Cartoons: Home Sweet Home

Home: where you are loved the most and act the worst!

Fred Balk

December 28, 1940

December 11, 1943

H. Middlecamp

January 4, 1947

Stan Hunt

December 27, 1947

Shep

January 3, 1948

Stan Hunt

December 28, 1957

Nick Downes

July 1, 1991

Marty Bucella

September 1, 2010

Tom Cheney

June 1, 2015

Working for Liberty

One of the things I’m proudest of about the United States is that we’ve always been a nation of dreamers and strivers. I spend a lot of time in France, and as much as I love it there—its gorgeous countryside, magnificent wines, haute cuisine, haute couture, and all things related to the enjoyment of life—the French do not seem as interested in striving as we are. In recent years, like the rest of Europe, the French are unwilling to let work be the focus of their lives. They want more benefits and time off, longer vacations, earlier retirement, and are willing to give the government whatever power it needs to make that happen. In other words, they’re willing to trade a little of their liberté in exchange for more égalité and joie de vivre.

Remember it was the French who gave us that wonderful statue celebrating liberté in New York Harbor, of the lady holding a torch, the one they so aptly named Liberty Enlightening the World.

Liberty is what America has been all about over the years. Most American families came from somewhere else. What all looked for in the United States has been freedom and independence. A meritocracy where anything is possible—a country where striving, regardless of race, creed, or color could pay off. A land where dreams come true. Is that so wild a dream? President Obama is living proof it isn’t. But the idea of “yes we can” did not start with him. Over the years, American inventors from Benjamin Franklin, Eli Whitney, and Robert Fulton, to Thomas Edison and the Wright Brothers confronted naysayers who told them it simply couldn’t be done. Of course, they proved otherwise, thanks to a combination of inspiration and perspiration—Edison claimed it was mostly perspiration. Thanks to their tireless efforts and vision, they made life better for themselves and everybody else, too.

And we Americans could not only dream, we could build as well. Not only do we create new machines, we make them run.

Today, we hear sophisticated people say that America can’t make what we create anymore, that we have to outsource manufacturing because Americans don’t want to get our fingers dirty. When I hear that statement, it makes me sad, even angry. And I don’t believe it for a minute. Given half a break and a level playing field, American workers today are still the most productive and efficient in the world. While far from perfect, we are still the nation of dreamers and strivers. And one thing we still dream of and strive for is freedom, not just for a chosen few, but for everyone in America.

Once when the Mormon Tabernacle Choir was singing at Lincoln Center, they asked me to write a patriotic poem. The choir hummed “My Country ’Tis of Thee” in the background. Here’s what I wrote:

America, land of the free,

My home sweet home of liberty, of thee I sing;

Let freedom ring for everyone in America:

Freedom from want, freedom from fear,

Freedom to speak, freedom to hear.

And when we bow our heads to pray,

To worship God in our own way,

I have a dream, may it come true

For everyone in America.

An Ordinary House

For many of us the home that’s fondest in our hearts is one we remember from childhood. For me it was the first actual house I ever lived in—a rental the family moved into when my father, a textile salesman, was transferred to Baltimore from New York. Up until then, we’d been living in an apartment in the Bronx, also a rental. I’m not sure co-ops and condos even existed then. If they did, Mary Ann and I sure didn’t know about them.

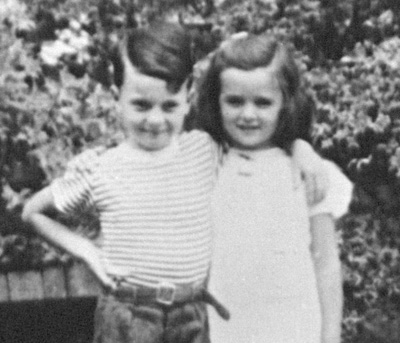

Mary Ann is my sister. We were both 8 years old at the time, but we weren’t twins. We were what everybody called “Irish Twins,” born in the same year; I in January, and she in December. My folks talked up this move to Baltimore, telling us we’d be living in a place with a lawn. This seemed pretty exotic to us, and we were really looking forward to that. On the day we moved in, while the moving men were unloading furniture from the van, Mom looked out an upstairs window and saw the two of us lying on our backs on the little postage stamp of a lawn, looking up at the sky. But the front lawn didn’t look small to us. It looked like the country. Imagine our delight to find out the place had a backyard, too. Also small, the backyard provided a little more privacy and enough room for playing tag and hide-and-seek with neighborhood kids. We’d bounce a rubber ball off the steps, use a bamboo clothesline stick as a pole vault, and hide Easter eggs when that season came. Big enough for games and growing a victory garden—mostly tomatoes, pumpkins, and radishes, as I recall. And sure enough, victory did come, didn’t it? We did win World War II. Around that time, our baby brother was born, and sharing his growing up would be a big part of our life story, too. While there would be other houses we’d call home, our first home on Edgewood Road is the one that always comes to mind.

The house had a big front porch with a swing on it. When it rained, we’d hang out there with neighborhood kids, tell each other movies we’d been to, scene by scene, and sing rounds like “Row, Row, Row Your Boat.” That porch was where Mr. Shapiro used to leave the dozen or so copies of The Saturday Evening Post that I used to deliver to neighbors. I remember laughing a lot at the cartoons, and sometimes those Norman Rockwell covers were funny, too. I never thought I’d be in The Saturday Evening Post. Later, I’d also delivered The Baltimore Sun. All those things I associate with the outside of that particular house on Edgewood Road.

Inside, of course, was the kitchen. I remember Mom putting newspapers on the kitchen linoleum and spraying us both with calamine lotion, head to toe with a flit gun, when we accidentally rolled around in some poison ivy. In that room, I also remember the more pleasing aroma of dinner being cooked. They say smell is the strongest sense memory. I can still smell mushrooms being sautéed and the aroma of split pea soup simmering on the stovetop. Whatever the dinner was, the family would always eat it every night in the dining room when Dad was home. Afterwards, Mary Ann and I would help with the dishes: I’d wash, and she’d dry, or vice versa. There was a lot of singing going on, too.

In the living room was the piano, which always got a workout. Mom played “That Old Silver Moon Shining Down Through the Trees.” Both Mary Ann and I were taking piano lessons from Miss Matilda Dietch so there was much practicing. Usually we played a duet; “Voices of Spring” is one I remember as well as “Tales from the Vienna Woods.” When the piano wasn’t playing, the radio was. No TV of course in those days. But to this day I can tell you who sponsored which shows: The Shadow was Blue Coal; Jack Benny, Jell-O; and The Lone Ranger, Silver Cup Bread.

The expression “Home Sweet Home,” to me, is the memory of voices and faces in that place on Thanksgiving and Christmas, of friends and relatives—grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, and a little dog named Inky.

It’s not the rooms of that house I think of so much as what went on there. It’s always the people; the singing, laughing, and joking—and occasionally quarreling and crying. Quite often, actually, come to think of it. You go back and look at a house all these years later, and it seems so different now, much smaller than you remember. And you realize that if it’s still there at all, it has to be basically what it was. It’s us who have changed. It’s not the brick and mortar, the shape, or size that matters. It’s the people; it’s the life. Old Edgar Guest had it right when he wrote, “It takes a heap o’ livin’ in a house t’ make it home.”