When Charlton Heston Left the Party

Although the astronaut George Taylor lacked the biblical scope of Charlton Heston’s prior roles, audiences may have noted that the philosophical commentary of Planet of the Apes was somewhat aligned with the actor’s canon when the film was released 50 years ago. Heston played some of cinema’s most epic characters — Moses, Judah Ben-Hur, Michaelangelo — before wrangling with primates in the sci-fi classic.

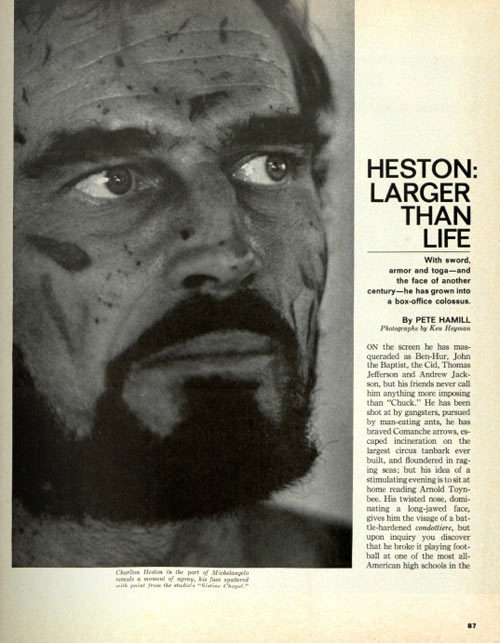

For Heston, acting was serious business. In the Post’s 1965 profile, “Heston: Larger Than Life,” the actor discusses his tendency to wear a toga or chainmail around his Hollywood home while blasting the score for a current movie. At the time, this was George Stevens’ The Greatest Story Ever Told. His strict diet and exercise routine, when considered alongside Heston’s self-inflicted isolation, made it easy to imagine him in the role of John the Baptist. Other actors considered “his prodigious work habits to be feats of enterprise so above and beyond the call of duty as to border on betrayal.”

Heston believed actors bore a more noble responsibility than that of research and interpretation, though. He explained his participation in the 1963 March on Washington, an unpopular decision to his older cohorts: “That march, which was an example of peaceful, lawful civil demonstration, was a responsible act. It was a democratic process, in a way, and if you believe in democracy, then you have to believe in the way it works. As for Hollywood, hell, this is no longer the bad old days.”

In the “bad old days” of Hollywood, as Heston bemoaned, studios wielded extraordinary power over their stars’ lives. The larger-than-life player would not be silenced, however, as he moved increasingly into the political sphere throughout the later century. Although Heston had started as a Democrat, he veered right for Nixon’s 1972 election and never looked back. Before his death in 2008, Heston served as the president of the National Rifle Association and spoke often of the “culture wars” of the American Left.

Heston wrote fondly about his and Reagan’s 1960 studio negotiations — for healthcare and residual payments — in National Review in 2004. Both actors had started their careers as liberal Democrats. Reagan famously said “I didn’t leave the Democratic Party. The party left me,” and he may as well have spoken for both of them. Heston was driven out, primarily, by the Democrats’ softened anti-communist stance as well as calls for affirmative action. He believed the party was giving in to a new whiny, entitled, multicultural block with whom he couldn’t fit.

As Steven J. Ross points out in Hollywood Left and Right, Heston’s most political films, like Planet of the Apes, “reflect his own complicated political sensibilities. Although the ideological messages of the films can be read as left-liberal, the highly individualistic solutions advanced by Heston’s characters prove far more conservative.”

In the course of his acting career, Heston’s sweeping, classical style of interpretation was superseded by the cerebral method-acting of leading men like Marlon Brando and Paul Newman. Similarly, in his politics, Heston was a constituent of the old guard resistant to the new ideas of progress hatched in the turbulent sixties. Although he ended up, perhaps, as the primary Republican darling of Hollywood, he always considered himself a Democrat deserted by a radical party.