Impeachment: What We Know Will Happen and What We Don’t

Throughout our nation’s history, the House of Representatives has begun impeachment inquiries over 60 times. You would think that, by now, the process would be better organized. But many of the steps can take unexpected turns.

As Congress moves ahead on the current impeachment inquiry of President Trump, the path becomes more hazy the farther we peer into the future. Here is a quick overview of where things might go from here.

The House of Representatives

We Do Know

- The House Committee on the Judiciary is holding hearings on the resolution to impeach the president. (The Committee oversees the administration of justice through federal courts and agencies.)

- If the impeachment hearings proceed at the pace as Clinton’s and Nixon’s investigations, according to Time magazine, they will be over by March 23.

- When the committee, which is made up of 24 Democrats and 17 Republicans, concludes its hearings, it will vote on impeachment. If approved by a simple majority of members, the inquiry will pass to a full House vote. If not, the matter will be dropped.

- In the House, it will be voted on by the entire assembly. If passed by a simple majority of 435 members, it will move on to the Senate.

We Don’t Know

- What the articles of impeachment will be. If there is more than one article, Judiciary Committee members will vote on each article separately. We don’t know which article(s) will be approved for full House consideration. (When the House investigated President Nixon, it drew up three articles. Nixon resigned between the Judiciary Committee’s vote for impeachment and the House vote.)

- How the House will vote. Most members of House majority, which consists of 235 Democrats, are in favor of the inquiry. But voting for impeachment itself is another matter. Of the 60 inquiries begun in the House, only a third have resulted in impeachment (15 federal judges, a cabinet secretary, a senator, and two presidents.)

The Senate

We Do Know

- If it acts on the House vote, the Senate will become the High Court of Impeachment, presided over by the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court John Roberts.

- House members, called Managers, usually from the Judiciary Committee, will appear before the Senate to act as the prosecution, presenting testimony and evidence to support conviction.

- The president will probably not be present, but will be represented by counsel.

- Once the Managers have presented their case, the Senate will vote. If at least two thirds of the senators (67) vote for conviction, the president will be removed from office.

- There will be no subsequent trials based on the Congressional charges.

- The president cannot issue a pardon for himself in the case. Nor can he appeal his conviction to the Supreme Court.

We Don’t Know

- Which way the Senate will vote. The president’s party now holds the majority. If all 45 Democrats voted in favor of conviction, it would still require 20 additional senators (Republican or Independent) to vote with them for the president to be convicted. Party loyalty has, up to now, been strong, but Republicans have voted with Democrats before on these matters. In 1998, 28 Republicans voted against the perjury charge against President Clinton, and 81 voted against the abuse of power charge.

- If the Senate will hold a trial at all. Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said, “I would have no choice but to take it up, based on a Senate rule on impeachment.” However, as Prof. Bob Bauer, a former counsel to President Obama has written, the Constitution gives the Senate to sole right to try the president but doesn’t require it to carry out this function. “Senate leadership can seek to have the rules ‘reinterpreted’ at any time,” writes Bauer. “Senate leadership can seek to have the rules “reinterpreted’ at any time by the device of seeking a ruling of the chair on the question, and avoiding a formal revision of the rule that would require supermajority (67%) approval.”

- How the Senate will conduct the trial. It can give the Managers too little time to present their case. Or it can adjourn for more than three days, which would terminate the trial. But a Senate resolution to adjourn would require a concurrent resolution by the House, which probably wouldn’t want the trial halted.

- How the actions of the president will be interpreted. The Constitution allows Congress to remove the president if he has committed “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.” However, the authors of the Constitution didn’t specify what those crimes and misdemeanors might be. The Senate’s own guide to the impeachment process says the question is far from settled. The lawmakers’ interpretation, it says, falls between “those who view impeachment as a response to an official’s perceived violation of the public trust against those who regard impeachment as being limited to indictable offenses.”

Featured image: Shutterstock

What You Probably Forgot about the Clinton Impeachment

It’s only happened once before in United States history: a sitting president undergoes an impeachment trial in the Senate. The first time Andrew Johnson was tried in 1868 over his dismissal of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton; although he was impeached by the House, he was spared by a single vote in the Senate. A similar pattern played out in 1998, when President Bill Clinton faced two charges that emerged in the wake of a lawsuit filed by Paula Jones.

Paula Jones interview from ABC’s Primetime Live in 1994.

Jones filed her lawsuit in 1994, two years after Clinton took office for his first term. The suit alleged sexual harassment on the part of Clinton during a hotel room meeting between the two in 1991. While building their case, lawyers representing Jones investigated rumors surrounding Clinton’s relationship with White House intern Monica Lewinsky. These lines of inquiry occurred concurrent with the Whitewater real estate investigation into Clinton’s business dealings that was being headed by special counsel Kenneth Starr.

When Clinton gave his statement for his deposition for the Jones case in January of 1998, he was questioned about his relationship with Lewinsky. Clinton stated under oath that he had no relationship with Lewinsky outside of professional contact, going so far as to state that he was never even alone with her. This statement was contradicted by Lewinsky’s own personal account of events; in phone conversations with co-worker Linda Tripp, Lewinsky offered many details about her relationship with Clinton, including gifts and sexual encounters. Unknown to Lewinsky, Tripp regularly recorded those phone conversations and eventually turned the recordings over to Starr. Furthermore, the conversations provided information that Clinton had asked Lewinsky to conceal the relationship, and that Lewinsky, in turn, had asked Tripp to deny her knowledge of the relationship if called to testify.

Starr decided that Clinton’s actions constituted perjury, and he backed this up with other collected evidence, including Lewinsky’s hard drive and emails. Starr compiled his findings in the document that became popularly known as the “Starr Report.” The report was sent to Congress and posted online.

Shortly after the November 1998 election, the Republican-controlled House of Representatives entered impeachment proceedings against Clinton. In House Resolution 611, Clinton was impeached on one count of perjury and another of obstruction of justice; both counts stemmed from the Jones deposition. A second article of perjury and one of abuse of power failed to receive majority votes in the House.

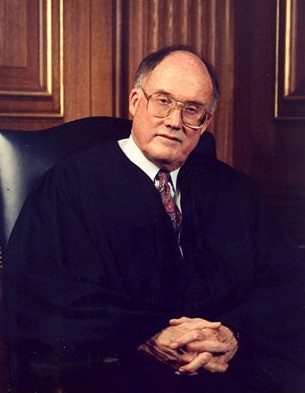

The Senate trial began on January 7, 1999. Then-Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, William Rehnquist, presided over the trial; what was functionally the prosecution side of the case was handled by 13 House Republicans, including current Arkansas governor Asa Hutchison and current South Carolina senator Lindsey Graham. Clinton was defended by lawyer Cheryl Mills and a team that included future Obama White House Counsel Gregory B. Craig. The proceedings ran until closed-door deliberations began on February 9th.

Ending deliberations on February 12th, the Senate put it to a vote. With 67 votes required to convict the president and remove him from office, the Senate voted to acquit. The totals came in at 45-55 on the perjury charge, and 50-50 on obstruction. Every one of the 45 Senate Democrats voted not guilty on both charges. Clinton remained in office, serving out the rest of his second term. In April of 1999, he was cited for contempt of court for lying in the Jones deposition; the president ultimately agreed to having his license to practice law in his home state of Arkansas suspended for five years. As for the civil suit brought by Paula Jones, Clinton settled in November of 1998, prior to the impeachment proceedings, for $850,000.

Though impeachment has been an increasingly common topic of discussion of late, it’s definitely not a speedy process. It’s complicated, and it should be, as it’s not something that the nation wants to enter lightly. That said, Congress has historically wielded that power wisely, and it’s likely that the men and women of both houses are fully aware of the import that initiating such a process carries for the country.

Feature Image credit: White House photograph of President Bill Clinton and Monica Lewinsky. (White House photo)

A Quick Guide to Impeachment

February 24 is the anniversary of President Andrew Johnson’s impeachment in 1868. Many Americans are more familiar with Bill Clinton’s impeachment than with Johnson’s, but our un-scientific survey revealed that even well-informed people are a little fuzzy on what impeachment actually is and how it works, exactly. Here’s a quick overview:

What Is Impeachment?

Impeachment means indictment — specifically, a charge of serious misconduct against a high official by a legislature. Article II of the Constitution says the president, vice president, and “civil officers of the United States” can be impeached. Whether or not members of Congress are included in “civil officers” is still debated.

Two presidents have been impeached, but neither were convicted.

What Exactly Is an Impeachable Offense?

The Constitution defines impeachable offenses as “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.” But these are broad, debatable terms.

Constitutional lawyers define “high crimes and misdemeanors” as anything that breaks existing law, is an abuse of power, or, as Alexander Hamilton wrote, is “the abuse or violation of some public trust.”

Gerald R. Ford gave a working definition of an impeachable offense: “whatever a majority of the House of Representatives considers it to be at a given moment.”

In practice, articles of impeachment have cited acts that exceed the constitutional limits of the powers of an office, behavior at odds with the function and purpose of an office, or use of an office for improper purposes or personal gain.

How Does the Impeachment Process Work?

The House Indicts

The House of Representatives begins the impeachment process. The House Judiciary Committee starts the process by sending to the House articles of impeachment, a resolution that spells out why impeachment is justified. The House then debates and votes on that resolution. An official is impeached only if two-thirds of the House approves the articles of impeachment. But the House can’t take action beyond this vote, and the impeached official isn’t removed from office.

The Senate Convicts and Expels

The impeached official now faces a trial in the Senate. The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court acts as judge in the proceedings, and the Senators are the jury. After hearing the evidence, the Senators meet privately and discuss their verdict. If two-thirds of the Senators agree, the impeached official will be convicted and removed from office. The Senate may even pass a resolution forbidding the official from ever again holding public office.

Who Has Been Impeached?

- Moves toward impeachment were made against John Tyler (1841-1845) when Congress resented his use of the presidential veto, but the resolution against him failed.

- Andrew Johnson (1865-1869) was impeached for his lenient attitude toward the defeated Confederate states, which allowed many of its pre-war officials to return to office. The triggering event was his dismissal of Edwin Stanton, Lincoln’s Secretary of War, who opposed Johnson’s policies. Johnson was impeached by the House, tried in the Senate, and acquitted by a single vote.

- Congress was debating the impeachment of Richard Nixon (1969-1974) over the Watergate scandal when he resigned.

- Bill Clinton (1993-2001) was charged in 1998 with perjury and obstruction of justice in the investigation of his affair with a White House intern. He was impeached by the House but acquitted by the Senate.

Extra Credit: The First Impeachment Hearings

Americans are naturally troubled by the prospect of a presidential impeachment. In March 1868, when President Andrew Johnson was being impeached, the Post reassured readers that impeachment was a necessary, vital part of our democratic process. It contrasted, perhaps unfairly, the orderly process of trying the U.S. president to the armed turmoil shaking the governments of Mexico and Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic). But it expressed ultimate faith in the American people and their Constitution.

Not Mexico

For a short period dining the first excitement of the Impeachment, we began to doubt whether we were living in the United States or in Mexico — but the sober second thought of the people soon rectified the blunders of foolish partisans.

The House of Representatives has an undoubted right to impeach the President, or the Acting President, whichever his true position may be. Its members have the right to judge for themselves of the propriety of their course.

The Senate has the undoubted right — nay more it is its duty — to sit in judgment on the charges that are brought by the House — and acquit, or find guilty, as a majority of two-thirds sees proper. If the Senate finds President Johnson guilty of high crimes and misdemeanors, he must, and doubtless will, without any hesitation, conform to that judgment.

It may be said, that both House and Senate may act in the spirit of mere partisans, and alike accuse and condemn without sufficient evidence. Undoubtedly they may. But the Constitution supposes that they will not. If they do act as mere partisans, their punishment will be the rebuke of the people.

In the Autumn, the Republican party goes before the People — with its candidate for the Presidency, its candidates for Congress. The fair or unfair manner in which the Impeachment trial has been conducted, will be an important element in the canvass. In fact, the Impeachers themselves will be then put on their trial, before the great Jury of the People of the United States.

And thus there is no need of soldiers and bayonets — no need to make these United States a Mexico or St. Domingo. Ultimately all these vexed questions must be decided by the people. Ultimately the will of the people will prevail. Both the contending parties profess to desire this. Let all then be done peaceably, legally, and in order. It will be no recommendation to either party, in the great Presidential and Congressional campaign of the coming Autumn, that it has needlessly broken the peace, and plunged the Union into civil strife.

Editorial, March 7, 1868

Featured image: Impeachment ticket for President Johnson (U.S. Senate)