On the Sidelines, Mussolini Awaits His Opportunity

( via Wikimedia Commons)

You may have seen the photos of Benito Mussolini’s messy demise. The photos show the corpse of Italy’s ex-dictator, shot, beaten, and kicked, hanging upside down from the roof of a gas station. Seeing the brutality of his death, you get a sense of how fiercely the Italians hated the man who had dragged their country into a war that brought only poverty, disgrace, and death to their land.

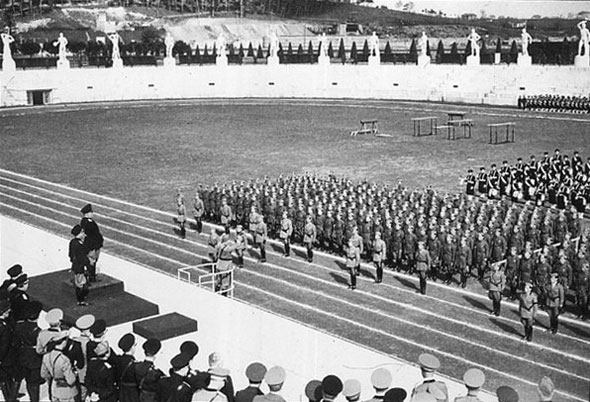

Once Mussolini had enjoyed broad support in Italy. He presented himself as the savior of the country, promoting fascism as the solution for the country’s problems. He inspired young Italians to join forces, donning the black shirts of the fascist party members. He also inspired a young Austrian named Adolf Hitler, who looked up to Mussolini as a role model.

But Hitler was a fanatic. Mussolini was an opportunist. And nothing illustrated his opportunism better than his actions in 1939. In May of that year, he and Hitler signed an alliance in which they pledged to come to each other’s aid in the event of war.

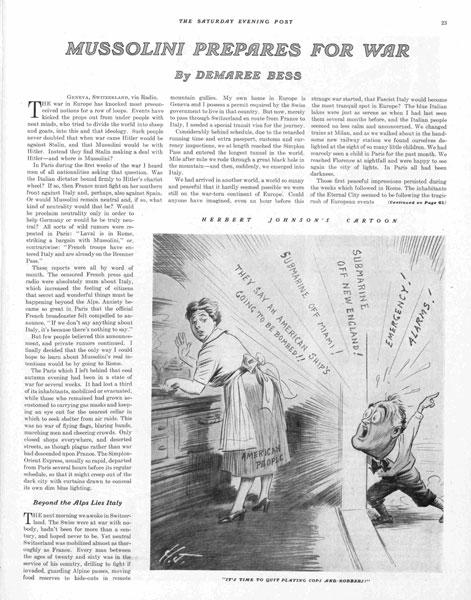

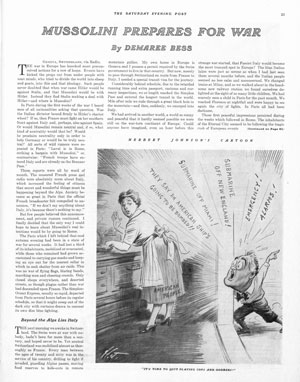

Furthermore, the agreement “stipulated that neither of the parties would take action within the next three years [to] cause war in the West,” wrote Post correspondent Demaree Bess. [Read the entire article “Mussolini Prepares for War” from the Nov. 18, 1939 issue of the Post here.] Mussolini needed that delay. His advisors had told him Italy wouldn’t be ready to launch a war before 1942.

Not surprisingly, Hitler ignored this clause in the agreement when, just four months later, he declared war on Poland. As his army launched its blitzkrieg, the world looked to his ally Mussolini. What would Il Duce (the Italians title for “the leader) do now?

Bess was hearing all sorts of wild rumors of possible alliances and confrontations—an alliance between France and Italy, war between France and Italy, even an attack from Germany. “I finally decided that the only way I could hope to learn about Mussolini’s real intentions would be by going to Rome,” he wrote.

Bess left a darkened, huddled Paris that anticipated German bombers at any moment. Traveling south, he found Italy sunny and peaceful. “As we walked about in the handsome new [Milan] railway station, we found ourselves delighted at the sight of so many little children. We had scarcely seen a child in Paris for the past month. We reached Florence at nightfall and were happy to see again the city of lights.”

The Italians were happy again with il Duce, then regarded as a man of peace. He was making no overt moves to drag Italy into Hitler’s crusade against France and England. “[Italy] seemed to be in a position to stay neutral as long as she liked — and to make money trading with the belligerents,” Bess wrote. Yet he became convinced that Mussolini had no intention of staying out of the war a moment longer than necessary. “He is standing on the side line now, watching how things go, but he isn’t idle. … He is preparing for war.”

Il Duce had set the country on the road to war many years earlier. “He has raised a whole generation of Italian youth in the faith that they should live dangerously, that pacifism is a vice,” Bess wrote. And now, though Italy was still neutral, Mussolini’s government was starting to ration food for civilians and stockpile it for the army.

Mussolini’s refusal to join Germany’s war prompted some to believe he was reconsidering his alliance with Hitler, which had always been “extremely unpopular with Italians,” Bess wrote. “Italians naturally dislike Germans. The two races don’t get along well together. Germans are impatient with the easygoing temperament of Italians and don’t conceal their impatience. Italians resent German assumptions of superiority merely because they are more efficient.”

For now, the Germans weren’t pressuring Italy to join their fight. In fact, Hitler found Italian neutrality useful. According to Bess, it allowed Mussolini to play a peacemaker who suggested there could be a “settlement of the war in the West, thus enabling Hitler to pose before his own people as a reasonable man who didn’t want to fight Britain and France.”

France and Great Britain were also satisfied with Italian neutrality, since it enabled them to maintain their control of the Mediterranean Sea without having to engage the Italian fleet.

Mussolini was under no pressure to commit Italy to the world war. “He foresaw that no pressure from either side could or would compel him to enter this war until he was ready to move,” Bess wrote. “Germany’s air force might destroy Italian cities, but what could Germany gain from that?”

Mussolini would remain neutral for as long as it was profitable. But Hitler’s swift victory over France led Mussolini to weigh the profits from war versus peace. If he remained out of the fight, his country might continue its gradual rise in prosperity. And he might take up the offer of trading concession in Africa that Great Britain and France would grant if Italy remained neutral.

But if Italy entered the fight, it might be able to share in Germany’s looting of conquered France. All he needed, Mussolini told his military chief, was to lose a few thousand Italian soldiers in the war to earn a share of the spoils at the victor’s table. And then Italy could simply seize whatever African colonies had belonged to the Allies.

Above all, Mussolini became trapped by his own bravado. Having posed as a modern-day Caesar, he needed to prove the might of his country’s forces.

On June 10, 1940, he committed Italy to the war. He sent his soldiers into France, prompting President Roosevelt to comment, “The hand that held the dagger has struck it into the back of its neighbor.”

The decision began a long, sharp decline in the fortunes of both Italy, and Mussolini, who suffered the consequences in Milan at the hands of an enraged mob.

Step into 1939 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 75 years ago: