North Country Girl: Chapter 51 — Big Pink and the Invisible Man

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

James and I were in his hated hometown of Winnipeg. He had been summoned there by Elena, the daughter he had deserted years ago. As a family reunion it was a disaster; James showed no desire to spend any quality time with his chubby, homely daughter, who was more introverted and tongue-tied at 22 then I had been at 15.

Having completed his obligatory visit with Elena, James rooted out his best friend from high school, Robert, whom he had heard was doing well financially, but not exactly through legal means. Luckily for James, his pal was not locked up in the hoosegow; he was currently out on bail waiting for his next court appearance.

I felt right at home as we drove through Winnipeg to Robert’s house; his neighborhood was almost identical to the middle-class one I grew up in: big red brick houses on spacious, carefully maintained lots shaded by tall pines and paper-barked birch trees. We pulled up to one of these stately homes. A pretty blonde woman invited us in with a tight, brittle smile, introduced herself as Robert’s wife, and led us into the living room where Robert was waiting for us.

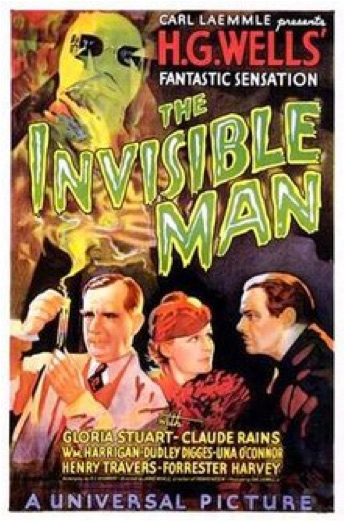

Robert’s head and hands were completely swathed in white bandages; he looked like Claude Rains in The Invisible Man. Where his face was supposed to be there were four holes poked out for eyes, nose, and mouth; his hands were oversized, slightly grimy gauze mittens. The charge he was facing was arson for profit. Robert may have been a successful criminal, but he had obviously completely screwed up this last job.

Robert’s nervous blonde wife brought out a round of Seagrams and Seven-Ups, my alkie grandfather’s tipple of choice but not mine; the rich, spicy, evocative smell of the whisky made me feel that I was seven years old.

Robert took his highball through a bendy straw, squeezing his glass between his stiff bandaged hands like a raccoon. James never asked “How’re ya feeling?” or “Oh boy, I bet that stung,” or made any reference to the fact that we were having a conversation with a man who didn’t have a face. Unlike sitting with someone who has a cast on their arm or leg, there was no humorous recounting of how Robert came to have these injuries. My own face twisted into a rictus of a smile as I tried to get through the inevitable small talk: where I was from, how I liked Winnipeg, how long the drive from Chicago had taken. I was relieved when the conversation turned to anecdotes of boyhood hijinks and whatever-happened-to’s, although I couldn’t seem to relax my face.

After they had exhausted the boring gossip about their old schoolmates, Robert said, “Hey, why don’t we all go up to my house on the lake for a few days?” I did not want to look at this talking mummy for another second, but James had already accepted, probably delighted to be out of the reach of his daughter.

In Minnesota if you had a place on the lake it was a homey cabin, with appliances from the 1940s, one or two bunkbeds in every room, musty furniture, a deck of cards with “two of clubs” scribbled on a joker, tangled fishing gear, and either electricity or indoor plumping, but never both. That was what I had pictured in my mind as we drove through the forest surrounding Lake of the Woods, catching glimpses of the shining silver water between trees. It all seemed so welcoming: the almost black firs contrasting with the gleam of white birch, the hand-painted signs posted at each turnoff with the owners’ names or the corny names of their cabins — “Dunmovin”, “The Oar House,” “Dock Holiday” — were all as familiar to me as breathing. I almost forgot that riding in the passenger seat in the car in front of us was a man with no face.

James followed that car when it turned at one of those signs, a white board with “In the Pink” neatly painted on but wanting a bit of touching up. James’s El Dorado bumped down a narrow dirt track towards the lake where we found not the rustic cabin I had expected but a sprawling modern white brick ranch. We walked into an immense living room with three sides of floor-to-ceiling windows that held all shades of sky and lake blue. Along the shore, the dark green forest was as perfectly reflected as if the water were a mirror. Next to one set of windows were twelve chairs surrounding a lengthy dining table. To the left I could see into a spacious, sleek kitchen. Robert had already told us, “Plenty of room! We’ve got four bedrooms, each with its own bath!”

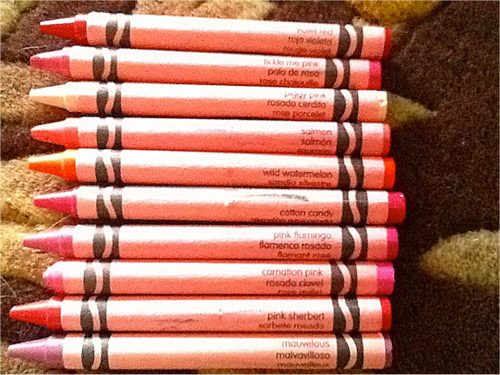

There was only one thing wrong. Everything inside the house was pink. Not just any old pink, but the exact shade of a carnation pink Crayola crayon. The sofa, the rug, the paint on the walls. The bathtubs and sinks. All the modern appliances in the kitchen. That big dining table and all the chairs.

Robert, raising his voice to be heard through his mask of bandages, showed us around, the proud owner of all that pinkness. “You wouldn’t believe the deal I got!” he boasted. When the woman who had owned and proudly decorated the house had died, there had been no other offers, and the heirs couldn’t wait to get that pink elephant off their hands.

It was like being in a brain, or an intestine, all that throbbing pink. As I soaked in the pink tub later that evening, I tried to imagine different scenarios for this obsession, but failed to come up with a likely story, as it was obviously just madness.

Not only was everything pink, everything was really nice. That tub was huge, the hot water inexhaustible. You sunk so deep and comfortably into the pink couches, all you wanted to do was sip a cocktail and gaze out the picture window at the lake. The wooden dining table and chairs were heavy and substantial, all painted and shellacked so they shone like a manicured nail. Where could you even go to buy a pink Whirlpool dishwasher? I wondered.

“You wanna see something funny?” Robert asked and led us down to the lake. There, at the end of the dock, deep in the water, under the flashing pike and drifting waterweeds, was a pink refrigerator. A salmon pink refrigerator. The wrong shade of pink. When it was delivered to the house, Mrs. Pink had freaked out and made the delivery men dump it in the lake. The big two-door refrigerator that was currently purring away in the kitchen perfectly matched the stove and the walls and the cabinets and everything else in the pink house.

“Some house,” said James. “How long have you had it?” Robert bought the house three years ago and hadn’t changed a thing. He didn’t see anything wrong with the interior, everything was first class, custom made, top of the line. So what if it was pink?

During the day I spent as much time as possible down at the dock reading or swimming or gazing out at the lake, trying not to think about James losing his fortune and his mind, his unhappy twice-rejected daughter, the bandaged arsonist with third degree burns, or the crazy house looming behind me. I lingered by the water till the loons started their plangent calls, the signal for swarms of enormous mosquitoes to descend and drive all humans inside, where three of us dined off pink plates at the huge table, Robert alternating between highballs and a disgusting looking liquid food sucked up through a straw.

James never mentioned his daughter Elena, and I certainly was not going to bring her up. He was restless as a chained wolf at that lake house; the Winnipeg Free Press did not carry even yesterday’s NYSE reports, and his requests for a New York or even a Chicago paper were met everywhere with disbelief: why would you want a newspaper from somewhere else? There was no TV at the lake house, Robert apologized, no reception out there in the north woods. James, not a lover of country life under the best of circumstances, cut our visit short. We said goodbye to that ranch house of insanity. James went to shake hands with our host, slapped him on the back instead, and we drove back to Chicago.

The news waiting for James was especially bleak. Highline shares were tumbling faster than ever. James spent the day yelling at the TV, trying to get his broker — who he now was convinced had intentionally dumped that piece of shit stock on him — on the phone, or staring into space.

I needed my own money and had a harebrained idea of how to earn it. I was going to be a model. I had already made one commercial and earned $100, why couldn’t I do two or three commercials a week?

I didn’t have a copy of my Mexico commercial. I didn’t have any professional photos. And I topped off at 5’3”. When I showed up at the Ford Modeling Agency the receptionist gazed several inches above my head, where my face was supposed to be, then showed me the door. Ditto at Wilhelmina.

In the Chicago Yellow Pages I found a small ad for the Ann Geddes Modeling Agency, which turned out to be a waiting room with three chairs, an unoccupied receptionist’s desk, and a tiny private office where Ann Geddes, a former model herself, was waiting for me, along with her husband Silver, who was a stockier, grayer version of James, and who, true to his name, wore massive Navajo silver rings and bracelets and a silver hoop in one ear.

“When’s your birthday?” Ann asked.

“Oh, I’m twenty-one.”

“No, the date and the year and if you know it, the time.”

Having gotten that settled, I started babbling about my Mexico tourism commercial (leaving out that I had been the emergency replacement) and my acting experience in high school (leaving out that the experience consisted of three lines in “You Can’t Take It With You” and the co-star role in a student-directed one-act play).

Ann Geddes was ethereally gorgeous, with long, rich red hair and milky skin unmarred by a single freckle. Her beauty was not intimidating. She was as warm and friendly as an older sister; it was easy for me to rattle on like an idiot. Silver, who had been scribbling on a pad the whole time, interrupted my life story: “I’ve got it!” He was an astrologer; while I was trying to talk my way into being a model, he was casting my horoscope. He announced that despite my shortcomings, the stars were aligned and the Geddes Agency would be happy to represent me, their take ten percent of everything I earned.

This did not mean I would have steady work or a regular income. The star of the Ann Geddes Agency was another small blonde, who was a lot prettier than I was and had several commercials under her belt that she actually had copies of. When the call came in for a model to pose next to a refrigerator or power tool to make it look bigger, she was sent. I was the backup blonde.

I did not discover my second banana status until later. At the moment I was thrilled: I was officially a model. Ann blithely handed me a contract to sign and a Xeroxed contact list of every photographer in Chicago, from the newest Chicago Art School graduate to Screbneski. It was up to me to call on all of them, trolling for modeling work.

But before I could do that, I needed a composite, an eight by eleven calling card with a pretty head shot on the front and photos showing a range of commercial personas (young mom, career girl, sportswoman) on the back to leave with the photographers. Ann took a red pen and scrawled a circle around one name on her list.

“Go see Frank Wojtkiewicz first. He might take composite photos of you for free,” she said, her face as smooth and blank as a china plate.

My Wood Stove

We bought our first house 20 years ago, still live there, and will die there if we have any say in the matter, which I suppose makes it our last house, too. It’s not a perfect house — the kitchen, where we spend all our time, is on the north side of the house and doesn’t get much sunlight — but the house is otherwise suitable and fits us well. The best feature is the kitchen woodstove, which we fire up in fall and keep burning through late winter or until we run out of firewood, whichever comes first. Like most purchases I’ve made, it was impulsive but has given us more pleasure per dollar than anything we’ve owned.

I haven’t yet discerned whether we own the stove or it owns us. A man who heats his home with a woodstove has unwittingly signed up for a full-time job: cutting, hauling, and stacking firewood seven months of the year to stay warm the other five. Except for this man, since I hire a woman named Kelly to bring me firewood each fall. Kelly drives a school bus in our town and cuts firewood the rest of the year. It would be selfish of me to cut my own firewood when Kelly so obviously wants the work.

This still leaves plenty of work for me, carrying the firewood in from the fence row to stack on the back porch, waking early each morning to load the stove, tending it through the day, staring at the fire each evening contemplating matters great and small. Devoting one’s life to reflection can be tiring, and many evenings I fall asleep while staring at the fire, exhausted by my labors.

One of my favorite things to think about while seated by the fire is how much better the world would be if everyone were seated by a fire. While gazing at a fire, I’ve never thought ill of someone else or wished them harm in any way. Indeed, just the opposite has happened. A man I didn’t care for once appeared at our door on a winter’s evening. I invited him in and ushered him to a chair in front of the fire. We sat for a pleasant hour, philosophizing, and by the time he left, we were thick as thieves. The United Nations should have a woodstove instead of a dais.

Our stove was made in Norway by a company named Jøtul, which has been making stoves since 1853. If our woodstove had been made in China, I probably wouldn’t have bought it, but I liked the idea of it being built by Norwegians. I’m sure Chinese workers do just as good a job as Norwegian workers, so I don’t know why I feel the way I do. I don’t like what it says about me that I automatically assume Chinese workers are less devoted to quality. The Forbidden City Imperial Palace in Beijing was built in the early 1400s and is still standing. I’m fairly certain it wasn’t built by Norwegians. If it had been built in America, we’d have torn it down and put up a Walmart. This is the kind of thing I think about while seated by the fire.

I should probably mention that we have a second home, my wife’s ancestral farmhouse in southern Indiana. We put a Jøtul woodstove in it last spring, so now I can think down there, which has thrown my whole life out of whack since I go there for the express purpose of not thinking. Lately, I’ve been thinking that owning two houses with woodstoves is wearing me out, and I should sell one and live in the other. Except now I am a prisoner, bound by cords of memory to the first house where our children were reared, tied by marriage to the second, where my wife was raised. And so, come winter, I own and am owned, captor and captive alike, lighting one fire while dousing another.

Philip Gulley is a Quaker pastor and the author of 22 books, including the Harmony and Hope series featuring Sam Gardner.

This article is featured in the January/February 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

No Place Like It

Home. The word resonates right to the center of who we are. It connects us to family, memories, our communities, even to ourselves.

For some, home is primarily a nest that nurtures, a refuge that protects, a delight that allows us to exercise the playful side of our natures. For others, it’s a sturdy structure of brick and mortar that anchors us—or a shell of aluminum that sets us free.

Even more, as architect Claire Cooper Marcus points out in her book, the aptly titled House as a Mirror of Self, our homes reflect our priorities, our values, and our histories—they are all on display through the places where we choose to live. On the following pages, you’ll meet some amazing people whose homes do just that. We think you’ll find their stories both familiar and surprising.

The manner in which we design, adapt, and furnish our homes says a great deal about who we are, too, as individuals, as families, and as a society. New homes are getting smaller—the era of the oversized “McMansion” is over (for now). At the same time, households are expanding to accommodate two, three, even four generations under one roof. Revolutionary products and services are allowing older homeowners to live long lives, safely, happily, and independently in the same house; meanwhile, wireless and integrated “smart” technologies let others redefine their notions of home entertainment, convenience, and comfort. As you’ll see, these and other housing trends in America are more than just the bloodless facts and statistics of a multibillion dollar industry—they are the very measure of our hopes and dreams.

As twilight settles over Boston’s historic Beacon Hill neighborhood, Victorian gaslights glow against the aged brick row houses that have stood here for close to 200 years.

Inside one of the elegant homes here, Susan McWhinney-Morse sits in the living room of her home and counts her blessings. “I have everything,” says the active septuagenarian. “A garden in back. A deck off the kitchen. A beautiful living room with high ceilings, exquisite plasterwork, and two wood-burning fireplaces. My four children all grew up in this house, and they loved it. They can’t imagine not coming home.”

The house has been through a lot of changes since Susan moved here with her first husband some 40 years ago. After that marriage ended in divorce, Susan took in boarders to support herself. Her family occupied three floors, but with other floors in the house, there was plenty of room for paying guests.

“The house has been so flexible,” Susan says. “When I married David Morse 15 years ago, the kids were all grown up, and we really didn’t need all this room. So we downsized within our own house. We turned the house into three separate apartments. We have the main floor, four bedrooms, and David and I each have our own study.”

To make sure that she and David are able to stay in their home as they age, Susan and her neighbors formed a community organization that offers services to Beacon Hill residents: dog walking, house painting, garden weeding, grocery shopping, rides to the airport,

even someone to help rearrange the furniture.

“The idea was to be on Beacon Hill forever,” says Susan. “The people here have a great sense of community, of neighborhood, and of caring for who we are and what happens here. We started with 11 people who were wild about the idea, and it’s just grown.”

As the Home Roams

Stella rocks. A 200-square-foot Airstream Excella, Stella measures 29 feet at her longest point. She’s covered in polished aluminum, and her interior boasts wood floors, custom cabinetry, an antique metal backsplash in the kitchen, a stained-glass window, sheer window treatments throughout, and a couch that flips into a bed. In short, all the comforts of home, for only $15,900, delivered to the Maryland driveway of Ramona Creel and her husband, Matt Boorstein.

“Stella’s hip and cool and awesome and I love her,” says Ramona. So much so, in fact, that she and Matt decided to sell their house, reinvent their careers, and take to the open road. Permanently.

“The house thing just wasn’t working for us,” says Ramona. And they were miserable in Maryland, spending nights and weekends fixing up the house and days working to pay for it. Plus, all that work cut into their travel time.

“Some people are perfectly content staying at home, living in the same town their whole lives, not really caring if they see the world,” Ramona writes from somewhere near Atlanta. Or San Diego. Or maybe it was Louisiana. “Not me! I inherited busy feet from my father. Nothing excited him more than jumping in the car and taking off to someplace he had never been. I’m the same way.”

Matt is, too. Ramona’s husband was a military brat who grew up wandering the country. Initially he worked in interior design while Ramona, who has a degree in social work, found homes for displaced families in Florida. Eventually, she started her own business as a professional organizer of homes and offices, while Matt started work developing her business’ Web site. To earn money and remain mobile, Matt morphed into a full-time Web designer. Now, Ramona coaches clients via the Web, with occasional meetings when Stella pulls into an RV park, and Mark runs his business online. Wherever they can hook up to a server, an electrical outlet, and a water faucet, they’re in business. It’s a life that suits them well. “It just feels like the right path,” says the woman with busy feet. “We didn’t want the house. We don’t need the big screen TV. We want the experiences.”

Where are they off to next?

Ramona laughs. “Florida. We follow the good weather.”

Under One Roof

Standing proudly in front of the chicken coop on his grand-mother’s three-acre homestead in Starksboro, Vermont, 8-year-old Christopher Gravelle carefully holds out two eggs so fresh they’re still warm from the hen. He carefully explains to visitors the hows and whys of raising chickens as he walks toward their outdoor pen. His sister, Courtney, a 6-year-old blonde elf in a lavender parka and sparkly shoes, bounces along beside him. “Know what?” she asks, pointing across the yard. “That’s my bike!”

Along with their hens, bikes, and cats, Christopher and Courtney have lived here in the gray clapboard house all their lives. Their grandparents, Bob and Sue Baker, bought the property 28 years ago to raise their daughters—Lori, now 26, who works at a kitchen-and-bath shop in Burlington, 27-year-old Jessica, and 31-year-old Shelly, a stay-at-home mom to Christopher, Courtney, and 9-year-old Thomas.

“The house was old but the price was right,” says Sue. “And we liked the neighborhood.”

Situated between a two-lane rural highway and the wooded foothills of the Green Mountains, the house, with its fenced-in front yard, sits on one side of State Route 116 with neighboring homes spaced well apart. A cornfield is across the road.

“I love my property,” says Sue. “I have two apple trees, a big garden, a bird feeder, we’re bordered by Lewis Creek, and the kids can fish.”

The big draw for her was the yard. “When we first moved here, we had a maple tree by the fence that shaded the yard, and there was one that shaded the house,” Sue remembers. “Those girls could play in that yard all day. They had their swing out there, and it was nice. During the summer, you could sit in the living room and feel the breeze blowing through.”

As time went by, the kids grew up, Shelley got married and moved away, and Sue picked up part-time work at a local supermarket, a golf course, and a neighboring elementary school. But then Sue’s husband developed cancer, and nine years ago he died. Five months after that, Sue had a heart attack and quadruple bypass surgery.

Concerned, Shelley and her husband, Jason, moved back home with baby Thomas to give Sue a hand. Christopher and Courtney were born over the next couple of years, and things seemed to be getting back on track. Then Jason died of a heart attack, and Shelley was suddenly a single mother.

Things have been tough ever since. Sue was able to work part time as a cafeteria worker at the local Robinson Elementary School until her job was outsourced in budget cuts last spring. Lori has a job; Jessica and Shelley don’t. The family heated the house last winter with a woodstove and two kerosene heaters, but one of the heaters broke, and Sue didn’t have the money to fix it. That’s a concern in an area with below-zero temperatures in January.

But Sue shrugs it off. When something breaks down, generally the girls figure out how to fix it. “You learn this stuff as you go along,” says Sue. “We had a major toilet clog last week, so the girls became plumbers. They went and got plumbers’ snakes, took the toilet off, pushed the snakes through, had the septic tank pumped, and got it fixed.

“When you got family, you do what you’ve got do,” she adds. “This place has been a refuge for everybody.”

Big Little House

Benjamin Speed and his wife Sarina grew up on Maine’s rocky coast, exploring lighthouses and cracking lobster at the Bucks Harbor market. Then they headed for college in Washington State, and, like so many children, vowed never to return home.

After they graduated, Sarina went to work as a jewelry designer; Ben worked as a videographer. Both realized just how deep their roots were embedded in Maine’s sandy soil, how much they missed their folks, and how strongly they felt that the children they would have should be raised close enough to know their grandparents.

The two returned to Maine and rented an apartment. Ben got a job teaching film production with a local school and picked up a few extra bucks videotaping weddings, while Sarina continued with her design work.

But paying all that money for rent really bugged the practical Sarina. So the couple, in their mid-20s at the time and with a baby on the way, decided to build a house. And not just any house, but one that reflected their values—something large enough to meet their needs, but small enough to respect the environment and leave a reasonable footprint on the planet. A footprint, in fact, that measured 18 feet by 18 feet.

“People don’t need as much space as they think,” says Sarina, who grew up in an even smaller house. “We can’t have huge groups of people over, but for three people it’s more than enough.”

Aside from leaving a smaller environmental footprint, the house also makes sense in the current economy. “I wanted to build something so that if our jobs didn’t work out, we could still afford our house,” Sarina says.

Borrowing as little as possible from the bank, and with help from friends and family, the Speeds built the two-bedroom house themselves. “We did the basic framing, roofing, shingling, and insulation,” Sarina says. “The stuff that would take us too long to learn we farmed out.” As a result, the house—including its foundation and the road leading to the house—cost just $55,000.

With son Noah now 4½, and baby Larkin newly arrived, Sarina and Ben are planning to build on a third bedroom. “But the house will never be more than 800 square feet,” says Sarina, firmly. “And we’ll have the mortgage paid off by the time the kids go to college.”

Smartest Homes Ever

As history has proven, new technologies—from electric lights and appliances to radios and televisions—inevitably make their way into the home. When they do, they make life easier, more efficient, and more fun.

Tony Tessaro would agree. Standing on Mandalay Beach in California, the 60-year-old retired Wall Street trader is like a kid with a new toy. Only that toy is his whole home. And it’s a smart home. “I can control everything from my TV clicker,” says Tony. “Say I’m watching TV and you ring the doorbell. There’s a camera in the bell, so a photo of you pops up on the screen.”

Tony loves that the house “knows” who he is. “We have a two-car garage,” he says. “One side’s me, one side’s my wife, Mary.” When the garage door opens and she drives in, the house senses it’s her, then closes the garage door, lights up a path to her bedroom, and turns on her favorite music.

Trends in home technology are changing the way we come home and what goes on in the home, from lights and music to control of heat pumps and central air for energy efficiency, says Laura Hubbard, a spokesperson for the Consumer Electronics Association.

Companies such as Russound, for instance, offer customizable equipment that plays music in different areas throughout your home from a single device, controlling the system with iPod-like keypads. Some systems read smart tags embedded in a phone or a keychain and respond according to the preferences of the tag’s owner.

While advanced systems can cost thousands and require extensive remodeling, the do-it-yourself route offers affordable off-the-shelf systems. Take HomePlug, for example: This concept allows TVs and computers to communicate via the home’s pre-existing electrical wiring. Home automation is just the beginning, Hubbard says. In coming years, with the advent of the “smart grid”—a more efficient system of delivering electricity to your home—new home appliances will turn themselves on when it’s the most efficient time of day to do chores.