The Hollywood Murder That Made States Take Stalking Seriously

Crime in Hollywood isn’t much different than crime in any other town. That’s an aesthetic communicated in the work of writers like Raymond Chandler and James Ellroy that expose the dark underbelly under the bright lights. However, crimes in Hollywood often seem magnified in the media, particularly when they involve the famous. Sometimes, the cases are salacious and the outcomes ruin careers. When the cases involve stalking or violence, even murder, they sometimes generate enough attention to instigate positive change, despite the horror of the crime itself. Our increased awareness of stalking today forces institutions to make real change, like the decision by Google this week to pull several potentially dangerous “people-tracking Android apps” from its Play Store. 30 years ago, the 1989 slaying of Rebecca Schaeffer drew attention to the issue of stalking; as in the near-fatal stabbing of Theresa Saldana in 1982, the perpetrator was an obsessed fan who used public records to track his target. The fallout of the case and trial would strengthen privacy laws and put a spotlight on the danger associated with stalking.

Schaeffer was born in Oregon and began modelling in her teens. By 1984, she had moved to New York City where she attended Professional Children’s School while she worked. Near the end of that year, she began a six-month run on One Life to Live. She spent some time pursuing work in Japan before coming back to the States; an appearance on the cover of Seventeen led to her casting in My Sister Sam, a CBS sitcom vehicle for former Mork & Mindy star Pam Dawber. Schaeffer played Patti, the younger sister of Dawber’s Sam. A hit out of the gate, My Sister Sam had a strong first season but was cancelled in the second when ratings dropped. Coming out of the show, Schaeffer booked work in a few television and theatrical films.

Arizona native Robert John Bardo had a troubled history. A victim of abuse from a family with a history of mental illness, Bardo himself was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. He previously stalked child activist and television performer Samantha Smith; Smith gained fame in 1982 when, at age 10, she wrote a letter to Yuri Andropov on the question of peace, and the leader invited her to visit the Soviet Union. Her popularity led to her casting in the short-live Robert Wagner series Lime Street; unfortunately, Smith and her father died in a plane crash in 1985. Bardo’s obsessions shifted, and eventually settled on Schaeffer through her role on My Sister Sam.

Theresa Saldana played herself in the 1984 film about her attack, Victim for Victims: The Theresa Saldana Story.

Bardo wrote letters to Schaeffer and even attempted to enter the set of the show. He turned to a detective agency, and they acquired the actress’s home address for Bardo from the California Department of Motor Vehicles. Bardo copied the tactic used by Arthur Richard Jackson; in 1982, Jackson hired a private investigator to get information on actress Theresa Saldana, then best-known for her role in Raging Bull. Jackson acquired the phone number of Saldana’s mother and called her claiming to be Bull director Martin Scorsese’s assistant; he said he needed her daughter’s address so that he could reach her about a film opportunity in Europe. Jackson used the address to ambush Saldana, stabbing her ten times. Remarkably, Saldana lived, though she spent four months in the hospital. After the ordeal, she founded Victims for Victims, an organization that would support victims and lobby for stronger laws.

In 1989, Bardo watched the film Scenes from the Class Struggle in Beverly Hills. Schaeffer’s love scene in that film sent Bardo into a rage. Having obtained the address from the detective agency, Bardo went to Los Angeles. Upon his first visit to Schaeffer’s home, she opened the door and spoke to him; he showed her a previous letter and autograph he’d received from her, and she ended the conversation by asking him not to return. He returned an hour later. When Schaeffer opened the door, he shot her in the chest. A neighbor called emergency services, but Schaeffer died shortly after she arrives at Cedars-Sinai Hospital. Apprehended in Tucson after behaving erratically in public, Bardo confessed. He was sentenced to life in prison without parole.

Earlier this year, ABC’s 20/20 revisited the Rebecca Schaeffer case. (Uploaded to YouTube by ABC News)

The case caught nationwide attention. In the aftermath, the story of how Bardo got the address and its roots in the Saldana case outraged many. Victims for Victims and other organizations joined in a wide-ranging effort to get the laws amended in California. By 1990, California passed the first stalking law; today, all 50 states have a version of the law on the books. The Driver’s Privacy Protection Act of 1994 prohibits the DMV from giving out the addresses of private citizens; the creation and passage of the Act is directly attributed to Saldana and Schaeffer’s stories, as well as harassment directed against abortion providers and patients. The LAPD also has a special unit, the Threat Management Unit, that deals with reports of obsessed fans and stalking; victims in felony stalking cases can now also obtain restraining orders that last up to 10 years.

Stalking hasn’t gone away, particularly in the case of celebrities. Sandra Bullock, Harry Styles, Selena Gomez, and others have dealt with the issue in recent years. Fortunately, there is now greater awareness of the seriousness inherent in the topic and a much greater set of tools for law enforcement to use. Earlier this week, Google’s action against apps that people were using to spy on their “romantic partners,” while tracking their movements, is a positive step, but a reminder that society should remain vigilant. Rebecca Schaeffer’s promising life and career may have been cut short, but there’s a tiny ray of positivity in the notion that many more people have been protected, and possibly saved, as a result of her passing.

Featured Image: Rebecca Schaeffer (Wikimedia Commons)

Pen Pals with the Killer of Kitty Genovese

Years later, Winston Moseley would describe it as a robbery that went wrong.

He claimed he’d never seen Kitty Genovese before, and he had no intention of harming her.

But when she saw him on the morning of March 13, 1964, in her New York neighborhood, she started to run away. Moseley said, “I kind of lost my head.” He pursued her and then stabbed her twice. Crying for help, she collapsed to the ground. A neighbor, hearing her cries, shouted out his window, demanding to know what was going on. Moseley ran away, and the neighbor saw Genovese rise and walk into her apartment building. Once inside, she collapsed on the entryway floor.

After getting away from the scene of the crime, Moseley slowed and thought. And then he went back to his victim and killed her. The murder became infamous for the number of witnesses to the crime who did nothing to help her (although many of the facts in the New York Times story that appeared two weeks after her murder were later questioned and found to be grossly exaggerated). Still, 55 years later, the murder is remembered as an example of what can go horribly wrong when everyone thinks, “I shouldn’t get involved.”

One woman who got involved — albeit inadvertently, and years later — was Melody McCloud. Moseley’s account of his murder of Genovese is detailed in a series of letters he wrote to McCloud, then a pre-med student at Boston University.

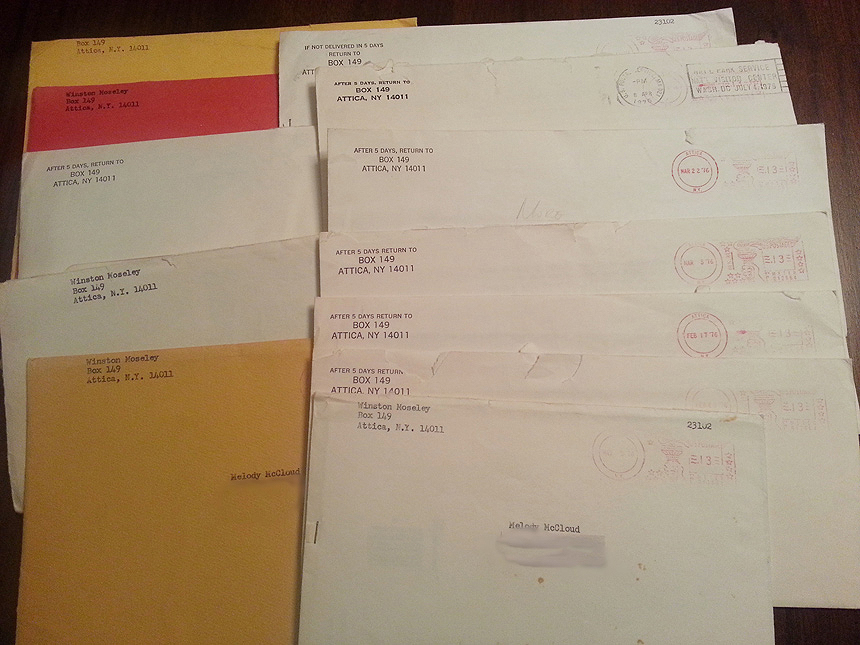

While still in school, she’d been involved in a prison ministry, sharing the message of forgiveness and redemption with prisoners. Later, in 1975, she saw a television news story about Moseley, in which he was identified as “Inmate Liaison to Attica Correctional Facility.” He told the reporter he was working to improve conditions for prisoners following Attica’s deadly riot in 1971. Although Moseley was a total stranger, McCloud wrote him a letter of encouragement in his liaison work. The next month, she received a letter back from him, and a correspondence began.

Over the next five months, he wrote twelve letters. Some included poems or cards. It was in his third letter that he wanted her to know about his conviction “right from the start so you can decide whether or not the facts…are going to make any difference to you.” He told her that he was the murderer of Kitty Genovese in 1964 and once escaped from custody.

The name “Genovese” sounded familiar. She recalled that the case had been a big deal at the time. She looked up details in the library and discovered that Moseley had confessed to murdering two other women — Barbara Kralik and Annie May Johnson — and was accused of forty robberies and various assaults and rapes.

McCloud was stunned by what she read. She recalls thinking, “What’s a nice girl like me doing in a story like this?”

She wrote back to Moseley about what she’d learned. He responded to her questions about Kralik. He also described, at length, his mental state the night of Genovese’s murder.

He’d felt defeated by his two divorces and separation from his children. His parents, to whom he was very close, had been having serious problems for years. He wrote that it created “a psychological disturbance for me.”

After attacking Kitty and running away, he wrote, “what I went back for was some vague notion of taking her to a hospital.” After putting on a wide-brimmed hat to avoid recognition, he returned to her apartment building. He found Kitty on the floor of her building’s entry. When she saw him, he claimed, she began using abusive, racist language. In his letters, he wrote “I stopped being human.” Overcome with hatred, he attacked her again, stabbing her repeatedly while she called for help.

Moseley wrote that he didn’t feel hurried because he knew no one would come, no one would interfere.

“I didn’t want to get involved,” was reported to be a common excuse of the witnesses. The incident gave rise to a new, sinister, phenomenon: “bystander syndrome,” a symptom of urban life in which people abandoned their sense of responsibility and human connection.

In response, residents of New York City began neighborhood watch patrols. And the city established the first 911 system for calling the police.

Later investigation contradicted the claim of 38 inactive witnesses. Moseley said the number had been exaggerated to make the crime sound worse. It was certainly bad enough, becoming the most infamous murder in a year that saw 630 murders in New York. But this crime magnified New Yorkers’ fear that they couldn’t count on others for help in an emergency.

Less than a week after murdering Genovese, Moseley was captured while burgling a house. He confessed to the murders of Genovese, Kralik, and Johnson.

After learning the details about Moseley’s past, McCloud continued to write, but not as often. She began easing away from the correspondence, telling him she was too busy. “How can you be so busy you can’t write?” he challenged in his next letter. He was angry, she says, and he added threateningly, “you better be careful!” In a later letter, he apologized for his anger.

Their correspondence ended in May of 1976.

Moseley remained in prison until his death in 2016. During his 52 years in prison, he had applied for, and was denied, parole 18 times.

While Moseley lived, McCloud, who is now an obstetrician-gynecologist and author who lives in Atlanta, Georgia, did nothing with the letters.

Today, her collection of letters offers a unique insight into the mind of a serial killer, made even more valuable for their candor. “I was not anyone who could really help him,” she says. “I was just a kid, basically. So I don’t feel he had anything to gain by lying to me about his psychological state.”

For 43 years, Dr. McCloud has held onto these letters, not wishing to publicize them while Moseley lived. This year marks the 55th anniversary of Genovese’s death. It’s time, she says, to share their contents.

Feature image credit: Courtesy Dr. Melody McCloud. Used with permission.