What Happens When You Talk About Politics in Person

The day before the Iowa caucuses, I boarded a bus at 5 a.m. to travel five-and-a-half hours to Dubuque, Iowa. A group of about 50 of us descended on the old river city to canvass potential voters. That is, we walked door to door and tried to convince whoever was inside to caucus for our candidate. I won’t say which candidate we were speaking for, but — as a hint — it wasn’t Deval Patrick or Michael Bennet.

I’ve canvassed before — for candidates and specific issues — but Iowa was a little different. To be sure, on the day before their highly publicized caucus in an election year that is looking more and more to be incredibly dramatic and hotly contested, most Iowans were sick of talking politics. Since the state is placed on a disproportionately high pedestal in the primaries, Iowans are routinely bombarded by throngs of presidential hopefuls every four years.

We arrived at the campaign office in Dubuque, and the local staff gave us a brief training in political canvassing. Of course, the goal is to persuade voters that your candidate is best for the job, but that isn’t always as straightforward as it sounds.

Like a significant portion of the country, I like to discuss politics online. Political discourse, between news comment threads, Facebook memes, and nonstop tweeting, ranges from enlightening (really!) to noxious to utterly untrue. The internet has transformed the way we talk about politics and government.

And, still, there is something to be said for a face-to-face conversation.

In spite of the potentially tremendous reach of a well-run online campaign, it doesn’t always have the same effect as the physical presence of a group of canvassers — especially if that group numbers in the thousands. Humans, in the flesh, talking to other humans can eliminate many perceptions of disingenuousness that percolate from the web. Of all the things I’ve been accused of while canvassing, being a robot has never been one of them.

After we received information on where we’d be canvassing, I set out with a group to the location. A local guy drove us to a suburban-looking neighborhood on the outskirts. He had grown up in Dubuque and was proud of his city, so it seemed as though he took the long route to show us its glowing golden-domed courthouse and the historic hillside cable-car elevator.

When he dropped us off, we marched up to the first house on our list. We had a name — let’s say Jason — and an age, 41. I knocked on the door, and we waited. This is the worst part of canvassing: awkwardly waiting on a stranger’s doorstep, feeling entirely out of place. When Jason opened the door, he confirmed our fears. He cut off our opening line, saying “You people have been here three times this weekend. If this keeps up, I’m going to vote for Trump.”

He closed the door on us, but it didn’t seem as though we were going to be successful in getting him to fill out a caucus confirmation card anyway, so we moved on to the next house. Door after door, we were met with disinterest, irritation, or no one at all. We began to think the endeavor was a bust. Even if we were passively distributing literature on Iowans’ front doors, it seemed as though we wouldn’t get the opportunity to turn out any voters.

Then we met David, a young dad who was just intoxicated enough to indulge us with friendliness and attention (it was the day of the Big Game, after all). He didn’t follow politics much, and he wasn’t aware of the caucus happening the next day, but he was interested in how policies could directly influence his family’s lives. We told David that we travelled hours that morning to talk to people like him because we believed in our candidate.

Even when people aren’t interested in following a political horse race, they can recognize genuine passion in a face-to-face conversation. A person who doesn’t devour the news might not have much of an impression of a presidential candidate’s tailored persona, but they can probably gauge the enthusiasm of a volunteer looking them in the eyes and describing their personal stakes in an election.

David was receptive, but we weren’t convinced that he would turn out to caucus the next day. It was a lot to ask: showing up in the evening to some church or college lecture hall and standing around for a few hours while people shuffle around the room to declare their support for one candidate or another. Many people we spoke to said they had work or other commitments that would prevent them from attending.

Toward the end of our route, at the second-to-last door we knocked, Amy answered the door. We were looking for a different voter at that address, but she said it was her sister-in-law, who hadn’t lived there in years. When we knocked, her dogs barked and woke her child from a nap. We apologized, but she was happy to see us and interested in talking about our candidate.

“I don’t know all of the issues up and down,” she said, “but I’m a definite supporter.”

Amy was a veteran, and she was hopeful about the kinds of changes our candidate could bring about. I asked her if she planned to caucus the next day. She was surprised that it was happening so soon, and she said she wouldn’t be able to make it because of her kids.

“You can take children to the caucus,” I said.

But she said it was during dinnertime and would be a hassle.

During canvassing training, volunteers are instructed to make the conversation as personal as possible. Before leaving, though, it is important to make a definite ask for support in the caucus. Even though it can be hard, it is important to let people know that they are being counted on. I looked at Amy and the bright blond boy hanging at her waist. She had been eager to talk about the issues and the political direction of the country at length, but making her voice count was just out of reach. I handed her a flyer with her caucus information on it and weakly asked her to reconsider.

We talked to others, some Republicans and some with plans to caucus for other Democrats. Occasionally they seemed reticent, like we might hurl arguments or insults once we found out they didn’t support our candidate. There wasn’t the time or appetite for that, though. We had doors to knock and they had snow to plow. We wished them well, and they did the same.

On the long bus ride home, I couldn’t help but think of Amy as my great failure of the day. Maybe she would caucus after all, but probably not. Should I have pushed her a little harder? Could it possibly have made a difference? Maybe the best scenario we could hope for was that she realized some other people felt strongly in the same ways she did, and, even though it can be nerve-wracking, it’s not so impossible to talk about it.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Take an Epic Road Trip on the Lewis and Clark Trail

More than 200 years ago, President Thomas Jefferson commissioned the Corps of Discovery, led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, to explore the Louisiana Purchase and beyond. Journeying on the longest river in the present-day United States, Lewis and Clark’s team made their way across the continent to map the terrain, document wildlife, and establish relationships with native tribes. After a year and a half — and more than 4,000 miles — the Corps reached the Pacific Ocean.

Though the rivers and terrain traversed by the Corps of Discovery have changed over the years — for both natural and manmade reasons — you can still take a path comparable to theirs across the country. This year, the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail was extended to Pittsburgh to recognize the extensive preparations for the expedition that technically began near St. Louis. Traveling the 4,900 miles of the trail by car should take around a month, depending on how many of the hundreds of historical and natural stopovers you plan to include in your trip. The opportunity to encounter the complicated past of the country and its peoples firsthand is one that you’ll never forget.

St. Charles, Missouri

The Corps of Discovery reportedly bought all of the tobacco in St. Charles before venturing into the wilderness of the Louisiana Territory up the Missouri River. The Lewis and Clark Boathouse and Nature Center houses replicas of the keelboats that carried the team on their journey as well as interactive exhibits and a nature park. Nearby Frontier Park marks the spot where the Corps camped for five days, and — beginning there — you can bike 165 miles of Lewis and Clark’s route along the Missouri on the Katy Trail. If that seems like a lengthy trip, you can hike a mile or two of the trail instead.

Independence, Missouri

The hometown of President Harry S. Truman was also the place where Clark was separated from the party while hunting and found his way back by firing his rifle into the air. Independence is home to the National Frontier Trails Museum, where you can see artifacts and exhibits concerning the Oregon, California, and Santa Fe Trails as well as the Lewis and Clark Trail and the Mormon Pioneer Trail. About 14 miles outside of the city is Fort Osage, an outpost built under the direction of Clark after the expedition to defend the Louisiana Territory and trade with the Osage tribe.

The Loess Hills, Iowa

This region on the western edge of Iowa is known for its rolling hills and bluffs created by winds at the end of the last ice age. Visit the Waubonsie State Park, near Sidney, for trails and views of the Missouri River, and stop by the Mills County Historical Museum, in Glenwood, to see prehistoric Native American artifacts and a reproduction of a first-century earth lodge.

Pierre and Mobridge, South Dakota

The Corps of Discovery first encountered the Teton Sioux in Pierre. The Bad River Encounter Site marks the location of the council between the party and the tribe that almost turned deadly, and the downtown South Dakota Cultural Heritage Center offers interactive exhibits about early Native Americans and the settlers that followed. Further along the trail is Mobridge, a city across the river from the Standing Rock Reservation. The site of the now-destroyed Fort Manuel is where Sacagawea died six years after her journey with the Corps. Monuments to Sacagawea and Sitting Bull were erected on the reservation just across the river from Mobridge.

The Missouri Breaks, Montana

The Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument covers 149 miles of the river that took the Corps of Discovery three weeks to traverse. The badlands, cliffs, and plains of the area are largely unchanged since Lewis and Clark’s expedition and a must-see of any Lewis and Clark road trip. Be sure to visit the site where the Corps camped at Slaughter River — so named for their discovery of more than 100 dead buffalo — and the White Cliffs of the Missouri, where the Corps would have been shocked to see such geological splendor after spending time in “a country which presents little to our view, but scenes of bareness and desolation.”

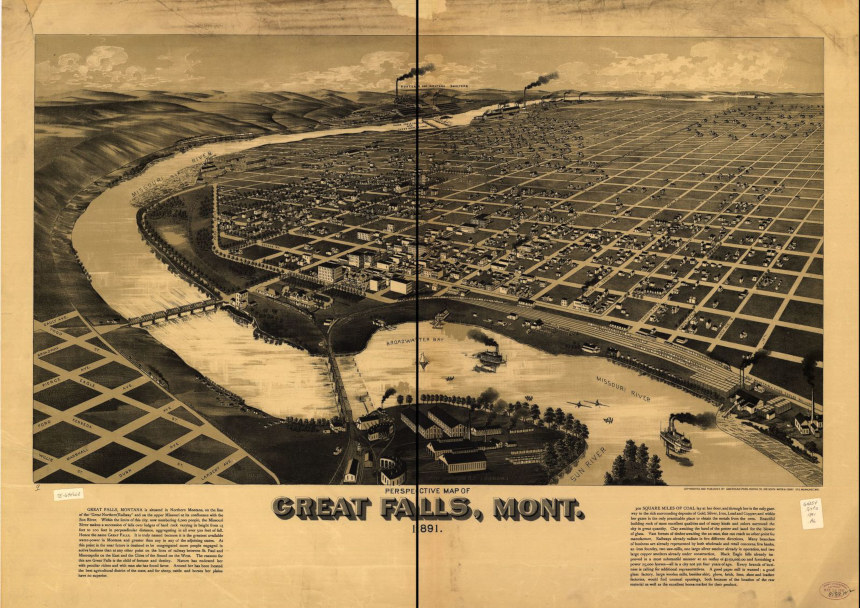

Great Falls, Montana

Lewis described the first of the five Great Falls as “a truly magnificent and sublimely grand object” when the Corps came upon the 400-foot waterfall in June of 1805. The group also took note of the freshwater springs now housed in Giant Springs State Park, which now feeds into a fish hatchery. Take advantage of the wildlife and breathtaking sights around this Montana hub, and visit during the Lewis and Clark Festival in June to enrich your historical adventure.

Salmon, Idaho

The Sacagawea Interpretive, Cultural, and Education Center sits just outside the town of Salmon, where Sacagawea was born. The museum offers an outdoors experience of the Shoshone tribe to supplement the Lemhi County Historical Museum’s wealth of Lemhi Shoshone artifacts and exhibits. If you take a half-day to drive the Lewis and Clark Back Country Byway and Adventure Road, the single-lane gravel road leads past several camps and sites along their trail. One of the most significant of these is Lemhi Pass, where the Corps stood and noticed “immense ranges of mountains still to the west” after thinking they were getting out of the Rockies.

The Dalles, Oregon

Clark estimated a village in the Columbia River Gorge to be drying 10,000 pounds of salmon when they passed through in 1805. The Corps traveled into the densely forested canyon from the arid desert of eastern Oregon, and — with breathtaking waterfalls, cliffs, and vistas — the area continues to be a land of plenty. The Dalles is the perfect place to learn and play, with the renowned Columbia Gorge Discovery Center giving an exhaustive history of the Gorge and places like Celilo Park offering spots for windsurfing and swimming.

Ilwaco, Washington

When the team reached the eastern end of Gray’s Bay, close to where the Columbia meets the Pacific, Clark wrote “Ocian in view! O! the joy” in his journal. As it turned out, they were still about 20 miles, and three weeks of storms, from sea. They reached the Pacific, eventually, in present-day Ilwaco, Washington. Cape Disappointment’s Lewis and Clark Interpretative Center offers a history lesson on the Corps’ journey against the backdrop of an 1856 lighthouse and the pounding surf of the Pacific.

Astoria, Oregon

Although the Corps of Discovery first met with the ocean in present-day Washington, the party took a vote that decided they would stay for the winter across the Columbia river in what is now Astoria, Oregon. They built Fort Clatsop and stayed from December 1805 to March 1806 — during which there were only six days without rain. The Lewis and Clark National Historical Park gives guided canoe tours, reenactments, and a replica of the original fort where the Corps spent their miserable winter thousands of miles from home.

Featured image: Ericshawwhite, Wikimedia Commons, via the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license