The Awkward Infancy of the Vacuum Cleaner

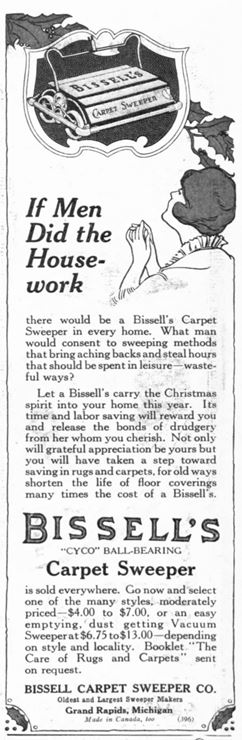

“If men did the housework,” a 1918 advertisement mused, “there would be a Bissell’s Carpet Sweeper in every home.” The sweeper — still a staple in many homes today — wasn’t as powerful a dust picker-upper as the nascent vacuum cleaner, but the developments around getting harmful debris up and out of carpet and rugs were already transforming everyday work for women. In the early days of suction, vacuuming carpet was a job for two; now, it needn’t require anyone at all.

In the 19th century, a list of chores for a woman to complete around the house was long and arduous. As proof, Catherine Beecher’s 1841 book, A Treatise on Domestic Economy for the Use of Young Ladies at Home and at School, offered 37 chapters of women’s responsibilities in the home. Beecher publicly proclaimed the importance of women’s housework, which she intended to strip of its “menial and disgraceful” reputation. She believed keeping house should be regarded with the same importance as a man’s labor because of its impact on the health of the family. Chapter 24 of her Treatise covers the best practices for the care of parlors: “Sweep carpets as seldom as possible, as it wears them out. To shake them often, is good economy … When carpets are taken up, they should be hung on a line, or laid on long grass, and whipped, first on one side, and then on the other, with pliant whips.”

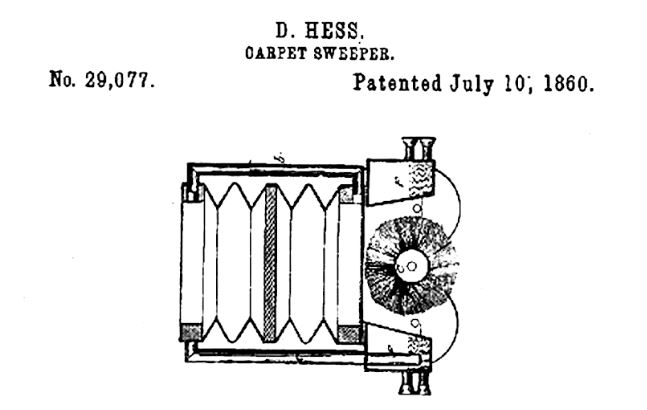

The introduction of some sort of machine to accomplish this task would have been a long-awaited and welcome relief. According to Carroll Gantz in The Vacuum Cleaner: A History, the first known invention of a sweeper that used suction was an 1860 patent granted to Daniel Hess of West Union, Iowa: “The nature of my invention consists in drawing fine dust and dirt through the machine by means of a draft of air, forcing the same into water or its equivalent for the purpose of destroying it substantially.” His concept included a bellows, similar to the kind used to stoke a fire, but it was never taken to market.

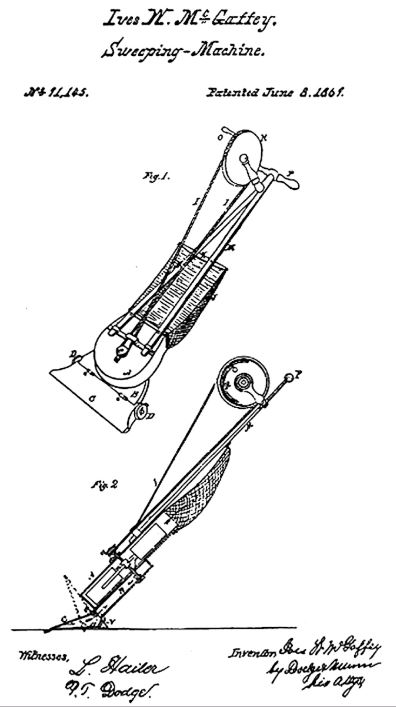

The latter half of the 19th century saw a flood of new inventions in the U.S., and carpet sweeping devices followed the trend, even if most of the patents were non-starters. Ives McGaffey’s 1869 machine resembled modern upright models, but with a hand crank and pulley that powered a fan at the base. Another, the Agan sweeper of 1875, was the first to combine manual suction with rotating brushes. It’s difficult to imagine operating these early vacuums proficiently, let alone with the sort of ease that would justify their purchase. Models of this period seemed to be designed for humans with four arms instead of two.

The most popular version of a manual vacuum cleaner (or pneumatic cleaner, as they were often called) was the Baby Daisy, a big wooden contraption from England that was manufactured starting in 1890. Advertisements for the machine often featured a woman pumping the bellows rod with one arm and holding the suction tube with the other, but this would have been impractical. The Baby Daisy was more realistically operated by two people: one for the bellows and one for sweeping.

After the turn of the century, portable electric vacuum cleaners slowly made their way into newly powered homes. Janitor-inventor James Murray Spangler sold his 1908 invention — credited as the first motorized, portable vacuum cleaner — to William Henry Hoover after Hoover’s wife purchased a model from Spangler to clean her house. Hoover started manufacturing vacuum cleaners and selling them door-to-door so their effectiveness could be demonstrated to potential buyers.

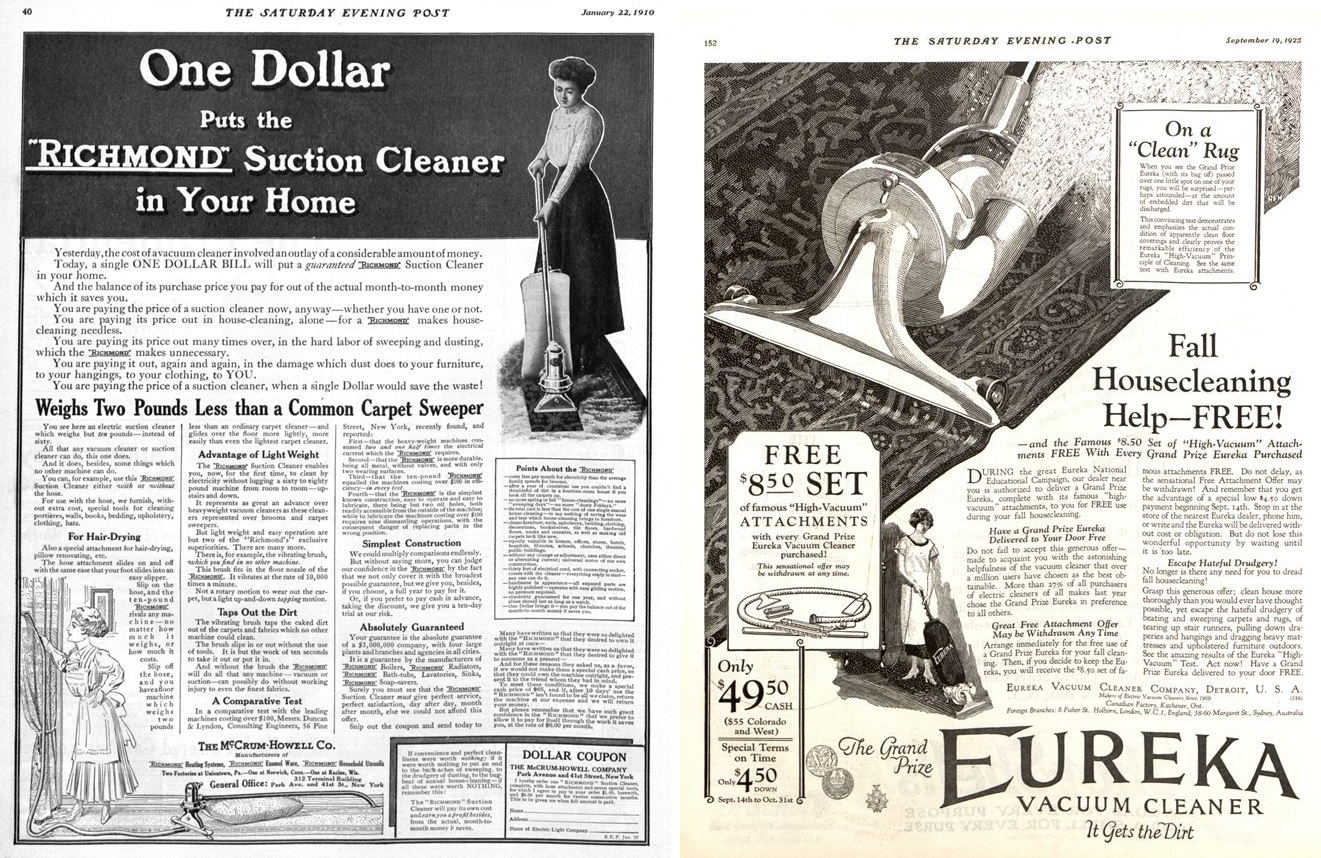

Several companies followed suit, like Eureka, Electric Vacuum Cleaner Co., and Richmond Suction Cleaners, but Hoover came to dominate the market for decades. The first advertisement for an electric suction cleaner in this magazine appeared in 1910, and it promised to deliver the device for only one dollar (about 27 dollars in 2019). Vacuum companies made appeals to women that they could save time and avoid the “drudgery” of sweeping their carpet. While the onslaught of rickety experimental inventions of the past had been a growing pain of the industrial age, these new vacuums were the real deal.

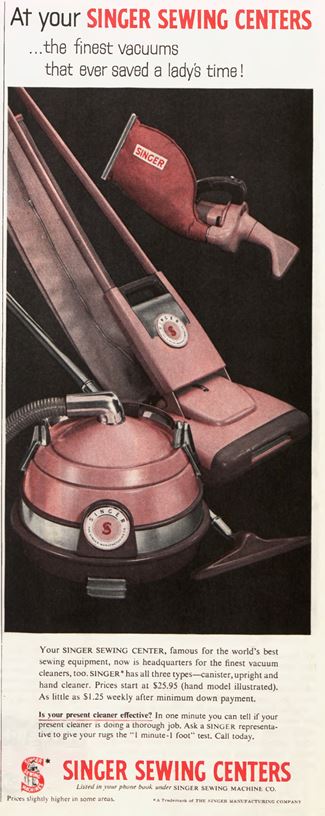

After World War II, the vacuum cleaner became a staple in every home, and trusted brands like Kirby, Hoover, and Bissell were prepared to sell these must-have appliances to newly prosperous households. Decades of innovation yielded vacuum cleaners that were bagless, cordless, and more powerful than ever. Finally, in 2002, a company called iRobot released an autonomous vacuum cleaner that could zip around the house without any help at all. Gone are the stressors of pliant whips and Baby Daisy. These days, you can name your vacuum cleaner any name you’d like, and it will even answer back when you call it.

Featured image: “I Don’t Have to Beat My Rugs,” The Premier Vacuum Cleaner Company, The Saturday Evening Post, March 7, 1914