Cold Comfort: My Night in an Ice Hotel

We’ve just left a fine room at the Fairmont Le Château Frontenac, a grand hotel in Québec’s quartier historique, and we are driving on a dark country road. It is 20 degrees below zero Celsius (–4 degrees Fahrenheit). We are on our way to the Hôtel de Glace, the Ice Hotel, full of excitement and dread.

“It’s not that bad in the rooms; just minus five,” a waiter told us a little earlier as we had our last meal before departing. Then he added, reassuringly, “You don’t really feel it. It’s a very dry cold.”

The taxi driver, a francophone Québécois, doesn’t speak much English. “I hope you have a freezing night!” he says after I pay our fare. I think he means it in good spirit, that this is what you’re supposed to say when people are going off to sleep in a modern igloo, the way theater people say “break a leg.”

The path to the hotel has patches of black ice. A million stars look frozen in space, and it is so wondrous it could take your frosted breath away. But your breath comes out in white puffs, like cartoonist’s thought bubbles that say, “… boy, it’s so cold I can’t even think of something funny to say.” At this moment the cosmos seems considerably less miraculous than central heating.

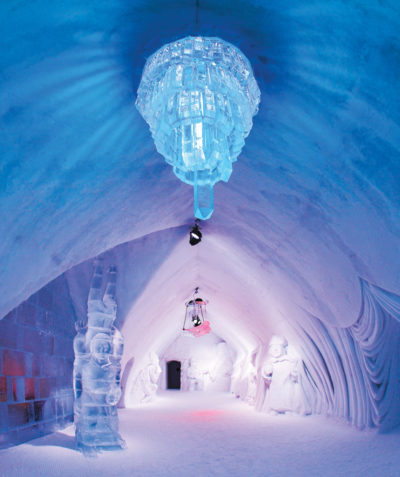

Every kid, I suspect, at some stage wishes to sleep in an igloo. The Hôtel de Glace is a whole complex of them, interconnected halls and chambers cut and carved from 30,000 tons of snow and 500 tons of ice. There’s a chapel with an altar and pews, a bar, and a room with an indoor ice slide. Another space is a gallery of whimsical ice sculptures: an old-fashioned landline telephone, an enormous volume like a Gutenberg Bible, and a vintage deep-sea diving helmet. There are whole dogs and a giraffe’s head and neck sticking out of the floor. A 600-pound ice chandelier with long ice pipes hangs from the ceiling.

The 45 guest rooms come in a variety of shapes and dimensions. Ours, the Snowflake Room, has walls carved with patterns that suggest magnified snow crystals. Queen-size mattresses are on two platforms made of ice. A pedestal and two chairs on either side of a table are fashioned, of course, out of ice.

The Hôtel de Glace would melt on its own, but due to concerns of insurers, they bulldoze it each spring. It takes 15 artists and 35 workers six weeks to create it anew every winter, and it’s open from early January until late March.

The complex has colored lighting that keeps refracting through the ice and settling on the snow like Technicolor dust. The other visitors, mostly Canadians, are a merry crew. Québécois are big on EDM (electronic dance music), even when they’re wearing snow pants and parkas. I admire them for it. When I put on clothes like that I’m even stiffer than usual. They dance on the glazed surfaces of the ice bar and pose for photos with frozen smiles around a flaming chiminea. The hotel brings out blocks of ice and little picks for a sculpting contest. People chip away, making little snowmen or ice hearts.

We go to the spa, which has hot tubs and saunas, and change into bathing suits and robes in a conventional building located behind the ice complex, where there are also toilets, showers, and lockers. The hot tub’s submerged lighting catches the steam hovering just above the water’s surface. We take off our robes and plunge like soldiers into the safety of a trench.

This is all a game of catch with the cold: First it has you, and then you escape by slipping into the hot water, and you lie back looking at the stars and enjoying the hot water and the jets from the Jacuzzi. Strangers want to know where you came from. You’re like brothers in arms facing the same adversaries. Cold hands, warm hearts.

Then it’s time to get out, because you know you can’t stay there all night. There’s no escape. The cold has you from the bottoms of your feet as they touch the icy floor to the top of your wet head. It licks your raised, weeping flesh.

And you give it its taste on your way to dry off and change clothes and get ready for the main event: sleeping. We return to our Snowflake Room and twist ourselves into the sleeping bag liners and stretch our limbs into the mummy bags. I am glad for the advice we received on arrival. For example: put on fresh socks. If you wear the ones you sweated in already, the cold air will circulate and your feet will get colder all night.

The liner works beautifully. There is, I’m sure, some science to this, something about airflows and trapping heat between layers. But what you need to know is that what starts out warm and dry stays warm and dry, and that when the warmth surrounds you, it feels a lot like complete love, the kind of all-enveloping peace you last experienced in the womb.

There is, though, a kind of low-intensity anxiety. Fear, for one thing, that the warmth won’t keep and you’ll wake up freezing. And fear, for another, of not sleeping, of an eternal dark night shivering and shaking like a detox patient. But cold exhausts the body and fear exhausts the brain, and soon enough your wife taps you to complain: You’re snoring.

An arm falls out, and the cold air coats it. Breathe through the nose and the air freezes your nasal passages, and you wake up with apnea; breathe through the mouth, you get a dry throat. I fall back to sleep. The ski hat I brought along comes off, and some arctic spirit massages my head and breathes on the rims of my ears. I twist in my mummy bag to reposition. The bag is rated for 28 below. Eventually it gets to -26. That’s the temperature outside, of course. Inside I have no idea. I suspect it’s getting colder all night, but it’s possible I’m just weakening, waves of cold battering the ramparts of my being.

I’ve slept outside, exposed to the elements in deserts and jungles, and I’ve been in a few really grim hotels, too, but now it comes as a revelation that I am, in reality, a soft man.

I dream of the hours of the night. I dream that it’s morning. Even so, unlike a few guests who bail each night, the one thing I wouldn’t dream of doing is running for

heated shelter. I’d rather be mummified by frost, a stiff on my bed of ice, than to have quit. I have my pride.

In the morning, light pours in through the hole in the ceiling that’s there for ventilation. Light is not just illumination. It brings news: I have survived. This is a modest achievement. I think of the great polar explorers, Amundsen, Scott, Shackleton. They had to melt their sleeping bags before climbing into them. The biggest advantage a modern adventurer has today, a modern adventurer once told me, is not GPS or satellite phones but technical fabrics and advances in footwear.

I lie there a while, enjoying the soft light and serenity, and also girding myself to the idea of unzipping the bag and climbing out. In the end, it isn’t courage that makes me move but a full bladder.

I get up quickly, jiggling a foot into a shoe, careful not to land an unshod hoof on the snowy floor, and give my stiff spine a fillip. Then I stand in a series of shivers and spasms, like a foal getting itself upright, and, pulling a jersey over my swollen dome, I shuffle forward and lurch toward the finish line: a hot breakfast, indoors.

Todd Pitock’s last piece for the Post was “The Healing Power of Baseball in Japan” (March/April 2018), which won an award from the American Society of Journalists and Authors.

This article appears in the November/December 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.