The Splendor of Ruins

The built landscape is often how we relate visually to history. We visit archaeological sites, monuments, churches, temples, mosques, museums, forts, castles, and buildings of state. We speak of the pleasure and splendor of ruins — but how often does an architect contemplate what their creation will look like when it falls into decay? Will it still have a tangible presence? It is time going backward, returning to the beginning and exposing the bones of the structure. Archaeological sites have a form and presence never anticipated by the builders; in their altered state, we are embraced in a backward-gazing dream.

For many sites, the façade is everything. Builders were aware of light and shadow and how the interplay of the two would change throughout the day. The setting can be just as important and seductive. This would be important regardless of whether the building was religious, monumental, utilitarian, or residential.

While ruins remind us how much we have forgotten, they also give us license to dream.

Architecture is often used to make religious and cultural statements. For example, Bayon, at Angkor Thom, in Cambodia, is a state temple, a complex monument that uses face towers to create stone mountains of ascending peaks, and below are two bas-relief galleries with delicately carved historical, religious, and mythological subjects sweeping across the walls. Dancing Apsarases — spirits of the clouds and waters — are incised on pillars.

In Europe, the façades of cathedrals have saints, clerics, and angels floating above our heads, and the interior is a manmade space meant to encompass the heavens and earth, with soaring ceilings and rich imagery and decoration. They invite the congregation to worship and pray. Everyone has access to God. The altarpiece is an artistic testament to God’s power and glory and the focus of the richest display of wealth: paintings, gold leaf, carvings, and elaborate niches. Windows let in light, sometimes through stained glass, which adds a kaleidoscope of rainbow colors dancing on the floor and walls as the sun moves. It is light, mysterious, and holy.

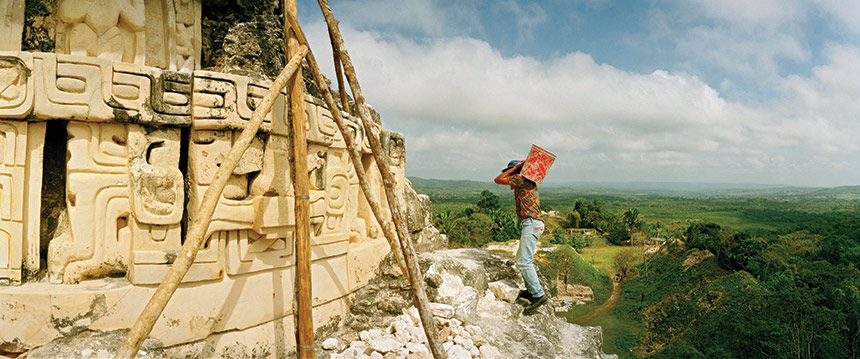

In the Americas, the Maya wrote their history on the outside of their buildings. Like any culture that believes the earth is alive, they used objects as symbols for the natural world. Their pyramids were mountains, and the doorways of their temples were the mouths of those mountains — cave entrances. Their Classic Period was noted for elite architecture, propagandistic monuments, and flamboyant theater-state rituals where epicenters of Maya sites were constructed as stage settings for religious spectacles, demonstrating the political and spiritual power of the rulers.

Humanity’s early impact on the landscape is found in the megalithic sites of Europe. Standing stones, stone circles, and cairns date to the Neolithic period and the Bronze Age. People have probably been anthropomorphizing the stones since soon after they were erected — brooding, pensive figures — maybe even witches or faeries in the woods or open moor. The builders of the Neolithic burial chamber at Pentre Ifan in Wales would never have intended it to be viewed as it is today — a large and elegant capstone balanced delicately on the tips of upright stones. They covered it with a mound of earth 130 feet long, traces of which still remain, but thousands of years of wind and rain have exposed the very essence of its design, revealing a monument of lyrical grace, equal to or surpassing modern sculpture.

An archaeological zone is referred to as a “dig” because we literally have to shovel through centuries of detritus to uncover the buildings to discover the site. There might only be the most teasing of hints, but often nothing left on the surface to tell us what will lie beneath. In the tropics we have archaeology under the canopy, mature hardwood forests crowning what once were palaces and pyramids, their roots, over time, inexorably crumbling masonry walls and breaking lintels in two.

We can see fragments of this happening today even where we live. The weeds that spring from the smallest of crevices; a sidewalk broken by a tree root, its outline traced by the bulges and cracks of the concrete; a vacant yard turned feral by neglect or foreclosure. Leaves and weeds accumulate, break down, and the mulch becomes soil. More weeds, bushes, and trees take root in the soil that collects on rooftops, inside vacant buildings, along abandoned tracks. An animal builds its nest, a bird drops a seed, and each and every thing adds its part — a reminder that, even in a city, we live in nature, even if that nature is a product of human influence. People and their towns and cities might hold nature in abeyance, by differing degrees, but it is always a part of our world, and once a city goes into decline or is abandoned, the natural world takes over.

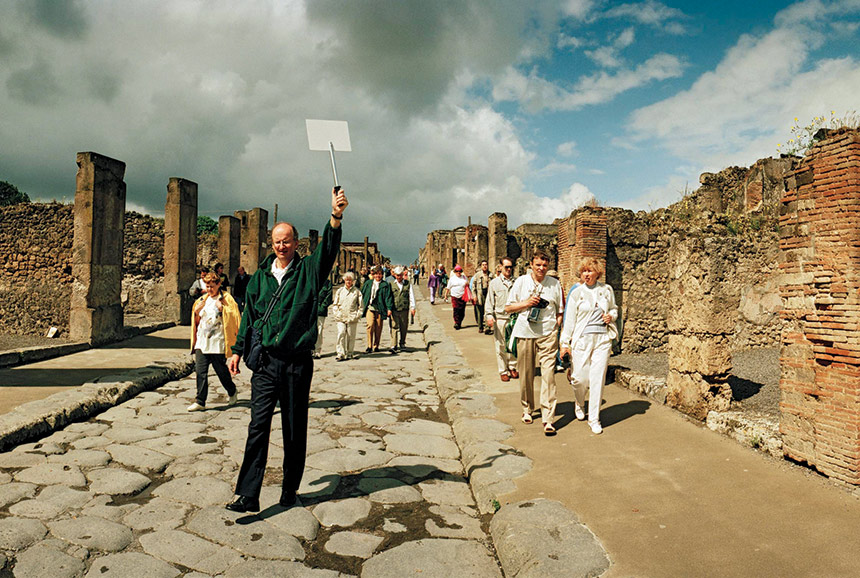

Ruins provide us an enigma to study and try to decipher. We walk around trying to see the overall picture, meanwhile looking for the details that will inform our thoughts, and we are free to come up with our own hypotheses. Many archaeological sites are in park-like environments — they can be pleasant to visit. People bring picnics and play games and turn it into a family outing, cheerfully oblivious or simply enjoying that, once upon a time, intrigue and pageantry inhabited the spot. They might nibble on their appetizers where soldiers once massed, kings spoke to their subjects, merchants contemplated perilous and long journeys, and captives were sacrificed.

While ruins remind us how much we have forgotten, they also give us license to dream. We can try to imagine what buildings once looked like, what a square full of people might have sounded like, what the market might have smelled like packed with vendors and all the wealth of their wares. Ruins expose us to cultures we might not have known existed, to history we can look forward to learning, to discovering more about the people who probably never entertained the thought that one day we would be standing here wondering who they were.

We think of ruins as being isolated cultural sites, but our effect on the earth has been so significant that we have entered the Anthropocene Era. Sometimes we deceive ourselves into thinking that these changes have been utterly natural, but we are living in the ruins of a natural disaster of our own making, a process started thousands of years ago but accelerating quickly. “Nature is not a temple, but a ruin,” writes J.B. MacKinnon in The Once and Future World: Nature as It Was, as It Is, as It Could Be. “A beautiful ruin, but a ruin all the same.”

Just as Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote about impermanence in his sonnet “Ozymandias,” and later Robinson Jeffers in his poem “Hands,” we should realize that one day someone will stand where we now live and wonder who we were.

Photographer Macduff Everton wrote The Modern Maya (UT Press) and collaborated with Linda Schele and Peter Mathews on The Code of Kings: The Language of Seven Sacred Maya Temples and Tombs (Scribner). For more, visit macduffeverton.com.

This article is featured in the March/April 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Sans Souci, Haiti: Built between 1810 and 1813, the ruins of the royal palace of King Christophe (Henry I) are now a National History Park and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Copyright © Macduff Everton. All rights reserved.

After 100 Years, Fellini’s Dreams Still Resonate

Every summer, a handful of tourists in Rome — sometimes naked and usually drunk — take a dip in the shallow waters of the Trevi Fountain. Because the Baroque landmark is guarded constantly by Roman police officers, the misguided swimmers are often caught and fined (400 euros and up).

Whether or not they are aware of it, their illicit bathing is an homage to Anita Ekberg’s iconic swim in Fellini’s 1960 film La Dolce Vita. Her character Sylvia, a bodacious actress, wades into the fountain at night, swaying underneath the waterfall issuing from the giant Oceanus statue in the center. She beckons Marcello, a tabloid journalist, to join her before baptizing him in the water. Soon, he awakens behind the wheel of his Triumph TR3.

Such dreamlike scenes are customary in the films of Italian director Federico Fellini. Throughout his career, spanning postwar Italy to the 1980s, Fellini became one of the most famous movie makers in the world with his expressionist romps that explored fame, fidelity, and the human subconscious. Today is the 100th anniversary of his birth.

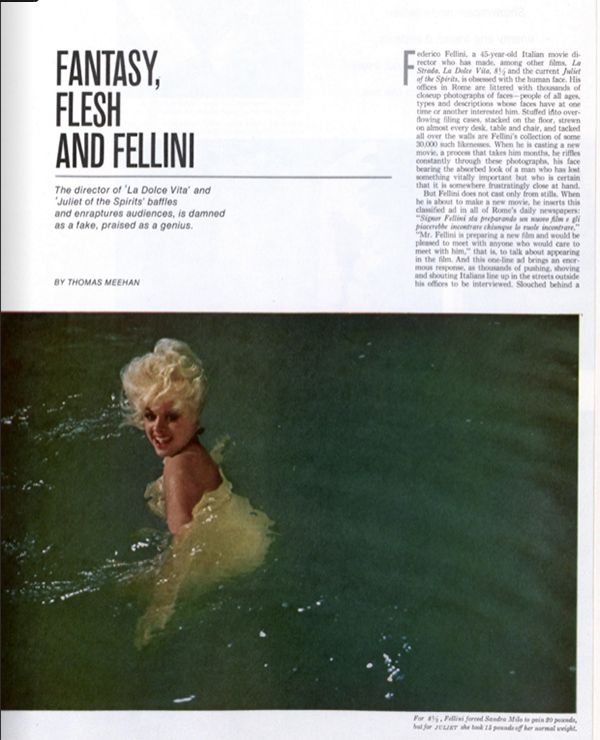

In the 1960s, Fellini was gaining momentum with one blockbuster success after another. Although his films were making a fortune, the director wasn’t seeing much of the money due to some poor financial decisions. In 1966, the Post published a profile of the Italian auteur called “Fantasy, Flesh, and Fellini.” The story paints Fellini as a larger-than-life artist, claiming he worked ungodly hours and followed a rigorous casting regimen, meeting thousands of everyday Italians before choosing the faces to put in his movies.

Fellini had a reputation, corroborated by the Post’s profile, for being extremely eccentric, bordering on narcissistic, and all for the sake of uncompromising artistic vision. Just as his fans may have imagined, writer Thomas Meehan claimed he pored over characters and scenarios for months before improvising entire film shoots, and he manipulated actors with his charm and punishment to elicit perfect performances.

His films were largely autobiographical, with his wife Giulietta Masina often playing a lead role (and sometimes portraying herself). Their rocky marriage, and his womanizing inclinations, were on display in his back-to-back films 8 ½ and Juliet of the Spirits. Amid the fantastical and supernatural happenings in both movies are two separate stories of the inner strife and sexuality of Fellini and Masina, told, respectively, from each point of view.

“I set about creating films perhaps in the way that Marco Polo sailed for the Orient,” Fellini told Meehan, “not knowing really what may happen along the journey or where the end may lie — on a voyage of discovery.” It isn’t beyond belief that Fellini would direct this way, to watch his films. Scenes from films like Roma, La Dolce Vita, and City of Women often feel as guided by large-scale contrivances as they are by natural improvisation.

Although Fellini won four Oscars for Best Foreign Language Film, he never took home the award for Best Director.

His meditations on honesty, infidelity, sensuality, and — especially — the vacuousness of fame were novel in the 1960s and ’70s, but they remain as relevant as ever. Regardless of whether or not Fellini would actually act out each scene in full for his performers before shooting or work himself into a violent rage over an unsatisfying performance, his movies speak for themselves.

At the Trevi Fountain, Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, with its portrayal of people in a vapid race for fame and fortune, resounds during the daytime as sunhatted tourists battle for the perfect selfie spot. After midnight, when the crowd has thinned and the sound of Oceanus’s waterfall echoes around the cobblestone streets, Fellini’s dreams seem a little closer to reality.

My Top Ten Fellini Films:

- Juliet of the Spirits

- La Strada

- Amarcord

- Satyricon

- La Dolce Vita

- I Vitelloni

- 8 ½

- Nights of Cabiria

- Roma

- City of Women

Featured image: Marcello Mastroianni in 8 1/2 (Wikimedia Commons / public domain)

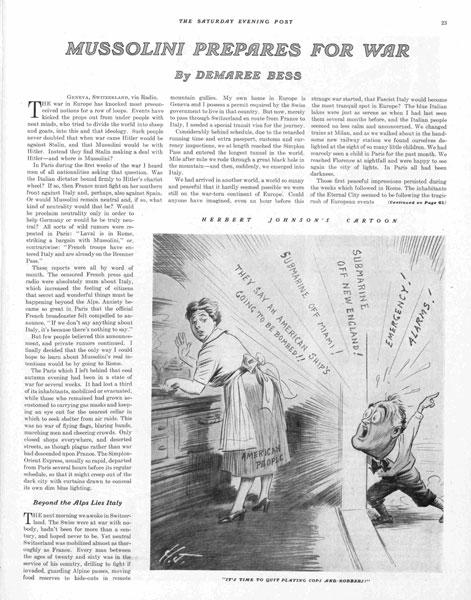

On the Sidelines, Mussolini Awaits His Opportunity

( via Wikimedia Commons)

You may have seen the photos of Benito Mussolini’s messy demise. The photos show the corpse of Italy’s ex-dictator, shot, beaten, and kicked, hanging upside down from the roof of a gas station. Seeing the brutality of his death, you get a sense of how fiercely the Italians hated the man who had dragged their country into a war that brought only poverty, disgrace, and death to their land.

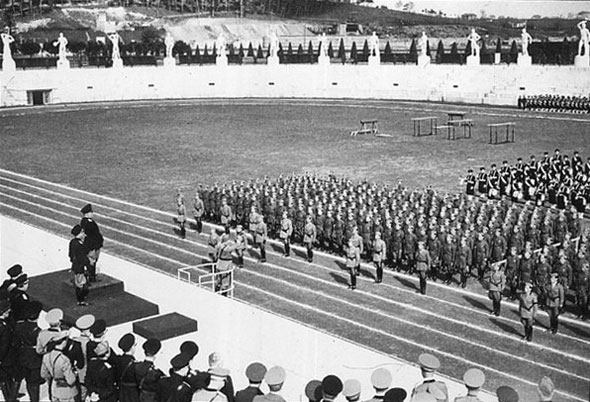

Once Mussolini had enjoyed broad support in Italy. He presented himself as the savior of the country, promoting fascism as the solution for the country’s problems. He inspired young Italians to join forces, donning the black shirts of the fascist party members. He also inspired a young Austrian named Adolf Hitler, who looked up to Mussolini as a role model.

But Hitler was a fanatic. Mussolini was an opportunist. And nothing illustrated his opportunism better than his actions in 1939. In May of that year, he and Hitler signed an alliance in which they pledged to come to each other’s aid in the event of war.

Furthermore, the agreement “stipulated that neither of the parties would take action within the next three years [to] cause war in the West,” wrote Post correspondent Demaree Bess. [Read the entire article “Mussolini Prepares for War” from the Nov. 18, 1939 issue of the Post here.] Mussolini needed that delay. His advisors had told him Italy wouldn’t be ready to launch a war before 1942.

Not surprisingly, Hitler ignored this clause in the agreement when, just four months later, he declared war on Poland. As his army launched its blitzkrieg, the world looked to his ally Mussolini. What would Il Duce (the Italians title for “the leader) do now?

Bess was hearing all sorts of wild rumors of possible alliances and confrontations—an alliance between France and Italy, war between France and Italy, even an attack from Germany. “I finally decided that the only way I could hope to learn about Mussolini’s real intentions would be by going to Rome,” he wrote.

Bess left a darkened, huddled Paris that anticipated German bombers at any moment. Traveling south, he found Italy sunny and peaceful. “As we walked about in the handsome new [Milan] railway station, we found ourselves delighted at the sight of so many little children. We had scarcely seen a child in Paris for the past month. We reached Florence at nightfall and were happy to see again the city of lights.”

The Italians were happy again with il Duce, then regarded as a man of peace. He was making no overt moves to drag Italy into Hitler’s crusade against France and England. “[Italy] seemed to be in a position to stay neutral as long as she liked — and to make money trading with the belligerents,” Bess wrote. Yet he became convinced that Mussolini had no intention of staying out of the war a moment longer than necessary. “He is standing on the side line now, watching how things go, but he isn’t idle. … He is preparing for war.”

Il Duce had set the country on the road to war many years earlier. “He has raised a whole generation of Italian youth in the faith that they should live dangerously, that pacifism is a vice,” Bess wrote. And now, though Italy was still neutral, Mussolini’s government was starting to ration food for civilians and stockpile it for the army.

Mussolini’s refusal to join Germany’s war prompted some to believe he was reconsidering his alliance with Hitler, which had always been “extremely unpopular with Italians,” Bess wrote. “Italians naturally dislike Germans. The two races don’t get along well together. Germans are impatient with the easygoing temperament of Italians and don’t conceal their impatience. Italians resent German assumptions of superiority merely because they are more efficient.”

For now, the Germans weren’t pressuring Italy to join their fight. In fact, Hitler found Italian neutrality useful. According to Bess, it allowed Mussolini to play a peacemaker who suggested there could be a “settlement of the war in the West, thus enabling Hitler to pose before his own people as a reasonable man who didn’t want to fight Britain and France.”

France and Great Britain were also satisfied with Italian neutrality, since it enabled them to maintain their control of the Mediterranean Sea without having to engage the Italian fleet.

Mussolini was under no pressure to commit Italy to the world war. “He foresaw that no pressure from either side could or would compel him to enter this war until he was ready to move,” Bess wrote. “Germany’s air force might destroy Italian cities, but what could Germany gain from that?”

Mussolini would remain neutral for as long as it was profitable. But Hitler’s swift victory over France led Mussolini to weigh the profits from war versus peace. If he remained out of the fight, his country might continue its gradual rise in prosperity. And he might take up the offer of trading concession in Africa that Great Britain and France would grant if Italy remained neutral.

But if Italy entered the fight, it might be able to share in Germany’s looting of conquered France. All he needed, Mussolini told his military chief, was to lose a few thousand Italian soldiers in the war to earn a share of the spoils at the victor’s table. And then Italy could simply seize whatever African colonies had belonged to the Allies.

Above all, Mussolini became trapped by his own bravado. Having posed as a modern-day Caesar, he needed to prove the might of his country’s forces.

On June 10, 1940, he committed Italy to the war. He sent his soldiers into France, prompting President Roosevelt to comment, “The hand that held the dagger has struck it into the back of its neighbor.”

The decision began a long, sharp decline in the fortunes of both Italy, and Mussolini, who suffered the consequences in Milan at the hands of an enraged mob.

Step into 1939 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 75 years ago: