North Country Girl: Chapter 33 — The End of Childhood

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. This is the last chapter in the series.

Michael Vlasdic’s mother, the German professor, was always obliging; that summer, she taught a full load of classes, leaving Michael’s house delightfully parent-free for hours and hours. I loved Michael. I never wanted to leave his arms. To be with him, I had spent the past six months fretting over my personal monthly calendar — is it safe to have sex this day? The day after? After every “safe” day I was convinced I was pregnant and doomed right up until my trusty body proved otherwise.

Now the 60s made a further encroachment in Duluth: Planned Parenthood came to town. Until then, the only doctor I knew was my pediatrician, Dr. Bergman, who had seen me in my white Carters undies and examined me for pinworm.

The girl grapevine went into full swing. “I heard if you’re sixteen you can get birth control at Planned Parenthood and they don’t tell your parents,” said a wide-eyed Wendi Carlson. I was one of their first customers. I was so desperate to have as much sex as possible with Michael, to be free of the tyranny of the menstrual cycle, that I turned up at their downtown office and bravely asked to see a doctor. I was ushered into the exam room of a very nice woman doctor, another thing I had only seen on TV. I cringed through my first pelvic exam, even though the nice doctor complimented me on my “textbook cervix.” When my legs were back together and on the ground, the doctor handed me a prescription that read “To regulate flow” and told me to come back in a year.

I had drugs and Michael and his empty house and no more worries about being knocked up. It was a fun summer. I tried to be mindful of the time on my work day when I had to punch in at The Bellows at four to make sure that those idiots who showed up for a steak dinner at five would have a fresh crisp salad. But we were insatiable. One afternoon, as I felt Michael poking me in the leg, ready for a third bout, I raised my kiss-swollen face up off the bed and saw to my horror that it was a quarter to four. Michael was pulling me down; of course he didn’t understand why I had to be at The Bellows on time. Unlike everyone else I knew, Michael did not have a summer job. He refused on principle to work for the man. “Who cares if you’re a few minutes late?” he grumbled. “It’s not like you’re doing anything important.”

The real German, I was determined to keep the salads running on time. I threw on my clothes, not bothering to wash. Michael grudgingly offered to walk me the ten minutes down to The Bellows. Walk? I need to go at a quick trot to get there on time.

I was two blocks away from the restaurant, waiting at the corner to cross the busy-for-Duluth Superior Street. Traffic finally slowed as a bus pulled up and stopped. I started to dash across the street, certain Michael was beside me. But he had seen the car behind the bus veer left to go around it. I did not. I felt a bang and landed on the hood of a cab, looking into the horrified face of the driver. The next thing I knew I was on the ground and Michael was standing over me, red-faced and sobbing, as the bus driver and the cab driver both shot out of their vehicles. I assured everyone I was fine, and got up to continue on to work. No one was going to let that happen; I was guided over to the curb by several hands and forced to sit. Soon an ambulance showed up, and even though I was still protesting — who would make the salads and defrost the shrimp? — I was loaded inside. Before they shut me in, I called over Michael, who bent over me for my last words, which were to call The Bellows and explain that I had been hit by a car.

At St. Luke’s Hospital I was X-rayed and palpitated and asked if I knew the name of the president and what day of the week it was. I did, and nothing was broken; when my father showed up (who had called him?) they were ready to release me. I pulled my jeans on over the yellow and purple bruise that covered my left leg from knee to hip, pushed myself off the examination table and fell over. I could not put any weight on that leg.

My father drove me home in silence, then helped me onto the living room couch, the first time he been in the house since the day he left. He stayed until my mother finally bustled in, furious at having been summoned home by some stupid kid thing, and even angrier that my dad got to act the part of the responsible parent. As soon as he was gone, she lit in to me: how in the world does anyone get hit by a car? Couldn’t I see it coming? She was also suspicious of where I had been all that afternoon; it was July, I was not doing homework at Michael’s house.

In a few days I had recovered enough to lean against the big stainless steel sink at The Bellows, peeling shrimp and cracking oysters; and to figure out ways to make love on Michael’s narrow bed without his weight, however slight, on my injured thigh. Michael kissed the bruises, fading into less corpse-like shades, and told me how sorry he was, how he had just been about to warn me when I went teacups over kettles on the hood of the taxi. He did not feel badly enough to go out and look for a job himself; I kept working and kept spending my paycheck on drugs.

Summer ended and that golden age of youth, senior year, started. Saturdays were still reserved for Michael and acid, but every Friday I was with my friends in the White Delight, cruising up and down Duluth, in search of where the action was. Our senior year parties became wilder, more abandoned, with more booze, more drugs, and dozens of kids in various stages of intoxication. We huddled around house-sized bonfires on the lake shore, tossing empties into the flames and laughing hysterically at nothing. We smashed into the Anderson’s basement; the crescendo of “Stairway to Heaven,” still new to our ears, made conversation impossible and unnecessary.

There were a few casualties. Betsy James had a fight with her boyfriend, and took off on his motorcycle; he found her a block away pinned under it, with a broken leg and a large patch of her skin left on the asphalt. Craig Whiteman, one of East’s few greasers, polished off a six-pack of Grain Belt at a party and accepted a dare to break into old lady Congdon’s mansion. No one knew that Dorothy Congdon was a champion skeet shooter who slept with a loaded shotgun beside her.

My band of sisters grew closer together as high school graduation neared. We had forged a sacred bond, at a time when our hearts and souls were soft and malleable, and our feelings strong and blood hot. Our friendship was built on years sharing our teenage loves and disappointments, laughing, drinking, sometimes crying, and always caring deeply. We knew that college and jobs, new lovers and new friends, would soon disrupt the centrifugal force that kept us together, though we vowed not to let that happen.

Michael and I also believed with the fervor of a religion that we were destined to be forever together, the fever dream of first love. But while I had despaired every time my period was half a day late, Michael romanticized the possibility of us having a baby. He longed for an addition to his tiny two-person family and got all misty-eyed listening to Crosby, Stills, and Young’s “Our House.” We shared a dream of a small apartment in Minneapolis, filled with sex and drugs, college textbooks and cats, where we would fall asleep in each others’ arms, but my dream definitely did not include a baby.

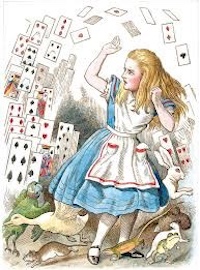

While my heart was sworn to Michael, the rest of me was stirring with other desires. Being safely on the Pill turned a key in my mind, which opened up a new world of sexual possibilities. Emily Dickinson wrote “There is no frigate like a book, To take us miles away,” and for years books had been my only escape from my stolid small town life and boring middle-class family. I could get lost again and again in the exploits of Bilbo Baggins and Gandalf, Arthur and Merlin, Dorothy and Alice, and all those other plucky young heroines. Then I discovered that drugs could shanghai my mind, transport me to different realms. Now I realized that there was another vehicle that could take me away on adventures: my own body.

I started looking at other boys with a hungry curiosity. What would it be like having sex with them? How would they smell, how would they touch me? Would the sex be better or just different? And maybe just different would be exciting enough. According to Time magazine, which still made its weekly appearance in our mailbox, the sexual revolution was in full swing. I was a willing recruit to any revolt. Even my own mother, still pretty at thirty-seven and post-divorce slim, had seduced a former stalwart of the Catholic Church and father of six, and was busy trying to get him to dump his wife and marry her.

The culture, my body and mind, and the nice people at Planned Parenthood were all encouraging me to expand my sexual horizons; the only reason not to was that Michael, my sensitive, moody lover, would be hurt. So I never told him about the others. I was callow and callous, and from a distance of many years, I can see that I was not the adventuress I thought I was — just an asshole.

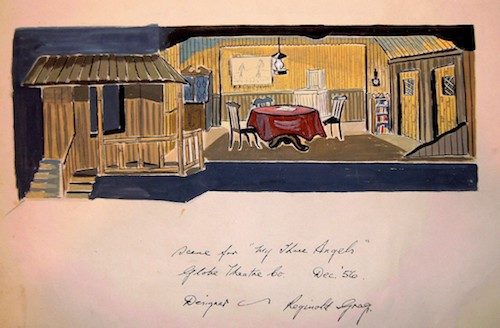

There was Jonathan, who had been making me laugh since seventh grade advanced math. He was a behind-the-scenes stagehand for all our aspirational high school plays, painting flats, adjusting the lights, and cracking up everyone in earshot. The plays our high school put on were ancient chestnuts, chosen for their ability not to offend anyone: starting with “My Three Angels” (misspelled on every poster as “My Three Angles”), about a trio of fugitives from Devil’s Island, through “You Can’t Take It With You,” with its cast of thousands.

That play provided my one chance for glory on the stage. I had been trying out in vain for a part in one of East’s plays since I was a sophomore. Our creepy drama teacher Mr. Canfeld had given every single leading role for the past three years to milquetoast Grace Myers; rumor had it that she let him feel her up. On my ninth audition for him, Mr. Canfeld felt sorry for me, ignored my lack of acting ability, and cast me as Olga, the White Russian countess, who shows up in the final act to deliver her three lines. After our second and closing performance, cast and crew gathered in somebody’s parent-less house for one of the epic theater parties. Drunk and high, Jonathan and I were talking, then giggling like lunatics, then kissing. We locked ourselves in a bathroom so we could take some of our clothes off. As I had hoped, it was different and it was fun, like taking a roller coaster ride together. Miraculously, Jonathan and I became better friends.

One sub-zero Saturday night, Michael Vlasdic and Needle both sick with the flu, Roger and I ended up alone, driving aimlessly around Duluth in search of a party. Sitting next to him on the front seat, like boyfriend and girlfriend, I realized I liked his craggy profile and scooted over a little closer, feeling a pleasurable tingling. When Roger put his arm around me, a bolt shot through my body to where his hand rested on my shoulder; we both felt the electricity through our winter woolens. Without saying a word, Roger steered for Skyline Drive, the favorite parking place for Duluth teens. We stretched out as much as we could in the back seat and committed our double betrayal, he of his friend, me of my soulmate. When we were done, we felt a bit bad and swore it could never happen again. But it did, and it was furtive and secret and thrilling.

I had always had a little crush on handsome, sleepy-eyed Jack France, who showed up occasionally at Open Mind meetings to read his angsty poetry. He was like me, a flitter among groups, a smart athlete who got high. Now I side-eyed him in Mr. Burrows’ class, where he sat alone in the back, gazing out the window. I wondered what it would be like to kiss him.

I found out on a yellow Bluebird bus making its bumpy way back from Telemark, Wisconsin, after a day of spring skiing. Nancy Erman had organized a school ski trip, one of the last hurrahs of our senior year. We skied stripped down to sweaters and blue jeans, luxuriating in the sunshine that was almost warm. There was such joy in the day, in our forever young bodies that we sent hurling recklessly down the slopes, again and again, until the lifts slowed and stopped and it was time to go home. Jack and I had skied together that day, and it didn’t take much wrangling on my part to end up sitting next to him on the tot-sized school bus seat. Jack shook out a package of Lucky Strikes from his pocket and lit a cigarette. Then we kissed. I thought I was the world’s best, most experienced seventeen-year-old kisser; I was knocked for a loop. Jack’s kisses shrunk the entire world down to the two of us, nothing but slightly chapped lips and gentle exploring tongues and the taste and smell of tobacco which reminded me of fall’s burning leaves. On the bus, in parkas and long johns and snow-soaked Levi’s, there was nothing more we could do than kiss, and the kisses were everything.

Jack and I never went any further. For years, every time we ran into each other, Jack and I would end up in dark corners where we shared those deep soulful kisses, sometimes for hours, until he took off one autumn on a solo cross-country bike trip to Seattle, where he leapt off the George Washington Memorial Bridge.

Being with Jonathan, Roger, and Jack was fun, it was sex with no agenda, no strings attached. It wasn’t about love, or negotiating a relationship, or even about my desperate desire to be thought of as pretty and sexy and cool.

I was beginning to regret the plans that Michael and I had made, that we’d go off together to the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis and live happily ever after. I was going to spend my first year in a dorm; he would stay with a friend of his mother’s who had offered him almost free rent and board. Eventually we would find an apartment and move in together. In the pleasant mist of these daydreams, I didn’t think about how we would pay the rent; his mother had no money, I knew neither of my parents would subsidize my living in sin, and Michael had never shown the slightest desire to find a job. I had left the salad and the shrimp at The Bellows behind; my vast restaurant experience got me hired as a waitress at The Flamette, where despite my dropping a full glass pitcher of maple syrup my first day and my inability to carry more than two plates at a time, I was making enough to buy drugs and squirrel away some spending money for college.

East High had no guidance counselors to talk to about universities; the only adult who had spoken to me about college was my grandmother, who offered to pay my tuition if I went to St. Scholastica, a Catholic woman’s school right there in Duluth. No thank you.

I filled out the application for the University of Minnesota, wrote the essay, tore out and filled in a check for $15 from my mother’s checkbook (she had finally gotten her own bank account), and sent the package off to Minneapolis, never doubting that I would get in and never considering applying to any other schools. The housing catalog that came with my acceptance letter featured a brand new, co-ed dorm, the only dorm that allowed 24-hour visitation from the opposite sex — as long as you had your parents’ permission. I checked the box for Middlebrook Hall on my housing form, forged my mom’s name on the permission slip, and fell into a fantasy of unlimited sex with unlimited college boys, with an occasional guest appearance by Michael Vlasdic.

For once the reality matched the daydream. My perky, adorable, All-American college roommate, Nancy Lowe, went back to her suburban home every weekend to work at the local pizza place and have sex with her own boyfriend, leaving me a wonderfully empty dorm room for entertaining. I was sandwiched between boys; at Middlebrook Hall the sexes alternated floors. My new friend Liz Hepper, who I had met in her dorm room closet, where she was chugging a bottle of Southern Comfort, introduced me to a herd of funny, smart boys from her hometown of Rochester, including a pharmacy major who had very good drugs. There were so many boys in my dorm, and they were all so interesting and cute. And out on the huge campus there were 20,000 more, surrounding me in class, eating dinner in the cafeteria, napping or reading or throwing Frisbees on the still-green campus lawns.

Despite all our plans, despite my absent roommate and the 24-hour visitation, despite how much I thought I looked forward to the first time I could sleep with him, entwined and spooned and inhaling his sweet spicy scent, Michael and I never spent a single night in my skinny dorm bed.

Before the first week of college was out, I called Michael and broke up with him, in the worst way possible, over the phone.

There was another important phone call that first month of my freshman year. My mother called to tell me that she was moving to Colorado Springs. She did not tell me that she was moving in pursuit of the ex-Catholic father of six, who had finally left his wife; he had also left Duluth to live on a small ranch in Colorado. I was instructed to come back home that weekend to box up anything I did not want sold or thrown out; my mother and sisters were downsizing from a six-bedroom stately home to a two-bedroom apartment.

I wandered through 101 Hawthorne, most of the rooms already empty of furniture. Almost everything was gone from my old bedroom, where I had spent so many nights tripping, transfixed by the golden glow from the streetlight streaming through the trees. A few summer clothes hung in my closet; I put them in my suitcase, looking forward to catching some boy’s eye in my cute Indian-print sundress in the spring.

I went back down to the TV room, where our bookshelves were, and where two large cardboard boxes sat gaping. “Put what you want to keep in one,” said my mother. I pulled from the shelves the books that had been my youthful frigates: Alice’s Adventures, the Tennile drawings only slightly defaced from Crayolas wielded by my sister Lani. The Wizard of Oz. The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. The Fairy Tales of Hans Christian Anderson, minus “The Little Mermaid” and “The Little Match Girl.” I opened up the books Michael had given me, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings trilogy, each frontispiece signed “I love you” illustrated by his round smiling face. My heart gave a small twist as I stowed them in the moving box. Next came the never-paid-for plays of William Shakespeare, three heavy tomes, The Histories barely cracked. I added The Guide to Minnesota Fauna and Flora, which had been handed to me by the outdoorsy old lesbian who had dragged me around Duluth’s fields and woods. Here was Angelique and the Sultan, with steamy seduction scenes on every page, never returned to Kathy O’Dell. A ragged paperback sci-fi novel, The Blind Spot, that I had read three times in a row, on that trip to Mexico, lacking any other English-language reading material that was not dental-related. And of course the fruit of my junior year with Mr. Burrows, the two volumes of American history and literature, typed out night after night, with my name printed on the spine in gilt letters.

I sealed my cherished books up in a moving box and told my mother that was all I wanted shipped to Colorado. That Christmas break, in my mom’s ticky-tacky Colorado Springs apartment, I sat in the living room, hemmed in by our old furniture: the mahogany dining table for six, the gold and cream French Provincial sofa and matching end tables, and the immense cabinet TV. I opened a cardboard box identified as “Gay’s Books” in black marker. It contained stained Junior League cookbooks, several years of Reader’s Digest Condensed Books, a collection of Harold Robbins paperbacks, a single addendum to the World Book, dated 1960, and a battered Webster’s dictionary. My childhood was gone.