Celebrate Women Artists: Sarah Stilwell-Weber

Sarah Stilwell-Weber was one of The Saturday Evening Post’s most sought after artists. She even turned down Post editor George Horace Lorimer’s offer to have regularly scheduled pieces because she didn’t want to work on another’s deadline. Between 1904 and 1925, her work was featured on over 60 covers of both the Post and The Country Gentleman (a sister publication of the Post).

A student of famous illustrator Howard Pyle and the Drexel Institute in Philadelphia, one of the top art schools in the country, Stilwell-Weber captured a lighter side of the Victorian Era and the early 20th century in her work. Her young subjects were often on the move, playing games and exploring the world around them. Her mentor, Howard Pyle, told her never to marry, as it would interfere with her artistic life. However, she ignored him and married anyway.

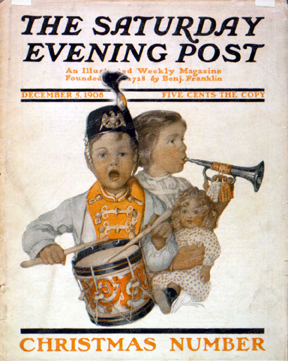

While the children are forming their own marching band, Mom and Dad wonder if Santa takes returns.

Sarah Stilwell-Weber

December 5, 1908

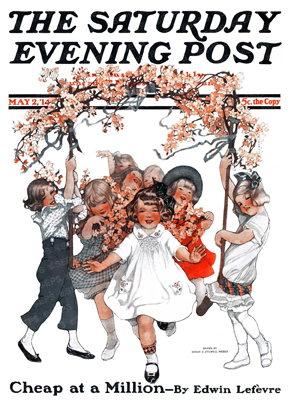

Forget flower crowns, these girls made a flower cape for their May Day parade grand marshal.

Sarah Stilwell-Weber

May 2, 1914

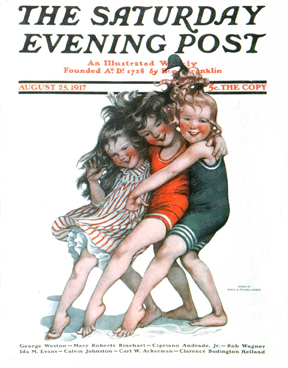

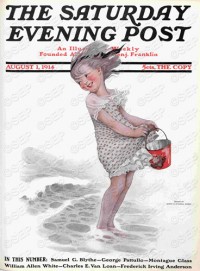

Is there anything better than splashing in waves, soaking up sun, and building sand castles?

Sarah Stilwell-Weber

August 1, 1914

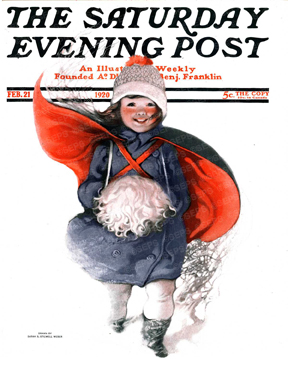

In the early 1900s, the Post covers were printed with a “duotone” two-color process: black and another color, usually red. This process is what makes the umbrella, flowers, and rosy cheeks on this little girl and her doll pop.

Sarah Stilwell-Weber

September 4, 1915

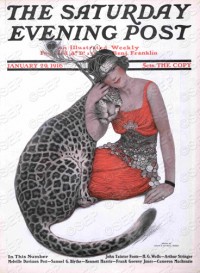

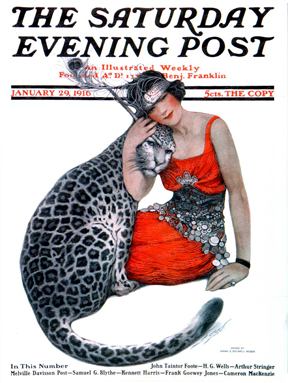

House cats are just too tame. This stylish young woman dared to make a leopard her pet.

Sarah Stilwell-Weber

January 29, 1916

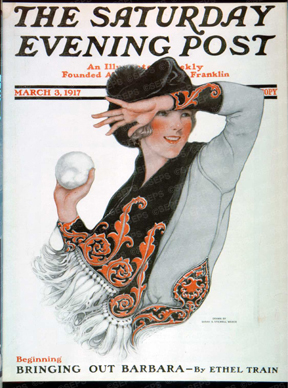

While many Post covers just show portraits of pretty young women, Stilwell-Weber adds life and movement to the traditional medium. This woman joins in the children’s fun after a stray snowball almost hits her.

Sarah Stilwell-Weber

March 3, 1917

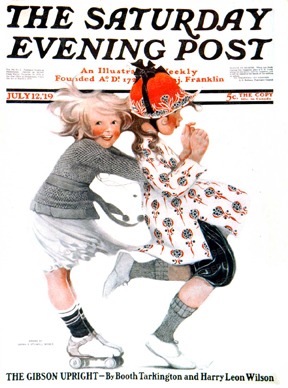

Rolling her way straight into your heart, this tot on wheels is ready for a hug.

Sarah Stilwell-Weber

July 12, 1919

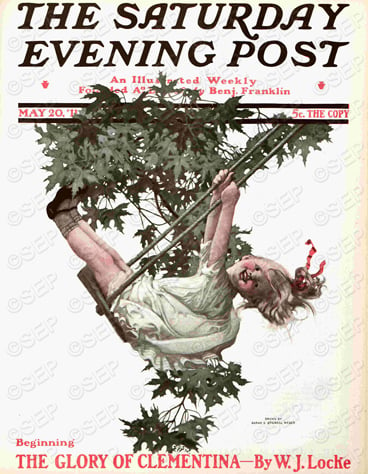

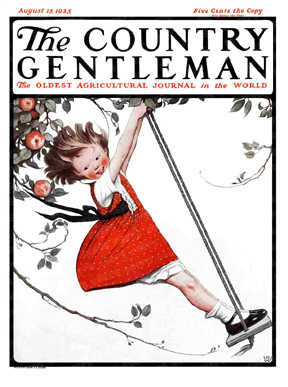

With that mischievous grin, this little one could be gathering momentum to jump or complete a loop-de-loop over the tree branch.

Sarah Stiwell-Weber

August 15, 1925

Sarah Stilwell Weber

Sarah S. Stilwell was born in Concordville, Pennsylvania in 1878. Little is known about Sarah’s early life but her nieces and nephews describe her fondly. “My Aunt Sarah was a unique person with a great deal of imagination which is quite apparent in her work. She was a self-effacing yet positive woman who loved the innocence of little children.”

Sarah was fortunate to attend the Drexel Institute in Philadelphia in 1897, around the time that Howard Pyle was coming on as a full time teacher. Pyle was a well- known illustrationist in his own right, and was known for the innovations that he brought to the field of illustrating. Pyle’s classes quickly became popular, making it difficult to gain entry without strong credentials and fierce determination. In a letter to his friend Edward Penfield, the art editor of Harper’s Bazaar, Pyle wrote:

“I shall make it a requisite that the pupils whom I choose shall possess—first of all, imagination; secondly, artistic ability; thirdly, color and drawing; and I shall probably not accept any who are deficient in any one of these three requisites.”

In the summer of 1899, Sarah-Stilwell was invited to join an exclusive group of students at Chadd’s Ford on the Brandywine. Drexel Institute had managed to raise a thousand dollars for Pyle to fund this special project, with ten one-hundred-dollar scholarships being awarded to only his most talented students. Sarah joined this exclusive group of the best and the brightest in the freedom from the tyranny of conventional and restrictive methods of teaching. They dined, worked and played together, creating a sense of comradery and openness rather than harsh competition. Sarah’s time in this relaxed atmosphere would remain a theme she would foster in the years to come. At the close of Sarah’s first summer session, Pyle’s report read:

“All the students have shown more advance in two months of summer study than they have in a year of ordinary instruction. This, of course, might have been largely due to the fact of the contact of the students with nature and of their free and wholesome life in the open air. They prepared for work at eight o’clock in the morning and they rarely concluded their labors until five or six in the afternoon.”

What Howard Pyle did for his most prized students was literally to launch their career in the New York marketplace. He not only showed them how to improve and refine their talent but he went a step further by introducing them to the market in which their talent could produce a livelihood. And Sarah Stilwell was one of Pyle’s favorite young artist. At the turn of the century, Sarah was one of the first students to move into his Wilmington, Delaware studio at 1305 Franklin Street. There, along with other fine artists as Ethel Franklin Betts, Dorothy Warren, Frank Schoonover, Stanley Arthurs and others, she worked and shared knowledge. Howard Pyle urged Sarah never to marry, as marriage would interfere with the creative life of the artist.

Covers by Sarah Stilwell Weber

Girl with Parasol and Doll

Sarah Stilwell-Weber

September 4, 1915

Three Little Girls at Beach by Sarah Stilwell-Weber

Sarah Stilwell-Weber

August 25, 1917

Girl in Snow

Sarah Stilwell-Weber

February 21, 1920

Sarah did the majority of her cover art for The Saturday Evening Post from 1904 through 1921. Not one to work well under pressure, she resisted the offer by George Horace Lorimer to do regularly scheduled pieces. She preferred having the freedom to work at her own pace and submit items at her leisure, feeling that a deadline might compromise her need to work until she felt personally satisfied with the result. Many of the Brandywine School artists had a flair for capturing grace and detail of the Victorian Era yet not letting decoration and detail overwhelm the subject matter. Sarah was particularly adept at creating movement and flow that gave the impression of coming and going. Her work was not merely a snapshot captured at a point in time. You had the distinct impression that the subject would dance off the page in the next moment.

Sarah Stilwell-Weber’s illustrations graced sixty covers of The Saturday Evening Post and five for The Country Gentleman. Her favorite subjects were of young children while at play, taking you back to a time of simple pleasures. Their youthful enthusiasm and all the movement that goes with their exploration are captured in the expressions on their delight filled faces.

One of Sarah Stilwell-Weber’s last publishing ventures was a children’s book entitled The Musical Tree. Her husband, Herbert, wrote the poems and music, Sarah did the illustrations. She died on April 6, 1939 at her home in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania at the age of sixty-one.

Classic Covers: Women Artists

Let’s face it: The venerable old Saturday Evening Post was never in the forefront of the fight for female equality. Yet, as far back as 1904, some of our finest cover artists were women. This week we share the art of three of these fine illustrators.

Sarah Stilwell-Weber

Swing Up High

Sarah Stilwell-Weber

May 20, 1911

From 1904 to 1921, Sarah Stilwell-Webber (1878-1939) created 60 Saturday Evening Post covers, mostly of women and children. Her paintings of lavishly attired women tended toward the exotic and imaginative, like the lady with the leopard below. Her depictions of children, such as this 1911 cover, delightfully conveyed what fun it is to be a child. These depictions are perhaps why she was also a well-known children’s book illustrator.

Stilwell-Weber studied under the preeminent art instructor of the period, Howard Pyle. In addition to the Post, she illustrated for Country Gentleman, Collier’s, and Harper’s Bazaar. Stilwell-Weber remains a prominent name from the Golden Age of American illustration (1880s-1920s), when American periodicals were rich in artwork that could be mass-produced for the first time.

GALLERY:

Katharine Richardson Wireman

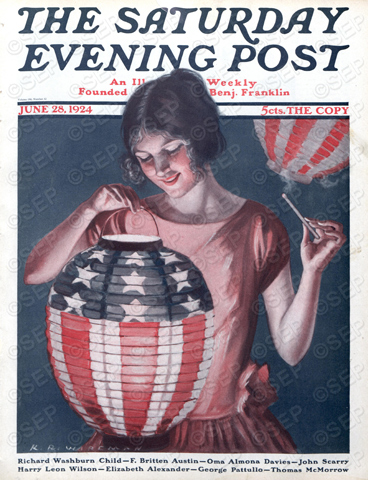

Japanese Lantern

Katharine R. Wireman

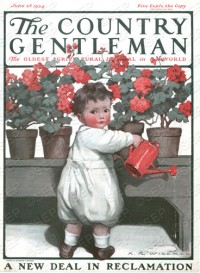

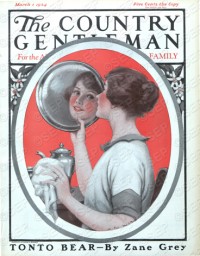

June 28, 1924

Lighting a party lantern for the 1924 Fourth of July celebration provides artist Katharine R. Wireman (1878-1966) an opportunity to work with soft light and shadows. Stilwell-Weber’s contemporary, Wireman created the first of her four Post covers in 1906. (Wiremen also painted 22 covers for sister publication, Country Gentleman.) Her works (below) emphasized carefree moments, and she often depicted her characters with rosy cheeks and joyful dispositions.

Wireman studied at the Drexel Institute under Howard Pyle in 1899. She then moved to Germantown, Pennsylvania, where she and a group of close-knit female artists, including Stilwell-Weber, began their illustration careers.

GALLERY:

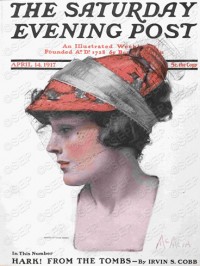

Neysa McMein

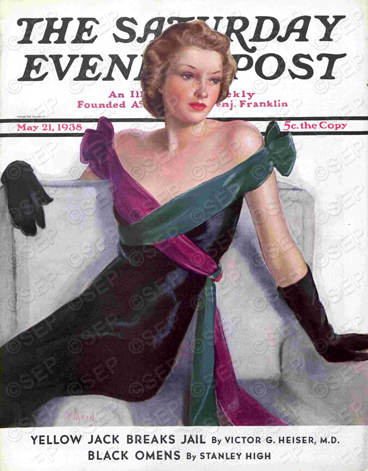

Evening Gown

Neysa McMein

May 21, 1938

By the Roaring ’20s, artist Neysa McMein (1890-1949) was very much a celebrity, mentioned or quoted in magazine articles, fiction, and in advertisements with some regularity. (A 1928 Post article on renowned violinist Jascha Heifetz tells how the musician and his entourage, stuck in a town where nothing for evening entertainment was open, made their way to Heifetz’s room, where he cleared the bed for a dice game and a cheerful shout came from Neysa McMein “whom one does meet in the oddest places,” according to the story.)

McMein was known to entertain other celebrities of the time, such as Irving Berlin, Richard Rodgers, and Dorothy Parker, note Walt and Roger Reed in The Illustrator in America 1880-1980. She lived in an apartment atop Carnegie Hall, writes drama critic David Finkle in an intriguing 2009 Huffington Post article, and she “was known for throwing open her digs to the rich or not-that-rich and famous.

“Furthermore, McMein had a reputation for being a libertine—or, at the very least, a very liberated lady,” writes Finkle. “…There’s an inherent irony here, too. In contrast with her free-spirit life, McMein’s women were the embodiment of innocence [as we see below in a few of her 62 Post covers]. … McMein was defining the American woman for McCall’s, The Saturday Evening Post, and other publications at the same time as chipping away at the image in her daily affairs.”

GALLERY: