Humphrey Bogart’s Dark Side

Originally published August 2, 1952

Humphrey DeForest Bogart, who will be 53 years old come Christmas morning and doesn’t care who knows it, is a whisky-drinking actor who has been hooting at Hollywood and making fun of its pretensions for 22 years. Mr. Bogart’s derision, often acted out with alcoholic capers in night clubs followed by funny quotes in the public prints, is mainly aimed at the popular gospel that under their grease paint, glamorous or menacing, screen players are really fine, home-loving, dish-washing citizens like you and me. In his one bad-man campaign to correct this impression, Bogart has toiled to reestablish the more interesting belief that actors are not necessarily wholesome, meantime making 46 pictures, getting famous, piling up a fortune, having a whale of a good time, and proving to his satisfaction that he is as tough as the gray-faced gunmen he plays on the screen.

Bogart is the kind of guest you would enjoy having in your house — perhaps twice. He will not drink up all your likker [sic]. Indeed he is likely to nurse two Scotches with a moderate dash of soda all evening. He is likely to behave and be darkly charming. But he is also certain to incite a minimum of two fist fights and eight yelling arguments, and exit laughing. Mr. Bogart is a noncatalytic social agent and the precise answer to Dale Carnegie.

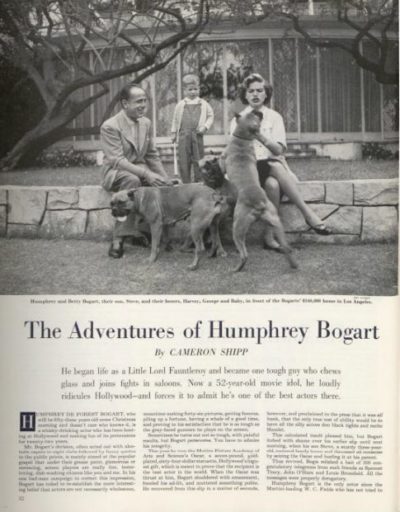

He earns between $300,000 and $400,000 a year today, heads his own production company, owns a famous racing yacht, is one of the last of the great movie stars whose names go above the picture title every time, and has as his wife Lauren Bacall, a fully accredited glamour girl 24 years his junior, brainy enough and tough enough never to take any lip from him.

“He’s a complex guy and hard to live with, but I’m not dazzled anymore. I think I can handle him.”

—Lauren Bacall

Whether Humphrey Bogart could possibly be as tough as he acts in pictures is a matter frequently in dispute. Bogart himself proclaims that he is not physically tough, but that he is mentally a very hard man. He has on several occasions risked destruction in order to hold up his end as a tough guy.

Bogart met the challenge the hard way in Oran when, during the war, he and his then-current wife, Mayo Methot, went over to entertain troops. They fell in, naturally, with the paratroopers, hard, lean, taut-nerved young men who took toughness for granted. Disaster arrived when the paratroopers decided to teach Bogart the trick of rolling with the fall after making a parachute landing. The scene of action was a bistro, and Bogart’s taking-off place was a bar. No parachute. Bogie leaped, dived, lit on his head, and knocked himself out.

In the late ’30s and early ’40s, Bogart would come to Warner Brothers Studio with hangovers so deep they cast shadows. I was there at the time and I marveled not for days, but for years, as the man toiled, letter-perfect before the camera, turning in smooth, underplayed, professional characterizations of cheap villains in many pictures by no means worthy of an actor of talent. During this period he fought with Jack L. Warner for better parts. The Bogart-Warner battles were notable, getting Bogie suspended 11 times, but eventually winning him top-star status and top-star pay, $3,500 a week, along with James Cagney, Edward G. Robinson, and George Raft, villains he had to fight his way past to reach the top. In the midst of these forays and night-long arguments, he had strength enough to caper.

Once, producer Mark Hellinger took him to a Sunset Strip gambling establishment. The man at the peephole immediately locked the door. “Bogart is barred. Creates disturbances,” he said.

“This is the new Bogart,” Hellinger promised. “The sober Bogart. I vouch for him, on my honor.”

The peephole man bugged a big eye.

“Mr. Hellinger,” he said quietly. “Mr. Hellinger, look behind you.”

Sid Avery

Bogart was fighting with two parking-lot attendants.

“You know he did that just to cross me up,” Hellinger always insisted.

Mrs. Bogart, whom he calls “Betty,” her real name, admits that she is often terrified by the Bogart temper, a white-faced anger which cannot be appeased. But what mystifies her is this: Mrs. May Smith, his cook, has been with him for 16 years. Aurellio Salazar, his gardener, for 15; and Mrs. Kathleen Sloan, his secretary, for 8.

“Wives come and go, but they stay,” says Betty, vastly puzzled. “He’s a complex guy and hard to live with, but I’m not dazzled anymore. I think I can handle him.”

Everybody else in Hollywood thinks she can too.

Dave Chasen, who throws Bogie out of his restaurant once or twice a month for old times’ sake, is the author of two sentences which come close to summing the man up. “He’s a hell of a guy until 11:30,” says Dave. “The only trouble with Bogie is, he thinks he’s Bogart.”

—“The Adventures of Humphrey Bogart” by Cameron Shipp,

August 2, 1952

This article is featured in the May/June 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.