Manson, Dylan, Einstein, Lincoln: Visit the Largest Private Document Archive in the World

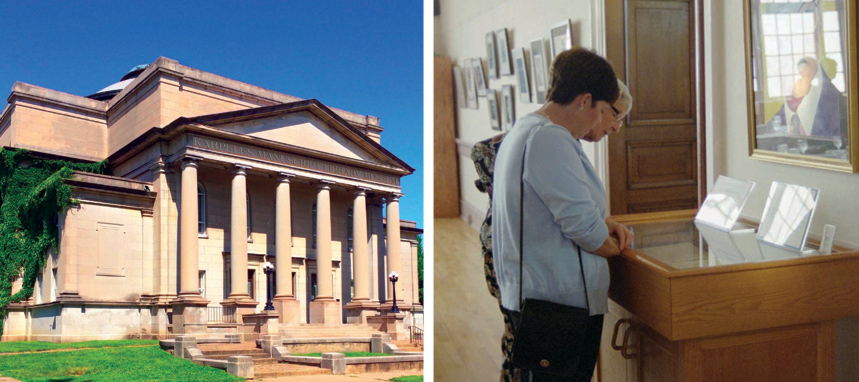

At one point, we even had a Charles Manson letter here,” recalls Richard Minor, a mischievous smile creeping into his voice. Minor has served as director of the Karpeles Manuscript Library in Jacksonville, Florida, for 11 years.

“People come in thinking they’re just going to see reproductions, and then they realize that they’re looking at originals. Sometimes even with the original ink stains on the paper.”

“There was a yellow stain on one corner marked pee, with an arrow pointing to it,” he laughs. “That was one document I really didn’t want to touch.”

The missive was part of an exhibit called “Letters from the Pen,” a collection of letters from some of the world’s most notable, and hopefully more hygienic, people serving time. Mary Queen of Scots had a letter in this exhibit. So did Galileo, Sir Walter Raleigh, and Napoleon. Pope Pius VII was represented, along with abolitionist John Brown. There was even a letter from Leon Czolgosz — who? — the man who assassinated President William McKinley.

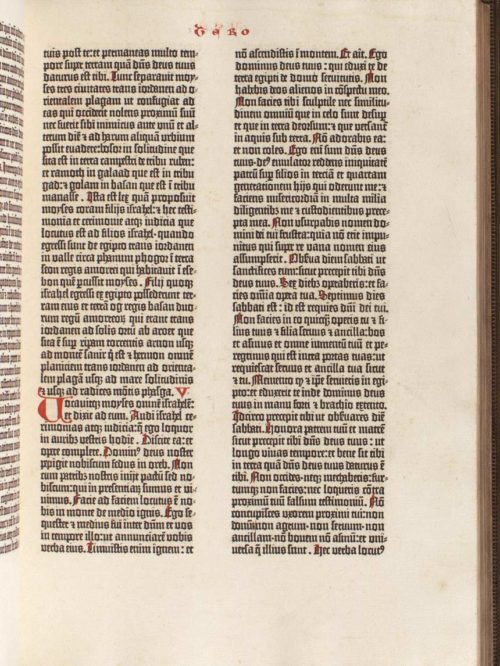

But then collecting and preserving historical documents is what the Karpeles Manuscript Libraries are all about. With more than a million originals to its name, the collection is the largest private archive of its kind in the world — an archive as eclectic as it is massive.

The libraries are the brainchild of David and Marsha Karpeles (“KAR-pluhz”). The story began nearly 40 years ago when the real estate mogul and his wife dragged their reluctant kids to California’s Huntington Library. David Karpeles still smiles when thinking of that day in the late 1970s, when his bored kids suddenly became mesmerized by the historical documents on display. “All of a sudden I heard my daughter say, ‘Look Daddy, it’s Thomas Jefferson. And his handwriting looks just like mine.’

“So, I went over to the display case and said, ‘You’re right. It does look just like a fifth grader’s.’

“Then my son, not to be outdone, said ‘Dad, come over here! George Washington crossed out things, too. He made mistakes just like I do.’

“I think the difference was that in school, they just saw pictures in books. But these were actual documents that these great men had touched,” Karpeles says, acknowledging that his kids’ reactions set off a lightbulb of inspiration. It was on that day that David and Marsha Karpeles decided to focus their philanthropic energy on building a series of manuscript libraries.

Almost immediately, they began collecting their own historical documents, with Sotheby’s and Christie’s auction houses among their prime hunting grounds.

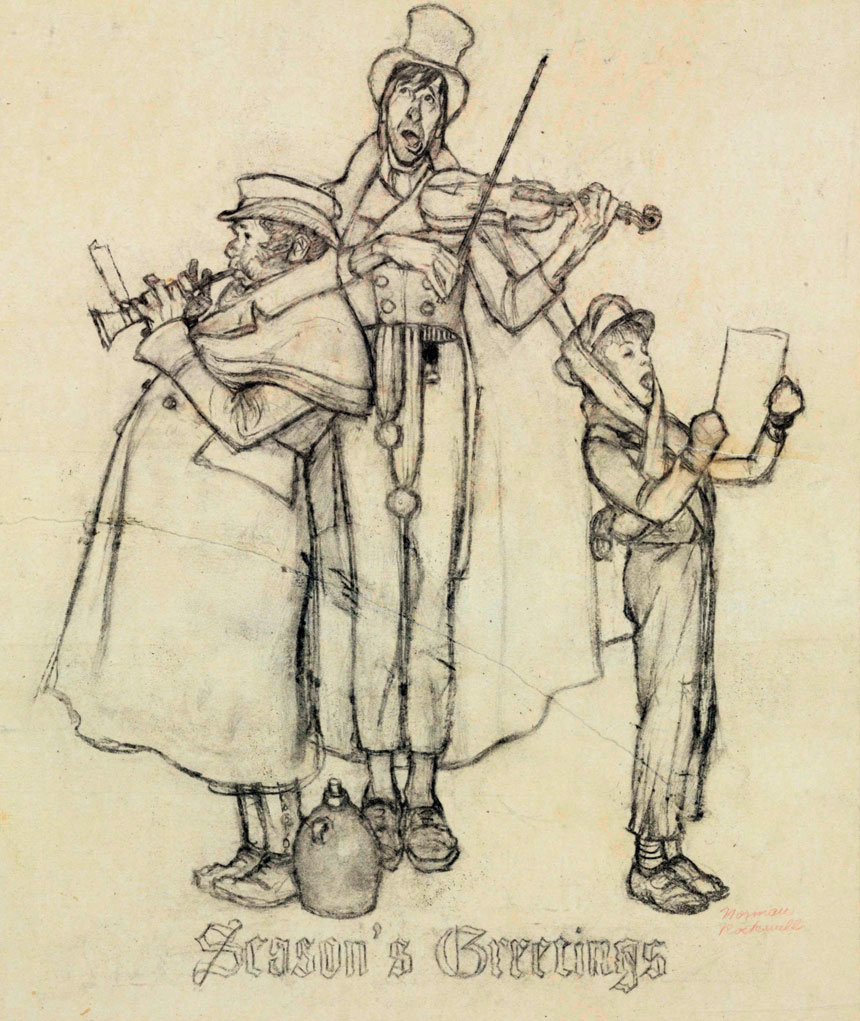

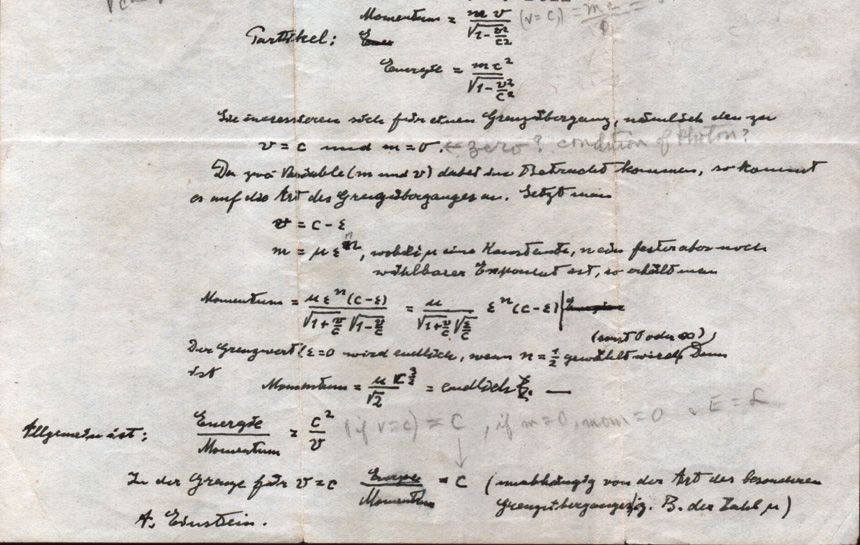

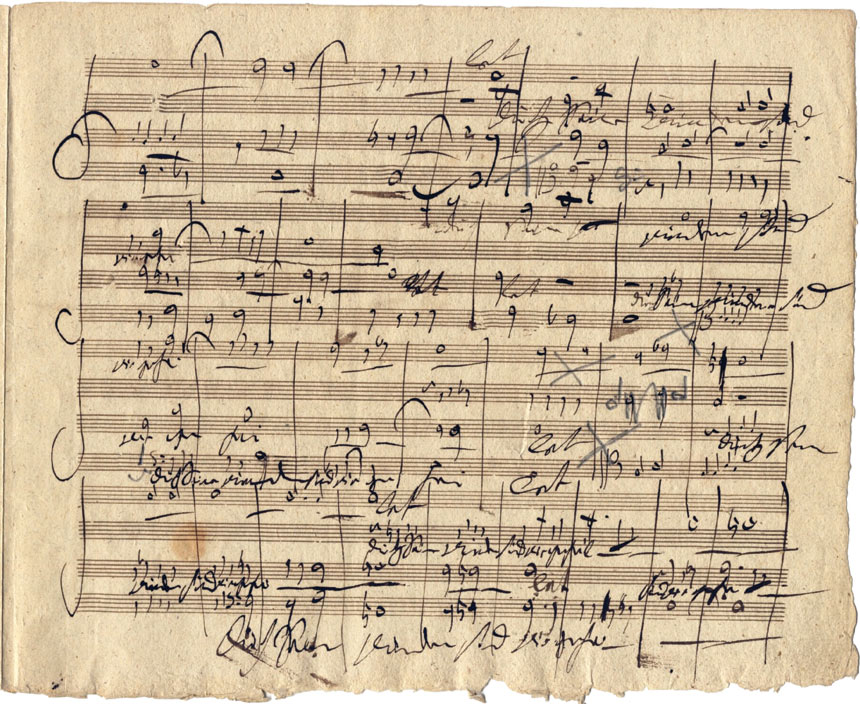

Today there are 14 Karpeles Manuscript Libraries dotting the country. Included in their displays are practically anything you can think of. The original manuscript of Wagner’s “Wedding March”? Have it. A manuscript of Einstein explaining his theory of relativity? Have it. The Constitution of the Confederate States of America? The official rescue report from the Titanic? Lindbergh’s actual landing certificate following his fabled transatlantic flight? Have it. Have it. Have it.

Early on, Karpeles chose not to open in big cities like LA, Chicago, or Boston. He was convinced to select less culturally satiated cities for his libraries when only 69 people showed up to see an original draft of the Bill of Rights at the launch of a New York City location. He promptly closed it and instead opened his libraries in places like Santa Barbara, Jacksonville, Shreveport, and Fort Wayne. Validation for Karpeles’ small-city approach would not be long in coming. When the very same Bill of Rights showed up in Tacoma, “Not only was the library full to bursting, but cars were jammed up six blocks in every direction,” Karpeles says. “I couldn’t believe it.”

It’s a thrilling experience to see these documents firsthand, says John Snow, director of the Karpeles Manuscript Library in Rock Island, Illinois. “People come in thinking they’re just going to see reproductions, and then they realize that they’re looking at originals,” Snow says. “Sometimes even with the original ink stains on the paper. They’re so excited to be so close to a real piece of history, and to see it with their very own eyes.”

It’s an excitement David Karpeles has long believed in sharing. Every year he personally assembles several new exhibits from his archives, which then rotate through his 14 libraries on a four-month schedule. Local directors also have the flexibility to mount exhibits from outside sources if Karpeles gives the okay. One that quickly got his blessing was an exhibit on Bob Dylan recently displayed at the Karpeles Manuscript Library in Duluth. It was an easy pitch, according to Library Director Doris Malkmus. And not just because Duluth was Dylan’s hometown. “David actually knew Bob Dylan when they were kids growing up in Duluth,” explained Malkmus.

Documents don’t always go directly to Karpeles Libraries. Sometimes they take road trips. The Karpeles “mini-museum” program, as it’s called, offers themed materials to local schools, even providing display cases if needed, to give kids a look at history up close and personal.

Nobody gets up close more than the Karpeles Library directors themselves. And, like their library visitors, they often have favorite exhibits.

Director John Snow was excited by two Civil War displays. One about its early years, the other on its conclusion, including an original manuscript detailing the momentous events of Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox.

“It all had a very personal touch,” Snow says. “There were letters from President Lincoln, even some regarding troop movements. They gave you a real glimpse of what was going on behind the scenes.”

Duluth’s Director Doris Malkmus was especially moved by examining the Plains Indians Treaties, a series of agreements ostensibly designed to promote peace but, in reality,

designed to force Native Americans westward to make room for the wave of settlers arriving from the East. “We have treaties with the original thumbprints and x’s of the major native tribes,” Malkmus says, noting the many treaty violations later made by the U.S. government. “You can almost imagine what it was like to be a Native American at the time through seeing the treaties themselves.”

Jacksonville’s Director Richard Minor liked both a Sherlock Holmes exhibit, with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s original pages for The Hound of the Baskervilles, and an exhibit featuring several handwritten pages by Founding Father Samuel Adams. (And, yes, the family did actually own a brewery.) “Adams had written maybe two pages,” Minor says, “and, I guess, he’d gotten up and left the room. Because while he was out, one of his grandchildren had come in and scribbled all over the page.

“That one still kills me,” he laughs, “because it showed Adams was a real person with the same sort of inconveniences that we all have to deal with.”

And what about David Karpeles, now in his 80s but still engaged in his life’s mission? With so many possible choices, could he possibly come up with a standout favorite?

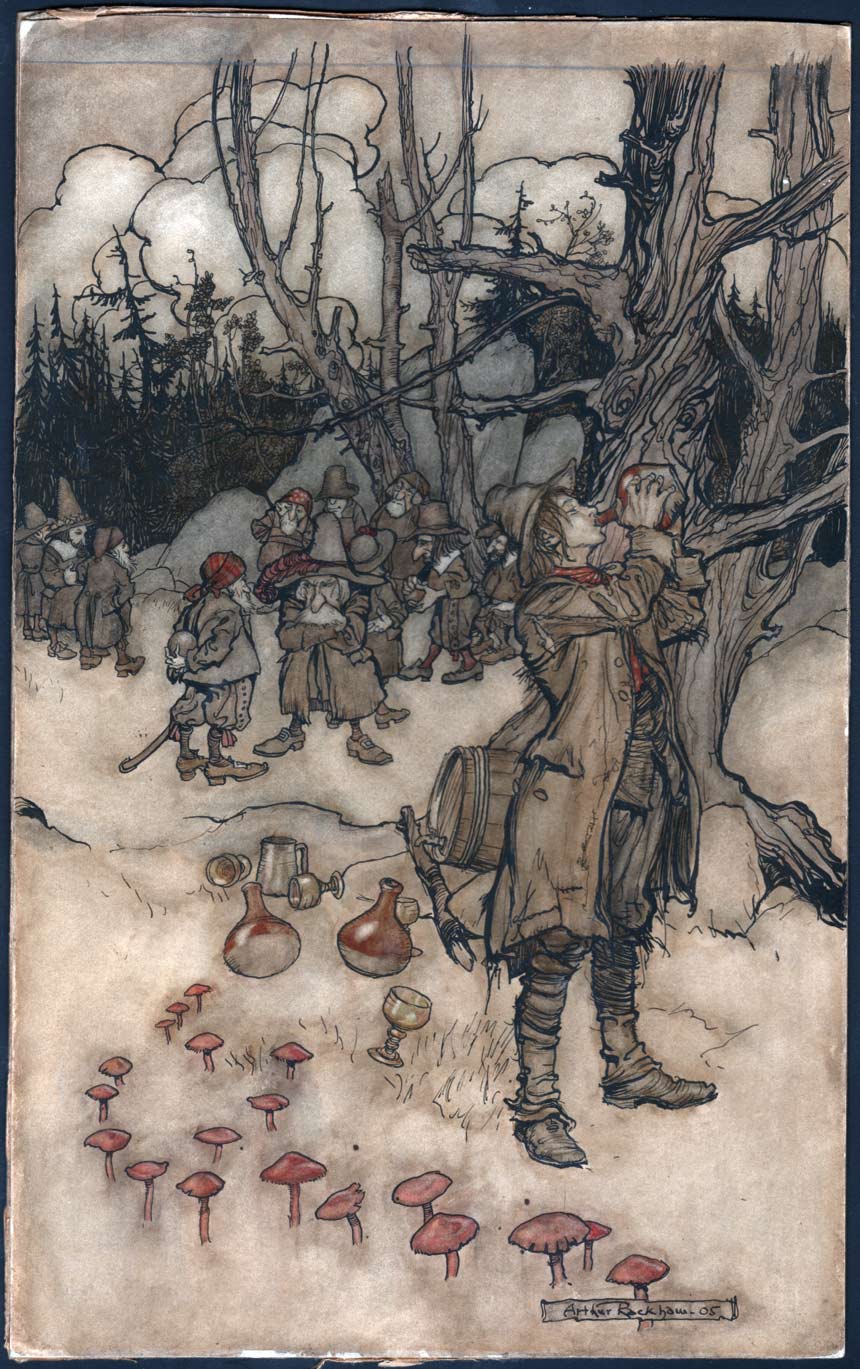

He answers in a heartbeat: an original manuscript of the children’s horror classic The Monkey’s Paw by English writer W.W. Jacobs, published in 1902. It’s got everything necessary to play havoc with a child’s imagination: a spooky curse, stormy night, gruesome death, mysterious knocks, and the gift of three wishes. “When it came up for auction at Christie’s, I was in tears. I just had to buy it!” said Karpeles, remembering the huge impact the story had on him as a youngster in Duluth. “At night, the street lamps would shine through the trees into my bedroom window. It looked like there was a ghost on the wall. It scared the hell out of me. But The Monkey’s Paw was about people being terrified by something which was really just a shadow, just like my shadow. After I read it, I was never afraid again.”

At one point, Karpeles decided to republish The Monkey’s Paw, complete with the original handwritten pages he’d acquired. He and his wife were invited to the ceremony

commemorating W.W. Jacobs’ London home with a blue plaque, Britain’s prestigious historic designation. Also on hand was none other than Prince Charles, in part because his Institute of Architecture was then housed in the building, and also because that’s the sort of thing princes do.

As Karpeles awaited his royal handshake in the receiving line, he thought it would be nice if the prince acknowledged his wife in the crowd. Good concept. Bad execution. To get the prince’s attention, Karpeles innocently reached out and put his hand on the prince’s shoulder. What he got, instead, was the attention of the prince’s no-nonsense, unsmiling, well-armed bodyguards. And he got it in a hurry.

Fortunately, after a quick explanation, Karpeles was forgiven, his wife was acknowledged, an international incident was avoided, and all without gunfire.

No harm. No foul.

Looking back, Karpeles still laughs about it.

And as for looking ahead? With 14 Manuscript Libraries up and running, will there ever be a 15th?

David Karpeles says no, “… although if someone tells me there’s a beautiful building in some city, I probably won’t be able to resist taking a look at it. I have a sickness that way.”

A sickness that began more than a million manuscripts ago, all because of Thomas Jefferson’s fifth-grade penmanship.

Good thing Jefferson didn’t text.

This article is from the November/December 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.