Unwanted: A Teenage Memoir of Japanese Internment

I am a member of a once despised minority group, American Japanese, who spent three-and-a-half years incarcerated in an American concentration camp during World War II. Although that ordeal ended 72 years ago, the impact of that experience on my life and its broader implications for American society resonate deeply to this day.

At the beginning of the war, roughly 10 percent of the adult “alien” men on the West Coast (Japan-born persons being ineligible for citizenship) were picked up by the FBI as potentially dangerous and interned by the Justice Department, effectively robbing the community of leadership. We had been under surveillance for quite a while, and these men were singled out. My father, who was an alien, was not picked up, though many of our friends were. None ever were convicted of a crime or act of sabotage, though many were held for years in captivity.

I was a U.S. citizen by birth, but the distinction meant nothing at the time. My entire family — my parents, two sisters, and I — was sent to Poston in southwestern Arizona, geographically the largest of the 10 War Relocation Authority (WRA) camps where American Japanese were held. At the time, I had just turned 12. By the time we were permitted to leave, I was 15.

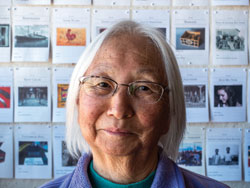

Photo by Dave Izu

We, along with approximately 120,000 others, spent the better part of four years in desolate areas where we were monitored, our movements restricted. We ate in mess halls, and our tar-paper barracks were so flimsy I remember wind and dust storms so strong that rooftops were torn off, debris flying around like crumpled paper.

Perhaps even more of a shock to me than the prison-like conditions was the fact that for the first time in my life, I was living totally surrounded by others of Japanese descent. In my early school years, most of my classmates were white, with a scattering of Mexican-American kids. Although I was one of the few American Japanese in my small town, I never experienced any prejudice there. But at Poston, my farm upbringing contrasted sharply with the sophistication, manners, and clothes of the American-Japanese kids from Los Angeles and other cities.

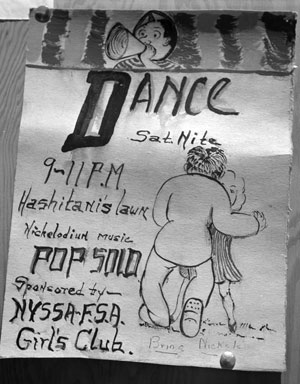

Here we were, all locked up together, doing our best to be “normal” teens. My mother disapproved of the camp’s faster growing-up process, driven by the city kids. She wasn’t sure about my going to the parties and dances that were a big part of teen life at the camp, and she did not want me to have a brassiere or wear makeup. I missed my white classmates, my home, my town, and my less-pressured life. I felt like an ugly duckling.

We had the trappings of society like schools, jobs, a camp government, a police and fire department. My father did some woodcarving while my mother took sewing lessons, making our dresses. I spent a lot of time reading books from the library. But life was far from normal. The usual social hierarchy was turned upside down, with the elders stripped of power and the young freer to pursue their interests.

It was the pettiness of life in camp that got to me. Almost every aspect of everyone’s life was known to all, and this promoted a culture of gossip and rumor mongering, with whispers and speculations about others filling our time. The meanness, the nastiness exhibited, the way we picked on one another, was an ugliness I hadn’t known before. Of course, it was a manifestation of the cramped living conditions, the forced idleness, and the insecurity of our situation.

A group formerly known for hard work and pride in our accomplishments was reduced to committing little acts of rebellion aimed generally at the government and administration who were oppressing us. People “stole” wood scraps to make furniture and pilfered food from the mess halls. Many did not feel that manual work was worth doing and slacked off, held strikes, and quit their “jobs.” My father “borrowed” a tractor and took a mob of kids to the Colorado River, a couple of miles from the camp.

Photo from The National Archives and records Administration

I was too young and naive to understand the bigger picture, but the smaller world I inhabited was beset with contradictions. In eighth grade, a white schoolteacher from Massachusetts ordered us to memorize a Marc Antony speech from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. “Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears,” it began. “I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him. The evil that men do lives after them; The good is oft interred with their bones.” We labored mightily to master those lines and dozens more. But, alas, most of us had trouble doing it, and she castigated us as ignorant, lazy know-nothings.

There were those, particularly older men, who listened to Japanese propaganda broadcasts on smuggled-in radios. Reports of Japanese victories would elicit some cheers. Clumps of men would discuss the latest “news,” sneering at those who didn’t believe, severely criticizing those who remained loyal to the U.S.

Our community was caught up in this international war at a particularly sensitive period. My parents’ generation was still culturally old country. Some, like my mother, never learned to speak English. Their children, including me, were rapidly becoming Americanized. I joined the Girl Scouts and edited the junior high newspaper, The Desert Daze.

In prewar times, it was customary to send children to Japanese school because many believed that eventually they were going to return to their home country. In some places, it was a Saturday-only class, but in my case, we attended an hour of Japanese lessons each day, after American school, and our teachers were brought from Japan. I perfected my calligraphy and reading and writing, but the authoritarian style and emphasis on obedience went against what we were learning in the American school. Even though most of us spoke Japanese at home with our parents, we weren’t interested in it. English was becoming our main language.

These intergenerational conflicts, typical of the American immigrant experience, intensified in the camp. In the beginning, because no Issei (immigrant generation) were allowed any leadership roles in the camps, the block managers and elected members of the camp councils were all young people who had been born on American soil. This powerlessness of the older men was manifest in continuous grumbling about how callow and ill-prepared for leadership the young were.

A call by the Japanese American Citizens League (composed of young men and women who acted as the liaison between the people and the government) to allow young men to serve in the American military to prove their loyalty provoked intense conflict. I had no brothers, but I know that my parents thought that to send our youth to fight for this country, the very country that had imprisoned us, was absolutely unacceptable. I had cousins who “resisted,” refusing to comply with draft orders, and I also had an uncle who served as an officer in the Army, fighting in Europe.

Russell Lee/Library of Congress

These divisions in the camp were reflected in my family. Several years into our incarceration, my father decided that he would apply for repatriation. He had had enough of the mistreatment, feeling that prospects would be better in Japan, where the family had some property. I was astounded and angry. America was my home, and I knew that I was not Japanese. I had no interest in going to Japan. I’d seen enough of the patriarchal, authoritarian style of Japanese society in my own family and others to know that I didn’t want to be a Japanese woman, subservient and under the control of men.

I fought with my parents, even writing letters to magazine editors, but nothing I did would change their minds. As the war wound down I watched as friends left, moving to eastern parts of the U.S. and then back to the West Coast. I was feeling trapped. But when Japan was defeated, my father learned that there was nothing to go back to. He changed his mind and we resettled in Oceanside.

For the rest of my father’s life, we never talked about the camp experience in a serious way. It was too painful. He started farming again but wasn’t very successful. Two years later my mother died of bleeding ulcers. My father became more passive and quiet.

For my part, I was relieved that the ordeal was over and determined to put it out of my mind. I went to college, married a white man, raised a family, lived mostly in white society. I protested the Vietnam War and was active in the civil rights movement. And in the course of these activities, I began to think about my own background.

The wars against Korea and Vietnam made me very aware of American attitudes toward Asians, and the topic of camp came up from time to time. I ran into a therapist at a party who questioned me about my experience, and I brushed it off as not very important. But she pressed on, telling me how formative those early adolescent years were, that I should reexamine those times. This stuck with me, and when a movement for redress began to take shape, I joined in and worked at the legislative level and as a named plaintiff in a court case that went to the Supreme Court.

I learned that the most damaging event that occurred in the camps was a so-called “loyalty questionnaire” administered in 1943, mandatory for everyone 17 and older. It was used to separate the “loyal” from the “disloyal.” It was a poorly designed instrument, resulting in divided families, friends. On the question of agreeing to serve in the American military, to say no was to automatically designate “disloyalty.” My cousins said no and were charged with being draft dodgers. A sympathetic judge fined them one penny.

After the government turned the camp at Tule Lake into a segregation center for all “disloyals” and troublemakers, I watched friends loaded onto trucks to be taken there. By the flimsy logic of the day, our family should have been sent there as well — I never learned why we were not. Perhaps a fortunate oversight kept us out.

The government seemed hell-bent on tarnishing all of us as aliens — and enemy aliens at that. How could we remain “loyal” to a country that had held us captive for years, impoverishing us in so many ways? How were we to

respond to these humiliations and victimization? We were expected to disallow our Japanese heritage and submit to the demands of our captors. And we did. But it left us with a badly damaged community, an ever-present split between the “loyals” and “disloyals,” and a deep understanding about how vulnerable we were.

Ironically, we were very good at adapting and melting into the American middle class, earning the label of “model minority.” In my own case, I lost my primal language, distanced myself from the American-Japanese community, and for many years didn’t look back. We paid a heavy emotional price, and the issue of identity has always dogged us: Can we truly be American?

It’s been a long time since World War II, and one would think that Poston would be a fading memory, but it is not. I have made pilgrimages to Tule Lake, seeking a better understanding of our history. Though I have spent my years in white society and my children are half white, I am certain that given particular circumstances, I could be targeted again for my political views, ethnic background, for my religion or being a member of a group identified as other.

I am not bitter, but I remain quite angry. I am a liberal, a believer in equality, but I am also a cynic. I don’t think that our Founding Fathers really meant to extend equality to everybody, but the words and sentiments remain part of our Constitution. The struggle for our ideals continues, and it is necessary to remind us about what happened to me and 120,000 other Americans, because without that memory, it could easily happen again.

Chizu Omori is a freelance journalist and co-producer of the documentary Rabbit in the Moon with her sister Emiko Omori, chronicling the experiences of Japanese Americans in WWII internment camps. This essay is part of What It Means to Be American, a partnership of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and Zócalo Public Square.

This article is featured in the May/June 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Originally published at Zócalo Public Square (zocalopublicsquare.org).