Who Gets to See the President’s Tax Returns

On April 3, 2019, House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Richard Neal wrote to the IRS, asking to review President Trump’s personal and business tax returns for the purpose of verifying whether IRS is auditing the President in a fair and impartial manner. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, who oversees the IRS, rejected the request on May 6. At this point, the requesting tax committee may choose to seek legislative enforcement in a federal court. Regardless of the outcome, it’s likely that the process will be a long and legally complex one. And it will probably all hang on a small provision in a law from 1924.

Section 601 of the Revenue Act of 1924 enables Congress to subpoena the tax returns of people and businesses. Called the “committee access” provision, it can be invoked by any of three tax committees: The House Ways and Means Committee, the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT), and the Senate Finance Committee.

The Treasury Department provides the requested tax information, but not without some provisions. The information is shared only in closed sessions and only so long as it serves a “legislative purpose.” Committee members are prohibited by federal law from divulging what they see to the public. However, if members of these committees believe it necessary, they can share the information with other committees.

Not only does Section 601 give legislators the right to look at what has long been held as highly confidential, it further declares that the Treasury Department can’t limit what it provides to the committee.

The origins of Section 601 lie in a feud between a senator and a Treasury secretary, but it was ultimately enacted to preserve the government’s system of checks and balances.

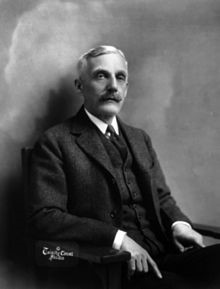

In 1924, Michigan Senator James Couzens opposed a restructured tax code proposed by Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon. Though both men were wealthy, Couzens didn’t agree with Mellon’s plan to reduce the tax rate on top incomes. Couzens made his case in a letter to the newspapers, citing his own experiences as a taxpayer. He claimed to have paid $8 million in taxes; he would have paid more but he’d invested in tax-exempt securities.

Mellon responded, defending the tax cut. He supported his argument by referring to some of the personal tax information Couzens had provided in his letter.

Couzens fired back, requesting to see which securities Mellon owned and how the law might personally benefit him. Forgetting the tax information he had provided in his letter, Couzens and his supporters believed Mellon had looked at Couzens’ tax return before writing his response.

Since America had entered World War I in 1917, the Bureau of Internal Revenue (the BIR, as the IRS was formerly called) had accumulated a backlog of audits and other paperwork, which made the bureau unresponsive to taxpayers. Couzens suggested that the backlog was a fabrication by Mellon to hide his own tax dodging.

All this took place when reforming fever was running high in Washington. Congress had recently conducted several investigations into the Harding administration, including the sale of government oil reserves at Teapot Dome, Wyoming.

In response to the scandal, Congress created a committee of senators and representatives to oversee tax policy, the Joint Committee on Taxation. Ultimately, Couzens was named its director. To help him understand the complex tax laws of the BIR, he personally hired Francis Heney as the committee’s legal counsel. Heney had a reputation as a reformer, and his inclusion made the JCT appear more interested in prosecution than investigation.

Then President Coolidge intervened. He publicly called for an end to the investigation into the BIR. Congress’s intrusion, he said, was setting the country on a dangerous path. It was replacing a government of laws with “a government of lawlessness.”

Legislators might have been unsure whether Mellon had misused his office as Treasury secretary in his feud with Couzens, but they resented the president’s intrusion into their operation.

And then came a new development. The BIR — which Couzens was currently investigating — announced it was investigating a long-ago tax claim of Couzens’ that was just about to become too old for enforcement.

Congress was now convinced that the BIR was targeting Couzens and, potentially, all legislators for overstepping their powers.

The legislators focused on the fact that Congress had oversight of every department of the government except the Treasury, which answered only to the president. The BIR operated with little visibility. Only 15 percent of the BIR’s income tax rulings had ever been published.

Congress demanded access to tax records, citing the need to see how tax laws were being interpreted and to investigate violations of tax laws and any crimes involving revenue. Without this provision, any illegality in the Treasury or the executive branch could remain hidden forever.

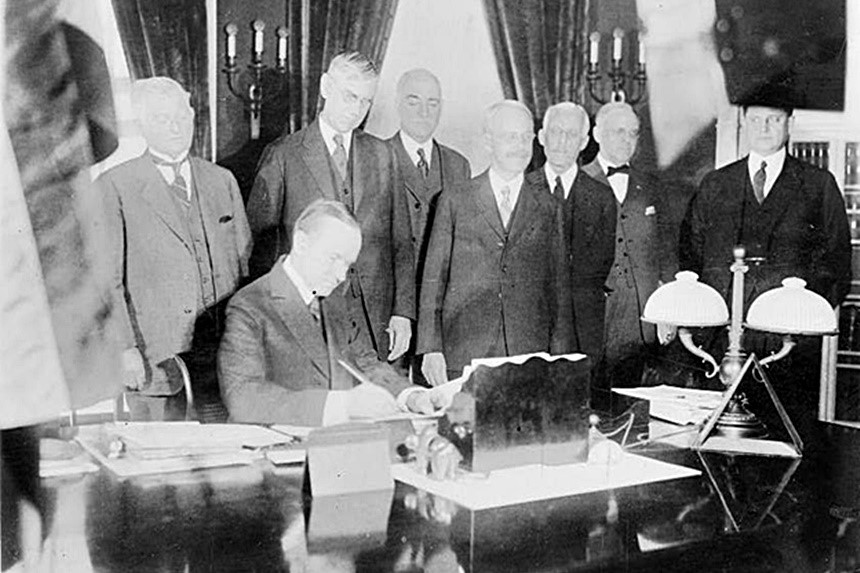

Over the strong objections of President Coolidge and Secretary Mellon, Section 601 was included in the Revenue Act of 1924.

It will be interesting to see if its age, obscurity, or relevance will affect the power of the committee access provision in the current controversy.

Featured image: Library of Congress / Shutterstock