Jamie Wyeth: Born to Paint

After the September 11 attacks, Jamie Wyeth was driving along the country roads — some as bumpy as washboards — in Pennsylvania’s pastoral Brandywine Valley when he saw a white barn with a huge American flag painted on it. The barn sat on top of a hill; a pond at the bottom of the hill reflected the stars and stripes. He immediately decided to paint it. He called this painting Patriot’s Barn.

“I had to record this stunning image,” he says. He goes on to call himself a diarist or recorder of everyday events and people. “I hate the idea of ‘now I’m creating a painting for an audience.’ My painting is simply recording my life and my thoughts, as if I were doing a diary.”

But if you look at the breadth of his work — from sketches to miniature mixed-media dioramas to children’s book illustrations to monumental landscapes to life-sized portraits — Jamie is much more than just a recorder. He is an expert painter of imposing realist paintings whose goal is to describe something authentic and American. “Whether I’m painting a person or a seagull or a pig, I like to think that if that pig painted, he’d paint himself exactly the way I was doing it. That’s what thrills me,” he says.

Jamie Wyeth

Jamie Wyeth was born in 1946 with a silver paintbrush in his mouth as the third-generation champion for America’s first family of art — a family famous for distinctive and imaginative realism. Wyeth’s grandfather, Newell Convers Wyeth, better known as N.C. Wyeth, was an important illustrator whose swarthy, swashbuckling pirates, noble pilgrims, cowboys, and Indians embellished many children’s books — Treasure Island, The Last of the Mohicans, and The Yearling, to name a few. His very first sale (a cowboy riding a bronco) was for the cover of the February 21, 1903, issue of The Saturday Evening Post. N.C. was born in 1882 and died tragically in 1945 when his car stalled on the railroad tracks in the path of an oncoming freight train — just a few miles from his home near the village of Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania.

Jamie’s father, Andrew (1917–2009), was world famous for painting stark, melancholy scenes depicting the hardscrabble life of farmers in rural Pennsylvania and fishermen in coastal Maine — people and places that seem worn down by time, the tides, and life’s worries. He worked in egg tempera — a medium dating back to the Middle Ages but not much in favor with 20th-century artists — to create his matte, mostly monochromatic, and often brooding images. He captured the same desolation seen in the lonely landscapes, Depression-era cityscapes, and isolated figures of painter Edward Hopper and that photographers Dorthea Lange, Diane Arbus, and Walker Evans captured on film.

Jamie Wyeth

Andrew’s loyalty to realism when every other artist in the world was going abstract marks him as both an iconoclast and a rebel in his time. Art critic Ray Mark Rinaldi notes, “No American painter was more skilled than [Andrew] Wyeth or possessed a greater ability to make marks with his artist’s tools, or with tempera paint, or pencil, or — and this is the revelation to most folks — watercolor.”

Jamie learned the family trade from his father and the basics of drawing from his aunt, Carolyn Wyeth (1909–1994), who, like her brother, learned painting at N.C.’s knee. “My grandfather’s studio was physically just up the hill from our house. It was left just as he left it,” Jamie says. “It was full of costumes and guns and all the other trappings of illustration. I would spend days upon days up there.”

“Both trained as if they were apprentices, Andrew to his father, N.C. Wyeth, and Jamie to both his father and his aunt Carolyn,” says Timothy Standring, Gates Foundation Curator of Painting and Sculpture at the Denver Art Museum and curator of Wyeth: Andrew and Jamie in the Studio. While organizing this exhibition, Standring was given unprecedented access to the Wyeth archives and papers and could freely rummage through all the drawers of Jamie’s studios in Maine and Delaware, sometimes finding early sketches that Jamie had completely forgotten.

Jamie Wyeth started drawing when he was three and became a working artist when still quite young. “I had gone to public school like every other kid my age, but I was not interested in basketball or football. … I only wanted to paint,” he recalls. “My father was taken out of school because of illness when he was young. I thought that was a great pattern and determined that I was going to do the same thing,” he adds. His family agreed to let him leave school after the sixth grade, and that’s when he “seriously started painting.”

His father, Andrew, gave Jamie half the studio to work in. Jamie recalls that Andrew was a feverish worker who loved to play classical music loudly while he worked. Jamie preferred — and still does — working alone and in silence. “The only problem is that the record player was in my part of the studio, so I’d stuff my ears with wax.” Father and son painted together on many occasions, even modeling for each other. But were they pals or rivals? Jamie says that it was always a little bit of both.

Although their studio practices were different, they were similar in many ways. “Both used media in a highly unorthodox manner,” Standring says, noting that, even early in his career, Andrew blotted and smeared washes or scored through washes of ink with wire brushes or even his fingernails to get the desired effect. Similarly, Jamie often paints in mixed media — sometimes using watercolor, wash, and oil in a single painting. “I put paint in my mouth, on my fingers, on toothpicks, and often paint with the wrong end of the brush,” Jamie says. “I’m a terrible technician.” There was a period of time when he put his paintings into the oven because he wanted them to dry quickly, and when he wanted his paintings to dry slowly, he put oil of clove into the paint. “They smelled great,” he says, “but I think that Portrait of Lady took about a decade to dry completely.”

After a brief fling with egg tempera, Jamie chose to work mainly in oils, allowing him a broader and brighter palette than his father’s and bringing him into a direct line with his grandfather N.C. Wyeth, whose love of color and texture was legendary.

“But … like his father, he [Jamie] doesn’t want to paint under any fixed method or system, and instead treats each work individually as its images demand, which helps explain his obsessive search for new and interesting materials to experiment with,” Standring notes. “By allowing himself full rein with a multitude of media applied any which way, Jamie ultimately began to distinguish himself from Andrew.”

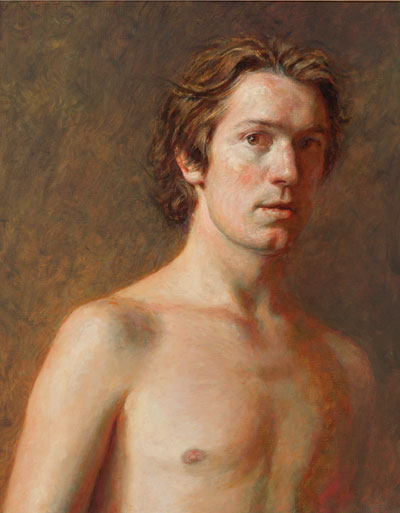

When he was just 17, Jamie painted Portrait of Shorty, an oil depicting a haggard, unshaven Chadds Ford neighbor wearing a dirty undershirt but sitting in what looks like a damask-covered antique wing chair. Jamie’s very first commission, the Portrait of Helen Taussig, was painted the same year. It was a commission from Johns Hopkins University, which wanted to honor Dr. Helen Brooke Taussig, a pioneer in pediatric cardiology. They could not afford Andrew Wyeth’s fee, but agreed when he recommended his son. Jamie recalls a gasp of horror from the assembled crowd when the flinty, intense portrait was unveiled. In fact, Johns Hopkins did not hang the portrait but gave it to Dr. Taussig, who wrapped it in a big towel and stuck it in her attic. “It is not a Betty Crocker portrait,” Jamie acknowledges.

Jamie Wyeth

Jamie Wyeth

Jamie Wyeth

But still, not an auspicious beginning to Jamie’s career, and in fact, he was quite devastated at the time and has done very few commissioned portraits since. It was a pleasant surprise when Johns Hopkins reached out to him recently to say that, after all these years, they were going to display the original portrait. But the mixed reaction to his portrayal of Helen Taussig was certainly a harbinger of the later reaction to portraits he did of Andy Warhol, which set off a tsunami of both praise and criticism in the art world.

“I work every day all day,” Jamie says. “I’m kind of a boring person because that’s all I do and that’s all I want to do. I don’t have any hobbies.” He goes on to say that painting does not require editors, sound people, lighting engineers, or an orchestra. “All you need is a stick with some hair on the end of it and sticky stuff called paint and a piece of cloth.” Jamie, by the way, paints with his father’s old paintbrushes because “they already made a lot of great paintings, so they know what to do,” he says with a smile.

“Although Jamie’s settings may look like the Brandywine Valley or Midcoast Maine of his father’s works, they are more a scenic backdrop for his quirky sensibility, which seeks out overlooked or peculiar objects, such as docking posts, plow blades, buzz saws, storage tanks, or sewer pipes,” Standring says. “One can look at his compositions as if they were repurposed accidental photographs; unintended compositions fraught with meaning,”

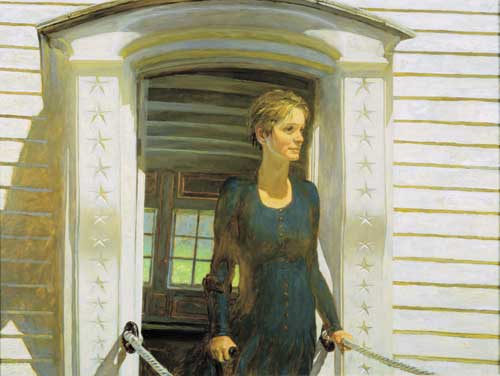

The subjects of Jamie Wyeth’s Pennsylvania paintings are agrarian — chickens, pigs, goats, horses, dogs, and barns — but freer and more humorous than those of his father. He also paints his wife Phyllis — a DuPont descendent and champion equestrian before she was disabled in an auto accident when she was in her 20s — standing in a doorway (Southern Light, opposite page) or capably at the reins of a carriage pulled by her Connemara ponies (And Then into the Deep Gorge and Connemara Four). In Maine, he paints lobster traps, circling gulls, white clapboard churches, weathered gray-shingled houses, and the lighthouse in which he lives (Tenants Harbor Light, aka Southern Island Light). “The sea has always attracted me,” he says, “and what’s more emblematic of the sea than to live in a lighthouse? It could be very cliché-ridden, but who cares … it is my home.

“My life is solitary. I’m alone on this island out at sea in Maine, but I don’t find it lonely,” Jamie says. “Here I am a mile offshore. I have to row back and forth, and that gives me focus in my work.”

He enjoys the solitary life when working. Sometimes, when painting outdoors on Monhegan Island, he sets up his easel inside an old, rank-smelling plywood fish-bait box (about the size of a refrigerator, with one side missing) to hide from tourists. “It is distracting when people talk to me while I’m painting,” he says. “When I’m inside the box, they can see that I don’t want to talk and, eventually, they go away.”

But when not painting, he’s quite welcoming to visitors, entertaining them with the stories behind his works. And every painting has one. For example, he painted Winter Pig (opposite page) in the dead of winter. In the midst of the project, he was called away. “When I returned, I discovered my model had eaten most of my pigments — some of which were very toxic,” he says. “For the next week, the farmer and I noticed that the pig was producing the most amazing rainbow-colored poop.” The 600-pounder survived the incident and stayed on as Jamie’s pet.

Jamie is always asked about Kleberg, the yellow lab with the black circle around his eye. “There’s a simple story,” he says. One day when Kleberg got too close to his easel, Jamie dipped his brush into black paint and put a circle around the dog’s eye. A few days later, a deliveryman remarked on the amazing marking on the dog — so did everyone who saw the dog. “Kleberg looked at me and I looked at him and we decided that the marking was here to stay,” he says. Eventually, he used mustache dye instead of black paint because the dye would last around a month. The dog seemed to enjoy the notoriety his marking gave him: “He would come to me when it needed to be redone,” Jamie says with a smile.

Jamie Wyeth

Jamie Wyeth

Jamie Wyeth

Although he demurs when you ask him about it, there is no doubt that Jamie Wyeth is the modern standard-bearer for the Brandywine School of art, founded by one of America’s foremost illustrators, Howard Pyle (1853–1911), who illustrated books by such luminaries as Mark Twain and Robert Louis Stevenson.

Pyle’s influence was rooted in his dissatisfaction with the confines of formal art education. His art school, set on the scenic banks of the Brandywine River, attracted such star pupils as Jamie’s grandfather N.C. Wyeth, Harvey Dunn, W.H.D. Koerner, Frank Schoonover, Jessie Willcox Smith, and Elizabeth Shippen Green. Pyle’s teaching was unique in that he rarely taught his students technique. Nor did he dictate what kind of paint or brushes to use. Instead, he taught what he referred to as “the pictorial idea” that an illustration should capture a powerful moment in time, a moment the viewer could comprehend in a single glance.

Pyle said that an illustration should make an impact and tell a dramatic story from a distance of 10 feet. He famously told his students: “Don’t make it necessary to ask questions about your picture. It’s utterly impossible for you to go to all the newsstands and explain your pictures.”

What became known as the Brandywine School of Illustration would influence many others at the turn of the 20th century and beyond, including Maxfield Parrish and Norman Rockwell. Howard Pyle’s school was also famous for admitting women in equal numbers to men. Many of his students, including Sarah Stilwell-Weber and Kathleen Richardson Wireman, went on to illustrate covers for The Saturday Evening Post and numerous other magazines.

By the middle of the 20th century, realism (but, interestingly, not the Wyeths) fell out of favor, and illustration became a pejorative term in the art critic’s vocabulary. Abstract expressionism, minimalism, existentialism, pop art, and op art ruled the art world. “For years, you didn’t see art history or studio art students in the museum looking at illustration,” says James Duff, director emeritus of the Brandywine River Museum of Art. “About a dozen years ago, I became aware that professors were bringing their classes specifically to look at illustration … to look at Howard Pyle.” So, according to Duff, realism and illustration have come full circle. “If you live long enough, everything comes around again,” he says. Indeed, contemporary scholars and art critics are seeing Pyle’s influence in many spheres, from cartoonists Walt Disney and Charles Schulz to the current group of graphic-novel illustrators and beyond.

Jamie, too, has noticed that more and more young people are getting into making art and illustration, and he calls it an exciting profession. “I encourage art,” he says, “because you can work anywhere and with anything. Sometimes terrible messes come out of making art” — he admits to destroying half of what he creates — “but that’s okay, too.”

What is the Wyeth family’s place in the firmament of art today? Thomas Padon, director of the Brandywine River Museum of Art, summarizes: “Just as there’s a remarkable continuity in the three generations of Wyeth family artists in the sense of their shared creativity and abiding sense of place, there are interesting differences that set them apart in distinct ways. Taken together, their body of work is one of the major achievements in American art.”

Duff concurs: “N.C. Wyeth, Andrew Wyeth, and Jamie Wyeth are being increasingly recognized for their unique contributions to American art, and their importance will continue to grow through the decades with recognition of their amazing technical abilities, their perspectives on the human condition, and the sheer beauty of their accomplishments.”

Read our 2011 story about Jamie and his father and grandfather, “Wyeth Family Genius.”