North Country Girl: Chapter 53 — Hello Groucho, Good-bye James

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

Even though I was working semi-steadily, I didn’t offer James money. It was never a relationship between equals; my piddling and erratic modeling checks for $90 or $225 would not have made a dent in his problems, only blasted out a hole in his pride.

I was stashing my get away money in case the worst happened, whatever that might be. Maybe James would rob a bank, or kill himself, or go back to selling Cadillacs in Des Plaines. When I moved in with James he was fun, generous, exciting. Now I was living with a hollow man and insanely hoping that the old James was not gone for good.

The market fell, and then continued falling. James turned into a zombie, a zombie who was now having trouble scraping up enough money to pay the rent. I came home one day to a pink “Late Payment” notice shoved under the door, which I placed on the coffee table; it went unmentioned and unmoved.

When James had cash in his pocket, it came from his backgammon winnings. The backgammon club was the only place James went at night; there were no more meals in nice restaurants or disco dancing at Faces. The last night I was ever there, I watched James distractedly pat at his pockets while asking his opponent if he would take his IOU. The winning player gently reminded James that the club did not allow IOUs, all bets were to be paid in cash or check. When James began lifting off his heavy gold chain, the man, whose only jewelry were onyx cufflinks, quickly demurred, murmuring, “Just this once.” After that I couldn’t bear to go back, and spent my evenings alone, pretending to be asleep when James got home, not wanting to know if he had won or lost.

At this point the stress unhinged me. I thought, “You know what will make things better, Gay? A dog,” though I had never had a dog in my life. I didn’t bother asking James, I just went to the closest animal shelter. It was filled with the sounds and smells of dogs, dogs who were locked away in row after row of cages, stacked to the ceiling, each dog looking more pitiable than the next. I was torn; they all looked so undesirable, all destined to be put down. A three-legged dog briefly stole my heart, before I saw the Dog Least Likely To Be Adopted: a hairless, toothless Yorkshire terrier with cataracts.

The pound guy told me that the Yorkie had been owned by an elderly woman who had barely been able to take care of herself and seemed to have completely forgotten that she had a pet; the dog, who would have been long in the tooth had they not fallen out from malnutrition, was recovering from a case of mange that left him mostly bald. I gave the pound guy $20 and he gave me the dog, who I named Groucho, along with a collar, leash and some canned dog food suitable for toothless dogs.

I guess Groucho had not been walked much; when I pulled on the leash, he lay down on his side so I had to drag him out of the animal shelter. I drug him a bit down the sidewalk, then realized I couldn’t do this all the way back home, so I picked him up and carried him. He weighed less than a loaf of bread.

James hated Groucho on sight, not that there was much to like. But Groucho may have been my guiding animal spirit sent to get me out of that awful situation. Pound guy had assured me that Groucho was housebroken; he did poop every time I took him out for a drag. But Groucho also pooped the second I left the apartment, varying where he left those little Tootsie Roll turds that James always managed to step in; if James made it safely out of the bedroom, there would be a tiny poop hiding in the white shag of the living room rug.

“This #$@%ing dog has to go,” James said. I agreed. I had to go with it.

My modeling career was puttering along well enough that I could rent a $140 a month studio, get the phone and electric hooked up, and furnish it from Goodwill.

James barely noticed as I packed my clothes and books and Groucho; he was riveted to bottom part of the TV where the stock market ticker slid along with its tale of woe. There was no steamy last kiss, no tears. I pecked his cadaverous, stubbly cheek and said “Goodbye.” “See you around,” said James. But he didn’t. We lived a ten-minute walk apart from each other, yet I never saw him again.

Groucho and I moved into our tiny studio on quiet, leafy Burton Place. Every day when I came home, Groucho would be sitting on my second-hand bed, waiting for me, his tongue lolling out of his toothless jaws. He never pooped in that apartment once.

I was landing enough modeling jobs that I had stopped having nightmares about being locked in a coat check. Almost every other month I had a solid week of work at the Chicago Convention Center, handing out brochures at the Furniture Show, running a towel folding machine at the Hotel and Restaurant Trade Show, and at the Auto Show, luring prospective car buyers in range of voracious car salesmen.

Ford Motor Company loved me; I had that beamy, fresh, All-American look, the look of a girl who belonged in the passenger seat of a Mustang. When they hired me I was sure they would put me in a pretty gown and stand me up on a revolving platform next to their newest model, and all I would have to do is grin and wave.

The man from Ford looked at the bevy of models assembled in the basement of the Convention Center, pointed at me, and said “You. You’re gonna be the magician’s assistant.”

He did not see an innate talent for sleight-of-hand; he saw a girl small enough to disappear inside a magic box.

Every car company at the Auto Show had some kind of come-on. Ford had a fifteen-minute magic show, every hour on the hour that brought families into the exhibit and kept the kids entertained while the salesmen swooped down on the parents. I didn’t even get a cute, sparkly magician’s assistant outfit; I wore a plain jane blue dress with “Ford” stitched in white. I stood next to the magician on the postage-stamp-sized stage and handed him scarves and hoops and held his top hat. For the final trick, I stepped into a black box, which looked like an upright coffin. The magician closed the door on me and intoned a few magic words while I scrunched down as fast as possible into the bottom of the box, pulling three mirrored panels away from the back and sides so they encased me in a tiny triangular space. The magician opened the door for a split second, the mirrors reflected the interior’s matte black paint, and poof! I had vanished. Cue applause. I sprung up, the coffin door opened, and I stepped out to take my own quick bow before I headed back out to the convention floor to pass out “Free Show: The Magic of Ford!” flyers.

The next year Ford had a different gimmick: Models, dressed in those same plain jane blue dresses, buttonholed all the grown-ups who walked into the Ford exhibit and asked “Would you like to win $100?”

“What’s the catch?” every suspicious attendee wanted to know.

“No catch at all! Here’s a raffle ticket. Find someone with the same number and you’ll both win $100!”

For the ten days of the Chicago Auto Show the Ford exhibit was complete pandemonium, as people dashed about comparing raffle tickets. Gangs of kids picked up tickets that had been tossed on the floor or begged grown-ups for theirs, and ran riot, yelling numbers at each other and anyone holding a small piece of paper. It was supposed to be for adults only and then only one raffle ticket per person, but it didn’t matter, you could take a thousand tickets and not win.

The game was as rigged as any carny con, and I was the shill, dressed in civvies almost as homely as those dresses by Ford. It was designed to get foot-dragging buyers on to a car lot to close the deal. When one of the salesmen had a hot prospect for a Family Truckster, he sent someone out to find me. My job was to approach the potential car buyers, ask them to read the number on their raffle ticket and then squeal “Wow! That’s my number too!” I immediately handed my ticket to the salesman; the prospects never realized there wasn’t really a match; they were too excited about winning. But instead of a crisp $100 bill, what the suckers got was a certificate in that amount. The $100 was waiting for them at their local Ford dealership. Before they could complain, I would gush, “Oh thank you so much! I can’t wait to go to Skokie Ford and collect my $100!” Then I dashed off and hid in the crowd until the next set of chumps appeared.

Trade shows kept me in Campbell’s soup, Groucho in kibble, and paid the rent, but were anything but glamorous. I spent eight-hour days standing on a concrete floor, next to adding machines or surgical supplies, trying to ignore my throbbing feet, looking as cute and approachable as possible, which was ninety percent of the job. The other ten percent was passing out samples or pins or pens or brochures, and fending off amorous salesmen and conventioneers, “C’mon honey, it’s just dinner. Put a little meat on those bones!” I turned them down with a nice girl smile, and gently removed their hands squeezing for either meat or bones on my butt.

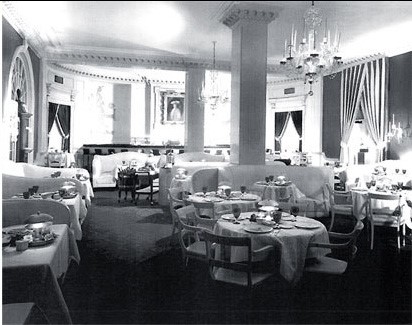

As much as I missed my brief former life of champagne cocktails and Dover sole, of being a regular in places where your drink arrives immediately and there’s a nice woman to hand you a towel in the ladies’, I had no desire to eat a chopped up steak at Benihana’s with the biggest manufacturer of stainless steel cutlery in America. I went home to soak my poor feet, heat up a can of tomato soup, and take Groucho out for a drag.

In June, the gigantic Consumer Electronics Show came to Chicago, taking over all three floors of the convention center and every trade show model in town. Sanyo hired me to pose next to a wall of car radios and lure buyers from Radio Hut and Pep Boys into the showroom. The guy in charge of the models taught us a few words of Japanese, none of which were useful in warding off the Japanese executives, who firmly believed that all of us models were hookers paid to entertain them, at the convention during the day and at their hotel at night.

On my first day, I was rescued from one small, insistent Japanese man by an American in a well-cut suit, who took the guy aside and spoke to him in Japanese. The Japanese man glared and shook his finger at me, and I prepared to be fired on the spot. But he walked away and my rescuer came over to talk to me.

“Sorry,” he said. “These guys have already been set up with girls, but Mr. Moto really likes you. I can’t promise he won’t be back. I’m Gerry,” and he stuck out a small, delicate hand. “When’s your break? Can I buy you a sandwich?”

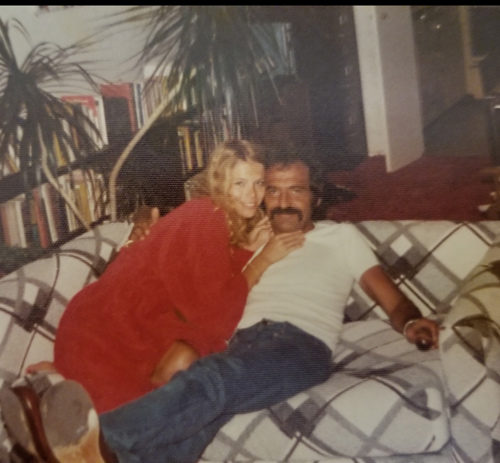

Gerry was just a few inches taller than me and as adorable as a cocker spaniel; he looked like a human Rowlf the Dog from the Muppets. He had soft curly brown hair that he wore just long enough to be hip and a funny little matching mustache that I knew would tickle. His eyes were a startling sky blue, innocent, almost transparent. I wanted to take Gerry home, put him on the couch next to Groucho and snuggle and pet the two of them.

Gerry wasn’t a salesman, he was an engineer who had come along on this Chicago junket in case a buyer had a difficult technical question about a car radio, which never happened, so Gerry just hung around the Sanyo exhibit, looking at me. I looked back and we both smiled.

A sandwich in the basement of the Convention Center turned into evenings out in those wonderfully expensive Chicago restaurants I had been missing. Sanyo gave Gerry a generous expense account, which he spent taking me out to dinner, after making sure that all the Japanese execs were happily set up with their hookers.

“Do not date guys you meet at the conventions,’’ my agent Ann had warned me. “It’s unprofessional and when it ends, poof, you’re out a client.” But Gerry was young and cute and I was tiring of Campbell’s tomato soup. I insisted that he not talk to me during the day, and after dinner I made him come to my apartment. I did not want to run into my Japanese suitor at the Hilton or have to do the El ride of shame at dawn.

Gerry was twenty-eight, and from California, which I thought automatically made you cool. He was funny enough and smart enough and smitten with me, which I always find attractive. He was a born tinkerer, one of those kids who reads Popular Mechanics cover to cover and takes apart every electrical appliance in the house. After being hired by Sanyo, he decided on his own to learn Japanese. Gerry taught me several interesting Japanese curses then warned me never to use them within earshot of the Sanyo executives. (I wish I could remember how to say, “You are a man who has to buy a sheep to service your wife” in Japanese.) The best part was that after five days, Gerry went back to California, leaving Groucho and me with a nice assortment of doggie bags from fancy restaurants.

I was pleased but not surprised when Gerry called to invite me to California for the Fourth of July. Summer is Chicago’s second worst season, when the sodden heat rolls off Lake Michigan accompanied by the smell of alewives, their fishy life cycle complete, dying and rotting by the millions on the shore. My sweet little studio was stifling; I would have gone anywhere that wasn’t a hundred degrees. The one girlfriend I had made, a model I met in an “Acting for Commercials” class (we bonded when we found out that the lech of a teacher had offered both of us free private tutoring, sessions that were very hands on) had married and moved to the suburbs. I didn’t want to spend the Fourth drinking cheap beer in Frank the photographer’s loft, which was as un-air-conditioned in the summer as it was unheated in the winter. I was hot and sticky and lonely.

I wasn’t in love. I wasn’t bedazzled as I had been with James. But I liked Gerry: he was cute, he made me laugh, and was okay in bed. So I said yes and Gerry sent me a ticket. I dozed on the plane out to California, dreaming of devouring hot dogs and hamburgers on the beach, gazing out at my old friend, the Pacific Ocean, and cuddling on a blanket with Gerry as a million fireworks exploded above our heads: a perfect Fourth of July.

North Country Girl: Chapter 51 — Big Pink and the Invisible Man

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

James and I were in his hated hometown of Winnipeg. He had been summoned there by Elena, the daughter he had deserted years ago. As a family reunion it was a disaster; James showed no desire to spend any quality time with his chubby, homely daughter, who was more introverted and tongue-tied at 22 then I had been at 15.

Having completed his obligatory visit with Elena, James rooted out his best friend from high school, Robert, whom he had heard was doing well financially, but not exactly through legal means. Luckily for James, his pal was not locked up in the hoosegow; he was currently out on bail waiting for his next court appearance.

I felt right at home as we drove through Winnipeg to Robert’s house; his neighborhood was almost identical to the middle-class one I grew up in: big red brick houses on spacious, carefully maintained lots shaded by tall pines and paper-barked birch trees. We pulled up to one of these stately homes. A pretty blonde woman invited us in with a tight, brittle smile, introduced herself as Robert’s wife, and led us into the living room where Robert was waiting for us.

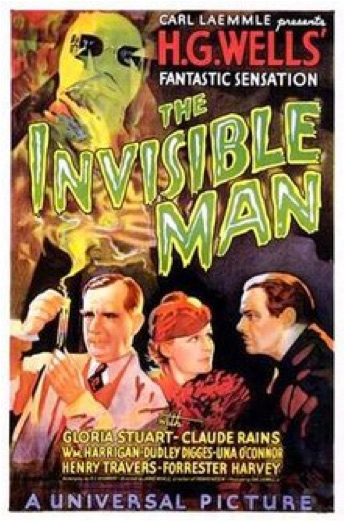

Robert’s head and hands were completely swathed in white bandages; he looked like Claude Rains in The Invisible Man. Where his face was supposed to be there were four holes poked out for eyes, nose, and mouth; his hands were oversized, slightly grimy gauze mittens. The charge he was facing was arson for profit. Robert may have been a successful criminal, but he had obviously completely screwed up this last job.

Robert’s nervous blonde wife brought out a round of Seagrams and Seven-Ups, my alkie grandfather’s tipple of choice but not mine; the rich, spicy, evocative smell of the whisky made me feel that I was seven years old.

Robert took his highball through a bendy straw, squeezing his glass between his stiff bandaged hands like a raccoon. James never asked “How’re ya feeling?” or “Oh boy, I bet that stung,” or made any reference to the fact that we were having a conversation with a man who didn’t have a face. Unlike sitting with someone who has a cast on their arm or leg, there was no humorous recounting of how Robert came to have these injuries. My own face twisted into a rictus of a smile as I tried to get through the inevitable small talk: where I was from, how I liked Winnipeg, how long the drive from Chicago had taken. I was relieved when the conversation turned to anecdotes of boyhood hijinks and whatever-happened-to’s, although I couldn’t seem to relax my face.

After they had exhausted the boring gossip about their old schoolmates, Robert said, “Hey, why don’t we all go up to my house on the lake for a few days?” I did not want to look at this talking mummy for another second, but James had already accepted, probably delighted to be out of the reach of his daughter.

In Minnesota if you had a place on the lake it was a homey cabin, with appliances from the 1940s, one or two bunkbeds in every room, musty furniture, a deck of cards with “two of clubs” scribbled on a joker, tangled fishing gear, and either electricity or indoor plumping, but never both. That was what I had pictured in my mind as we drove through the forest surrounding Lake of the Woods, catching glimpses of the shining silver water between trees. It all seemed so welcoming: the almost black firs contrasting with the gleam of white birch, the hand-painted signs posted at each turnoff with the owners’ names or the corny names of their cabins — “Dunmovin”, “The Oar House,” “Dock Holiday” — were all as familiar to me as breathing. I almost forgot that riding in the passenger seat in the car in front of us was a man with no face.

James followed that car when it turned at one of those signs, a white board with “In the Pink” neatly painted on but wanting a bit of touching up. James’s El Dorado bumped down a narrow dirt track towards the lake where we found not the rustic cabin I had expected but a sprawling modern white brick ranch. We walked into an immense living room with three sides of floor-to-ceiling windows that held all shades of sky and lake blue. Along the shore, the dark green forest was as perfectly reflected as if the water were a mirror. Next to one set of windows were twelve chairs surrounding a lengthy dining table. To the left I could see into a spacious, sleek kitchen. Robert had already told us, “Plenty of room! We’ve got four bedrooms, each with its own bath!”

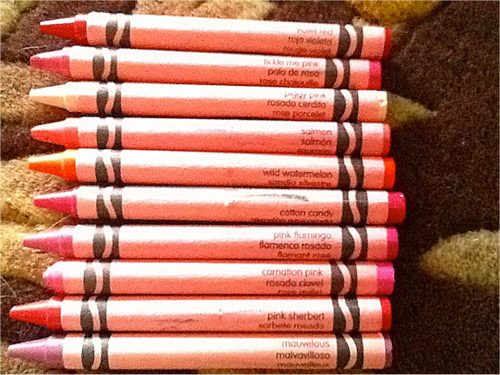

There was only one thing wrong. Everything inside the house was pink. Not just any old pink, but the exact shade of a carnation pink Crayola crayon. The sofa, the rug, the paint on the walls. The bathtubs and sinks. All the modern appliances in the kitchen. That big dining table and all the chairs.

Robert, raising his voice to be heard through his mask of bandages, showed us around, the proud owner of all that pinkness. “You wouldn’t believe the deal I got!” he boasted. When the woman who had owned and proudly decorated the house had died, there had been no other offers, and the heirs couldn’t wait to get that pink elephant off their hands.

It was like being in a brain, or an intestine, all that throbbing pink. As I soaked in the pink tub later that evening, I tried to imagine different scenarios for this obsession, but failed to come up with a likely story, as it was obviously just madness.

Not only was everything pink, everything was really nice. That tub was huge, the hot water inexhaustible. You sunk so deep and comfortably into the pink couches, all you wanted to do was sip a cocktail and gaze out the picture window at the lake. The wooden dining table and chairs were heavy and substantial, all painted and shellacked so they shone like a manicured nail. Where could you even go to buy a pink Whirlpool dishwasher? I wondered.

“You wanna see something funny?” Robert asked and led us down to the lake. There, at the end of the dock, deep in the water, under the flashing pike and drifting waterweeds, was a pink refrigerator. A salmon pink refrigerator. The wrong shade of pink. When it was delivered to the house, Mrs. Pink had freaked out and made the delivery men dump it in the lake. The big two-door refrigerator that was currently purring away in the kitchen perfectly matched the stove and the walls and the cabinets and everything else in the pink house.

“Some house,” said James. “How long have you had it?” Robert bought the house three years ago and hadn’t changed a thing. He didn’t see anything wrong with the interior, everything was first class, custom made, top of the line. So what if it was pink?

During the day I spent as much time as possible down at the dock reading or swimming or gazing out at the lake, trying not to think about James losing his fortune and his mind, his unhappy twice-rejected daughter, the bandaged arsonist with third degree burns, or the crazy house looming behind me. I lingered by the water till the loons started their plangent calls, the signal for swarms of enormous mosquitoes to descend and drive all humans inside, where three of us dined off pink plates at the huge table, Robert alternating between highballs and a disgusting looking liquid food sucked up through a straw.

James never mentioned his daughter Elena, and I certainly was not going to bring her up. He was restless as a chained wolf at that lake house; the Winnipeg Free Press did not carry even yesterday’s NYSE reports, and his requests for a New York or even a Chicago paper were met everywhere with disbelief: why would you want a newspaper from somewhere else? There was no TV at the lake house, Robert apologized, no reception out there in the north woods. James, not a lover of country life under the best of circumstances, cut our visit short. We said goodbye to that ranch house of insanity. James went to shake hands with our host, slapped him on the back instead, and we drove back to Chicago.

The news waiting for James was especially bleak. Highline shares were tumbling faster than ever. James spent the day yelling at the TV, trying to get his broker — who he now was convinced had intentionally dumped that piece of shit stock on him — on the phone, or staring into space.

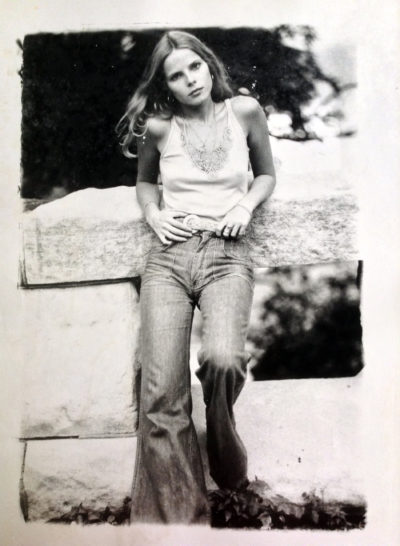

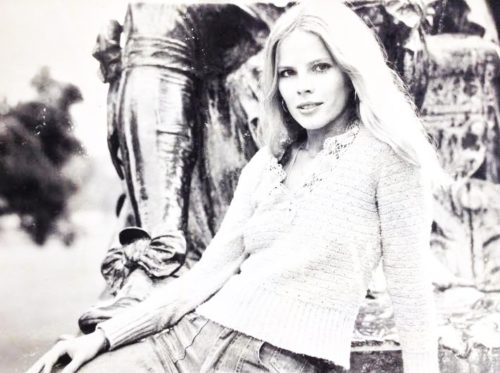

I needed my own money and had a harebrained idea of how to earn it. I was going to be a model. I had already made one commercial and earned $100, why couldn’t I do two or three commercials a week?

I didn’t have a copy of my Mexico commercial. I didn’t have any professional photos. And I topped off at 5’3”. When I showed up at the Ford Modeling Agency the receptionist gazed several inches above my head, where my face was supposed to be, then showed me the door. Ditto at Wilhelmina.

In the Chicago Yellow Pages I found a small ad for the Ann Geddes Modeling Agency, which turned out to be a waiting room with three chairs, an unoccupied receptionist’s desk, and a tiny private office where Ann Geddes, a former model herself, was waiting for me, along with her husband Silver, who was a stockier, grayer version of James, and who, true to his name, wore massive Navajo silver rings and bracelets and a silver hoop in one ear.

“When’s your birthday?” Ann asked.

“Oh, I’m twenty-one.”

“No, the date and the year and if you know it, the time.”

Having gotten that settled, I started babbling about my Mexico tourism commercial (leaving out that I had been the emergency replacement) and my acting experience in high school (leaving out that the experience consisted of three lines in “You Can’t Take It With You” and the co-star role in a student-directed one-act play).

Ann Geddes was ethereally gorgeous, with long, rich red hair and milky skin unmarred by a single freckle. Her beauty was not intimidating. She was as warm and friendly as an older sister; it was easy for me to rattle on like an idiot. Silver, who had been scribbling on a pad the whole time, interrupted my life story: “I’ve got it!” He was an astrologer; while I was trying to talk my way into being a model, he was casting my horoscope. He announced that despite my shortcomings, the stars were aligned and the Geddes Agency would be happy to represent me, their take ten percent of everything I earned.

This did not mean I would have steady work or a regular income. The star of the Ann Geddes Agency was another small blonde, who was a lot prettier than I was and had several commercials under her belt that she actually had copies of. When the call came in for a model to pose next to a refrigerator or power tool to make it look bigger, she was sent. I was the backup blonde.

I did not discover my second banana status until later. At the moment I was thrilled: I was officially a model. Ann blithely handed me a contract to sign and a Xeroxed contact list of every photographer in Chicago, from the newest Chicago Art School graduate to Screbneski. It was up to me to call on all of them, trolling for modeling work.

But before I could do that, I needed a composite, an eight by eleven calling card with a pretty head shot on the front and photos showing a range of commercial personas (young mom, career girl, sportswoman) on the back to leave with the photographers. Ann took a red pen and scrawled a circle around one name on her list.

“Go see Frank Wojtkiewicz first. He might take composite photos of you for free,” she said, her face as smooth and blank as a china plate.

North Country Girl: Chapter 50 — In Search of Lost Daughters

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

I had ditched James and the car of 1,000 Quaaludes, hoping that they would both make it to Chicago safely, and made my own escape to my family in Colorado, a family that now included a stepfather and a dilapidated ski hostel.

The flight from Denver to Steamboat Springs was in the smallest plane I had ever seen. My memory is that directly behind the pilot were four folding chairs welded to the floor that had been jerry-rigged with seat belts. We landed on a runway in a field and were told to grab our luggage, which had traveled in the cabin with us. I followed the pilot down the stairs towards a small brick building, where I could see my mom waving, and I sunk up to my ankles in mud.

Early spring in Steamboat Springs is mud season. The tiny town was tucked in a valley at the base of the ski mountain. All the snow on the hills and all the ice in the Rocky Mountain rivers had melted, and every square inch of the town that was not paved was a quagmire — and there were a lot of unpaved roads in Steamboat. In a few weeks, flowers and grass and trees would be in full blossom and leafy green, but now the place was a study in grays and browns, although all under the bluest of skies. Snow-peaked mountains were etched across those skies, almost too blinding to admire.

Steamboat Springs was rough and rugged, the anti-Vail; there was no comfortable, enclosed gondola to whisk you to the top of the mountain. It was a place where you skied in jeans instead of fancy designer outfits. It stuck proudly to its roots as a cow town, despite a smattering of hippies living in communes, hippies who were detested by the ranchers and tolerated by the skiers, and who were known to swim naked in the hot springs.

My stepfather, Jerry, had bitten the bullet. He married my mom, sold his postage stamp ranch outside of Denver, and after casting about for new business ventures, bought the Haystack hostel, which he was trying to fix up all by himself in time for the next ski season. Once again, my younger sister Heidi had been uprooted, right after she had finally made her one and only friend at her hateful school. I knew my mom was furious with disappointment. She had imagined that as the second Mrs. Jerome she would be the hostess at an elegant restaurant like the Highland Supper Club Jerry had owned back in Duluth, not checking in unwashed young ski bums at a hostel. I thought I could read the whole tale from the three thick furrows in her brow.

Once I was mud-free and shoveling down a hot homemade meal, my mom sat down across from me and said, “Lani is missing.” My seventeen-year-old sister, a newlywed of less than a year, had run away from her husband Mitchell. “But I know where she is.”

A few weeks before, Mitchell called my mom to say that Lani was acting crazy, she was out of her mind. He didn’t know what to do, but since he had to go to work he had tied Lani to a chair for her own good. Then he hung up.

Mom said, “I thought, I have to go rescue her right away and I was frantic looking for my purse and car keys and the phone rang again.” This time it was Lani; she had freed herself from the ropes and called to say that she wasn’t crazy, she had told Mitchell she was leaving him. He had been routinely beating the crap out of her.

“Lani told me not to drive down. She was going right away, before Mitchell came home. And then she hung up and that was the last I heard from her.”

“And you couldn’t tell me this when I called?” I asked through a mouthful of mashed potatoes. I don’t know what I would have done differently, but I couldn’t believe she hadn’t told me any of this when I phoned her from Texas to let her know I was on my way.

“Well,” said my mom, “there is a second part to the story and I wasn’t sure if you would come here if you knew it. I’m driving to California to look for Lani.”

Over the Easter Break, mom had driven Heidi back to Colorado Springs to see her sorely missed friend from her old school. “I drove by that psychic, the one who helped grandma Nana find her Black Hills gold bracelet a few years ago.” (After glancing at my Nana’s humongous handbag, the astute psychic told her, “I can see it…you will find the bracelet in a purse.” And grandma did.)

“Something told me to go in and see the psychic and she held my hands for a minute and said Lani was living in Los Angeles.” My mother was going to track down her runaway daughter.

Not only that, when my mother revealed her plan to her own mother, grandma Nana instantly volunteered to join the search and was flying in the next day.

Less than 48 hours after I had arrived in Colorado I was off on another cross country car trip, sharing the driving with my mother while my sister Heidi stared glumly out the window and my grandmother read every passing road sign aloud: “Stuckley’s Pecans. Roy’s Big Boy. Bluebird Motel. House of Pancakes. Mystery Spot. Philip’s 66. Candy and Cones. Hole in the Rock. Cowboy Corral Steakhouse…”

For the long western miles where there were no road signs, my grandmother criticized the driving skills of whoever was behind the wheel, despite never having learned to drive herself. When she thought of it, which was several times a day, grandma Nana hollered, “Gay Lynn! Gay Lynn! How can you drive without your glasses!” refusing to believe in the effectiveness of contact lenses.

After a long signless stretch of road in Utah, we abandoned grandma at a gas station in Green River. We decided twenty minutes was long enough to teach her a lesson. When we returned there was grandma standing forlornly outside the ladies, quivering and clutching her enormous purse. There was no more back seat driving, but the out loud sign reading was unstoppable, and went on till California, where we unloaded grandma Nana on a second cousin living in Loma Linda.

The entire extent of my mother’s plan was that she would spot Lani somewhere and take her back home. All mom knew of Los Angeles was Knott’s Berry Farm and Disneyland; so we searched those places first, in between going on rides and eating boysenberry pie. Lani was not there or anywhere else we went in Los Angeles. After a few days of driving around the sprawling city, my mom sighed, told me to get out the road map, and we headed back to Colorado.

(Lani actually was in Los Angles when we were looking for her. After she freed herself from the chair and made that phone call to our mom, she grabbed a few things and hit the road, hitchhiking west. She found a job peddling office supplies over the phone and within a year was their top sales person.)

Once we were back in Steamboat Springs, I realized I couldn’t stay in that unhappy house, with nothing but mud outside and miserable people inside. My stepfather was dismayed by all the things that were wrong with his new property, most of which had not been pointed out by the seller. My sister Heidi hated her new school and pined for her friend back in Colorado Springs. My mom cycled through a sullen resentment towards her new husband for dragging them up to this muddy cow town, murderous rage at my sister’s abusive husband, and loony plans to drive four hours down the Rocky Mountains to see if the psychic could pin down Lani’s exact location in Los Angles. I made my goodbyes and flew off to Chicago and James.

It was a subdued James who picked me up at O’Hare and greeted me with a distracted peck. Wow, his portfolio must have really gone to hell, I thought, looking up at the departure board and thinking of new escape routes. James waited until we were in the Cadillac, where he could face the road and not me, and said, “I got a phone call from my daughter. She wants to meet me.”

I had managed to bury the fact that James had a daughter a year older than me so deep that it was like hearing it for the first time. Now she became very real, a third presence in the car.

“There’re a couple of guys in Winnipeg who knew I was in Chicago and Elena” —-now the daughter had a name—-“Elena called all the James Rodgers till she found me.”

All her life Elena had begged and begged her mother for information about her father. Her mother finally gave in, revealed to Elena the names of her father’s friends who might know where he was, and then died.

James looked as grim as death himself. I asked, “What are you going to do?”

“We’re driving to Winnipeg. We’re leaving tomorrow morning.”

I didn’t even bother to unpack my pink Samsonite suitcases, just wiped the mud from the Steamboat Springs airport runway off. The next morning was the start of my third road trip of the year, Chicago to Winnipeg, once again on the trail of a lost daughter.

After his escape from a shotgun wedding, James had never returned to Winnipeg, not even for his own parents’ funerals. He dismissed it as provincial, narrow-minded and boring; Winnipeg was everything James was not. I suspect he was also worried if he went back he could still be forced into marriage to the mother of his child. But now that woman was dead, and the daughter he had left behind twenty-two years ago wanted to meet her dad.

We headed north, driving and driving through the night, until the front right tire ran over something with a thump and startled James awake. “I think you hit a cat,” I said and took the wheel.

We found a hotel in Winnipeg and I collapsed into a now all-too-familiar post-driving exhaustion coma. I woke up to see the latest incarnation of James: quiet, unsure of himself, and far less attractive, staring at the phone. His hand hovered above it, then went through the motions of picking up the receiver and putting it down a few times before he cleared his throat, lit a cigarette, and called his daughter.

Elena wanted to come over to the hotel right away; James put her off, saying he wanted to take her out to a nice dinner. Elena was unable to come up with the name of Winnipeg’s finest restaurant. “No, not a Howard Johnson,” James told her, “I’ll find out and call you back.”

A few hours later, the three of us were at that nice restaurant, sitting in a big red booth, staring at each other. Elena had not expected her father to bring his young girlfriend to this momentous reunion. I almost wished I were still stuck in the mud in Steamboat Springs.

Elena, a year older than me, could have passed for fifteen. Her round, open face, at least the part that wasn’t hidden by her frowsy bangs, was unmarked by experience. She had inherited James’ dark coloring, with a sallower cast, but none of his handsome Mediterranean features. She was solid and stumpy, her hands were baby-like and dimpled, with fingers like Vienna sausages. I could tell James was horrified. It was coming off of him in waves, like stink.

It was a small tragedy played out over vodka drinks for James and me, root beer for Elena. She wanted to be hugged and fussed over. She expected deep apologies, tears, and promises of undying love from then on. What she got (besides the increasingly drunk girlfriend) was James in his car salesman persona: friendly, bursting with advice, and gone tomorrow. He kept up his patter, as Elena had no conversation.

Elena didn’t work, hadn’t been to college. She was as ignorant of the world outside of her hometown as I had been as a seventeen-year-old in Duluth. She had always lived with her mother, who had left her a little bit of money. She guessed that she would now get a job but had no idea doing what.

James was a snob and judgmental and the center of his own universe. He looked at his daughter and saw nothing of himself in her, and so she meant nothing to him. Maybe if she had been thin, or pretty, or smart, or even slightly inquisitive about the world outside Winnipeg, James could have found something to attach himself to. I was caught between this poor girl’s desperate longing for a father and James’s desperate desire to get the hell away from this person who claimed to be related to him.

The literal icing on the cake was when Elena ordered dessert, something James believed only fat people with no self-discipline did. When it arrived, James got up, announced that I was tired after our long drive, peeled off a couple of $100 bills and stuck them under the cake plate, and called for the check. “We’ll be in town a few more days,” he told Elena, her fork halfway to her mouth, her cow eyes downcast. We never saw her again.

North Country Girl: Chapter 49 — We Turn Outlaw

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

It was time for James and me to leave Mexico and drive back to Chicago. We were far from the gilded, blithe couple of the year before. James now actually looked at bar and restaurant tabs before paying them. The value of his heavily leveraged stock portfolio had plummeted; he was desperate for ready cash.

James had a doctor in Acapulco who wrote him legal prescriptions for Quaaludes. We had gone to see him together the day after we arrived, so James could apologize for his failure to get the doc a gun. A thick layer of dust covered everything in that dingy, one-room medical office, but there was nowhere to sit down anyway. The place stank of body odor and old cigar. James’s doctor was an elderly, bald, and short, his face and skull covered with constellations of brown age spots. Dr. Lude leered at me while kicking his legs about his chair, like a four-year-old at a birthday party. When James tried to push me closer to this hideous imp, I arched my eyebrows in an are-you-kidding look. James shrugged and peeled off twenty dollars from his ever-present roll of American money. Prescription and bill were exchanged, and we headed to the pharmacia next store.

Now, on our last morning in Acapulco, James took off in the Cadillac without a word while I packed up my pink Samsonite. When he returned he announced that he had made one last visit to see his doctor. I wasn’t surprised. I expected that James would want to bring back Quaaludes for himself and to dole out to pretty cocktail waitresses to demonstrate what a cool guy he was.

“Look here,” said James; and there was the glitter and the grit of the old James in his eyes as he handed me his new prescription. I couldn’t decipher the scrawled Spanish, but I clearly saw the number 1,000.

“A thousand Quaaludes?”

James’s doctor had told him that was legally the maximum number of Quaaludes he could prescribe. This obliging doctor also told James that he should fill his prescription at the Rorer factory outside Mexico City, since no local pharmacia carried 1,000 Quaaludes. Quaaludes were forty cents apiece in Mexico. James believed he could sell them in Chicago for four or five dollars a pill.

James claimed that because he had a prescription, possession of Quaaludes, even in that amount, would not be illegal in Mexico. He had also worked out where to hide 1,000 Quaaludes in the Cadillac.

I had been dreading the drive back, the horrors of the Mexican highway, the days filled with cigarette smoke, cassette tapes I never wanted to hear again, and too little food, the nights trying to sleep sitting up. But my heart lifted a little at any reappearance of the old James, even one with such a crazy, pill-in-the-sky dream.

We drove out of Acapulco, James beaming at his cleverness: “The ludes have to be even cheaper than forty cents at the factory. In Chicago, they were at least five dollars apiece when we left. I bet I can get six dollars now.” Not for a minute did I believe that James would be able to buy that many ludes, but for James, that four or five thousand dollars he was going to make was as real as if it were already in his pocket.

We reached Mexico City that evening. James navigated the maze of highways and cobblestone streets to the Zona Rosa, pulled in front of a wedding cake of a hotel, and handed the keys to a waiting valet. James popped for this lovely hotel room and a real dinner, something I had not enjoyed for days. He was preening; he felt he was in control, on the verge of a big score that was even more satisfying because it was illegal.

The next morning, a helpful man at the front desk gave James directions to the industrial suburb where the Rorer factory was, and we were off on what I was sure was a wild goose chase. Within an hour, we pulled up to the gatehouse in front of the immense steel grey factory, distinguished from the surrounding buildings and warehouses by a giant RORER sign. A guard left his post to peer into our car and James whipped out his prescription as if he was showing it to a Walgreen’s pharmacist. The guard shrugged, raised the control bar, and waved us through. I felt a squirt of panic in my guts. We parked; James left the air conditioning and the Mexican radio running for me while he strolled into the building.

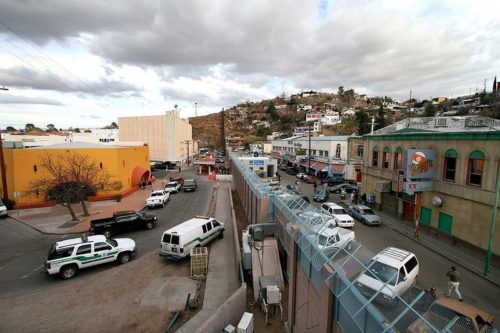

I had finally managed to calm myself down when the dark tinted front door swung open and James appeared carrying several cardboard boxes, one stacked on top of the other, a tottering tower of pills. “Pop the trunk,” he called out. With 1,000 ludes in the back of the car and me without a thought in my head that I could bear thinking, we drove and drove through Mexico north, finally stopping at a rundown motel in the border town of Nuevo Laredo.

The motel did get American TV, and I spent hours flipping channels, trying to find something to take my mind off the fact that James was busy finding hiding places for a 1,000 Quaaludes in the Cadillac. Whenever I looked out the greasy motel window he would be under the car or disassembling the trunk. James did know his cars. He also thought he knew border crossings well enough to get away with this.

“There is nothing to worry about. The Border Patrol is looking for pot and heroin, not pills,” he said. “There’s been no pot in the car. They can bring in the dogs, there’s nothing for them to sniff out.” And of course, he reminded me, he did have a legal prescription. We were perfectly safe.

James was a degenerate gambler. As he always did while in the midst of a big game, James doubled his bet. At some point while I was watching re-runs of Star Trek and The Mary Tyler Moore Show, James had not only stuffed 1,000 ludes in the Cadillac, he had found someone at the motel to sell him a pound of weed, and made a trip to a hardware store for roll of duct tape.

James put the pot and tape in a brown paper bag, took off his gold chain, ransacked my suitcase for the plainest dress I owned, and told me to swap my contacts for glasses. Thus disguised, we went into the motel office, where James put a five-dollar bill on the counter, asked the startled clerk for the name of the best restaurant in Laredo, on the American side of the border, and to please call a cab to take us there.

The taxi, a rusty and rattling Volkswagen Beetle, came, we hopped in, and James shoved the bag of pot under the back seat. James had become an overnight expert on drug smuggling, always the self-taught man.

“If we’re stopped and searched, and they find the pot, we’re in a cab. A cab is a public conveyance, they can’t prove it’s ours, anyone could have left it there,” as if forgetting a pound of marijuana in a cab were as common a misplacing an umbrella.

At the border crossing, a bored official asked the cab driver where we were going and then waved us through, not even looking in the back seat or asking for our passports. James reached under the seat for the brown paper bag, put it in my purse, and gave me instructions.

It was a nice restaurant. Too bad I couldn’t swallow a bite. While James paid the bill and called a cab to take us back across the border to Mexico, I went to the ladies’ room, locked the door, and got down on my hands and knees under the sink. I took the tape out of the bag, and attached the brown bag to the top of the drain pipe, winding the tape around and around. I crawled back out, stood up, craned my neck from a bunch of angles to make sure nothing was visible under the sink, brushed off my legs, washed my hands, tossed the rest of the tape in the garbage, and went out to where James and the cab were waiting.

The next day, we put on the just-plain-folks clothing from the night before, trying to look as innocent as a twenty-one-year-old blonde and a swarthy forty-three-year-old man in a new model Cadillac El Dorado coming back from Mexico could look. I suggested buying some souvenirs to make us seem even more normal, but the newly expert James said that would draw attention to us: too many people tried to smuggle drugs in piñatas and marionettes.

We looked suspicious enough for the border patrol to give us their full attention at the crossing. We politely stepped out of the car when asked, James opened the trunk and all our suitcases, I dumped out the contents of my purse. The guards walked away for a little conference while James smoked a cigarette. I sweated and had to pee and made up my mind that if we were busted, I would claim that I was a simple Minnesota country girl, being held against my will and forced into a life of deviance and drug smuggling. I practiced crossing my eyes; I could say James was keeping me doped up on those Quaaludes…

“Okay, sir, you’re free to go. Have a nice day.” And with that, we were back in the U.S., with 1,000 Quaaludes somewhere in the Cadillac and a pound of pot to pick up. We stopped at the restaurant from the night before, where James ordered two coffees. I reclaimed our pot in its brown paper bag from under the ladies’ room sink, and we were back on the road.

We had gotten away with it, but our thirty-minute encounter with the Border Patrol had undone me. James was rubbing my leg and complimenting me on keeping my cool, and I was running through everything that could still go terribly wrong. We were in Texas, where the Caddy’s license had already been flagged for guns and white slavery. We had a carload of illegal and semi-legal drugs. And we had thousands of miles and a bunch of other god-forsaken states to cross before we safely home on Oak Street.

My mind suddenly snapped into focus: I told James I needed to go see my mom in Colorado. Like right away. James shrugged and said he didn’t mind doing the rest of the drive by himself. We had been together non-stop for months and needed a break from each other. James pulled into the next rest stop and I called my mom from a pay phone; a recorded message told me that number was no longer in service and gave me a new one. I dialed that one, my mom picked up right away, and I discovered that my mother and her new second husband had moved to Steamboat Springs, where they were renovating a run down ski hostel called the Haystack. I mouthed a silent “shit.” I knew that rathole; I had stayed there once on a ski trip. My mom didn’t have much of a reaction to my announcement that I was coming to visit and didn’t comment on how strained and anxious I must have sounded.

James drove me to the Dallas-Ft. Worth airport, where I bought a ticket to Denver and then onward to Steamboat Springs. A last night together in a real motel with working AC and clean-smelling sheets made me cautiously optimistic that we had gotten away with it. I was almost relaxed, now that I had planned my own escape and James was crowing. No lawful gains could have made him as happy — it was proof that he would always turn up winners, even when faced off against the Border Patrol. During an attention getting airport goodbye, James lifted his face up from mine just long enough to say, “Promise me you’ll be back in Chicago soon.”

North Country Girl: Chapter 48 — The Accidental Model

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

James and I were on our way back to Mexico, driving his El Dorado from Chicago to Acapulco, probably the only time a Cadillac has been used as economy transport. After escaping from the police in Dallas, it was a relief to finally see the signs telling us the Mexican border was near — no more Texas! At the border crossing we were greeted with no more than the usual stares at the sight of a forty-three-year-old man and a twenty-one-year-old blonde in a new El Dorado covered in a layer of Texas dust; border patrol officials on both sides spent more time looking at us than at our passports.

As soon as we crossed the border, James, who had driven though most of Texas, pulled to the side of the road, slumped over, and mumbled that he had to get some sleep. We switched seats, I took over the wheel, and I drove into bedlam. Gone were the smooth, well-maintained US highways. I had to swerve into the other lane or the shoulder to avoid potholes that would have swallowed up the Caddy. There were also: long stretches of road that no one had gotten around to paving, men on horseback, kids leading burros, cows, pick up trucks carrying gigantic, loosely tethered cargo, buses with people riding on the top, flatbed trucks with 60-foot logs rattling away, more cows, dead dogs covered with frightening black clouds of vultures, and barefoot vendors with peeled oranges, bags of soft drinks, tamales, back scratchers, and loose cigarettes, all standing way too close to oncoming traffic, and sometimes even in the middle of the road. All of these nightmares were shrouded in a smog of exhaust and dust particles that hovered a constant three feet off the ground.

I had a death clutch on the steering wheel, but managed to pry my right hand loose, reach over, and switch off Linda Ronstadt. Music was too much of a distraction, and how many times had I heard “Blue Bayou” on this trip already? It was just as hard to tear my eyes from the hellish road; when it finally seemed safe, a quick glance showed me a James dead to the world, snoring slightly, mouth dangling open, looking quite a bit older than forty-three. My eyes and hands and mind fixed to the task at hand.

I drove for hours, deep into the Sonoran desert, where the traffic and the villages thinned out and I realized I had been clenching my jaw and my sphincter way too tight. The sun was setting to my right, a golden yolk dropping behind distant hills, setting the desert on fire. For a few minutes, everything was lit like a J.M. Turner painting, only a lot more arid. But here was night, drawing across the sky like a dark blue blanket, and then everything went black. I turned on the headlights and quickly switched to high beams, which flickered weakly through the still settling dust.

I noticed that the El Dorado seemed to be the only car going in either direction that had a working pair of headlights. Most drivers felt that the light of the moon was all the illumination they needed, while some cars had a single, dim headlight; I had to guess if it was the right or left one. It was like an awful game of chicken in some black and white teen movie. I crept along as far to the right of the road as possible, hoping no one was out for a stroll along the highway at seven at night, till I saw the flickering of a Vacantes motel sign. I didn’t care about cleanliness, price, nothing. I wanted out of the car.

After a night spent in an iron bedstead and a breakfast of tortillas and beans washed down with Nescafé, I said to James, “I am never driving in Mexico, day or night, again.” James teased me as a coward, and did the day’s drive, which was uncannily identical to the one the day before, with as much aplomb as if he had been toodling down Chicago’s Lakeside Drive. But that evening, when James got to experience the odd penchant Mexicans have for driving through the pitch dark countryside with their headlights off, he surprised me by pulling into a motel after only eleven hours behind the wheel.

By late afternoon of our third day in Mexico, we were winding up the mountains behind Acapulco, chasing the last rays of sun vanishing off in the west. We crested the top, and there, slipping in and out of sight as we made the hairpin turns downward, was Acapulco Bay, just visible as a silvery gleam separate from the velvet sky, where a thousand lights sparkled. James sighed, smiled, and reached over to take my hand. We were back.

It only took a few hours for James to find a place for us. Our home for the next few months was not oceanfront; it was even farther up the hill than the apartment I had shared with the three French Canadian girls. The building looked like a motel. Three blocky two-bedroom units shared a single umbrella table, four lounge chairs, and a shallow little pool that did have an eye-popping view of Acapulco. The other two units stood strangely empty the entire time we lived there. Our rent included daily maid service. A tiny, silent woman came in every morning, made us coffee, cleaned the apartment, took away our dirty laundry, and always asked if we would like lunch. James couldn’t or wouldn’t think ahead to meals, but once she left us a plate of chicken sandwiches that was one of the most delicious things I have ever eaten.

James and I fell back into last winter’s languid pleasure-seeking days, with only a few modifications. His budget did not allow for a season’s membership at a private beach club or for daily water-skiing. James shrugged off these deprivations without losing too much of his self-esteem. “Next year,” he told me.

When I had first met James he could go days without checking his portfolio, confident that his stock picking acumen meant that there was nowhere to go but up. Now every morning we drove down to the Sheraton’s newsstand, where James bought yesterday’s New York Times, lit a cigarette, and nervously tore through the papers to the stock market quotes.

James’s mood depended on that day-old news. If his stocks were down, he was furious with frustration: he had no way of contacting his broker other than waiting in line for hours at the sweltering office of the inept Mexican telephone company to make a long distance call. On those bad days I could look forward to hours of James taking on all comers at backgammon at the Villa Vera. He believed he could recoup some of his stock market losses by gambling, and he was desperate to prove to himself that he was a winner. He did win a lot, having the sharpie’s eye for novice players who were easily scalped, or blowhards who James taunted into making stupid moves and accepting hopeless doubles. His obsession left no time for meals. I spent those days at the Villa Vera swim-up bar, trying to fill up on bullshots (vodka and beef consommé), and wondering what our Mexican maid would have served for lunch.

The blessed days his stock posted a bit higher, the old preening, confident James reappeared. On one of those mornings James looked up from the business section with his vulpine grin and said, “Let’s have breakfast.” He took the paper and me to one of the Sheraton’s palm-shaded beachside tables, where I devoured a cheese omelet and everything in the bread basket, just in case. James was scribbling on the stock quotes and I was licking the last delicious buttery crumbs off my fingers, when a good-looking man, American by haircut, demeanor, and madras shorts, walked up to the table and introduced himself.

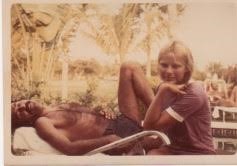

He was the director of a commercial promoting Mexican tourism and the model they were supposed to be filming that day hadn’t shown up. The director asked me, “Would you like to be in the commercial? I can pay you a hundred dollars. All you have to do is run back and forth on the beach for an hour.”

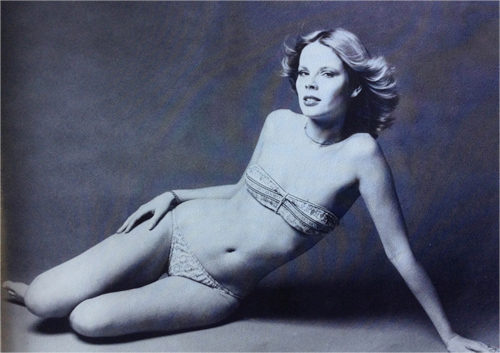

James piped up, “Yes, she’d love to!” while I felt a sharp pang of regret about the four buttered rolls I had just eaten. I was wearing nothing but my cute bronze bikini, a shade darker than my skin, held together in strategic places by golden rings.

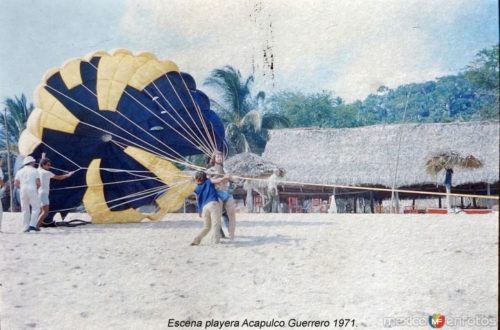

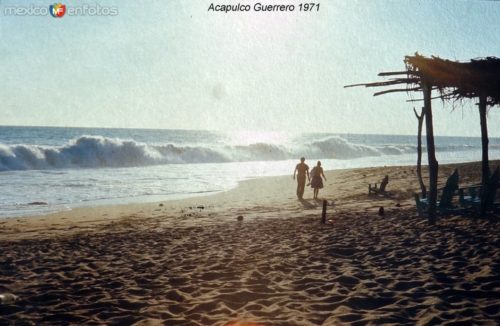

I followed the director down to where the waves frothed on the shore. It was the perfect Acapulco day, so gloriously sunny and balmy that it would inspire any snowbound Midwesterner to immediately start packing his bags.

The director pointed up and down the beach, in case I didn’t know where it was, said “Okay, start running,” and then yelled something at the cameraman. I ran, hopped, skipped, splashed, smiled, waved, and jumped around like an idiot, followed by the cameraman and the director, who kept yelling “Happier! Look happier!”

James stayed back at the Sheraton, stretched out on a lounge chair, admiring his handiwork each time I ran by. When it was over the director handed me a hundred dollar bill and promised to send me a copy of the commercial. At least I got the money. I saw the commercial once on TV, and only recognized it because my first thought was, “Hey, I have that same bikini.”

My sudden and accidental elevation into a professional model was a bigger boost to James’ ego then it was to mine. At the Villa Vera, he called me up from my swim-up bar stool to introduce me to yet another backgammon pigeon, saying, “This is my girlfriend, she’s a model.” James beamed as if he had sculpted me himself, a wolfish Pygmalion, and stroked my butt for good luck. Look, he was signaling his opponent, look at me, lucky and successful, a winner with a sexy young girlfriend. And now I’m going to beat the pants off you. Most of the time, he did. I was rewarded for my supporting role with thin gold chains for my wrist and neck, bijoux de plage, the sales lady said, simple and elegant. I still thought the uncut emeralds would look just fine on the beach.

For a few weeks, as his stocks kept ticking upwards, James gleefully slaughtered all comers at backgammon, and we were back in the Acapulco groove, as if no time or money had been lost, back to waterskiing in the morning, afternoons at Le Club (our entry into this private, posh oasis bought by James with a folded bill discretely palmed to the maitre d’), Carlos ’N Charlie’s for drinks and dinner if James was eating that evening, then always, always dancing at Armando’s.

It was the last good time.

One morning, James opened the New York Times to the stock pages and a black cloud covered his face and mood. This cloud did not blow away, but grew heavier and more ominous each day. There was nothing I could say, nothing I could do, except that hope tomorrow’s news would be better. It wasn’t, and neither was the next day’s. There was nothing James could do either, except watch his fortune evaporate. There was no more waterskiing, no more afternoons watching the peacocks strut around Le Club’s enormous pool. James got up in the morning, threw back his coffee, and headed straight for the Villa Vera. In their shadowy backgammon room James challenged his opponents to higher and higher stakes and became aggressively reckless with the doubling cue. It didn’t matter if he was winning or losing, I couldn’t bear to watch. I was grateful whenever James forgot to call for his lucky charm before facing a new opponent.

It didn’t seem possible, but meals became even more irregular. I looked in the mirror: I was model-skinny. James went from thin to cadaverous. Even though the sun shone every day, we carried our own bad weather with us. The fun, the glamour, were gone. We didn’t dance any more; James showed up nightly at Armando’s because that was what a happening guy in Acapulco did. He watched the happy couples on the dance floor and threw back vodka and sodas. I held my hands over my flip-flopping empty stomach and tried to figure out what would happen next.

It did not surprise me when James turned outlaw. There was always something felonious about him, a suspicion that there was a crime in his past or in his future.

Enough of winter had passed that it was safe for James to go back to Chicago without loss of face. He began planning our drive north, a plan that now included drug smuggling.

North Country Girl: Chapter 47 — “I Would Like to Purchase One Gun”

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

I moved to Chicago and into what I foolishly thought would be a soft, cushy life, an escape from serving cheeseburgers on paper plates, fretting about money, and living in run-down, under-heated student apartments. I imagined my days would be nothing but reading novels, my head resting on the warm chest of my handsome, wealthy lover, James, while he studied the stock reports. Our glittery, glamorous nights we would spend in Faces, the proto-Studio 54 of Chicago, or in the elegant backgammon club hidden away in the stately Ambassador West Hotel.

What I got was a job as a coat check girl and a half-crazed James watching the value of his stock portfolio circle the drain. I was sorry to see the money go too, and I cared about James, but his black Heathcliffian moods terrified me; he seemed to want to smash things or kill someone.

I love roller coasters, but the one my life with James had turned into was all in the dark: I couldn’t see when the thrilling ascents or stomach-dropping lows were coming. I couldn’t even tell if the ride was over and I needed get off. After only a few months of living with James, was it time to go?

Just when I had mentally packed my suitcases, there outside my coat check jail was James with a wolfish grin and glittering eyes and announcing “I’m hungry. Let’s go eat.” His stocks had rallied, and James was clawing his way back up to his rightful place in the universe.

The market and James’ mood continued to improve. Now he had to cope with his firm belief that only schmucks, putzes, and losers spent the winter in Chicago. Every night at the disco or backgammon club, another of James’s acquaintances came over to say goodbye, off to Miami, Montego Bay, Scottsdale. My backgammon partner held my hands in her bejeweled ones, gave me two quick air kisses, wished me luck, and took herself off to her winter home in Palm Beach.

Despite his reduced fortune, there was no way James was going to be seen in Chicago after January 1. He would rather have hidden in an underground bunker for three months. He had lost a lot of money, but his unsinkable belief in himself made even the slightest gain in his portfolio proof that he was a winner, a winner who was getting the hell out of Chicago.

We were going back to Mexico. But we were not going back to the expensive, gorgeous condo on the beach; James prided himself on being an old Acapulco hand.

“We’ll get a great deal on a place that hasn’t already been rented for the season. I know how to bargain them down.” And to save money on airplane tickets and jeep rental, James and I would drive the Cadillac from Chicago to Acapulco.

I decided not to cash out quite yet. I’d roll the dice with James once more. I happily quit my coat check job and packed up my bikinis and disco clothes in my pink Samsonite. James locked up the apartment, got the El Dorado out of the garage, and we drove off to Mexico.

The James I had moved in with five months ago always had a thick roll of hundred dollar bills on him. I don’t think I had ever heard him say the word bargain. This new cost-conscious James was going to take getting used to.

On the first day of driving, as the sun was setting over Missouri, I pointed out neon “Vacancy” signs. “We don’t need to spend money on a motel. I’m wide awake,” he assured me. We drove through the night, as we had the day, with James chain smoking and declaring that he wasn’t tired or hungry. As always, eating was something to put off as long as possible.

Despite the lack of regular meals and nights spent slumped in the bucket seat that was not quite comfortable enough for sleeping, I felt a glow of happiness growing with each mile that sped under the white walled tires. I was having another adventure, my own version of the movie where the dark and dangerous guy and his blonde girl are on the lam, the two of them against the world.

James was locked behind the leather-covered steering wheel: he couldn’t read catastrophic stock market reports, phone death threats to his broker, or have to face an unlucky run of the dice. The romance of the road relaxed him, too. He was looking forward to cheap and legal Quaaludes, deepening his tan under the Mexican sun, and fleecing suckers at backgammon. Cradled in the cocoon of the Caddy, we sped through the Midwest, chasing AM radio stations that weren’t country or church or squabbling about which of the six cassettes we should play for the hundredth time.

James drove and drove and drove. He was unsure about my driving — almost as unsure as I was. He could pack in a lot of hours behind the wheel, amped on nicotine and his own jumpy energy and his relief over ditching wintery Chicago. I was not eager to switch seats; I had never driven the Cadillac and only held a driver’s license by purest luck: I passed the road test in Colorado Springs by successfully making three right turns.

Finally, even James had to admit that he was human and pulled off the highway, red-eyed and jittery with lack of sleep. It was my turn to drive. I waited until the closest oncoming car was a mile away before pulling out on the Interstate. I glanced over at James, who was already out cold. Had he been awake, it would have been impossible for him not to take over as my driving instructor; James was as proud of his expertise in cars and driving as he was of everything he did. He could have found a lot to criticize in my overly cautious style of driving. But James was sawing logs, oblivious to my re-setting the cruise control to five miles under the speed limit.

As the day slipped by on the unvarying highway, a thin black strip across the brown and dreary plains, I began to feel more confident, since all I had to do was hold on to the wheel and point the car south. I steered that big wide boat of a car down that never-ending blacktop into Texas, feeling as safe as if I were inside an Abrams tank. But I did not have James’s stamina; after a few hours, I pulled into a motel parking lot and woke him up. I was almost in tears; I needed to sleep in a bed and use a bathroom that wasn’t in the back of a gas station.

Texas went on forever, as if it were its own country. We would wake, drive, and sleep, wake, eat a plate of eggs, drive, and sleep, and we’d still be in Texas.

We made one unexpected (by me) pit stop in Dallas. We cruised off the interstate and into a weirdly vacant downtown. I started pointing out hotel signs, thinking: a hot shower! A room service club sandwich eaten in bed in front of a TV! A toilet with that reassuring sanitary strip!

“We’re not staying here,” James side-eyed me. “I just have to pick something up.” What that something was became evident when we pulled up in front of a single story brick and glass store, bordered by alleys on both sides. Above the door was a single word: GUNS. The streaky windows had peeling paper signs announcing: “We buy used guns!” “Ask us about ammo!” and other disheartening phrases. Behind the windows, dusty headless mannequins in camo clothing held rifles in their chipped hands.

I was trying to figure out why all the blood was rushing down from my face and my stomach was clenching, and then my memory flashed on the pair of guns that had robbed and beaten my ex-boyfriend Steve and sent me plummeting naked off a second floor balcony.

James said, “Why do you look like that? It’s not for me. It’s for my doctor, the one who writes me prescriptions for Quaaludes. He said if I brought him a handgun, he’d give me all my scripts for free.” Apparently in Mexico, a much more sensible country, it was easier to buy drugs than guns.

I was spooked enough — unblinking, unthinking — to follow James into the gun shop. A bell rang as we pushed open the door, but I do not think any angels got their wings. The shop, like the street, was deserted. James and I wound our way through the racks and racks of big guns to the back, where a fat, slowly masticating man stood behind a glass display of smaller guns, hand-sized I guess.

Fat Texan took a good long look at the two of us, spit something into a cup, and said “Help ya?”

“Yes sir,” said James, “I would like to purchase a hand gun.” I wandered off to the front of the store, where there was a display of those camo hunting clothes and tried to find something in a size 5. I took one glance back to see James sighting down the barrel of what looked like a prop from Bonanza, my grandma Marie’s favorite TV show. He swung the gun around; the fat Texan had vanished.

I clinked the clothes hangers about and tried to articulate to myself first, so I could then convince James, why this was a Very Bad Idea. I looked out of the smudgy window and watched a black and white police car pull up behind the Cadillac. I didn’t know that I could feel any sicker. I tried to make myself very small and hid behind a rack of XXL neon orange vests.

The doorbell dinged again, the two cops entered the store and made a beeline for James, and I, a child of the sixties, cheesed it, the tinkling of the bell as I threw open the door announcing my getaway.

This is when I learned that it is always a bad idea to run from the police.

I ran without looking across the thankfully carless street, to an abandoned, unfinished office tower. It was fronted with thick cement columns; I ducked behind one that gave me a perfect sightline to the Cadillac, cop car, and gun store. What seemed like an hour passed. Then the cops came out, with James in the middle, thankfully not handcuffed. If they took James to jail and impounded the car, what was I going to do? Could it be illegal to buy a gun, I wondered?

Not in Texas. But transporting a minor across state lines for immoral purposes was. The fat gun store owner had called the cops. He had taken one look at James’s swarthy Greek complexion and realized here was a nefarious foreigner bent on despoiling a flower of American girlhood. James carried an outlaw air, and the two-decade difference in our ages made me look younger than 21. Fat Texan told the cops that I had escaped the evil grasp of my white slaver, who was buying a gun to control me.

I watched from my hiding spot. James lit a cigarette and handed over the car keys to the cops as nonchalantly as if he were handing them to a valet. He leaned against the Caddy and a cop popped the trunk, took out my pink Samsonite, rummaged through it, and held up a pair of white lace panties, evidence that there had been an innocent young girl in the car.

The cops searched James’ luggage and then the rest of the car. “I wasn’t worried,” James told me later. “I knew there was nothing in the car. The problem was you.”

It seemed another hour went by, or at least five or six cigarettes worth of time. Somehow James knew that I had not kept running out to the highway to hitch a ride back north. He threw a cigarette butt down, stomped heavily on it, and hollered, “Gay! Gay! Get yer ass over here!” almost to the admiration of the two cops. He repeated it a couple of times before I was convinced that I had no alternative but to come out.

“Ma’am,” said one of the cops, and I turned around thinking he was talking to someone who had suddenly appeared behind me. “Ma’am! Yes you. Are you okay, ma’am?” I nodded, unable to separate my tongue from the roof of my mouth. “And this is you, right?” He held my driver’s license in one hand, my purse in his other. Again I nodded.

“See sir, she’s free, white, and twenty-one, sir!” cackled James and put his arm around me. I managed to find a weak smile for the two cops, who were obviously disappointed. James shook their hands and apologized for wasting their time. We waited outside the car till they drove away, and then I flopped into the bucket seat, leaving sweat marks on the white leather. James lit another cigarette, started the engine and we pulled gunless out of Big D and headed back south.

North Country Girl: Chapter 46 — Locked in the Coat Check

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

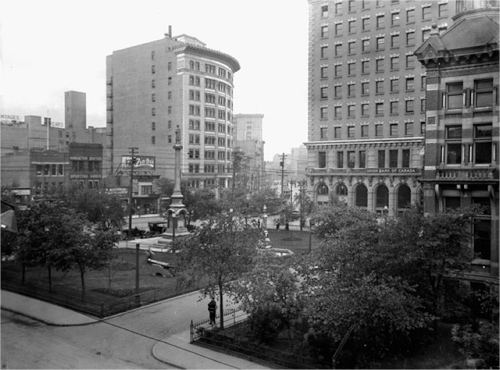

I moved to Chicago and into the kind of big-city sophisticated life I had invented as a child growing up in Duluth to explain why my Barbie doll needed such extensive wardrobe changes, a life that somehow had miraculously found me. My new home was a 57-story skyscraper in the heart of the Near North party zone; from my tenth floor apartment window I looked down on Newberry Plaza’s sparkling outdoor pool and marveled at how lucky I was.

James, my suave, much older lover, assured me that I did not have to work, but I had grown too accustomed to having a thick roll of dollar bills squirreled away. While I was happy to have James pick up the rent and the bar and restaurant tabs, it seemed weird to ask him for money to buy contact lens solution or Tampax.

I put on make up and a cute dress and took the elevator down to apply for a job at Arnie’s Steakhouse, a new restaurant on the ground floor of our building. I was interviewed by Arnie Morton himself for all of two minutes while he smoked a huge cigar and stared at my unimpressive chest. I was hired, but unfortunately Arnie thought a classy joint like his should have male waiters. I couldn’t even cocktail waitress, as the bar area was literally one huge shiny black bar, overseen by gruff, older bartenders in bowties and black vests.

Arnie pointed his cigar at my breasts and said “Coat check” and I found myself nodding. I remembered trudging through the snow to my waitress job at Pracna and thought how nice it would be to commute to work via elevator.

It was a horrible job. I sat on my ass in the tiny coat check room for hours, with absolutely nothing to do. The second day I brought a book, but the manager reached into my little nook, tapped me on the shoulder, and shook his head.

Eventually, as the weather cooled, the coat room filled and emptied several times a night. It was good that my expenses were so minor as the tip jar overflowing with one dollar bills did belong to me but was collected by the manager at the end of my shift. I was a sharecropper; I only got to keep a tip if the customer put the dollar bill directly in my hand. (To this day, even though not a single person I know who’s worked coat check has ever heard of such a policy, I always hand the coat check girl my buck.) I should have quit, but instead, wallowing in a stew of resentment and self-justification, I began dipping into the tip jar when no one was looking, and I amused myself by trying on the furs that were left in my care and pawing through coat pockets.

When I wasn’t at work, James and I were together almost constantly. He didn’t have a real job the way the men I knew had jobs. Today James would be a day-trader; in that pre-computer age he had to rely on the newspaper and the one TV station that had a rudimentary stock market ticker running on the bottom of the screen. James called his broker several times a day, buying and selling or just trading tips and market gossip.

I did not so much as make coffee in that brand new kitchen; I don’t think I even ran the dishwasher once. James and I had our coffee and an occasional omelet while reading the Chicago Sun-Times, the Tribune, and the previous day’s New York Times in a booth at the Oak Street Diner. James focused on the business sections, patiently decoding the stock market quotes for me. Unfortunately, this was one part of my Jamesian education that didn’t stick. Then it was back to the apartment so James could watch the ticker and call his broker. Saturdays and Sundays, when the market was closed, we went out for bloody marys and eggs benedict and the Times crossword. I resented having to share the puzzle, but I always let James fill in the easier squares, which he did with a self-congratulatory “Aha!” before finishing the job myself.

On my nights off from Arnie’s, James took me out to eat, favoring restaurants in Greektown, a short cab ride north. It turned out that Rogers was taken from some longer Greek name, and even though he couldn’t speak a word of the language, James acted as if every chef and waiter in Greektown were a long lost cousin. I took me a while to get over my dislike of the piney-tasting Retsina James insisted on ordering, but I couldn’t get enough of the saganaki, melty cheese dramatically set on fire at our table by an always mustachioed Greek waiter. James never took me back to the Pump Room, though I made a point of looking longingly inside every time we passed.