College Football: My, How the Rules Have Changed

Think you’re tough? How long would you last in a college football game playing 1890’s rules?

The first intercollegiate football game—played November 6, 1869, in which Rutgers beat Princeton, 6 to 4—bears little resemblance to a modern version of the game.

This “prehistoric” football was a hybrid of existing sports that combined the rules of soccer and rugby in a more physical, more dangerous game.

Today, we can debate whether modern football is too violent for college students, but there is little question about the 19th century version. Then, it was a harsh, brutal sport which became so hazardous that, during the 1905 season, 18 college players died from injuries sustained on the football field.

President Roosevelt considered outlawing the sport that year. Instead, he ordered colleges to impose rules to make the game less lethal. Since then, football has changed continually. As talk show host Cenk Uygur observes, “There is no tradition of football, outside of change. The game has changed countless number of times. The shape of the ball has changed; the number of people who play has changed; the tackling and blocking rules have changed; the forward pass itself is a change to the rules; and how many yards you needed for a first down changed.

Trivia tickler: How many yards did you need for a first down when the game first started? None, you just had to keep possession; teams were known to sit on the ball for a whole half.

[To read “How Teddy Roosevelt Ended Unfettered Football and Saved the Game,” click here.]

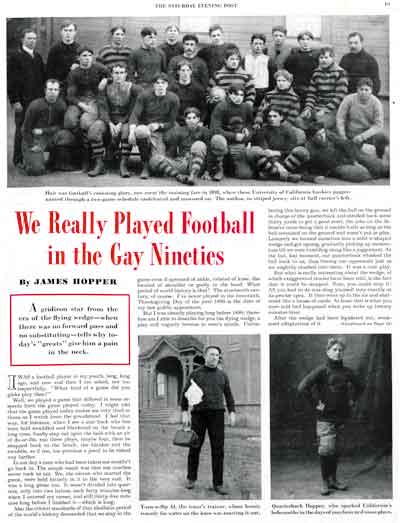

In 1945 James Hopper wrote for the Post about the game he played when he was quarterback for the University of California in 1899. Reading his account, you realize how much more the words “contact sport” could mean.

“I was already playing long before 1899; therefore am I able to describe for you the flying wedge, a play still vaguely famous in men’s minds.

by James Hopper

November, 1945

“Unlimbering this heavy gun, we left the ball on the ground in charge of the quarterback and strolled back some thirty yards to get a good start, the joke on the defensive team being that it couldn’t stir as long as the ball remained on the ground and wasn’t put in play. Leisurely we formed ourselves into a solid v-shaped wedge and got going, gradually picking up momentum till we were rumbling along like a juggernaut. At the last, last moment, our quarterback whisked the ball back to us, thus freeing our opponents just as we mightily crashed into them. It was a cute play.

“But what is really interesting about the wedge, of which exaggerated stories have been told, is the fact that it could be stopped. Sure, you could stop it! All you had to do was sling yourself very exactly at its precise apex. It then went up in the air and shattered like a house of cards. At least that is what you were told had happened when you woke up twenty minutes later.

“There being no forward pass, and hence no fear of a forward pass, the team on the defense lined up tight, its line a solid wall, its backs close up. When you lowered your head- and bucked that, you bucked a fortification. You had help, though. The help was not so much ahead, in the form of blocking, as it is today; it came from behind. As you bucked, your whole team massed at your tail and enthusiastically shoved you through. Through you went like a straw driven through a fence by a Middle West cyclone.

“Once through, even then it wasn’t as it is today. You couldn’t call the thing off by touching one knee to the ground as the modern back does. Touching the ground with the knee didn’t count. Also the ethics of the period demanded that you continue. Even asprawl you went on, clawing the earth for a possible half inch, spinning like a firecracker, twisting like a worm, crawling like a snake, while the fellows on the other side piled up on you one by one, and your own fellows, trying to help, piled up on you one by one, so that when the referee, a skeptical fellow, at last became convinced that your progress was truly halted and blew his whistle, you were established beneath a mountain of pigskin stalwarts with arms and legs sticking out like the guns of a battleship.

“Under there you lay very quiet, knowing that this was the only kind of rest you got in this game, holding your breath because there was no breath to breathe, tucking your hands under you to escape the prowlings of still ambitious cleats, and holding the ball tight in your armpit, for always, at that time, some sly sucker would be trying to steal it from you.

“In my last game we had in our equipment a maneuver that deserves special description. We called it the Kangaroo and it was built about our fullback, a rangy customer named Pete, who was fast and springy. As the center snapped the ball to me, Pete would already be on his way toward the line at a deceptively careless trot whose every step, as a matter of fact, had been carefully calculated. I handed him the hall as be reached a certain spot, also accurately predetermined, and he then leaped up into the air. This was all he had to do—leap up into the air. For at the same moment, I grabbed the seat of his pants, and gave a mighty upward heave while the two halfbacks grabbed each a thigh and gave a mighty upward heave. High through the sky Pete went sailing, to alight well behind the enemy line.

“The only inconvenience about this play was that, landing on the other side, Pete landed entirely alone. Before our protective intentions could get to him, he usually had been well worked over already by an irritated foe who questioned the honesty of this sudden arrival out of the air.”

Read the full article. It’s a fascinating and hilarious account of life on the scrimmage line before modern-day regulations made football both less lethal and more interesting.