Secretariat Speaks: “A Century of Derbies”

Being the true thoughts and reflections of Secretariat himself, as ably noted and transcribed by our best horse intereviewer, Starkey Flythe, Esquire.

Originally published in 1974.

The first week in May. The jockey’s silks are as bright as a bridegroom’s cravat. We are rubbed to the patina of antique Georgian furniture. Thirteen of us. There is the soft smell of leather and light tweed, earth that a hundred years of horses have kicked up and a hundred years of juleps in silver stirrup cups have wet down. And rising, ever so faintly, above the crowd, over the salt tears that edge out of eyes when “My Old Kentucky Home” blares, a whiff of roses. (I just gave you that hit of purple prose to dissociate myself from those other talking equi and muli, Mr. Ed and Francis.)

Anybody can run in it. At least if they’re registered by the Jockey Club. And there’s a story about a horse from out West who was asked not to, but whose owner insisted, until the nag was entered only to refuse to go into the starting gate, but once in with the help of all the King’s men, refused to go out, and finally out with the same aid, ran backwards. But “anybody” rarely wins it. Of the ninety-nine starts, forty-three post-time favorites have won.

IT is the ninth race in a day of ten. Post time is 5:30. And for the moment, Churchill Downs is the center of the universe. For racing? No, not just for racing. For radiance. The horse that wins will wear, not just as long as his head is above the turf — but forever—a crown of glory. A brass name plate on his turn-out bridle. A plaque on his stall door. He will become a living moment in the big and noble hearts of Thoroughbreds. He will never be referred to again as a stakes horse, normally a compliment opposed to being called a “plater”— one who competes for trophies. He—or in one case, she—will always be a Derby winner.

The money is $125,000 to which are added nomination fees, entry fees ($2,500) and starting fees ($1,500). The mutuel pool my year was $3,284,962. The total bet, over $6 million (a record). The value to the winner, $155,050. Which isn’t bad for 1:59.4. Which was a record for the track. Which, noted the Daily Racing Form, was fast. But nothing compared to me. I ran faster the last quarter than the first. Went by the stands last first. And first last. Which is when it counts.

Elation. True elation. It is a rare experience. Mares have said when they’ve dropped a foal and seen it, wet from birth, struggling to its feet awkward as a chapped-lip whistle—and seen that its points were those of a champion—straight and flawless legs, trim and tight knees and ankles, and that the colt would race and someday people would know his name—then they have experienced elation.

Elation came to me-more I think at the Derby than at any other race. I didn’t mean to be a ham, though Mrs. Tweedy says I am—”He pricks up his ears and gazes off nobly into the distance when he hears cameras clicking”—what do they expect of you when they take a million pictures of you?— one photographer even has a recording of mares in heat he plays to get our attention—but the grandstands seemed the place to lead. Ron Turcotte was no more than a fly or a gnat on my back when he struck me with his whip leaving the far turn. Then he switched it to his left hand. Flashed it. It seemed my lungs swelled, like water wings, lifting me into the ether—I never touched the ground again —the rest of the world seemed to have wound down to a snail race. I could hear the rows of men, see their arms high, know that it was me they were calling—almost to come back—but I had gone beyond them and could never go back. My heart was a boiler of blood. It seemed to me it might explode, but I could not stop. Then something outside of me took over and I was not merely me anymore. I was Pegasus, flat and lean, hurled against the sky. There was no resistance. The elements lay docile at my feet. Until I had passed; then they shoved me. A pair of wings crossed the finish line. I was already in the winner’s circle and Mrs. Tweedy was leading me out to the roses.

I could remember Sham, the horse I competed with who beat me in the Wood Memorial, and who came in second at the Derby, his mouth the color of roses too. Only it was blood. When we were being loaded into the starting gate. Twice a Prince—he ran next to last—perhaps he knew he was going to—refused to enter his stall. He reared up and threw his jockey. Shoes clanged against the metal of the stall divider. Sham’s head hit the gate, drawing blood, nearly knocking out his front teeth. Ron, smart as the horsefly he is, hadn’t loaded me in yet and turned me away from the clatter. Somebody got Twice a Prince out of the gate and soothed him. They got his jockey back up and all of us were in our stalls and off.

My hood is checkered—the colors of home—The Meadow-blue, white—it is like the flags at a Grand Prix-and on the backstretch I could see the blood flying from Sham’s mouth and right up to the wire I knew he was there, running fine, fast, rising over the pain and fear he felt. It would have been his race—any year but this one. Two who in any company would shine were this year against each other. Still, I could never have known myself against any but the best. Sham is the best. Races are never between the quick and the dead. They are between the quick and the quick.

There’s another horse I have to name, too. My stable mate, Riva Ridge. Riva is a dark bay—almost mahogany with sable legs and mane, a shortness of grace and going; he now stands at stud across the lane, a paddock away from me, at Claiborne Farm. I see him, silhouetted, motion even standing still, and there has been, at times, envy between us. When he won the Derby—the ninety-eighth running—he was the center of attraction. When I came along, there was trouble. People used to come see me in my stall, passing Riva Ridge. And he knew it and would turn his backside right up to the stall door, letting them have a taste of their own fickleness.

Riva was the horse that first brought glory to The Meadow and made us all celebrities. And when Christopher Chenery, who founded The Meadow and gave us all our chance and had always wanted to have a Derby winner, was so ill and down in bed, Riva won and we don’t know, but we think Mr. Chenery understood, sick as he was, that he had a winner, and he went out happy.

Photo by Tony Leonard.

Sometimes I think about the hardships of racing. About the cold morning workouts. About the other horses, the sting of the earth as it flies up and hits your belly, the closeness of the other horses, their fear and your fear, the tricks unscrupulous jockeys sometimes play on you, the animosity among trainers in the barns and stables at racetracks, the way we know we are going to be run (instead of the usual four quarts of oats for lunch, there’s half a quart, and the hay outside the stall is taken away), the way they—grooms, trainers, hands—try to make you relax, and how it never quite works. When they are nervous, you are nervous. “Horses ain’t like humans,” my friend and groom of last year, Eddie Sweat, said. (And we can thank the great Four- Legged One above for that.) Eddie says, “They have a mind of their own and you never can tell what they’re going to do. You think you have them settled down, but something happens, and it might bother them.”

Well, we’re hyperopic (farsighted). And we can’t see things close up unless our noses are practically touching them. Nor can we see directly in front of us, but to either side, behind, and to some extent above and below.

Stick your finger out in front of you. Now blink your left eye. Then your right. Fast. The finger seems to jump. Your eyes are an inch apart. Ours are six. Think how inanimate objects spring out at us. Then think that our ancestors knew running away was their only defense. Far-sightedness shows us the enemy at a distance. Farsightedness creates time for head starts.

So against this heritage—not to mention the Arabians bred with English mares 200 years ago— the registered Thoroughbreds in America are descended from three sires: the Byerly Turk, the Godolphin Barb and the Darley Arabian—we are expected to perform in a world where people are our only friends, where stall walls are too high to enable us to get aquanted with any horses. Throughbred is a distinct breed of horse, just like Morgan, Hambletonian, Percheron or Hackney. We have a dished or straight profile, a long, slender neck, sloping shoulders, fairly short back. The width of brisket—the space between our forelegs—is large, making room for the great heart of a Thoroughbred and the powerful lungs. Our muscles are flat and stringy, mane and tail thin and fine, veins violin strings, skin so thin we suffer terribly from flies and hot weather. We are high-spirited, but rarely mean or stubborn; ruined by rough treatment and easily gentled as a foal by kindness. Courage and quickness, spirit and delicacy mark us—no horse in the world can stay with us on the track; none can outjump us in the field. And we all have the same birthday, January first. At a year we are considered to be seven. At three, we are one and twenty and our lives—in some stallions’ cases—are paved with woo.

People say Ron Turcotte and I have our own style, that we break from the gate and then drop back; that’s a nice thought. The competition isn’t a bunch of drays, though, or the race an amateur version of The Iceman Cometh. They’re the fastest horses in the world and they’ve been trained all their lives for this day.

We have our own starting gate at The Meadow—and at Belmont, where I trained. So we’ll know how to break. So we won’t be afraid. Mrs. Tweedy thought of that and discussed it with Lucien Laurin, my trainer. (I love it when people discuss around us, their voices are quiet and soft—they don’t want to upset us—vexation never won a race.) Lucien said he thought it was a good idea.

I like Penny Tweedy. She said the first time she saw me, “Wow!” And it stuck. “The Wow Colt.” “The Wow Horse.” She’s sort of like me. Well bred (old Southern family-The Meadow belonged to her father’s people before the War between the States), well educated (Smith, Columbia University-business administration), she knows what she’s doing, and she does what she knows, and pretty (people cheer when they see her—and pretty is as pretty does so she got a public relations firm to handle the dishing out of me as a public figure), and, heaven forgive me, well fed.

Most stallions do fairly well on twelve quarts of oats a day. I like sixteen. And I nibble hay while the sun shines, and after it goes down, I have a special supper. A sort of mash of oats fortified with vitamins and minerals plus carrots and “sweet feed”—molasses-coated grain. Some horses won’t eat after a big race. But it just works up my appetite. I hate to use the word tub, but bucket doesn’t really size it up. One of my grooms describes me as a “neat eater.” “He has a sip of water every now and then between his mash. Then he picks up any stray buds on the floor and varies everything with a few wisps of hay. But, lordy, the amount.”

Well, consider my size. Twelve hundred pounds. Supported on legs less than yours. Like a bumblebee or a C-47 (from an engineer’s point of view), I shouldn’t be able to fly. And I’m still growing. My girth is seventy-five and three-fourths inches—about an inch more than Man 0’ War (who was also called Big Red) and I have to have a custom-made girth to hold my saddle. I can cover twenty-five feet in a single stride. You can see how that would eat up the Derby track, one and a quarter miles.

Ron always says, “I like to let him find his feet. Then he gives me his speed when I chirp to him.” Sometimes, the “chirping” gets lost in the noise of the race and he calls out with the crop. I don’t like it. I never have. I remember when he first used the whip. 1972. It scared the fodder out of me. I ducked into another horse and our number was taken down for a foul. I had begun my career in racing at Aqueduct—Fourth of July—appropriate date for the “horse of the century”-when another horse bumped into me at the gate and knocked me out of my direction. “If he hadn’t been such a strong horse, he’d have gone down,” the jockey said. Still, I got myself together and finished fourth. Since that day I’ve never been out of the money. Unbeaten—a good word in most sports—never really applies in racing. Man 0’ War and Citation were beaten. I’ve been beaten. But finished first in eleven out of fourteen races. How can we, after all—mute according to our masters—say we feel bad and want to stay in the barn, that we are under the weather or the weather is under us. At the Wood Memorial at Aqueduct in April, a few days before the Derby, I came in behind Angle Light and Sham. For the drama of the Derby, I suppose, I couldn’t have done better had I tried. Many sportswriters and racing experts said I’d blown it. Of course the odds are the real sportswriters. And they remained $1.50 to $1.00. Sham’s were $2.50 to $1.00 and Angle Light’s were the same as mine. Angle Light finished tenth and Sham, of course, second. So from the gate we are fighting. Even when

we drop back. Strategic withdrawal you could call it. But the more you spot the competition, the farther you’ve got to go to catch up. Then you have to pass. And keep up. They said at the Derby when we swung around the outside, passing horses until only Sham was in front, we could never keep up such a rally to the finish. Just before the midstretch, I caught him—perhaps it was the sting of the whip I feel I’d have got him anyway—and beat him by two and one-half lengths for the fastest Derby ever.

I often think green and while are the colors of the South. They know how to hang deep green blinds on spanking white walls, or how to plant a magnolia against a snowy column. That’s the look I get saddling up in the paddock. Thousands of tulips blooming just for us. The whole Derby is like a flying flag. Patriotic, colorful, wild in the bluegrass breeze.

The moment the jockeys touch our backs—one of my friends said they look like squabs turned up in a Christmas pie with their little rumps—we start for the track where the outrider in a red jacket, usually on an Appaloosa, meets us and leads us out for the post parade and the warm-up. Like athletes—why say “like” athletes, we are athletes—we have to warm up our muscles.

I love the far side of the track—it seems almost a far country. Even on Derby day when the inside of the track is filled with bodies—mostly young people with their shirts off for the warm May sun so that the track seems to be some giant public pool—quite a different sight from the boxes on the other side which cost $1,600 for the day—the noises hang in the air, a distant fantasy, a conglomeration of the great ocean liner Churchill Downs seems to be, its restaurants, its bars, its vast halls and betting windows, its milling throngs, closed circuit television, its wild people who never go outside to watch the races but sit, eternally glued to their racing forms—it would seem they would bet on themselves before they trusted in us to bring in their fortunes—all that seems a million miles away. On this side is still the barn. (Churchill Downs has 1,200 stalls, 50 barns.) And the warmth of the fresh hay, the cool spring water they give us, mingle with the memory of the nice snooze I had before I came here. (Ninety minutes I lay down for. Most horses are so nervous they paw through the floor.)

The outriders are urging their horses on, eyes—theirs, not ours; ours are fixed on the distance of around and back again—study jocks and mounts, looking, hoping for weaknesses, faults to be taken advantage of. The condition of the track, “That loam you have at Churchill Downs sticks to your face like cement when it flies up,” says one trainer: The brass of the post horn—a recording even on Derby day—becomes, with the shouts and urgings a welter in our ears; the gate breaks and the last of life for which the first was made begins. Three camera towers grab us from three different angles, freezing us in our rage for honor. Motion picture film flies over the wire to a hot developing room; is sent back to the stewards for viewing any infractions: horses bumping, crossing over, impeding the progress of another horse. None. A clean race.

There’s a party in the Director’s Room after the race. Champagne and very select company. Seventy-five invited guests. I heard Bob Gorham, one of the officers of the track, bemoaning having to turn down some senator. I’ve heard them talk about that room, prints of Epsom, our Derby, now a print of me with Ron and Lucien, the six tufted black-leather chairs, scrolled, Victorian, deep, downy. The quiet butlers who fill your drinks before they’re empty. Of course, we have our own party. But we still had the Preakness and the Belmont to go.

Now above the roses, I wear the Triple Crown, the first winner of it in twenty-five years. Perhaps the Belmont and the Preakness were more spectacular runs for me—thirty-one lengths beats the dead heat syndrome—but nothing ever seemed to capture the stopped-heart thrill of racing like the Derby. And even more than my being the Triple Crown winner, people—especially those who come to see me in Kentucky where the land rolls gently, almost sensually—those people always say, “Turkey dinner, Derby winner.” And thank heaven I’m protected. Fans would grab for souvenirs like I was a rock star. And, after all, I only have one suit.

Sometimes, I think of racing days as I watch the mares and colts frolicking across the meadows at Claiborne, the beautiful Hancock farm near Lexington, Kentucky, and the swans stretch their lovely necks on the meandering stream across the road from the white-columned house where the Hancocks have lived for so many years, and I wonder about the value placed on my blazed head. Six million dollars. Plus the money earned racing. Could anyone be worth that? And calling me ‘horse of the century.’

If another horse wins the Triple Crown next year, will he be the horse of the century? That horse won’t have the three white socks and blaze, won’t be a public relations item, won’t be the subject of postcards and tee shirts, the recipient of millions of letters, and the donor— yes—of charity on a colossal scale—no, I don’t just mean the taxes my owners have paid on my earnings. I mean the windfall to the state charities which benefit from betting. People were so thrilled, especially the two-dollar bettors, at having bet on me and at my winning, that hundreds of thousands of ticket holders did not cash in their tickets, preferring to hold them as souvenirs. “And that other horse won’t be playful as a puppy,” says a stableman at Claiborne.

“You just don’t think of a horse that strong,” says Mrs. Tweedy, “being that kind.” “Secretariat’d never be mean,” says Lawrence Robinson, my best friend at Claiborne, and the man in charge of the breeding barn.

There are other friends here too. “Snow,” a man whose face always seems to get into every picture with me. Pick up any magazine, and there’s Secretariat. And Snow. Then there’s “Buster Brown,” or some people call him “Charlie Brown,” a half cairn terrier, half mongrel, and four other halves. He slips into my paddock under the gate—”He wouldn’t dare go into any of the other stallions’ paddocks,” says Lawrence, and I have to chase the little mutt out. Then there’re the Hancock racing colors—bright orange and black—and they’re friends too. I know somehow the days of glory aren’t really over, that a new crop of colts will be bounding across the meadow next year and that they will bear my blood and the blood of my sire, the great Bold Ruler whose stall is home for me now, and all the way back to the immortal Eclipse, the immortal English sire of the eighteenth century. And I remember five hundred of the darkest, reddest roses; small, tight buds, thorns stripped, draped over my withers. And I know of the pride of the woman who makes the rose wreaths and has since the 1930’s. “Never,” she says, “has a single rose fallen off before being put on the horse.” And I think that maybe one day, one of my sons will stand there and receive that same glory. And to tell the truth, I’m a little jealous.

Protecting Animals from Beasts

There was a time in this country when cruelty was hard to see.

Everyone knew what it was. They recognized it in the attacks of Native Americans on settlers, but they had a hard time seeing it among themselves. Life was hard. Cruelty, many assumed, was necessary — unpleasant, perhaps, but expedient.

But cruelty and brutality didn’t sit well with the ideas of liberty. The patriots of the new country were rightly suspicious of any “rule by force.” In the years following the Revolution, Americans started to recognize how cruelty was often used for domination — of the poor, the sick, the insane, of children, and women. By the mid-1800s, they even began to see cruelty in the system of slavery — or, rather, they started to acknowledge what they’d already known.

In time, the widespread practices of mistreating animals also became clear. The Post helped raise public awareness though numerous articles of the 1860s.

Here, for example, they denounce the cosmetic mutilation of dogs:

“Sir Edwin Landseer, one of the judges at the dog show in London, England, endeavored to exclude all dogs that had been mutilated by ear-cropping or otherwise. The principal reason… is, that the cropping of ears is most and hurtful of the dog… All dogs, more or less, require to be protected from sand and earth by overlapping ears; but especially do terriers, literally “earth dogs,” the species which, of all others, is most persecuted by cropping.

“The only excuse that can be set up for the system is a delusive one. It is said that fighting dogs fare better with their ears cropped, and the exigencies of fighting dogs have set the fashion of all others… Leave the dog his ear, and the assailant’s grasp of the sensitive gland [within] is impeded by the folds of the ear, and rendered much more feeble. Thus, even to the fighting dog, the long ear is a positive defense.” [Dec, 6, 1862]

Curiously the reporter accepted commercial dogfighting as an inevitability. (Dog fighting has been illegal in all states since 1976. The last state to outlaw cockfighting did so in 2008.)

The Post pointed out potential abuse of farm animals:

“Kindness must be constantly exercised toward milch cows, and we might add towards all domestic animals. Very often young cows are restless or irritable, especially during the operation of milking, but whatever the cause gentleness is the only treatment that should be allowed — violence or even harshness never. There are many causes after recent calving that may produce inquietude, but no other remedy will be effectual. A young animal never forgets ill treatment, and a recurrence of similar circumstances will remind the cow of former punishment.” [Sep. 2, 1871]

“Stabling of every description is an evil. It is impossible a stable should be so built that it will allow the animal one half the freedom he enjoys when loose out of doors… The fact is, our modern stables throw the stress upon the back sinews or flexor tendons, and thus prepare many an animal for injury… Nor is this all: the stall is perfectly at variance with the habits of the horse: he is evidently gregarious, [living] among crowds of his fellow-creatures; the stall dooms him to solitude, and the groom sits behind to see he does not put his nose over the division, only to look at a comrade. In many stables the stall is so small that the horse cannot turn around; he can lie down perfectly at ease in very few.” [Nov. 22, 1856]

“In offering Prizes for animals in agricultural meetings, distinction should be made between those smothered in fat, by which the framework is totally concealed, and those whose proportions are visible, though well covered with wholesome meat… It may be amusement — there is no accounting for taste — to watch an unfortunate quadruped daily increase in size, till he becomes unable to stand without assistance of his attendant, who is obliged to cram him by hand. This may almost be said to be cruelty to animals for no good purpose. [my italics]… The first thing to be considered in regard to stock is not who can, regardless of cost and trouble, bring before a wondering public a live mass of grease, which, after a gleam of astonishment has passed away, fills the mind with a sickening sensation and compassion for the sufferings of the brute – [quoted from the London’ Gardeners’ Chronicle, Feb. 7, 1857]

The Post even raised concerns about the abuse of animals in the name of science:

“In the veterinary colleges of France, especially in the great establishments of Alfort, and Lyons,… the pupils are regularly instructed in surgery by cutting up living horses… This fiendish lesson is given regularly twice a week; when the doomed horse is cast, and is then subjected to all sorts of surgical operations… Steel, and fingers guided by stony hearts, invade the poor animal at all points; these operations on the same horse lasting from nine in the morning until four in the afternoon, unless, indeed, the poor animal escapes from the diabolical torments inflicted upon him, by dying in the meantime… Vivisection is condemned everywhere but in France, as absolutely unnecessary to the successful cultivation of the veterinary art.” [Nov. 17, 1860]

Americans in these years lived closely with horses. They relied heavily on them for transportation and farm work. The practices of beating, starving, whipping, and maiming horses was more than just barbaric, it was ingratitude.

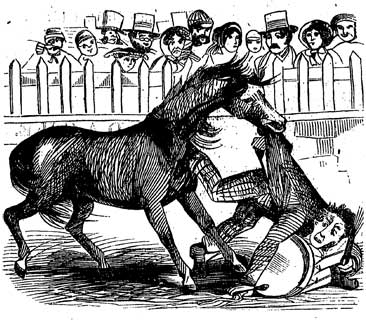

“We would suggest to the society for the prevention of cruelty to animals — and an excellent and greatly needed society it is — to take a glance occasionally at the manner in which horses, monkeys, etc., are treated in our circuses. The whip, we are included to think, is much too freely resorted to by those who have the training of these co-called brute performers… Forepaugh’s Menagerie and Circus is now on its travels — an excellent Menagerie and a very poor Circus — but what pleasure can be derived by any intelligent and tender-hearted audience, from the displays of the leading horse… To see an animal naturally of a very fine intelligence, with its high spirits all broken down by the whip, and shivering and trembling over the difficult feats required of it, so far from giving pleasure, almost makes a sympathetic observer sick. [April 11, 1868]

The Post’s editors frequently praised the work of John Rarey, who had developed a method for horse training that avoided all beating and punishment.

“The horse, according to Rarey, is happier in finding his master than he could be without him, provided the action of his master be kind, gentle, and adapted to the needs and instincts of the horse. Make him feel that you have him utterly in your power and that your power is kindly, and the horse is your happy and affectionate servant henceforth.” [Feb. 16, 1861]

In praising Rarey, the Post was voicing one of its strongest arguments against cruelty to animals: that cruelty is never contained. The idea of using pain and fear, even on dumb animals, pollutes a democratic society. “Cruelty to an animal touches every human man and woman precisely as cruelty to a human being does — the only difference being one of degree and not of kind.”

“The force and benefit of Mr. Rarey’s precepts and example in bringing about a more humane and sensible mode of dealing with horses, can hardly be over-estimated. And in rescuing horses from foolish brutality, he is aiding in overturning the general reign of brutality and ignorance in the world. If horses can be managed by calm force used intelligently in a spirit of kindness, why not children, why not men? We therefore enroll the name of Rarey not only among the benefactors of Horses, but also among the benefactors of Mankind. [Feb. 16, 1861]