6 Things You Didn’t Know About the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office

America prides itself on ingenuity. In 1790, we started making it official. 230 year ago today, the first patent was issued in the United States. Over time, the power of patent has moved from a group of three people and through multiple departments before finally settling in the United States Patent and Trademark Office in 1975. Despite the pervasive nature of invention in our society, some citizens don’t even know what a patent is. Here’s a look at that answer, what the first patent was, and how patents might evolve in the future.

1. What is a Patent Anyway?

In simplest terms, a patent is an idea that you own, also called intellectual property. When someone secures a patent, they are the legal owner of the idea described and can prevent others from profiting from or manufacturing the object of the patent for a period of time. In exchange, the patent holder is required to submit public documentation detailing how the idea/product/etc. works.

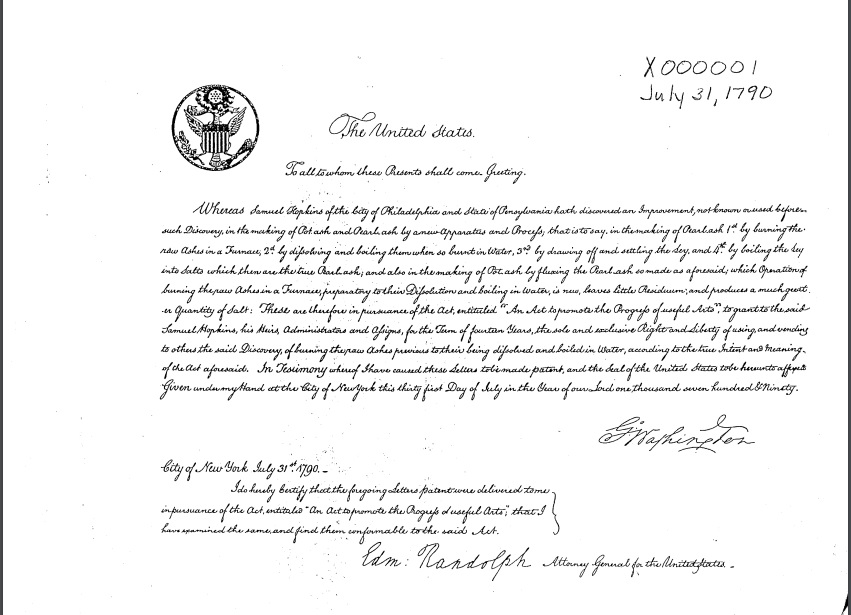

Patents in the United States are covered in the Constitution in Article I, Section 8, Clause 8. The Clause reads that “[The United States Congress shall have power] To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.” All subsequent U.S. patent and copyright laws are built on this statement, which was first discussed by Charles Pinckney and James Madison in 1787. The Clause became law with the ratification of the Constitution. Title 35 of the United States Code sets up how patent law works.

2. Early Patents Got Approved by Three People

The Patent Act of 1790 added more detail to how the patent process worked. Three people were given the power to refuse or grant patents: the Attorney General, the Secretary of War, and the Secretary of State. An applicant could get a patent if two of the three voted yes. Determinations at the time were based on the novelty of the idea/item/etc. and if the subject of the application was, in the words of the Act, “sufficiently useful and important”.

3. The First Patent

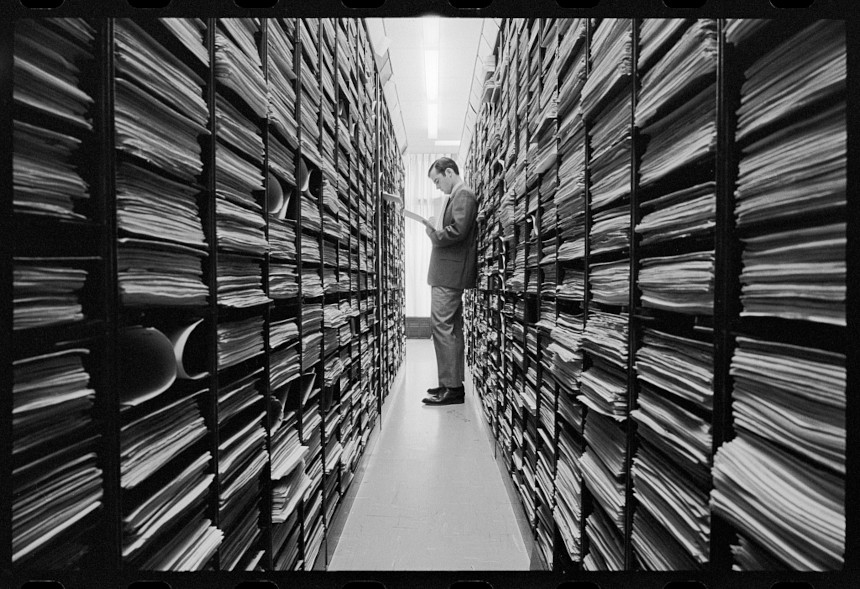

4. The Fires

While much of the business of the Patent Office has run smoothly on an ideological level, practical challenges have sometimes appeared. The sheer volume of submissions means that backlogs are a problem, necessitating the opening of satellite sites to clear all of the potential patents waiting to be reviewed. There have also been some incredibly damaging fires that affected the office.

In 1836, U.S. Patent Office at Blodget’s Hotel in Washington, D.C. burned; the 10,000 patents on site were reduced to ash. Ironically, it had been one of the few buildings in the area not burned by the British during the War of 1812. After the fire, new procedures were put in place, and the Patent Act of 1836 made the Patent Office an individual organization within the Department of State.

A supposedly fireproof new building for the office was completed in 1864, but it wound up burning as well in 1877. A few hundred thousand patent drawings were destroyed by fire or water, but the loss wasn’t considered as serious; due to the procedural changes made after the 1836 blaze, copies of the drawings and documents were now kept in separate locations to ensure their overall survival.

5. The Different Departments

The Patent Office has the distinction of, well, moving around a lot. Initially, after the 1790 Act, the office was housed under the Department of State. It would shift over to the Department of Interior until 1925, at which time it moved to its current home in the Department of Commerce. In 1975, the office was reorganized as the United States Patent and Trademark Office, with headquarters in Alexandria, Virginia. There are now four satellite office locations: they’re in Dallas, Texas; Denver, Colorado; Detroit, Michigan; and San Jose, California.

6. How to Apply for One Today

Roadmap to Filing a Patent Application (Uploaded to YouTube by USPTOvideo)

Everything that you need to know about applying for a patent is located on this page of the USPTO.gov site. The first step is to search the extensive database at the site to ensure that you aren’t submitting a patent that already exists. Effective August 1, 2020, the filing fee will go up to $532 to file for a patent. The USPTO is unique among government offices as it’s totally paid for by filing fees, rather than tax dollars; for years, 10 percent of the USPTO funds were funneled into the federal budget, but that practice stopped being a regular occurrence during the George W. Bush administration.

Featured image: Mark Van Scyoc / Shutterstock

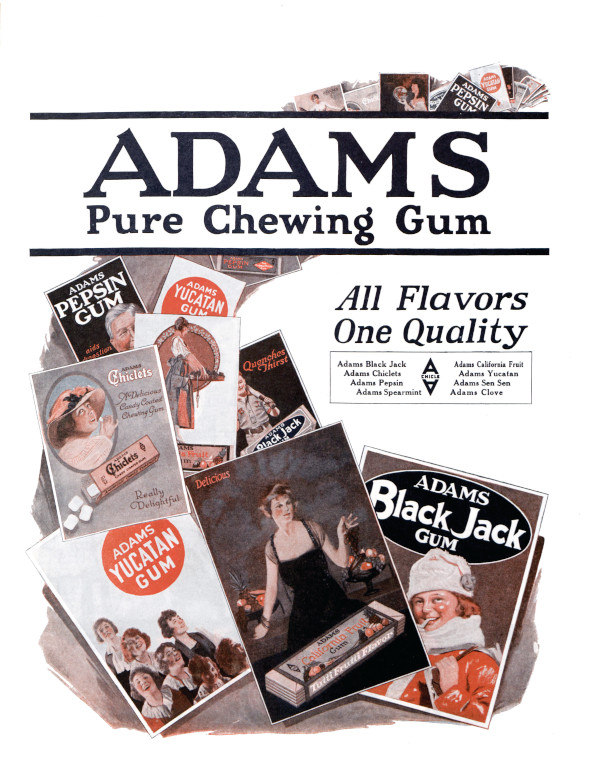

How a Mexican Dictator Helped Invent Chewing Gum

America’s chewing gum industry began with the help of a deposed Mexican dictator. In the 1850s, Thomas Adams was secretary to General López de Santa Anna, then living in New York and plotting a return to power in Mexico. Santa Anna had arrived in New York with a boatload of chicle, a latex substance from the sapodilla tree, and the idea of selling it as an inexpensive alternative to rubber. It never caught on with buggy-tire makers, but Adams realized chicle could be made into chewing gum. After purchasing the cargo from Santa Anna, Adams began adding flavorings to the chicle. By 1871, he was selling “Adams New York Chewing Gum” in drugstores. In 1884, he introduced his first big hit: licorice-flavored “Black Jack” gum. In 1899, he introduced the popular Chiclets, as well as the vending machine, from which he dispensed his gum on New York City subway platforms. The Adams company continued production for decades, adding new flavors like Clove and Pepsin. But in the 1970s, declining sales caused the company to cease production. Now owned by the British confectionary company Cadbury, the company is again manufacturing gum and, for older gum chewers, nostalgia.

This article is featured in the July/August 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.