Considering History: Vitriol and Violence, Radical Activism, and the Suffrage Movement

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

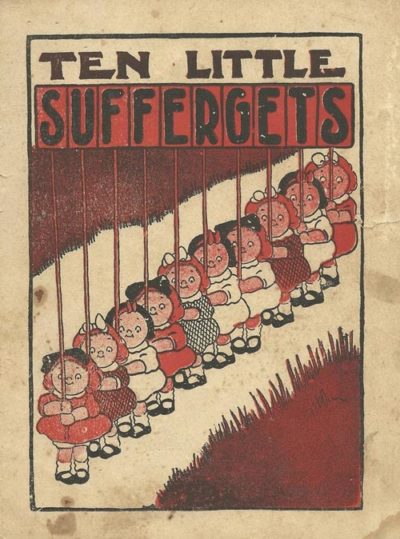

The early-20th-century children’s book Ten Little Suffergets (c.1910-1915) literally and figuratively illustrates the vitriol and violence often directed at the women’s suffrage movement and its participants. Based on the racist nursey rhyme “Ten Little Indians,” the book portrays suffrage activists as a group of spoiled young girls, carrying signs demanding such changes as “Cake Every Day,” “No More Spanking,” and “Down with Teachers” alongside “Equal Rights.” One by one the “suffergets” are either distracted by frivolous pursuits and abandon the cause or are violently removed from the march (such as by an angry father figure). The concluding image is of the final girl’s abandoned “dolly” (looking quite like the girl herself) with a cracked and broken head.

It’s possible in hindsight to see a now broadly accepted cause like women’s suffrage as being widely accepted and shared, as a significant political change that took time to achieve but without the kinds of hostile responses other such social movements have received. But in fact, across its more than half a century of existence, the American suffrage movement was quite the opposite: a profoundly radical and progressive idea that was subjected relentlessly to both rhetorical and actual attacks. Remembering those attacks always helps us consider the consistent courage of suffrage activists in facing such harassment and arguing for their cause, often in the most public places and ways.

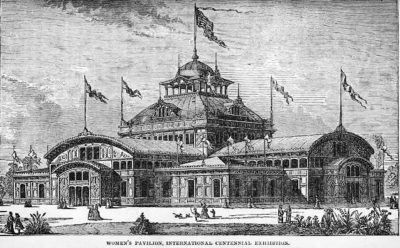

The July 4, 1876 protest at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia was one such occasion. For the first time at a World’s Fair, the Centennial included a separate Women’s Pavilion, a space in which to celebrate and share women’s identities, art and culture, and voices. Yet this impressive step was not without its limits, and one was the near-complete absence of any social or political issues — including the era’s most prominent such issue, suffrage — from the pavilion. Indeed, focusing more on domestic arts and crafts and housework, the Women’s Pavilion could be said to reinforce some of the most prominent arguments against women’s participation in the public and political spheres.

A group of suffrage activists, representing the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), decided to highlight this exclusion and their cause at the Centennial’s most public occasion, the July 4th celebration. Led by Susan B. Anthony, the group erected a stage of their own not far from the celebration’s official platform, and there read aloud a “Declaration of Rights of the Women of the United States” (a revision and extension of the declaration produced at the 1848 Seneca Falls Woman’s Rights Convention). Before doing so, Anthony made clear the group’s willingness to confront their fellow Americans in this most public space, noting, “While the nation is buoyant with patriotism, and all hearts are attuned to praise, it is with sorrow we come to strike the one discordant note, on this 100th anniversary of our country’s birth.” Yet she added, “Our faith is firm and unwavering in the broad principles of human rights proclaimed in 1776, not only as abstract truths but as the cornerstones of a republic.”

Anthony, the NWSA, and their many colleagues continued to strike their discordant note and fight for the extension of those rights for the next four decades. Another very public moment of radical activism, and one met with particularly violent response, was the March 1913 Women’s Suffrage Parade. Held in Washington, DC, on the day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration, the parade represented the largest gathering of suffrage activists and allies in American history, with more than 5,000 participants marching down Pennsylvania Avenue.

The marchers were met with sustained hostility, not only from many in the crowd but also from at least some of the police officers tasked to protect the parade. Hundreds of marchers were seriously injured; according to one eyewitness testimony quoted in The Washington Post, two ambulances “came and went constantly for six hours, always impeded and at times actually opposed, so that doctor and driver literally had to fight their way to give succor to the injured.” Yet the marchers, led by prominent activist Alice Paul and attorney Inez Milholland (riding a white horse), persevered, completing their planned route from the Capitol to the Treasury building, and drew national attention to both their cause and the violent attacks upon it.

The parade also featured an internal discordant note that produced one more moment of radical courage. The organizers intended the march to be segregated, with a separate cohort of African-American suffrage activists bringing up the rear. The pioneering journalist, anti-lynching crusader, and women’s rights activist Ida B. Wells asked if she could march with the Illinois delegation in the main march, and was initially turned down. Yet Wells did not accept this answer and, with the aid of sympathetic allies, defied this racist division and joined the Illinois delegation as the march began. In so doing, Wells embodied one more moment of radical persistence in the face of contempt and exclusion, a historical lesson that the American suffrage movement offers consistently and crucially.