Considering History: Robert E. Lee, James Longstreet, and the Truths of Civil War Memory

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

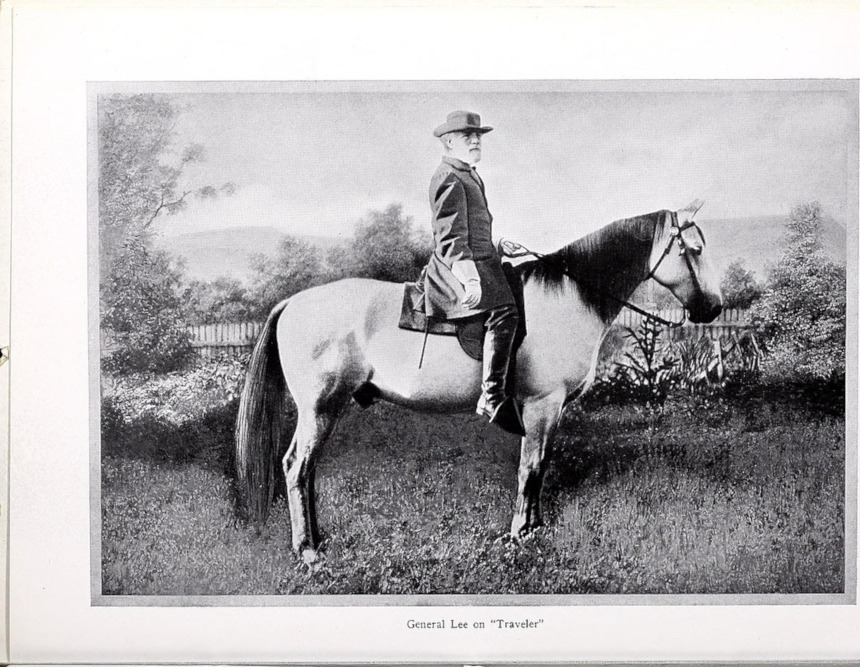

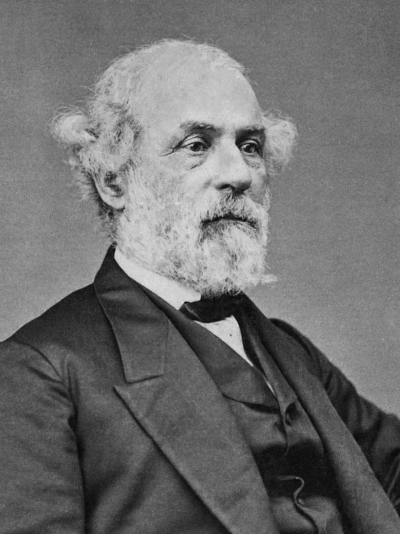

Growing up in Virginia, the Civil War was my gateway to a lifelong love of all things American history, and as a youthful Civil War buff, General Robert E. Lee was my idol. Even at a young age I certainly understood that the Confederacy had fought for a profoundly ignoble cause, and that the war’s outcome had been a just and necessary one. But I nonetheless embraced every element of the Lee mythos: the U.S. Army veteran who reluctantly joined the cause in solidarity with his home state but recognized the evils of slavery; the sensitive soul who declared (during a victory, the Battle of Fredericksburg) “It is well that war is so terrible, otherwise we should grow too fond of it”; and most of all (to a kid obsessed with military history and battle maps) the brilliant strategist who ran circles around the Union Army’s lesser military minds for much of the war.

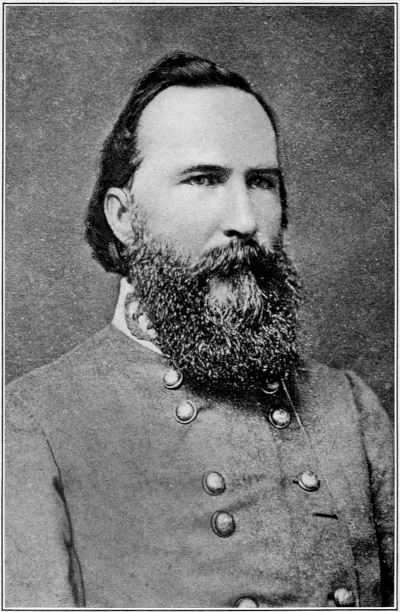

That last element in particular led me to a concurrent youthful disdain for General James Longstreet, one of Lee’s chief lieutenants throughout the war and yet a frequent dissenter from Lee’s strategies. That seemed particularly to be the case at the pivotal battle of Gettysburg, when (the story went) Longstreet’s disagreements with and deviations from Lee’s plans contributed to the Confederate loss. Yet whatever the details of that controversial military moment, the broader historical reality is both distinct and crucially telling: the deification of Lee and demonization of Longstreet reflect not military history at all, but instead the postwar and ongoing development of Civil War Memory.

Although Lee (1807-1870) was fourteen years older than Longstreet (1821-1904), the details of the two men’s careers through the Civil War are remarkably similar (and echo those of many other Civil War officers on both sides). Both graduated from West Point when they were 21 years old, both fought in the Mexican American War and received attention and acclaim for their service in that 1840s conflict, and both continued to serve the U.S. armed forces in multiple roles between that war’s conclusion and the Civil War’s outset. Both men were apparently uncertain about secession, not least because of those continued connections to the U.S. military; but both joined the Confederate Army in its first months of existence and would become two of its most prominent leaders throughout the war.

It was after the war’s end that the two men’s stories — and especially the collective perceptions and memories of them — would diverge much more fully. Lee died just a few years later, in 1870, but by then the national deification process traced in historian Thomas Lawrence Connolly’s The Marble Man: Robert E. Lee and His Image in American Society (1977) was already well underway. Those kinds of idealized tributes to Lee ramped up significantly after his death, leading Frederick Douglass to lament such “bombastic laudation” and “nauseating flatteries” to a man who “was a traitor and can be made nothing else.” But Lee was indeed made over the next few years into something quite different, the iconic hero celebrated in texts like Mississippi lawyer and author James D. Lynch’s epic poem Robert E. Lee, or, Heroes of the South (1876).

Other than Douglass, one of the few prominent late 19th century voices to resist this deification of Lee was none other than James Longstreet. In his 1896 memoir, From Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the Civil War in America , Longstreet sought to set the record straight about both specific events such as the Battle of Gettysburg and the overall national celebration of Lee as the war’s unquestioned genius. After quoting Lee’s reflections on the outset of Gettysburg’s third and final day of fighting, Longstreet writes simply, “This is disingenuous,” and the phrase sums up a good deal of his critique of both Lee’s memories and the collective memories of Lee. Although he does so in the respectful tone due to his commanding officer, Longstreet consistently creates a far different and much more critical picture of Lee and the war. For example, Lee opens his account of the night before that crucial third day by claiming that “the general plan was unchanged” and “Longstreet … was ordered to attack the next morning”; Longstreet counters that Lee “did not give or send me orders,” and so “in the absence of orders,” Longstreet had to utilize his own scouts and develop his own plan for the start of the next day’s (ultimately disastrous) attacks.

It would be easy to identify those critiques as the source of the neo-Confederate vitriol directed at Longstreet in the postbellum era. But the truth is that long before he published his memoirs, Longstreet had become a target for such hatred through his post-war actions, and specifically through his embrace of African American rights during and after Reconstruction. Longstreet joined the Republican Party, endorsing his friend (and Lee’s most formidable wartime adversary) Ulysses S. Grant for President in 1868 and taking on vital Reconstruction roles such as commander of all federal and state forces in New Orleans in 1872. In that latter role he commanded armed African American troops against a white supremacist militia at the city’s 1874 Battle of Liberty Place, when more than 8,000 men of the anti-Reconstruction White League sought to challenge and overturn a Louisiana gubernatorial election.

These Reconstruction conflicts comprised battles over America’s present and future but also over Civil War memory. Longstreet likewise resisted the era’s embrace of the Lost Cause narrative and its attempts to reframe the Civil War’s causes and meanings, at one point remarking to Grant, “I never heard of any other cause of the quarrel than slavery.” Yet the Lost Cause narrative came to dominate the postwar period so much so that by 1888, author Albion Tourgée wrote that American literature and culture had become “not only southern in type, but distinctly Confederate in sympathy.” And just as those national neo-Confederate sympathies made Lee into a marble man, they made Longstreet into at best a failure and at worst a villain.

By the early 20th century, that process was complete, as reflected clearly in my hometown of Charlottesville, which in the late 1910s and early 1920s famously constructed its statues of Robert E. Lee and his now favored (and more clearly white supremacist) lieutenant, Stonewall Jackson. As I grew up in Charlottesville half a century later, it’s no wonder that this marble tribute to Lee helped cement his iconic status in my youthful Civil War Memory, and helped push Longstreet further to the fringes. Whatever happens to those two statues or any of the other Confederate memorials around the country, it’s long past time we collectively revisit and revise our memories of both these men and the racial and national images they symbolize.