Friends, Foes, and Formality: The Presidential Press Conference

Never, in its long and difficult history, has the relationship between president and press been so rancorous. Major newspapers are repeatedly challenging President Trump on his facts, and the president has referred to the country’s leading news sources as “the enemy of the American people.”

We’ve come a long way from Revolutionary days, when Thomas Jefferson said he’d rather have a free press and no government than a government and no free press.

Presidents have always worked to gain the approval of the press, knowing how newspapers can build public support for policies. But for most of our history, presidents kept their distance from reporters. In the 1900s, President Theodore Roosevelt began hosting informal press conferences, but he was selective of which reporters were invited, and he prohibited any reporter from quoting him. Presidents Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover all held formal press conferences but would only answer their choice of questions, which had to be submitted in advance.

Franklin Roosevelt broke with tradition by inviting reporters into his office and answering questions directly, setting the precedent that is still followed.

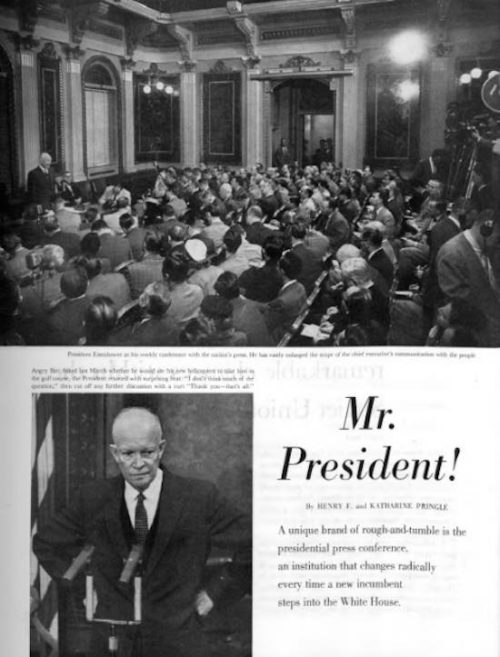

In “Mr. President!” Henry and Katherine Pringle offer a glimpse of a more decorous era in Dwight D. Eisenhower’s White House press room. It’s refreshing to read of the days when press and president could earn each other’s respect.

President Eisenhower had been dealing with the press since he was the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe during World War II. One of the chief reasons he was given that post was his ability to handle criticism and win support from his critics. Rarely did he show resentment or hostility toward people who fired questions at him. When he did speak his mind, he could show a dignified outrage, calling one question “the worst rot I have heard since I have been in this office.”

And to another, he gave what, for Ike, was a harsh critique: “I don’t think much of the question.”

Despite the occasional blunt response, Eisenhower appeared to respect the reporters, and they respected him. The current state of the White House press room is far different, and it seems unlikely that civility will make a reappearance anytime soon.