isadore Greenbaum, a 26-year-old Jewish-American plumber’s assistant from Brooklyn (and future World War II naval sailor), charged the stage. Greenbaum was attacked by Bund guards, pulled away by police, and charged with disorderly conduct, for which he paid a $25 fine to avoid a 10-day jail sentence. But he was not the least bit apologetic, later stating, “Gee, what would you have done if you were in my place listening to that s.o.b. hollering against the government and publicly kissing Hitler’s behind while thousands cheered? Well, I did it.”

Greenbaum and his fellow protesters make clear that these pro-Nazi sentiments were in no way unopposed in, nor exemplary of, 1930s America. But neither can those figures mitigate the troubling realities of the rally and its reflection of widespread American support for Hitler and the Nazis, support that included some of the nation’s most famous individuals as well as tens of thousands of other Americans. In a moment when Nazi imagery and sentiments have returned to American social and political debates, we would do well to remember their deep roots in our culture.

Featured image: German American Bund parade in New York City in 1937 (Library of Congress)

A Brief History of the Minimum Wage

Recently, CBS News observed that it’s been 11 years since the last federal minimum wage increase, while in the same time period, the cost of living has risen 20 percent, squeezing low-wage workers who are already struggling during the pandemic. We took a look at the history of the minimum wage, controversies surrounding it, and the chances that Washington will raise it anytime soon.

Over 120 bills were sitting President Franklin Roosevelt’s desk on June 25, 1938, waiting for his signature. Somewhere in that stack was a bill that would have a huge impact on American labor. Called the Fair Labor Standards Act, it would, at first, only apply to businesses engaged in interstate commerce, and affect only 20 percent of America’s work force. But it outlawed child labor, set a maximum of 44 hours for a work week, and it guaranteed a minimum wage.

A similar law had been struck down by the Supreme Court in 1935. But the Court reversed itself two years later, and a new bill was sent through Congress. It met opposition from small manufacturers who declared they couldn’t afford to pay their workers the 40¢ an hour wage the law would require. Roosevelt compromised, setting the minimum hourly wage at 25¢ for the first year.

By this time in his administration, Roosevelt was accustomed to the cries of outrage from his opponents. The night before he signed the bill, he told Americans in one of his fireside chats, “”Do not let any calamity-howling executive with an income of $1,000 a day…tell you…that a wage of $11 a week is going to have a disastrous effect on all American industry.”

The following year, the minimum wage was hiked a nickel, to 30¢ an hour. The next raise came in 1945, when inflation followed the increased money supply circulating in the wartime economy. The wage rose to 40¢ an hour.

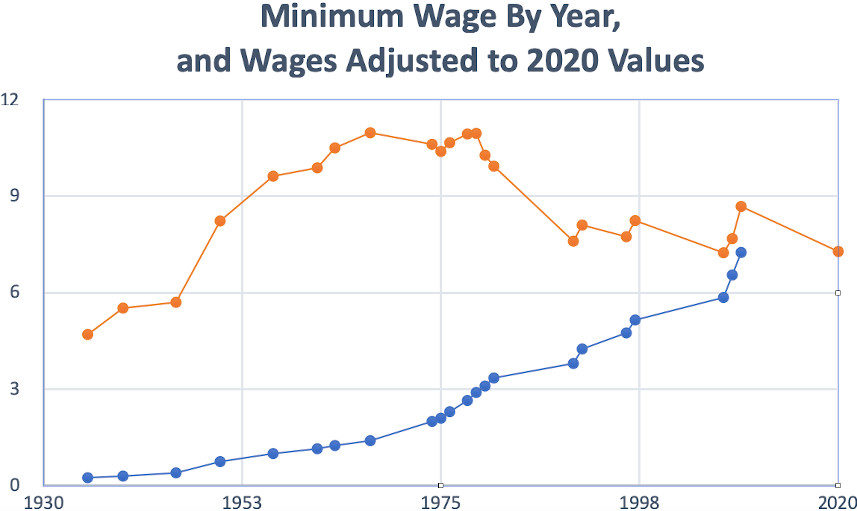

Over the years, the wage level has been lifted to reflect inflation and the rising cost of living. But successive congresses had differing ideas about what a minimum wage should do. Inaction led to the minimum wage often failing to keep pace with inflation, as shown below.

The lower line shows the actual hourly wage over the years. The upper line shown the value of that wage in 2020 dollars. Thus, the purchasing power of the 25¢ earned in an hour’s work in 1938 would be worth $4.70 today.

The highest minimum wage, when you adjust for inflation, was set in 1979, when it reached a value equivalent to $10.95 an hour today. Though increased several times, its relative value has gradually declined in the subsequent 41 years.

Today, a worker earning the federal minimum wage receives $7.28 an hour, before taxes. That wage was established back in 2009, and has set a record for the longest time without a raise. In the 11 years since then, the wage has lost 17 percent of its purchasing power.

Don’t confuse “minimum wage” with a “living wage” — the amount necessary to cover basic living expenses. Professor Amy Glasmeier of MIT has calculated a living wage based on estimated basic costs of food, child care, health care, housing, transportation, and other necessities, and compares it to the local minimum wage and poverty wage.

Poverty wage is lower than the minimum wage. A single person earning less than $12,760 is considered living in poverty. For a family of four, the figure is $26,200.

The poverty line was first calculated in 1955 by determining food expenses took up a third of a family’s budget after taxes. Therefore, the Agriculture Department multiplied food costs by three. The same calculation is used today, though the cost of food is continually adjusted in accordance with the Consumer Price Index.

The poverty wage determination is based on basic living. It doesn’t factor in varying housing or transportation costs. It doesn’t allow for leisure, entertainment, or food outside the Agriculture Department’s regimen of inexpensive meals. It means strict subsistence and no opportunity to save money.

For the average family of two adults and two children in the United States, the living wage is $16.54 per hour, or $68,808 a year. In contrast, the average minimum wage worker earns $15,080 a year.

If you hope to earn the living wage for a family of four, you would need to work almost four full-time jobs. At minimum wage, a single mother of two children would need to work nearly 24 hours a day for six days a week.

According to federal guidelines, two people with a total annual income below $16,910 are legally poor. The New York Times calculated that at least one person would need to earn a minimum of $8.12 an hour to escape the impoverished designation.

Since Washington can’t agree to raise the minimum, many states have stepped in to establish their own. As of 2018, 29 states, including Washington, D.C., have established minimum wages higher than the federal level. For example, Oregon, Washington, and Florida, which adjust their minimum wages to reflect rises in the consumer price index, pay workers between $9.00 and $11.00 an hour.

In addition, some cities have raised their minimum wage even higher. In Seattle, it will be $15.45 per hour next year. Not long ago, San Francisco raised its minimum to $15 per hour, which boosted the salaries of nearly a fourth of the city’s workforce.

There have been repeated efforts to raise the federal minimum wage. Proponents have argued that the current rate does little to help workers. Opponents claim that raising wages would lead to an increase in consumer prices and lay-offs of some workers to pay the higher wages of others. Economists have reported research that both supports and contradicts the various claims.

In 2019, when the House of Representatives passed a bill to raise the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour, the Congressional Budget Office predicted the law would increase the wages of 17 million workers, but put another 1.3 million out of work. The Center for Economic and Policy Research, on the other hand, found little or no change in employment resulting from modest increases in the wage.

One benefit to raising the minimum wage could be increased spending among lower income workers, leading to a higher demand for goods. (This was Henry Ford’s thinking when he raised his minimum wage to a record-breaking $5 a day. “The owner, the employees, and the buying public are all one and the same,” he wrote, “and unless an industry can… keep wages high and prices low, it destroys itself, for otherwise it limits the number of its customers.”)

Another unexpected effect of raising the minimum wage could be the reduction in government spending. According to a UC Berkeley study, over half of fast-food workers rely on public assistance checks to get by. Just raising the minimum wage to $10.10 would eliminate $7.6 Billion in income-support programs.

The prospects for increasing the minimum wage don’t appear good. In the current economic climate, with 10 percent unemployment, the supply of labor exceeds the demand. Workers have little leverage over employers. Businesses, particularly those operating on margins made razor-thin by the recession, will have small motive to increase pay.

A further obstacle is indicated by a recent study by the National Bureau of Economic Research, which found employers often respond to minimum-wage hikes by bringing automation in to take the place of human workers.

The good news, though, is that fewer and fewer Americans are limited to living on that income. In 1980, 17 percent of workers were receiving minimum wage. In 2018, that percentage had dropped to just only 2 percent.

Featured image: Hyejin Kang / Shutterstock

Henry Ford’s Grandson Defends the Car

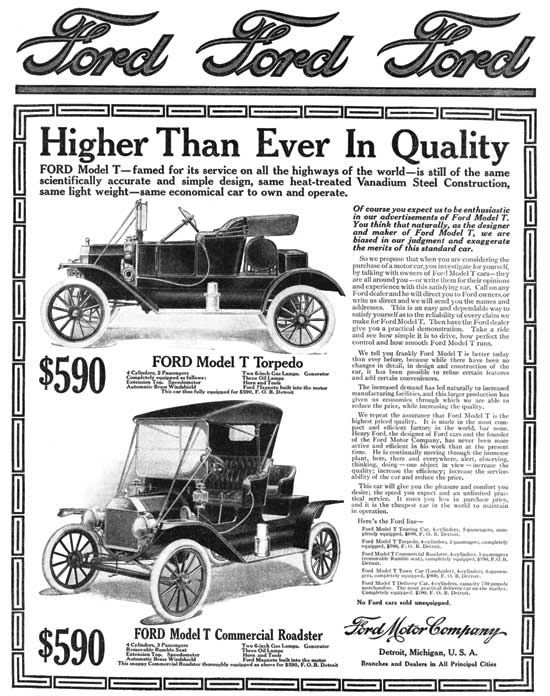

This article and other features about the early automobile can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition: Automobiles in America!

Scion of the famous automobile family, Henry Ford II wrote this Post article in 1976 at the height of the energy crisis. In a time of oil shortages, long gas lines, and worries about U.S. dependence on the oil-producing nations of the Middle East, Ford defends the car and his grandfather’s legacy.

It was just 70 years ago that my grandfather, Henry Ford, wrote a letter to a magazine called The Automobile describing his plans to build 20,000 runabouts the following year. One purpose of the letter was to answer the many skeptics who saw the automobile only as a fad. He wrote: “The assertion has often been made that it would be only a question of a few years before the automobile industry would go the way the bicycle went. I think this is in no way a fair comparison and that the automobile, while it may have been a luxury when first put out, is now one of the absolute necessities of our later-day civilization.”

That letter was written when the car was still something of a curiosity. It had not yet gone into mass production. There was no highway system worthy of the name. The relatively few cars on the roads were mostly in the hands of people of means. There were millions of people in the country who had never seen an automobile, and many towns and villages where none had ever appeared.

But it was in that same year, 1906, that the automobile proved to be the absolute necessity that my grandfather had called it. When the San Francisco earthquake struck, the 200 private automobiles in the city were immediately pressed into service, transporting the injured to hospitals, moving police from one part of the stricken city to another, and helping out in a variety of ways. When it was all over, the San Francisco Chronicle observed: “Men high in official service … say that, but for the auto, it would not have been possible to save even a portion of the city or to take care of the sick or to preserve a semblance of law and order.”

I recall my grandfather’s letter and the role cars played in the San Francisco earthquake only to provide some historical perspective. In order to look at the future of the automobile with any degree of objectivity, I believe you have to remember that the automobile has always had its share of critics. It has them today and it will certainly continue to have them in the future.

In the early part of the century, the critics of the car would see one stalled at the side of the road, laugh at the hapless driver and tell him — in that memorable phrase — to get a horse. Today’s critics are more sophisticated. They assail our automotive culture for the pollution it has brought, for destroying the beauty of the countryside, for congesting the cities, and for a variety of other real and imagined sins too numerous to mention here.

Some of the critics’ charges are true, some are exaggerated, and some are completely false. But the important point is that the automobile is here to stay. Its use will continue to grow, not only in the United States, but in Europe and Asia as well. In the underdeveloped nations of the world, cars and trucks will exert enormous influence in raising the standard of living and providing millions with a cheap, fast, and comfortable means of transportation.

—“A Message from Henry Ford II,”

The Saturday Evening Post, November 1, 1976

Motoring Milestones: How Many of These Facts About the Early Automobile Do You Know?

Automobile Racing

Fousey

October 23, 1909

Motoring milestones and other features about the early automobile can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition: Automobiles in America!

The Inventors

1885

Click it. Edward J. Claghorn of New York receives patent for seat belt.

1887

It still spills all over his shoes. First gas pump is patented by one Sylvanus Freelove Bowser.

1891

Range: 50 miles. Top speed: 20 mph. First successful electric car built in U.S. by William Morrison.

1895

Gasoline firsts. Duryea Motor Wagon Company is earliest company formed to build gas-powered cars. (But Winton claims first auto sale).

1896

Officer, I didn’t see her coming. In the first recorded auto accident, a Duryea Motor Wagon strikes a woman on a bike, breaking her leg. Driver spends night in jail.

1898

Going without the “Flo.” First auto insurance policy is purchased by Dr. Truman Martin of Buffalo, New York. $5,000 in liability coverage costs him $12.25.

Doing the best they can. New York City Police Department uses bicycles to chase speeding motorists.

1901

Rules of the road. Connecticut enacts first speed limit law for motorists — 12 mph in the city and 15 mph on country roads.

1903

A real adventure! Horatio Nelson Jackson and Sewell K. Crocker are first to drive cross country. 64-day trip is made in Winton Touring Car.

What’s in a number? Massachusetts is first state to issue license plate. It’s made of porcelain.

I can see clearly now. Inventor Mary Anderson develops first windshield wiper. Manual device is operated by a handle. Automatic wipers would arrive in 1917.

Oldsmobile advertisement originally appeared in the Post on May 5, 1906

1904

Pull over! First paper speeding ticket is issued in Dayton, Ohio, to Harry Myers for going 12 mph in a 5 mph zone.

Pull over, part deux. U.S. surpasses France in car production.

1905

Temptation for speedsters. H.H. Buffum produces first American V8.

Dirty rags and all. First purpose-built U.S. gas station is recorded in St. Louis.

1909

POTUS gets a lift. The first official White House car is a 1909 White Steamer, ordered by President Taft, over congressional objections about cost and safety.

Ahead of her time. 22-year-old Alice Ramsey is first woman to drive cross country. Trip is made in Maxwell DA touring car and takes 59 days.

The Innovators

Birth of a classic. The first running of the Indy 500. Winner Ray Harroun averages 74.6 mph.

Watch out behind you! The first rearview mirror is used by Harroun in Indy 500. (Other drivers placed their mechanic in the backseat to keep an eye out for cars coming from behind.)

Model-T

1913

Chevrolet makes its marque. The iconic bow-tie emblem appears for the first time on 1914 models.

1914

Hard bodies. Dodge introduces first car body made entirely of steel.

Cadillac produces its signature V8. Known as the L-head, the engine is first mass-produced, water-cooled V8.

It’s a machine, but you have to obey it anyway. Cleveland installs first electric traffic light.

1915

Noise ordinance to follow. The first car to get the horn button in the center of the steering wheel is the Scripps-Booth Model C. In another first, the car sports electric door latches.

Now that’s power! Packard’s Twin-Six is first production car to offer a V12. The car, used in Italy during WWI, would later inspire Enzo Ferrari to design a V12 of his own.

Robert Robinson

January 11, 1913

1916

Federal Aid Road Act. President Wilson signs law giving federal aid for state highway costs.

Ford leads the way. As prices drop and production surges on the Model T, Ford captures 55 percent of the auto market. The record has never been beaten.

1918

Stop, go, and huh? First tri-color stoplight is installed. In Detroit, of course.

Cars for All

1921

Design fails to include arches. The first drive-in restaurant in the U.S., J.G. Kirby and Reuben W. Jackson’s Pig Stand, opens in Dallas.

No umbrella? No problem. Hudson introduces the Essex Coach, the first affordable enclosed sedan, marking the beginning of a shift away from open vehicles. By the end of the decade, nearly 90 percent of all cars feature a closed carriage.

1922

Huge difference in stopping power. The Duesenberg is first to offer four-wheel hydraulic brakes.

Finally, a car for the whole family. The first production station wagon is offered by Star, a division of Durant Motors.

They didn’t reckon on Howard Stern. The radio is offered as an accessory for the first time.

1925

Sleepover date! First motel opens in San Luis Obispo, California.

Dogs and kids in the back. The first factory-assembled pickup truck is based on the Model T, but with rear cargo box. It sells for $281.

Coles Phillips

September 23, 1922

1926

Easy turning. Pierce-Arrow is first to be outfitted with power steering.

1927

15 million sold. The Model T, by the end of its run, hits a sales milestone.

New kid in town. Ford replaces the Model T with its (second) Model A, powered by a four-cylinder 40 hp motor. The car sports innovations such as safety-glass windshield, roll-up side windows, and three-speed transmission.

1928

Lincoln Highway completed. First road to span America, running from New York to San Francisco.

Chevrolet advertisement originally appeared in the Post on August 3, 1929

The Classic Era

1930

Power surge! Cadillac 452 series is first production V16.

Hey! Slow down! There is still no speed limit in 12 states.

Whiz kid. Billy Arnold crosses 100 mph barrier at Indy 500: average speed 100.448 mph.

Anything for the record books. Charles Creighton and James Hargis drive roundtrip from New York to Los Angeles using only reverse gear. The trip, in a Ford Roadster, takes 42 days.

1932

Bigger is better! Ford introduces its famous flathead motor. The V8 becomes an option in the Model B and 18. Later that year it becomes an option in Ford trucks.

Moonlit Car Ride, Eugene Iverd, January 7, 1933

1934

No such thing as bad publicity. Bank robbers Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrows endorse the 1934 Ford Model 730 Deluxe Sedan: “I have drove Fords exclusively when I could get away with one. It has got every other car skinned, and even if my business hasn’t been strictly legal it don’t hurt anything to tell you what a fine car you got in the V-8.” Ford responds with thank-you note.

1935

The original one-armed bandits. The first parking meters go into service in Oklahoma City.

Strength in numbers. United Auto Workers union is formed.

The hard part is remembering to switch them off. Flashing turn signals introduced. (They become standard on Buicks in 1938.)

1936

Rig Leader. Ford is tops in truck sales with 3 million units sold.

1937

Song to follow. Route 66 completed.

1939

Look ma, no hands! GM introduces first fully automatic transmission, the Hydra-Matic Drive, in its 1940 Oldsmobile models.

Henry Ford on Abolishing Poverty

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947), an entrepreneur in the automobile industry, wrote this article at the beginning of the Great Depression. As we debate how to deal with recession during a time when government is increasingly responsible for alleviating poverty, we find it interesting that Henry Ford argued how business can abolish it.

![]() Read “Toward Abolishing Poverty,” by Henry Ford and Samuel Crowther. Published August 16, 1930.

Read “Toward Abolishing Poverty,” by Henry Ford and Samuel Crowther. Published August 16, 1930.