Peggy Lee’s Pursuit of Positivity

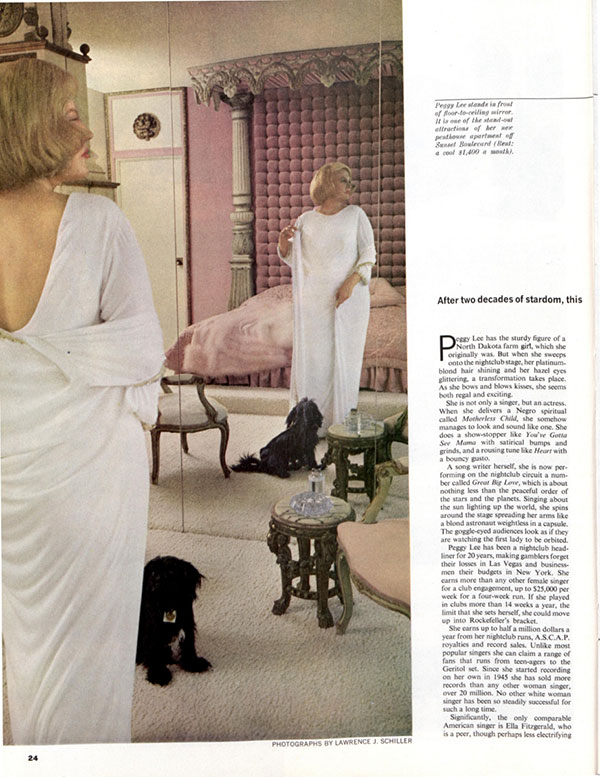

Writing about the irrepressible Peggy Lee in this magazine in 1964, Thomas C. Wheeler described one of the jazz singer’s recent performances of her song “Great Big Love”: “Singing about the sun lighting up the world, she spins around the stage spreading her arms like a blonde astronaut weightless in a capsule. The goggle-eyed audiences look as if they are watching the first lady to be orbited.”

At the time, Lee’s career was unprecedented. She had sold more than 20 million records in her two decades of recording music, and she attracted a large fanbase that was diverse in every possible way. Today, she would be 100 years old.

In spite of her hard work and good fortune, Peggy Lee was often plagued with profound unhappiness that sent her on a spiritual quest for inner peace.

After being discovered by Benny Goodman in the ’40s, “Miss Peggy Lee” sold her sultry jazz persona with hits like “Somebody Else Is Taking My Place,” “Why Don’t You Do Right?,” and “Fever.” She cut records at breakneck speed, arranging jazz standards and pop songs along with her own work. She starred in The Lady and the Tramp, a remake of The Jazz Singer, and Pete Kelly’s Blues, earning an Oscar nomination.

Although Lee’s music career had been a remarkable success — affording her a peach-interior mansion in Bel Air — the sensual singer struggled with a traumatic childhood and rocky relationships. In 1969, she released the song that would come to embody her career, the one in which she asked “Is That All There Is?”

The song tells about a young girl who sees “the whole world go up in flames” when her house catches fire, an experience Lee had been through herself. She had also lost her mother at a young age. When Peggy Lee went searching for answers to her life’s tragic questions, she went to Ernest Holmes and The Science of Mind.

Holmes was a leader in the metaphysical Religious Science movement. He encouraged its adherents to use positive intentions in order to conjure happiness. Holmes’s 1926 book, The Science of Mind, was a hit with other Hollywood luminaries too, like Cecil B. DeMille and Cary Grant. Lee became close with Holmes, consulting him often and even coming to affectionately call him “Papa,” according to James Gavin’s biography Is That All There Is? The Strange Life of Peggy Lee.

As Holmes wrote in the credo of his church, “We believe in the direct revelation of truth through our intuitive and spiritual nature, and that anyone may become a revealer of truth who lives in close contact with the indwelling God.” Gavin explains the appeal of Holmes’s hybrid religion: “For Lee, who already lived by the force of her imagination, Holmes’s edicts seemed heaven-sent, the confirmation of all she wished to believe.” She had been “looking for God” since her mother died when she was four years old.

Peggy Lee singing “Is That All There Is?” in 1969. (Uploaded to YouTube by Peggy Lee / Universal Music Group)

Gavin’s biography paints a less-than-charitable picture of Peggy Lee, exposing her as a woman who was, “by all accounts, an alcoholic, a prescription-drug addict, a heavy smoker and a binge eater frequently out of touch with reality.” But no one could ever say she didn’t put in the work, or that she didn’t at least try to improve herself. In her conversation with Wheeler for the Post in 1964, Lee described her approach to spirituality and self-improvement, specifically recalling an evening with composer Cy Coleman in New York in which she guided him through a calming meditation, repeating the phrase “receiving and giving” to him over and over. “That’s what we have to do, all the time. Receiving and giving,” she said.

Her anthem “Is That All There Is?” might seem — on its face — to be a lamentation to “break out the booze and have a ball” in light of life’s disappointments, but she didn’t wish for it to be interpreted that way (at least, according to an interview she gave with Science of Mind magazine in 1987). Lee said that the title and chorus had a different meaning for her. She had moved the emphasis of the chorus from that to is to try to make the song into a hopeful affirmation: “To me, it was just the opposite. It said we go through one experience after another, some of them negative into a positive. We learn, grow stronger, can go on to new experiences because there is always more.”

Featured Image: Peggy Lee (Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain)

Amazing “Grace”: Jeff Buckley’s Timeless Album Turns 25

It’s easy to play the “What If?” game in popular music. “What if John Lennon hadn’t died? “What if N.W.A. hadn’t broken up?” “What if MTV hadn’t happened in 1981?” “What if disco kept going?” Since 1997, music fans have asked “What If?” about Jeff Buckley. After a promising start, the young musician died in a tragic accident at the age of 30. He left behind one complete full-length album, Grace, that has only gained more acclaim in the years since his passing. This week marks the 25th anniversary of Grace and an all-too-brief glimpse of a talent that had more to offer.

Jeffrey Scott Buckley grew up in the shadow of music. His father, Tim Buckley, was a noted folk and jazz musician; the younger Buckley, raised as Scottie Moorhead by his mother and stepfather, met his biological father a single time when he was eight. By the next year, Tim Buckley was dead of an overdose. After his biological father’s death, Moorhead decided to go by his birth name. Buckley’s mother had raised him in music, as she herself was a classically trained cellist and pianist. He picked up the guitar at age five and learned to sing for his family. His stepfather introduced him to ’60s and ’70s rock, while Buckley gravitated to progressive rock and jazz on his own.

“Last Goodbye” by Jeff Buckley (Jeff Buckley / VEVO)

After high school and a year at the Musicians Institute in California, Buckley plied his trade across bands, backing gigs, and studio work, but never as lead singer. At age 23, he moved to New York for several months, expanding his palette of influences to punk and Robert Johnson-style blues. When his late father’s former manager, Herb Cohen, said he’d help the young artist get a demo together, Buckley returned to L.A. The result, Babylon Dungeon Sessions, contained four songs, including “Unforgiven” (which would morph over time into “Last Goodbye”). In 1991, Buckley made his solo debut at a tribute show for his father.

Buckley played for a bit with the band Gods and Monsters before striking out on his own, carving out regular gigs in NYC. He slowly built a fanbase that generated attention from record labels. Buckley eventually signed with Columbia Records in 1992. Live at Sin-é, a four song EP, was recorded and released in 1993. That same year, he put together a band to begin work on the project that would become Grace.

Legendary engineer and producer Andy Wallace, who had worked with everyone from Prince and Springsteen to Nirvana and Slayer, co-produced the album with Buckley. Grace ended up being a 10-song affair, featuring seven originals and three covers; the title song was released as the first single, with “Last Goodbye” as the second. The video for “Last Goodbye” was chosen as a Buzz Clip by MTV, earning heavy rotation for a time in 1994. Though reviews were generally positive, sales were slow. Buckley seemed destined to have a cult following.

However, buzz around the album continued to build. Celebrities like Brad Pitt and music legends like Jimmy Page spoke of the album and Buckley in glowing terms. Buckley’s cover of Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” also began to leak into public awareness as it was singled out for praise in many reviews and started to attract the interest of Hollywood. Thought it wasn’t a hit out of the gate, sales for the record were steady, and anticipation for a new album began to build.

Jeff Buckley’s cover of Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah.” (Jeff Buckley / VEVO)

Sadly, that would never come to pass. He toured extensively for the next two years and worked with punk legend Patti Smith on her Gone Again album in 1996. During those sessions, he met Tom Verlaine, who had been the lead singer of Television. Buckley enlisted Verlaine to produce the new record and reconvened his band to rehearse his new material. Unfortunately, after a few recording attempts, Buckley wasn’t happy with the results; he contacted Wallace to replace Verlaine. Buckley sent the band on to NYC while he worked out the songs in Memphis.

The band returned on May 29, 1997. That night, Buckley went for a swim in Wolf River Harbor. The band’s roadie Keith Foti busied himself moving a guitar and radio back from the shore as a tugboat passed. When Foti looked back to the water, Buckley was gone. Search and rescue teams worked through the night, but Buckley’s body wasn’t found until June 4. The autopsy revealed no sign of drugs or alcohol, and his death was officially declared an accidental drowning.

“Everybody Here Wants You” by Jeff Buckley. (Jeff Buckley / VEVO)

In the wake of Buckley’s death, Grace went to achieve a totemic existence. His version of “Hallelujah” has been used in dozens of films and television shows, from The West Wing to NCIS. In 2014, Buckley’s cover was added to the Library of Congress’s National Recording Registry due to its artistic significance. Rolling Stone and VH1 include Grace in their lists of the Greatest Albums of All Time; it was also rated as the second favorite album in the entirety of Australia in the 2006 My Favourite Album special. Buckley is also enshrined in Rolling Stone’s list of the 100 Greatest Singers of All Time.

In 1998, most of Buckley’s remaining studio tracks and demos for the second album were compiled into Sketches for My Sweetheart the Drunk; The Onion’s AV Club accurately assessed that it was “frustratingly incomplete, but mostly remarkable.” The song “Everybody Here Wants You” was released as a single and nominated for a Grammy for Best Male Rock Vocal Performance in 1999. It’s mainly a snapshot of unfulfilled promise. Today, new audiences continue to discover Buckley through Grace and “Hallelujah,” which has continued to chart digitally throughout the 2000s. We’ll never know what Buckley might have accomplished, but his literal last goodbye left music that will be appreciated for years.

“Bwah-Wahdi-Dough” by Henry Anton Steig

Bronx-born Henry Anton Steig was a textbook Renaissance man. As a saxophonist, painter, cartoonist, writer, astronomer, and jeweler, the man of many talents was sewn into much of 20th-Century iconography without ever becoming a household name. His fiction appeared in The New Yorker, Esquire, and Collier’s, he worked with songwriter Johnny Mercer in Hollywood, and his Manhattan jewelry shop even played the background of Marilyn Monroe’s iconic subway grate scene in The Seven Year Itch. His story “Bwah-Wahdi-Dough” is a swinging New Year’s Eve affair with a complicated love triangle bursting with colorful city dialect.

Published on January 9, 1937

In the hallway of the apartment house, Harry Tack looked himself over carefully, brushed a bit of lint off the velvet collar of his form-fitting topcoat, and then rang the bell marked “Smith.” The door was opened by one who, he had decided, was a very cute number; not much over five feet tall — just about right for his own five-six — slimly and gracefully curved in a very special way, and with large dark eyes and amber-colored hair.

“Hello, Harry,” she said.

“Hi, Sue.” Harry followed her into the apartment.

Susan introduced him to her parents. They were in the kitchen, Mr. Smith reading, and Mrs. Smith knitting, and Harry was thankful that they remained there when Susan took him into the living room. He sat down in an easy chair, carefully putting some slack in his trousers first, and Susan sat opposite him on a couch.

“Must be nice having a night off from the trumpet,” she said.

“Oh, I never get tired of the piston,” Harry said. “I wouldn’t mind playin’ it every night ’na week, except when I got sumpm extra out of the ordinary on, like tanight.”

“Do you like clubbing better than steady work?” Susan asked, having acknowledged the compliment with a smile.

“Yeah, fra while, anyhow. Bill Devoe’s band’s got a pretty big rep, and Miller’s a good agent, so we’re kept on the go. It’s nice woik and we get it; fun playin’ to a different crowd every time. And with the Honeybunny hour twice a week and groovin’ plates for the Phonodisk Company, everybody’s happy far as dough’s concerned. How about you? Hodda you like clubbin’?”

“I’ve given up the idea of becoming an opera star,” Susan said regretfully, “so I have to like it. Trouble is, clubbing’s not very dependable.”

“I wouldn’t worry if I was you. Miller likes your woik, and you got a good contact with our band. It was just last week he started bookin’ you, wasn’t it? And you played two dates with us awready. That ain’t bad. ‘Fcourse, not everybody wantsa pay for extra entertainment outside of the band, but I wouldn’ be surprised if you knock off three dates a week on the average. And after a while maybe you’ll catch a wire too.”

“Radio would help a lot. Do you really think there’s a chance?”

“Well, there’s lotsa woiss singers than you on the air.”

That didn’t sound at all complimentary, and it made Susan involuntarily lift her eyebrows. Being informed, after some years of study, that her voice wasn’t big enough for opera or for the concert stage had made her somewhat unsure of herself. Looks, she knew, counted in this new work she was doing; she was not unaware of her attractiveness and of the obvious possibility that it colored people’s opinion of her as an artist. She wanted to be rated solely on ability. She had met Harry only twice, when she had worked with the band, and had talked to him for but a few minutes each time. When he had asked, simply, if he might come to see her, she had acquiesced, because she had immediately been attracted by his earnest manner and his frank, boyish smile, and because it was refreshing not to be subjected to the overture of wisecracks which she had come to believe to be a fixed Broadway custom. Harry seemed to be the sort who would be honest with her. She was a bit apprehensive of what his opinion might be, but, nevertheless, she took the plunge.

“Harry,” she said, “you’re an experienced dance musician, you’ve heard lots of singers of popular songs and you ought to know a lot about it. Tell me, do you like the way I put my songs over?”

“Well, look, kid,” Harry began, deliberatingly. “Do you want the oil or the real lowdown?”

“I want you to say what you really think, of course!”

Harry lit a cigarette, realizing that he had already committed himself to some sort of criticism. Well, Susan seemed really to want to know the truth, and he decided that it would be kinder to give her a good steer rather than the meaningless raves to which she was probably accustomed.

“Awright,” he said, “the lowdown. Here it is: You got a nice sweet paira pipes. And the voice does sumpm to the customers; otherwise, even though you are a cute package, Miller wouldn’ keep on bookin’ you. But there’s a million dames with good looks and nice straight voices. Some of ‘em even get inta the big dough. So what?”

“I’m listening.”

“Well, the point is you’re woikin’ with a swing outfit. Whyncha try to loin sumpm about swing?”

“But I’m not a trumpeter or a saxophonist. I’m a singer.”

“Whatsa difference?”

“Why, there’s lots of difference.”

“But there shouldn’ oughta be! A singer oughta think of ’erself like one of the instruments, specially when she’s woikin’ with a band. Why do singers hafta be corny? Odduv every thousand there’s maybe one — like Connie Boswell — who’s got the real mmph — you know what I mean — the real bounce, the real shake. The rest of ’m, well, insteada puttin’ a riff in where it belongs, they shake their elbows or their hips, or they say ‘hi-dee-hi,’ as if it was the woids insteada the notes that counts. ’Fcourse, the old poissonality hasta be there, and it’s much more important with a dame who’s singin’ than with a musician. But it gets me sore the way they fool the customers. Spose, when I had a solo, I jumped up and began wigglin’ around and playin’ icky — would that make me a ride man? Not by a long shot. Then why do they call a singer hot when all she’s got is a figger and maybe a cute way of flashin’ ’er lamps?”

“What would you want me to do — imitate Connie Boswell?”

“You could do woiss. Butcha don’t hafta imitate ’er. Study ’er stuff and get the feelin’ for it. And then you can start puttin’ your own stuff in. You don’t hear me imitatin’ anybody, do you? Inna beginning, I got all my stuff from Red Nichols and Louie Armstrong and a coupla others, and then, when I got kinda soaked in it — it got all mixed up, sorta, inside of me — it began comin’ out more and more different and original alla time.” Harry was getting excited. He looked hopefully at Susan, but sensed that there wasn’t much rapport between them on the subject. “I don’t know if I’m puttin’ myself across, kid. It’s hard to say what I mean, except on the horn.”

“I think I understand,” Susan said doubtfully.

“You hafta wanna give,” Harry said. “You hafta wanna get off on it, like Cab Calloway or the Mills Brothers.”

Susan stared at him perplexedly. The swing temperament, to her, was unfathomable. Swing musicians, as a group, were all very queer. They laughed at the strangest things; always seemed to be enjoying among themselves a joke the point of which outsiders couldn’t get at all. They belonged to a distinctive sect and appeared to be aware of it. Perhaps their attitude of lightheartedness was due, in. part, to the fact that they didn’t know what work — in the sense that her father, for example, pushing a plane and a saw all day, understood it — really meant. Their work was the happiest kind of play. No wonder they couldn’t be serious about anything. Perhaps Harry was different from the others in that respect. But she doubted that any subject — no matter how important — but swing music could inspire in him the intense enthusiasm, the almost religious fervor with which he had been talking.

“Look, Sue,” Harry said in desperation. “I can see I didn’t make it click yet. Forget about everything I told you and come over here to the piano.” He sat down at the baby grand. Susan stood at the upper end of the keyboard, facing him. “Now, I ain’t got much of a voice,” he said, “but I know how it oughta be done and I got enough control to give you some samples. Foist we’ll take one of the fundamental get-offs. In the old days it was ‘doo-wackadoo.’ Now it’s ‘bwah-wandi-dough,’ with a hotter swing. Get me?” Harry struck some simple chords. “Now sing. Bwah-wahdi-dough.”

Susan felt very silly. She blushed, swallowed a few times, and then sang the syllables.

“Again,” Harry said.

She sang them again and several more times.

“You don’t get the accent right,” said Harry. “Step on the ‘di,’ but cut it short.”

He demonstrated once more. Susan repeated it, but it still lacked fire.

“Well, I can see that don’t click either,” Harry said. “But maybe it will if I give you a longer phrase to hang on to. Here: Bwah-wahdi-dough. Mbee-mbah-mboodi … No, no. When you get to the sounds beginning with b, make your lips spring open — blow ’em open — it should be like a series of liddle explosions, and the mm’s tie ’em together.”

Susan, though anxious to learn, still didn’t get it. She stood there, doing things with her lips like a silly goldfish — but a very beautiful goldfish — until Harry began to forget about the lesson. He was debating whether to do to those lips what seemed, at the moment, had to be done, but just as he leaned toward her, there was a “Grmph” from the doorway. Mr. Smith was standing there.

“Pardon me,” he said, “but is there something wrong? Mrs. Smith was worried. Asked me to find out what those strange noises were. And I must admit I was a bit alarmed too.”

Harry and Susan looked at each other and burst into laughter.

“We’re laughing at ourselves, dad,” Susan explained. “Harry is just trying to teach me something about shake music.”

“Oh, I see,” said Mr. Smith, as he withdrew. But it was quite plain that he didn’t “see” at all.

“Try those b sounds again,” Harry said, standing up and facing Susan. This time he didn’t care in the least whether she did it right or not. As soon as she had pursed up her round, ripe, cherry-red lips, he pounced at them with his own. She drew back, but not quickly enough to make the frown which followed appear consistent.

“Gee, Sue, I hope you don’t think the whole thing was just a gag,” Harry said. “That wasn’t part of the lesson. I just couldn’t help it. Honest, I couldn’t. Are you angry?”

He was so palpably contrite, Sue’s frown vanished.

“Of course, I’m angry,” she said. And then she smiled, because she had to admit to herself that it wasn’t true.

Harry went home with two previously formed opinions strongly confirmed. First, that Susan was a knockout. But second, that, as far as swing was concerned, she just didn’t have what it takes. It was difficult to explain that to her. Everybody was talking about swing, but very few knew what it meant. There had been a time when it annoyed him that people insisted on thinking they did know. But not now anymore. He had learned that the most one could hope for was a few sincere appreciators. There were always the members of the band, of course, and once in a long, long while, an outsider. You could easily tell, looking over a crowd of dancers, which ones you were really reaching. The rhythm got all of them — that was fundamental — but it was just one or two couples who usually kept near the bandstand while they danced, straining their ears for the pretty little subtleties of swing music, who really “felt” it. You could see them respond — with a grin, a jerk of the head, a sudden quick step — to that funny scream on the clarinet, the bubbly gliss on the trombone, the metallic hiss of muted cymbals in a cleverly inserted beat between embellishments of the solo instruments. And when the dance was over and the dancers stood, panting and applauding, on the floor, you caught the eye of one of them, perhaps, and it was like a precious secret between you. The others would never know, and there was nothing anyone could do about it. One either had the gift for appreciation — it seemed as rare, almost, as the gift for creating hot music — or one had not. Susan happened to be one of those who had not. Perhaps it would have been better not to have started it at all — this business of singing hot. She had been getting along nicely without it. Why get her all upset and dissatisfied with herself about it? And who was he to try to meddle with the intangibles of personality and temperament? Better to leave things as they had been. She was a wonderful kid and he was in love with her. When that and the promise in her smile after the stolen kiss were considered, swing seemed of very little importance.

But Harry’s decision not to meddle further with Susan’s singing technique had been reached without consulting Susan. Her interest aroused, she begged for further coaching. Harry would have liked to take her places, but she wanted to stay at home and practice singing, and he had to consent. So the coaching went on, without any sign of improvement in Susan’s style. Until one night, Harry, made irritable by her insistence on singing when he wanted to hold her in his arms and talk about the future, lost patience.

“Oh, what’s the use, Sue?” he said, after a half hour’s repetition of some simple hot phrases which Susan made sound very chilly. “You ain’t got it and you never will get it. Sorry I ever brought it up.”

“But I thought I was doing pretty well,” Susan said, very disappointed.

“That’s the hell of it,” Harry tried to explain. “It’s like a trumpet I once knew. He was a good paper man — went as far as anyone could, just readin’ the spots — but there wasn’t a real hot note in his whole getup. He should’a’ known it, but, like you, he didn’t. All of a sudden he got the notion that he was a sender, and he began tryin’ to play gut-bucket. Bought ’imself all kindsa tricky mutes, wasted a lot of rough tone, and it didn’t mean a thing. He thought he was a second Bix Beiderbecke and nobody could tell ’im anything different. It was awright when he played straight — there’s a place for straight men in this racket — but his sposed-to-be hot stuff was so sad that it took the bounce out of every band he woiked with. He got to be such a pain that none of the leaders would give ’im a job. And still he wasn’ convinced — thought the whole world had it in for ’im. Well, now he’s with a long-underwear gang, all cornfeds, like him; sorta hypnotized theirselves inta thinkin’ they know the way to town. He gets along somehow, but would you wanna be like that? Havin’ people who really know what’s what laughin’ at you? Take my advice and forget what I tried to teach you and go back to the straight stuff.”

Susan had tried so hard! She recalled the last time she had sung with the band. After one of her numbers, she had looked to Harry for encouragement, but all she got was a sad smile, sympathetic, but one which told her plainly that she was as far as ever from attaining what he had tried to teach her. Now she felt hurt, humiliated, and angry.

“Maybe you’re right,” she said. “I always thought it was vulgar, anyway. All that noise and blah — cheap!”

Harry didn’t like having the art form to which he was devoting himself spoken of in that way.

“If that’s the way you feel about it — noise and blah, cheap and vulgar — why dincha stick to grand opera in the foist place?” he said. “You should be at the Metropolitan at least.”

Susan was very touchy about her former aspirations. “Cheap and vulgar,” she spitefully repeated. “That’s what it is — and lowbrow!”

“Galli-Curci speaking!” Harry scoffed.

That was too much for Susan.

“Good night, Mr. Tack!” Susan said stiffly.

Harry stood up, straightening out all of his sixty-six inches. “Foist, sour grapes, and now a crack at my name. That ain’t cheap, I spose! Well, lemme tell you, there’s been some tremendous shots in the Tack family. That name’s got class. It ain’t corny — like ‘Smith,’ f’rinstance!”

Susan began to splutter, but that didn’t stop Harry from grabbing up his hat and coat and stamping out of the house.

The next time Susan sang with the band, she completely ignored him, and at the end of the evening she went home with Bill Devoe, the leader. Harry told himself that she was only trying to make him jealous, punish him. They’d make up, somehow. They had to — why, he had been on the point of proposing to her! Surely she knew how much he cared for her, in spite of the stupid quarrel they’d had. But Susan continued to let Bill take her home, night after night, and Harry began to upbraid himself for having lost his temper. He should have remained cool and polite, and then she would have had no justification for her coldness toward him. He wanted to talk to her, to apologize — if only she would meet him part way, so that he wouldn’t have to feel that he was forcing himself upon her — but she continued, stubbornly, to ignore him. Well, he wouldn’t try anymore, he decided. She’d have to be the first to talk now. He could be just as stubborn as she.

One night after a job, while the boys were packing their instruments, he caught Archie Wallenhoffer, the pianist, staring at Susan as she went out of the hall, arm in arm, as usual, with Bill Devoe. Archie was a big pudgy mopy fellow whom, it seemed, nothing could stir up except a hot tune. Harry somehow had never imagined Archie in love, but he realized now that the state of his own heart had not increased his awareness of what was going on around him. How could any man help falling for Sue?

“You too?” he said to Archie.

Archie sadly nodded. “How about a good old bender?”

Harry thought that a good suggestion, so they went downtown to a certain little place they knew and got thoroughly cockeyed.

“What chance do we stand,” Archie asked, “when Bill’s nuts about ’er?”

Harry, in a more sober state, might have considered the “we” presumptuous. Even now it seemed a bit too familiar. But as one who had been rejected, he couldn’t protest, even though it did make the whole affair something less than exclusive.

“Bill’s got everything a dame wants,” Archie went on. “Looks, dough and fame. And we’re just a coupla musicians — a dime a dozen.”

“Guess there’s only one thing for us to do,” Harry said. “You keep slappin’ the keys and I’ll keep ridin’ the piston, and we’ll both try to forget about ’er.”

This newly adopted philosophy of resignation, however, helped neither of them. Because it would have been difficult to forget a girl like Susan without seeing her two or three times a week. The one way out seemed to be to quit the band and seek a berth elsewhere. It was a hard thing to do. Harry had known the boys for a long time and they were the best friends he had. But Archie liked the idea, and it seemed easier to carry out when there were two of them. They decided to wait until New Year’s Eve, which was only a few days off. The band had an important engagement that night. For Harry and Archie it would be a sort of farewell party.

Early in the clear cold evening of the thirty-first of December there stood on a midtown corner a small built-to-order bus which had lettered on its sleek shiny outside, “Bill Devoe and His Club Orchestra.” The boys frequently played at homes and clubs in the suburbs, and the agent had decided that, musicians generally not being the most reliable people in the world, a private conveyance would save him a lot of last-minute headaches. Of course, there was no assurance that none of them would never miss the bus, but it was much more certain than having them travel as they pleased. Besides, the bus was a good advertisement.

Inside it were all the members of the band but the leader.

“I hope Bill gets here pretty quick with that broad,” said Al, one of the saxophonists. “It’s cold sittin’ still like this.”

Archie gave Al a dirty look. “Someday,” the pianist slowly said, “you’ll gedda good paste on the puss and maybe you’ll loin that not all dames is ‘broads.’”

“Why, Archie boy, is she got you sunk too?” Al asked.

The others all laughed, and Archie thought it best not to carry the subject any further. Harry didn’t say a word. He understood Archie’s chivalrous gesture and sympathized with it, but he was also inwardly amused by it. Another bus carrying a load of entertainers pulled up at the curb behind them. Then Bill and Susan arrived, and both buses started off uptown.

“Never too soon,” Al said, taking a flask out of his pocket.

But Bill stopped him. “Put that away! We got a job to do, New Year’s Eve or no New Year’s Eve. There’ll be enough of that later on. I want you boys to be able to toe the mark — at least until the customers don’t know the difference anymore.”

“Kinda dumb, anyhow, bringin’ your own along,” one of the men pointed out to Al. “Don’tcha think the Burgess crowd’ll take care of that?”

The Burgess home, a million-dollar estate, was forty miles out of town, in the hills. Old Man Burgess, it was said, owned most of the hills too.

The bus rolled steadily along, its chained wheels, echoed by those of the bus following it, clicking against the cleared strip of concrete between endless snow banks. Harry and Archie were slumped down in a rear seat, their knees against the back of the seat in front of them, their hats pushed forward over their noses. They tried not to stare too much at Susan, who sat in the front part of the bus, talking with Bill and the others near her. Frequently her laughter tinkled through the car. She seemed to be enjoying herself.

Al unpacked his clarinet.

“How ’bout you, Harry?” he asked. “C’mon, take out the plumbing.”

Al and Harry, it was conceded, were the best swingsters in the band. But Harry wasn’t swinging now.

“Sorry,” he said. “But I ain’t in the mood. Don’t expect anything but corn outa me tanight.”

“Corn, on New Year’s Eve? Wanna break my heart? Say it ain’t so!” Al pleaded, and he blew a high run on his clarinet.

Harry saw Susan turn around and glance at him; it seemed, from her thoughtful expression, that she was going to say something to him, but she quickly turned away. It gave him hope, but only for a moment. “Probably accidental,” he thought. “She didn’t mean to look at me at all.”

The trombonist and the guitarist took out their instruments and joined Al. The three of them played and the others sang, laughed and joked. All but Harry and Archie.

“Don’tchoo guys realize it’s New Year’s Eve?” Al said. He got up and went to the back of the bus and blew his clarinet at them. “Smadda with you two boids, anyhow?”

“Lay off!” Archie angrily whispered. “‘Beat it!”

Taken aback by the fierce tone — it wasn’t like Archie to get sore at anybody — Al shrugged his shoulders and rejoined the merrymakers at the front of the car.

The evening was still young when the buses pulled into the driveway of the Burgess estate, but several young people, obviously intent on a good time and as much of it as possible, met them at the entrance to the huge house and gave them a wild loud welcome. They were ushered into a ballroom whose size and splendor made them think for a moment that they were in a swanky hotel. Soon they had unpacked, arranged themselves on the platform at one end of the room, and started a dance number.

By ten o’clock, the ballroom was pretty well filled. It was a gay crowd, the holiday spirit was contagious, and Harry gradually lost himself in the music and began doing justice to his trumpet. Archie, too, couldn’t help swinging in good style. At eleven, the entertainers took part in a previously rehearsed floor show, night-club fashion. There was a chorus of dancers, some comedians, a quartet, and some solo numbers. After that their work was done and the entertainers mixed with the crowd. It was as much their party as the guests’. Susan, though, continued working with the band, singing a chorus or two, now and then.

At midnight there was a tremendous din. The guests blew whistles and horns, rang bells, cheered, shouted, yelled and generally conducted themselves as was considered seemly for the first few minutes of the new year. The band played Auld Lang Syne, everybody got a bit maudlin, and then, with the help of servants who were constantly making the rounds with loaded trays for those who were too lazy to help themselves from the side tables, things began gradually to disintegrate.

At about 2:30, the additive effect of the many little sips between dances were beginning to tell on Harry. He sat in a corner near the bandstand with a glass in his hand, wondering whether he had had enough to drink. More, he decided, couldn’t make him any more miserable than he already was. He contemplated the color of the liquid in the glass, preparatory to tossing it off — just like Susan’s hair it was when the light caught it — and then Bill tapped him on the shoulder. Bill had been drinking too.

“Snap odduvit, Harry,” he said unsteadily. “We ain’t played a number in about a half hour. And we can’t find Archie. C’mon, help me find Archie.”

All the men in the band engaged in a search, and finally Archie was discovered where no one had thought to look for him — on the bandstand under the piano, asleep. Bill angrily reprimanded him.

“Whaddaya mean, bawlin’ me out?” Archie complained as they got him to his feet. “Wasn’ I here alla time, ready for woik? ’At’s me, Johnny onna spot!”

When the band was ready to begin, Harry suddenly got a bad chill and began to shiver.

“Hold it a minute, fellas,” he said, getting up and going into the anteroom. When he returned, he was dressed in overcoat, muffler, hat, spats and gloves.

“O.K. Now we can start,” he said, and flopped into his chair.

“Quit clownin’,” Bill said, angrily. “You’re spoilin’ the looks of the band. Whaddaya think we’re wearin’ monkey suits for?”

“But I got a chill, I tellya. Want me to catch cold and die?”

“We don’t start till you take those extra duds off!”

“Suits me!” Harry put his trumpet in his lap, folded his arms, leaned back and closed his eyes.

“You’re fired!” Bill said in a rage.

Harry opened his eyes, looked at Bill and began to guffaw. He turned to Archie. “Hear that, Arch? I’m fired!” and he laughed more loudly than ever, Archie joining in.

“Awright, wise guy; you’re fired too!” Bill said to Archie. “You’re both through after tanight.”

Now both Harry and Archie laughed quite insanely. But meanwhile people were demanding music, and Bill had to surrender to Harry’s whim. He raised his baton, brought it down and the band began to play, but he lost his balance and almost fell off the platform. Someone gave him a chair. He led sitting down for the rest of the dance.

Susan, standing on the bandstand while she waited for the beginning of a chorus she was to sing, looked around her in distress. She had seen some gay parties, but none before nearly so bacchanalian in spirit as this one. Only a dozen couples of the, hundred or so present were dancing. The others were gathered in noisy groups about the ballroom and in the corridors and on the glass-enclosed terrace which encircled the house. In the center of the ballroom floor, some men were trying to find out how many chairs could be placed one on the other without toppling, and three or four girls in the group were excitedly shrieking, in anticipation of a crash. The behavior of some of the other girls could hardly have been considered decorous. Susan felt very lonesome.

At the end of the dance, Bill remained in the chair from which he had conducted the band. His face was on his chest and his arms hung limply at his sides. The baton had slipped out of his fingers. His bow tie was undone. Susan stood studying Bill with her chin in her hand. She saw Harry, out of the corner of her eye, wander away from the bandstand, out on to the terrace. She looked at Bill again. Not very attractive when he was drunk. And what a nasty disposition — firing two of his men! Harry was drunk too. But they said a man’s true nature showed itself when he was drunk, and Harry hadn’t been mean, like Bill, at all. Just childish. And perhaps she was partly to blame. She had seen that sad pleading look in his eyes more than once, during the last week or two, when she had been sure that he didn’t know she was looking at him. And on the bus — she had wanted to say something then, just a few words, anything, to let him know she wanted to talk to him. But with Bill there, and the others, she hadn’t been able to. And all this evening he had seemed unapproachable. But what else could she expect, the way she had treated him? And now, Harry, poor boy, was ill. She felt she was to blame for that.

Harry found a comfortable divan between some potted shrubs in a quiet corner of the terrace toward the back of the house, and stretched himself out in it. He was sobering up, but he felt dizzy, weak and extremely-depressed. “Nobody loves me,” he hummed sadly. He sat there, staring out from under the brim of his hat into the cold blue hills for what seemed a long time, and then he heard footsteps.

“Harry?” a soft feminine voice came from behind the shrubs.

“Harry?” he heard again, as if in a dream, and Susan stood before him. She seemed worried and embarrassed.

Harry’s chill left him. He hastily removed his hat, muffler and gloves.

“We hafta play again?” he stammered, not knowing what else to say.

“No. It’s after four and the crowd’s thinning out. Mrs. Burgess is putting us up for the rest of the night. There’s plenty of room, and the girls thought it safer to wait here.”

“That’s interesting. But I think I’ll stay right here and watch the sun come up.”

It would be a beautiful sunrise over those snow-covered hills, Susan thought. And how nice it would be to watch it with Harry. He was looking questioningly at her.

“Well?” he said.

The light was dim, but Harry thought he saw her face flush.

“Why did you laugh like that when Bill said you were fired?” she blurted out.

“Really wanna know? Well, you see, Archie and I were gawna tell Bill, before the night was over, that we’re quittin’. Somehow we never got around to it, though, and when he told us we were fired, it struck us funny, ’specially because we were both kinda high, I spose. Now we don’t hafta tell ’im.”

“But Bill was high too. He didn’t mean it. And by tomorrow he’ll forget all about it. He’d never let you and Archie go if he could help it. You’re both too good.”

“Nice of you to say so. But I was gawna quit anyhow, don’tcha see?”

“Why?”

“Oh, there’s reasons. But look, Babe; does it make any difference?”

Susan pouted and looked at the floor. Harry tried to stand up, groaned and fell back on to the divan. Susan quickly bent over him.

“What’s the matter, Harry? Are you ill? I — I’ll bring you some hot coffee.”

“Naw, I don’ want any coffee, thanks. Sit down here and tell me what this is all about.”

Susan sat down next to Harry. Then Archie appeared.

“I thought so, pal. Seems like our deal is off,” Archie said, looking at them tragically. “But, well, I can’t blame you. Trumpets always was lucky stiffs. But pianists — ” He sadly shook his head. Then he smiled, as if something funny had suddenly occurred to him. “Well, pardon me for bargin’ in. Guess I’ll go find Bill and laugh some more at ’im. A good long laugh. He must be comin’ to by now.” Giggling in anticipation, Archie hurried away.

“Didja know Archie was groggy aboutcha?” Harry said.

“I wondered what he meant! No, I didn’t suspect it at all. He never said a word.”

“Tough on ’im. They don’t come any better than Archie. But let’s get back to us. Foist of all, what about Bill?”

“Nothing. Nothing at all. I thought I liked him. But going with him didn’t mean anything. Really it didn’t.”

“And where do I come in? Why the sudden thaw?”

Susan played with a decoration on her gown, avoiding Harry’s eyes. She didn’t know what to say. Couldn’t begin to put into words what she felt. Didn’t Harry realize that she had been fond of him all along? He wasn’t being helpful in the least, silently sitting there, waiting for an answer to his last question.

From inside the ballroom came the sound of blue, yet-not-unhappy piano music. Subconsciously, Harry began tapping his foot. Susan found herself tapping hers too. Then Harry reached for her hand and held it. That made it easier. “Fond,” she suddenly decided, was a very weak word. A deliciously ecstatic warmth crept over her, and all at once she knew what to do. She sang:

“Bwah-wahdi-dough. Mbee-mbah-mboodi.” This time it was very, very hot, and she went on from there with some stuff — it seemed to come out by itself — that even Harry had never heard before. He must have understood what she was trying to tell him because he didn’t let her sing much more, but interrupted with an invitation to a clinch which she accepted willingly — even eagerly, it might be said.

It turned out to be quite a sunrise.

Paul Whiteman’s Orchestra and the Future of Jazz

In 1926, Paul Whiteman and Mary Margaret McBride contributed a three-part Post series about jazz, which at the time had only recently become widely popular in the U.S.

In Part I, “Paul Whiteman Builds His Jazz Orchestra,” Whiteman details his early years and the events leading up to the formation of his jazz orchestra just before the start of the Roaring ’20s.

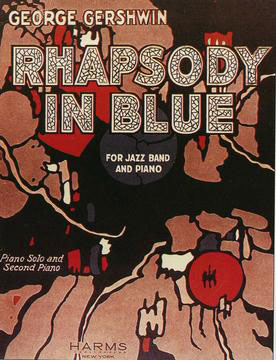

Part II, “Jazz History: Paul Whiteman, George Gershwin, and the Stale Bread Orchestra,” discusses Whiteman’s early commercial success — including his orchestra’s premiere performance of Rhapsody in Blue — and places jazz within the larger continuum of artistic music.

In this third part, Whiteman gives readers a closer look at the makeup of his jazz orchestra and his place as bandleader within it. Then he concludes his contribution to the Post with a last look at the future of jazz and jazz education in America.

This post was published to mark National Jazz Appreciation Month. You can read more of the Post’s historical stories from and about jazz legends in “Jazz History by Men Who Made It.”

Jazz, Part III

By Paul Whiteman and Mary Margaret McBride

Originally published on March 13, 1926

Invariably the layman is amused to discover that the saxophone and the banjo, both regarded by him as essentials to jazz, were not included in the original jazz band at all. As a matter of fact, the saxophone, which was invented more than 75 years ago by Antoine Sax, was designed as a very serious instrument. It was heard oftener in church than anywhere else, and the story goes that Mendelssohn refused to allow it in his orchestra because it was too mournful.

The original jazz band consisted of a piano, a trombone, a cornet, a clarinet, and a drum. The fundamental harmony and rhythm were supplied by the piano, the player of which could usually read notes. The other performers had no notes, so it mattered not at all that they had never learned to read music. They simply filled in the harmonic parts and countermelodies by ear, interpolating whatever stunts in the way of gurgles, brays, squeals, and yells occurred to them, holding up the entire tune, though still keeping in the rhythm.

Those days are gone forever, or nearly so. Considered musically, the ideal orchestra is one which will contain a quartet of every kind of legitimate orchestral instrument, thus permitting a four-part harmony in every quality of musical tone. Although this does not prove entirely practical, it is still an ideal which every orchestra leader today sets for himself. The result, I will venture to say, is that the United States has a greater number of efficient, economical, small orchestras than has ever been known anywhere else.

The jazz orchestra of today differs from the symphony mainly in the fact that the foundation of the symphony is its strings. All other instruments are added for tone color. In the jazz orchestra, the saxophone has been developed to take the place of the cello. In fact, it has been developed to such a high degree that it can be used for the foundation of the entire orchestra, taking the place of second violin, violas, and cellos. The saxophone, then, is in a way king of the jazz orchestra. Because of this, such demands have been made on the saxophone player that the manufacturers of the instrument have had to develop it to meet the new needs. It was a very different product 20 or even 10 years ago from what it is now.

Some demon statistician has estimated that there are now 10,000,000 saxophone players in the world. The estimate probably falls far short of the reality. And those amateur music makers who are not playing the saxophone have taken to the banjo. They say some great genius always arises to meet any national need. Is it any wonder that the soundproof apartment is now a glorious reality?

Musicians recognize four general classes of instruments in speaking of the orchestra — strings, woodwinds, brasses, and the battery of traps, chiefly instruments of percussion. Of the woodwinds, my orchestra has four saxophones; that is, four saxophone players; but all of these play saxophones in various keys — with clarinet, the oboe, the English horn, the heckelphone, the octavin, the accordion, and piccolo. Of the brasses, we have the trumpets, trombones, French horn, and tubas.

Perhaps the most important instruments of the battery are the tympani or kettledrums, the side or snare drums, the bass drum, the tambourine, triangle, cymbals, tom-tom, Chinese drum, castanets, rattle, glockenspiel, xylophone, marimba, clappers, and bones. Of these, we have the celesta, two tympani, snare and bass drum and dozens of fixings for our special effects.

Muting the Clamors of Jazz

So far this seems to me a fairly satisfactory concert jazz orchestra. We are always trying out new instruments and discarding old ones, so that I do not feel we shall ever be satisfied to become static. For a dance orchestra, eight violins are an unnecessary number of strings. Also one of the pianos may be omitted and an extra banjo added. At one time I tried out the organ for a dance orchestra, but found it too heavy and overpowering for the kind of music we make — rather dreadful, in fact. Another instrument we have used is the harp, which gives a pleasant effect in certain pieces but is not useful enough to make it worth having in the average small orchestra. In the double reeds, I am planning to add a bassoon.

Jazz players have become so adept at handling their instruments that they nearly make each do the work of two. The tricks of the trade rapidly become public property, especially if they are put on the records. Thus the discoveries go East and West, North and South, to enrich the orchestras in remote spots. Many jazz conductors and arrangers can adapt an orchestration from hearing a record played. I have heard some of our arrangements which bands had obtained in that way, and they were well played too. Such adaptation needs, however, a good musical ear and considerable technical knowledge. I am told that when a record is made by certain Eastern orchestras, arrangers for orchestras in the West and Middle West gather around for the first playing with paper and pencil.

The various stunts with mutes, though pretty well known to those in the business, are important enough to speak of in some detail. The chief kinds of mutes now manufactured are made of metal and cardboard. Before clever manufacturers saw the possibilities of these bits of material, the players themselves were using ingenious contrivances to get the same effects.

The first time I ever heard what I call the wawa mutes used with the cornet was, I think, when we did “Cut Yourself a Piece of Cake.” The players got that effect by inverting glass tumblers over the bells of the instruments.

One of our trombonists has a special mute, such as I have never seen before, by which he gets a beautiful graduation of sound very like the voice of a sweet human baritone [sic]. In the case of most cup-shaped mutes, the air goes in and comes out the same way, but with this one, the air goes from one chamber into another and out.

One interesting device used with the trombone I must mention. This is achieved by holding the bell of the instrument to the small end of a phonograph horn, with a result that has almost the qualities of a barytone [sic] voice. Some trick stuff is all right and some is in the very worst possible taste. For instance, a man who wires a mouth organ to his face as a solo instrument and uses the piano to accompany himself is making himself ridiculous. If your trick stuff is clever, use it. If not, keep away.

One of the qualities in the musician that the jazz orchestra has developed is ingenuity. If he feels that he needs a certain sound from his instrument, he puts his hand or his foot in it, or goes and gets a beer bottle, if nothing else is at hand.

The Derby Mute

The orthodox have, I think, been pretty well shocked by the employment of curious devices for altering the tonal quality of certain ancient and respected instruments. Somebody has suggested that this is because the mechanism is often rather baldly exposed. As a matter of fact, not nearly all the jazz stunts are new. For instance, the derby mute goes back to 1832, when Hector Berlioz directed the clarinetist at a certain passage in his Lelio, Ou Le Retour À La Vie, to wrap the instrument in a leather bag to “give the sound of the clarinet an accent as vague and remote as possible.”

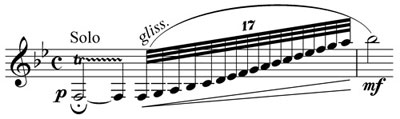

The glissando of the trombone occurs in the orchestral score of Schönberg’s Pelleas et Melisande, written in 1902 when jazz was as yet entirely unknown. Schönberg is also the father of the flutter on the trombone — that is, very rapid tonguing on the same note. And Stravinsky, in the days when jazz was still in its infancy, used muted trumpets. Yet jazz has developed much that is new, and this is its chief service to music. Music, like everything else, gets static in its development during any period when fresh tools are not being devised. From the way in which some of the jazz devices have been received, one might think that it was lese majesty [high treason] to make a pleasing sound in any way in which it had not been made before. Yet the development of music has gone hand in hand with the development of new instruments from the day when the savage first found that hitting a hollow log with a club made a sound that stirred human emotions.

There is a story somewhere to the effect that the man who first strung a gourd with catgut and made sounds upon it was put to death, because his fellowmen resented the introduction of a new noise into a world which they regarded as already overstocked with such. So you see there have always been cranks and reformers.

The Notorious Saxophone

The now notorious saxophone, in almost any of its sizes and keys, is one of the most useful of modern instruments. It is easy to learn — I believe there is a tradition that an ambitious boy can get the hang of it in 20 minutes — but difficult to master. But other instruments are still more difficult to master, and it is not necessary to master the saxophone to play dance music.

Saxophones supply the element of humor which American dancers insist upon having, and they are also extremely flexible, so that more or less difficult running passages may be played with ease. In skilled hands the saxophone is capable of smooth intonation in solo passages, though, like all reeds, the control of pitch is not easy.

With two or three saxophones for the same player, one may obtain a large variety of tone effects, shifting a melody into the deep bass with good effect, and then by picking up a smaller instrument, get a cold blue tone almost as pure as that of the flute. Or one may take the little top sax and push it up to super-acute register to make extremely funny noises. The collective compass of the soprano, alto, tenor, and barytone saxophones is a little more than four octaves, so there is sufficient territory for the complete performance of many pieces without the use of any other instruments.

The banjo, going on to the next typical jazz instrument, is of highest importance in our type of orchestra. Its tone is clear, snappy, and carries farther even than that of the piano. It is capable of rhythmic and harmonic effects that a leader is put to it to find in any other instrument.

You can get more pizzicato effects — you can get relatively greater volume with a single banjo than you can with a whole symphony load of violins and violas playing pizzicato, and you can play passages they wouldn’t dare to attempt. There is an example in a piece we used to be fond of playing, “On the Sip, Sip, Sippy Shore,” where “Turkey in the Straw” is introduced as a banjo solo. The pace is furious and the swift and flexible hands of the artist must move fast indeed. What symphony conductor would dare put such a passage as this in the hands of his strings? Yet the single instrument, in the dance orchestra, with one set of fingers is all that is required.

In the ensemble the banjo may be considered even more important than as a solo instrument. If it is a good timekeeper, it will tone down the piano, stop the traps from banging, and cause the whole organization, no matter how many instruments there are, to move on the beat like one man.

Obviously the jazz band has tried to develop extreme sounds. The deepest, the most piercing and the softest effects are produced, but any jazz-orchestra leader will soon learn that he gets his best effects if he plays softly. It is not necessary to bang to get your effect or to burst the instrument for volume. On the contrary, a good jazz orchestra is at its best and most seductive when at its quietest.

Made and Played in America

The early jazz was each man for himself and devil take the harmony. The demoniac energy, the fantastic riot of accents, and the humorous moods have all had to be toned down. I hope that in toning down we shall not, as some critics have predicted, take the life out of our music. I do not believe we shall. It seems to me that we have retained enough of the humor, rhythmic eccentricity, and pleasant informality to leave us still jazzing. And while we do not have so much unrestricted individualism as in the old days, every man must still be a virtuoso.

A critic has said that if jazz is to rise to the level of musical art, it must overthrow the government of the bass drum and the banjo and must permit itself to make excursions into the regions of elastic rhythms. Perhaps that is true. All I know is that if somebody will write us a different kind of music, we shall be glad to try to play it.

As I have tried to indicate, the modern jazz orchestra is an efficient arrangement. Every member knows exactly what he is to play every minute of the time. Even the smears are indicated in the music. Rehearsals are as thorough and frequent as in any symphony. The discipline of the orchestra, if it is a good one, must be complete. Yet there must be freedom such as I have never seen in any symphony. The men must get joy out of their work. They must have a good time and try to give their audience one.

Music is human. The character of the man that handles the instrument shows in his music just as his character shows in his handwriting. Every human being has his own value, his own character. It is when this variety is released into music that music thrives and grows. Jazz has forever ended the time when music was — to the average American — a series of black and white notes on white paper, to be learned by rote and played according to direction in a foreign language — staccato, legato, crescendo.

Americans know now that they may take any old thing that will make a sound that pleases them, and please themselves by expressing with it their own moods and characters in their own rhythms, thus making music. The saxophone, in spite of the fact that at one time it was used for church music, comes romping into the orchestra like a Wild Westerner into Boston society. Even the tin pan is not to be despised just because it was made originally to hold milk. Says jazz, put an old hat over a trumpet and make it sing as it never sang before. Who cares that it is only an old hat?

A Place in the Limelight

It was, after all, some very distinguished persons who started putting base agencies to work when they needed them. Schubert used to amuse his friends by wrapping tissue paper around a comb and singing the Erlking through it, and Tchaikovsky required the same implement to get his effects in the “Dance of the Mirlitons.” The highly respected orchestras of the ’70s employed cannon that broke all the crockery for miles around when they wished to get the effect of a battle.

The first essential of any good orchestra is that the human beings who compose it shall be musicians of the first water. But with a jazz orchestra this is not nearly enough. The players here must be masters not only of one but several instruments, so that a small group can produce the color and tone of a far larger one by doubling on two, three, or half a dozen instruments. Jazz players have to possess not merely musical knowledge and talent but musical intelligence as well, which is something else. In a symphony, the conductor’s is the only personality which stands out. In a jazz orchestra, every man is in the limelight. Therefore each man must be clever enough to sell himself to the audience. In other words, he must exhibit good showmanship by making his audience want what he has to give them.

He must have initiative, imagination and inventiveness amounting almost to genius. In the symphony, the composer invents. With us that job falls to the player. This versatile individual must also be young enough so that the spirit of adventure is still in him. He must be temperamental enough to feel and not too temperamental to be governed.

Perhaps the most important item of all is that each player must be an American. It is better if one is a native-born American and better still if one’s parents were born here, for then one has had the American environment for a lifetime, and that helps in playing jazz.

My men are of every kind of ancestry — Italian, German, French, English, Scandinavian. That does not matter. Nor does their religion. What does matter is that they are all American citizens and nearly all native-born.

I got a good many of my 25 men from symphonies. One of these is Walter Bell, who plays the bass and contrabassoon. He was in the San Francisco Symphony and has written two or three symphonies himself. He got his start playing the mandolin and guitar in an ice-cream parlor where the mice and rats were so thick that he had to put his feet upon a table to keep them from gnawing the leather of his shoes.

It was through him that I really got to know and like jazz, and I picked him for my own orchestra — mentally, of course, because I had no orchestra then and didn’t know that I ever would have — at a performance of the Symphony in San Francisco. Bell was playing bass, but the bassoon got sick and I, being the youngest member of the orchestra, was chased off to bring his instrument down for Bell to play. He played it and beautifully, but right in the midst of the Sixth Tchaikovsky Symphony, he commenced to play in all off rhythms — jazz, really. I don’t know why he did — just a crazy impulse, I suppose, to shock the staid symphony audience and curiosity to see how his experiment would sound. But right then I vowed that some day I’d have him in my band.

Another man we got from a symphony is Chester Hazlett, also of the San Francisco group. He was a first clarinet at 17 in a symphony, but he plays the saxophone for us because he has always been crazy about that instrument.

Frank Siegrist, trumpeter, and I played together in the Navy and experienced some of the difficulties of trying to supply eight orchestras to various company commanders when we only had the makin’s of four. But discipline was discipline in the Navy and nothing was impossible — that’s a Navy slogan — so we always managed somehow.

Henry Busse, trumpeter, is another symphony man. He has played in a number of the high-class musical organizations in Germany and knows the classics thoroughly. Yet it was he who stuck a kazoo in a regular mute one day and got an Oriental quality like an oboe that I had been trying to get for a long time.

Men taken from symphonies are the easiest ones to train. They have had good discipline, and they usually leave because they are interested in jazz and want to experiment along a new line. Their knowledge of music is valuable and they know their instruments.

The real blues player is more hidebound in his way than the symphony man. Blues are a religion with him, and he doesn’t think a man who is able to read music can really play blues.

Why Gus Left Us

I had a New Orleans boy, Gus Miller, who was wonderful on the clarinet and saxophone, but he couldn’t read a line of music. I wanted to teach him how, but he wouldn’t try to learn, so I had to play everything over for him and let him get it by ear. I couldn’t understand why he wouldn’t make an effort to take the instruction I wanted to give him. Finally I got it out of him.

“Well, it’s like this,” he confided seriously. “I knew a boy once down in N’Awleens that was a hot player, but he learned to read music, and then he couldn’t play jazz any more. I don’t want to be like that.”

A few days later Gus came to me and said he was quitting. I was sorry and asked if it was money. He said no, but stalled as to his real reason. Finally, though, he came out with it.

“No, suh, I jes can’t play that pretty music that you-all play!” Then in a wild burst of words, “And, anyway, you fellers can’t play blues worth a damn!”

Stars But Not Stardom

I choose my men according to the characteristics I have already set down, and I find them everywhere. Many of them come to me for tryouts. We have 40 or 50 applications for jobs every day in the New York office. My friends, too, scout around for me, and naturally I hear every orchestra I can everywhere I go. I catalogue the likely players I hear and the ones my friends tell me about. It’s rather like a baseball team. Sometimes I even take options on men.

The music business is just like any other. A doctor will recommend a doctor in another town to you if you are moving, and music men recommend cornetists and saxophonists in exactly the same way.

Our rehearsals are free-for-alls. Every man is allowed to give his ideas, if he has any, about how new pieces should be played. The orchestra makes a kind of game of working out effects that will go. In shirtsleeves if it’s hot, and even in bathing suits if it’s hotter, with sandwiches and cold drinks handy, we’ve been known to run over the appointed rehearsal time by several hours, due to interest in what we were doing.

There is very little stardom in my orchestra. We all work together for what we are trying to do. Star stuff can spoil any group. Cooperation can make a mediocre band go great. If inspiration comes to any one of the boys, we stop and jot down his recommendations. Some of the suggestions when tried prove to be no good, but I’d far rather have enthusiastic youth and a few mistakes in my orchestra than seasoned, too-careful old-stagers. The appeal of the jazz orchestra comes from spontaneity more than from finished brainy work. And for spontaneity, one needs wholesale youth.

I wouldn’t have a stolid man in my orchestra. The audience would feel a lack instantly. I think I’d fire a man quicker any day for a show of really surly disposition than for a serious mistake in musical execution. Not that my boys are never allowed to lose their tempers. Far from it. An occasional fit of temperishness is natural enough and comes with temperament.

An audience, by the way, can be the kindest thing on Earth or the unkindest. I never have faced an intentionally unkind one, but sometimes I have been greatly depressed by coldness and stand-offishness. An audience expects so much. People look at you, not as if you were a human being but just as something built up for their entertainment. They will never excuse a mistake and they make no allowances for your off days.

The players don’t glare or laugh when the audience applauds in the wrong place, but the audience will laugh or even hiss at a mistake. Perhaps, if they understood the handicaps actors and musicians often overcome at a performance, they would be more charitable. The other day I saw a dancer at a vaudeville house fall in a heap in the wings after her turn on the stage. An old sprain had suddenly become painful while she was doing a difficult whirl at the very beginning of her act, but she kept a smile on her face and went on dancing. She got a few hand claps, and very likely some former fan turned to his wife and remarked, “Well, I guess she’s getting old.”

Nothing to Do Till Tomorrow

A lot of folks wonder what a conductor is for. I’ve read plenty of comments by critics who speculated upon how much better certain orchestras might have done if they hadn’t been handicapped by a leader. Well, it’s a little bit immodest to say that an orchestra can’t do without a leader, but after all, it’s true. I wish the critics could once hear a leaderless orchestra. Only, of course, such a thing is not possible, for if the real conductor were removed another would rise from the ranks.

A band is like an army. It must have a commander. A good conductor must be a musician in every sense of the word. He should be able to play at least one instrument well and should understand the intricacies and possibilities of all the others he employs. He must be a judge of men, tactful, democratic and yet able to make his authority felt. He has to be a good showman and likable. If it is real and not a sham part of his personality, it won’t hurt if he is even a little eccentric on occasion.

As for the difficulty of jazz conducting — did you ever stand on a space 2 ½ x 2 ½ for just one hour? Try it sometime. There’ve been plenty of days when I’ve had to do that for nearly 12 hours almost at a stretch. For in conducting, you can’t move much farther than that off one spot.

Here used to be a typical day of mine in New York: I got up at 9:00 a.m., snatched a hurried bite of breakfast, and got to the office by 10:00. There was always a huge pile of correspondence to go over and attend to and considerable business for the string of orchestras I handle. At 12:00, we usually had a rehearsal or phonograph take. At 2:00, we played at the Palace, and in between we sandwiched in another rehearsal or recording session. At 6:30 we played at the Palace again, and after that the Palais Royal until 3:00 a.m., and finally bed with the same routine to get up to the next morning.

Moreover, this doesn’t include the necessary activities for publicity purposes, the interruptions by people who want jobs or come to have you hear them play or to ask charity of some kind. And I have forgotten to mention the benefits. I have sometimes played as many as 59 of these in 26 weeks. And yet a writer, who is also one of my best friends, said one day that my job is to “Just stand before an orchestra and pat my foot indifferently well!”

The secret of the success of modern dance music is in its arrangement. For unless the music is cleverly scored, the greatest musicians cannot make it popular with the public. Any man who is planning a career as a musician ought to know how to transpose at sight. Every score that comes to me is analyzed and dissected at rehearsal, down to the very last note. Naturally the small-orchestra arrangement will not always fit, so I take the music apart phrase by phrase. I find just where each melody lies according to the possibility of each instrument. Did you ever stop to consider that a single note on some trap instrument will carry away with it as much memory as 30 bars of senseless pounding?

Jazz orchestrations have done more to change the character of the jazz orchestra than anything else. The distribution of the music has been made definite, a balance has been kept between the choirs. The arranger distributes the parts to his orchestra, and here all his knowledge and wit are demanded.

The new demand is for change and novelty. Four years ago, a whole chorus could be run through with but one rhythmic idea. Now there must be at least two rhythmic ideas in a chorus and sometimes more. On the other hand, it is necessary to avoid overcrowding with material, for the melody must not be lost. “Noodles” — that is, fancy figures in the saxophone, such as triple trills — often crowd out the melody, and the thing to remember is that everything else is secondary to keeping this alive.

Early Jazz Records

When our first records came down from the laboratories of the phonograph company for their initial audition, a visitor exploded, “What the dickens?” Then he listened to a few bars — he was an experienced listener — and demanded, “Who?”

For years before we began to record, it had been necessary for almost all the recording laboratories to change the instrumentation of nearly all orchestral pieces. Certain instruments, notably the double basses which we then used, the horn, the tympanum, and in lesser degree other instruments, failed to yield satisfactory results. The double basses frequently were discarded and replaced by a single tuba. Modifications also in the placing of the orchestra were necessary in order to make the volume of tone from a large number of instruments converge upon the tiny diaphragm whose vibrating needle inscribed upon a disk of wax the mysterious grooves which, retraced by a second needle attached to a second diaphragm, gave back the voices and accents of music.

So, for all our labor and study, we had to go into the recording room and learn all over. One of the changes we made when we found that ordinary drums could not be put on the record was to use the banjo as a tune drum. The tympanum and snare drum record, but the regular drum creates a muddy and fuzzed-up effect when other music is going, although solo drums make very good records. This was when I tried out the banjo for the ground rhythm and discovered the possibilities of that small instrument, which until then had been kept in the back and hardly heard at all. We also discovered that almost every instrument has a treacherous or bad note, and that when the score calls for that note the instrument had better stop playing. An extreme dissonance would mean that the record would be blasted. For all our troubles, however, we were told that fewer changes had to be made in our scoring than in any dance records of the time. As a rule we made two records at a sitting, though once I believe we made nine in three days. Each record averages about an hour and a half or two hours, for there must first be a rehearsal and a test before the perfect record is passed upon by the company hearing committee.

Recording is perhaps the most difficult task in the day’s work — or the lifetime’s. A slip may pass unnoticed in concert, whether across the footlights or over the radio, and even if noticed it is forgiven, since living flesh and sensitive will cannot always achieve mechanical perfection.

But a slip in a record after a time becomes the most audible thing in it. Everything else will be neglected to wait for the slip and to call the attention of someone else uninstructed in music to some great artist’s false note. So every composition has to be recorded until it is perfect. If things go well from the first, well and good; but if, from the three records of each number usually made, there is none which will quite pass the exacting standards of the committee, there must be another afternoon of making and remaking. Every faculty of the artist, emotional as well as physical, must be expended in producing a perfect result.

In late recording practice, with highly improved methods of capturing sound and with new scientific principles, it has grown more and more practicable to record large bodies of instruments without losing volume, without having a large quantity of tone dilute and diffuse itself before reaching the actual part of the recording apparatus.

In the laboratory, the possibilities of the orchestra began to loom large and the original plan with a single player to each type of instrument began to expand. The saxophone, for instance, had always had a shadow or understudy. A third saxophone now was added and in time the orchestra developed the full Wagnerian quartet of instruments in this one group. The one trumpet was reinforced by a second, and the now popular combination straight and comedy trumpet team came into existence. The banjo instead of just marking time began to make new excursions into the realms of rhythm, and the fox trot began to change, without, however, disturbing the pedestrian order of things.

Not all these changes took place, of course, in the laboratory. Most of the rehearsing and discussing and restoring was done in consultations outside — consultations not always free from the heat of argument. The actual business of recording is a star-chamber matter, but it is no violation of a secret to admit that some of our early records were spoiled by men swearing softly at themselves before they learned the new adroitness which the delicate mechanism of the recording room required.

One sees all one’s friends and some of one’s enemies at the recording laboratories, and the exchange of experience between the classicist and coon-shouter, the string quartet and the clarinet jazz band is illuminating for everybody.

By and for Americans

What will be the end of jazz? I don’t know. Nobody knows. One may only speculate. But the speculation is fascinating business, and perhaps my ideas on such a nebulous subject are as likely to be sound as the next man’s. However, I am no prophet. I can only say what seems to me possible and a very little bit probable. First of all, jazz has a chance because it is a sheer Americanism. Artistic Europe grants this and applauds. Have Europeans ever accepted any other music of ours? Alas, no! The truth seems to be that we have assimilated the arts of Europe and yet made none of them our own. It is something to branch out at last for ourselves in music as in other efforts. That does not mean, of course, that when we branch we create art immediately. But then neither does the fact that many look upon jazz as a sort of artistic blasphemy mean that it is so. We jazzists might reply to those who are shocked at what they call the bizarre sounds evoked by our instruments as Turner did to his lady critic.

“Mr. Turner,” said the dame, “I never see such colors in the sunset as you see.”

“Don’t you wish you could, ma’am?” reparteed the painter.

Turner was a decade ahead of his generation and knew it. Perhaps we jazzists are a little ahead of ours. But I must confess in all humbleness that we have moments when we doubt this as much as any of those who cavil.

There is one thing about jazz—it must be played by Americans to be really well played. That means a chance for American musicians. The most encouraging symptom in the whole situation is the interest that high school and college boys take in jazz. Some day it will be with jazz here as it is with the races in England. Everybody who can scrape together a few shillings goes to the races. They’re a national institution. Jazz is becoming an American institution.

Every boy, whether he is normally musically inclined or not, wants to learn to play something. Jazz has given him the opportunity and something is going to come of this. Perhaps that something will be a new art. Certainly it will be a good deal of musical composition, some of it very bad, and some of it, I hope, very good.