The Debt and Death of Thomas Jefferson

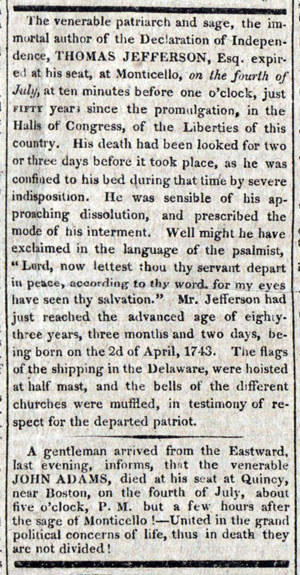

The news in the July 8, 1826, issue of the Post must have seemed incredible: “the immortal author of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson, Esq. expired at his seat, at Monticello, on the fourth of July, at 10 minutes before 1 o’clock.”

It scarcely seemed possible that 83-year-old Jefferson had lived just long enough to reach the 50th anniversary of America’s independence.

While readers were taking in this news, they would have been astounded to read in the next column: “A gentleman arrived from the Eastward, last evening, informs us that the venerable John Adams died at his seat at Quincy, near Boston, on the fourth of July, about 5 o’clock p.m., but a few hours after the sage of Monticello! United in the grand political concerns of life, thus in death they are not divided!”

The report continued, “On the morning of the Jubilee, he awoke at the ringing of the bells and the firing of cannon; the servant who watched with him said, ‘Do you know, Sir, what day it is?’

“‘O yes!’ he replied, ‘it is the glorious 4th of July — God bless you all.’”

Just an hour before his death, visitors asked him for a toast, which they could give that evening. He said, “I will give you ‘Independence forever.’”

A woman present asked him if he wished to add anything.

He answered, “Not a syllable.”

At his death, John Adams was able to bequeath land and books to start a school in his town of Quincy, Massachusetts. Years before, he had faced financial ruin when his London bank collapsed. Fortunately, his son, John Quincy Adams, came to his rescue by selling one of his houses and cashing in several investments. By his action, he left his father free of debt and still in possession of 275 acres of land.

(Courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

Down in Monticello, the end for Thomas Jefferson wasn’t as serene. Readers of the Post knew that Jefferson had spent his final months trying to free his estate from debt before he died. According to Thomas Jefferson Randolph, his grandson, the former president’s debts exceeded $100,000.

Jefferson had struggled with debt most of his life. To some degree, he was responsible for his financial troubles. He loved good living and he’d spent a fortune building and furnishing his mansion, Monticello. And, as he admitted to grandson Randolph, he hadn’t been skillful manager of his estate.

But he’d also been hurt by “the unfortunate fluctuations in the value of our money, and the continued depression of farming business.” Jefferson’s income was closely tied to those of his neighbors, since he was a creditor was well as debtor. When a poor growing season kept neighboring planters from repaying their loans to him, Jefferson would sink deeper into debt.

Some of his debtors had repaid his loan in Continental currency, but once America had become independent, the British merchants to whom Jefferson owed money would no longer accept these dollars in payment.

Jefferson had also been saddled with a sizeable debt inherited from his father-in-law. And in 1817, a friend asked Jefferson to endorse notes to repay a $20,000 debt. The friend died without clearing the debt, and that amount fell to Jefferson.

Many of the Founding Fathers had similar money troubles; George Washington and James Monroe died in debt. So did Alexander Hamilton, who was so poor that mourners at his funeral had to pass around a hat to gather the cash needed to bury him.

The social leaders of the new country might have been land-rich — Washington, for example, owned over 35,000 acres — but with few cash buyers of land, they had trouble applying their wealth to their debt.

Jefferson realized that, unless he cleared his debts, his daughter would have to follow his path, continually fighting for financial independence. Creditors had refrained from hounding Jefferson for repayment, out of respect for one of the nation’s architects. But they might not be as considerate to his daughter.

Desperate to raise money, Jefferson hit upon a unique solution. He and his grandson, Randolph, would run a lottery. The winner would gain title to Jefferson’s lands, including his beloved Monticello, which he had built over the course of 56 years. It was appraised at $71,000 ($1.5 million today.)

In April, the Post reported, “Messrs. Yates and McIntyre [of New York city] have the management of Mr. Jefferson’s lottery. There are 11480 chances at $10 each. The books for subscription were opened at Washington on Saturday, and it is said the tickets will be ready for delivery in a very short time.”

Jefferson was pleased to learn the country’s initial response to his scheme was generally positive. Yates and McIntyre had even agreed to run the lottery without charging a fee. Furthermore, the Post reported, “Lottery brokers are to sell the tickets without profit.” One Baltimore citizen had begun urging his fellow citizens to buy tickets and then burn them on July 4th , enabling Jefferson to pay off his debts and keep his property.

But then, several prominent citizens in New York proposed that Jefferson abandon the lottery. They said they would launch a fundraising campaign that would pay his debts without his losing his lands. Jefferson agreed.

But the campaign raised only $16,500 before it was ended. Jefferson asked that the lottery be revived. But now the initial enthusiasm had faded. Ticket sales were disappointing.

Fortunately, Jefferson died without knowing that his scheme wouldn’t work. He had only heard news of broad support from across the nation. He could now look back on his life with contentment. In a letter to his grandson, reproduced in the Post, he wrote that he had no reason to complain about his money worries, “as these misfortunes have been held back for my last days, when few remain to me. I duly acknowledge that I have gone through a long life, with fewer circumstances of affliction than are the lot of most men. Uninterrupted health, [sufficient money] for every reasonable want, usefulness to my fellow-citizens, a good portion of their esteem, no complaint against the world, which has sufficiently honored me, and, above all, a family which has blessed me by their reflection, and never by their conduct given me a moment’s pain. And, should this my last request be granted, I may yet close, with a cloudless sun, a long and serene day of life.”

After his death, lottery ticket sales fell sharply; Americans weren’t as enthusiastic to help Jefferson’s heir. And now several states were raising objections to the scheme. By 1828, Randolph conceded the project had failed.

Jefferson’s estate, and debt, were inherited by his daughter, Martha Washington Jefferson Randolph. She soon began selling off the estate. She was forced to sell Monticello in 1831. She also sold the 130 slaves still held on the estate.