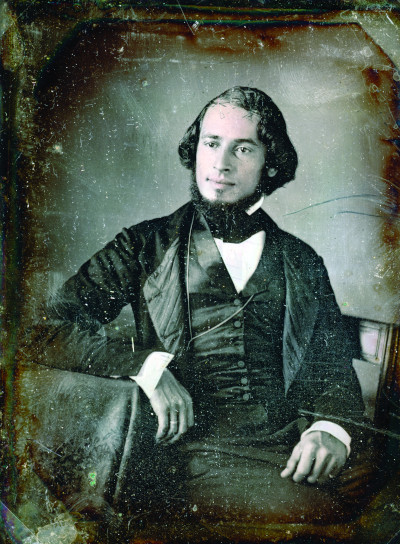

The Earliest Photo of Native Americans

On a cold day in late November 1853, in a place called Big Timbers, in what is today southeastern Colorado, a Jewish photographer named Solomon Nunes Carvalho hoisted his 10-pound daguerreotype camera onto a tripod and aimed his lens at a pair of Cheyenne Indians. At first glance, the resulting image, scratched and faded from years of neglect, seems unremarkable. But in fact it is probably the oldest existing photograph of Native Americans taken on location in the Western United States. It’s the sole surviving daguerreotype from an unprecedented and extraordinary photographic journey. And for me, a filmmaker chronicling Carvalho’s incredible but little-known story, it ultimately provided a powerful spiritual bridge to the past.

Carvalho was 38 years old and an unknown portrait artist and daguerreotypist when he received an offer from Col. John C. Fremont, the most famous adventurer of the day, to serve as the official photographer of Fremont’s Fifth Westward Expedition. For years, Fremont had been consumed with mapping a route for the transcontinental railroad. He had always included a sketch artist among his crew, but this time he wanted to use photography, a new technology, to document the terrain.

An urbane city dweller raised in Charleston, Carvalho had never traveled West or even saddled his own horse.

It was a risky proposition. Fremont’s previous foray had ended in disaster when 10 men froze to death in the Rockies, and Carvalho was totally unprepared. An urbane city dweller raised in Charleston, South Carolina, he had never traveled West. In fact, he had never even saddled his own horse. No daguerreotypist had ever attempted anything like this before. Daguerreotopy, which was the earliest form of photography, had only been invented 14 years earlier in 1839. It was a cumbersome process involving polished, silver-coated copper plates and lots of gear and chemicals, and it was prone to failure. Of the handful of professional daguerreotypists in the United States, nearly all worked indoors, shooting portraits. Capturing wide landscapes in extreme weather conditions was almost unheard of.

Yet two weeks after accepting Fremont’s offer, Carvalho set out, with a seasoned group of explorers, teamsters, hunters, and guides. It would be the journey of his lifetime. The team included white Americans, a German, a few Mexicans, 10 Delaware Indians, and of course Carvalho, who was an observant Sephardic Jew of Spanish-Portuguese descent. From the very start, the group faced challenges: torrential rains, raging prairie fires, injuries, infighting. Col. Fremont became injured early on and had to turn back to seek medical attention. After a six-week delay, Fremont rejoined his men in Western Kansas and then led them, perhaps foolishly, toward the Rocky Mountains just as winter was about to set in.

Along the way, Carvalho dutifully worked at his craft and, against the odds, succeeded in capturing image after image of the landscapes, buffalo, and the expansive terrain of the West.

The expedition encountered the Cheyenne village at Big Timbers in late November, during a supply stop along the Santa Fe Trail. It wasn’t easy photographing the Native Americans, Carvalho found. “I had great difficulty in getting them to sit still, or even submit to having themselves daguerreotyped. I made a picture, first, of their lodges, which I showed them,” he later wrote.

Carvalho’s daguerreotype of Big Timbers shows a pair of teepees nestled up against the edge of a forest of tall pines. Atop a thicket of logs and tree branches, several skins or hides are set out to dry. Two human figures, faded to an almost ghostly pallor, anchor the image in time. Their faces are hard to make out, but one has long braids and both are dressed in traditional native outfits.

Princeton historian Martha A. Sandweiss, an expert in photography of the American West, credits Carvalho with creating a painstakingly deliberate scene. “Carvalho sensed he needed to preserve a certain amount of information,” she told me in an interview. “He stepped back from the scene, and he has carefully framed the image. He’s not doing a close-up, at least in this picture, of the two people, or of the teepee, or of a piece of meat on the ground. He’s trying to show us something about native life.”

Fremont was thrilled with Carvalho’s work. “We are producing a line of pictures of exquisite beauty, which will admirably illustrate the country,” he wrote to his wife, Jessie Benton Fremont. He described the pictures of Big Timbers as “jewels.”

“I had great difficulty in getting them to sit still,” wrote Carvalho about the natives he photographed.

Sandweiss believes the daguerreotype tells us as much about the photographer as it does the subject. “I think what we see in this picture is evidence of a collaboration. It’s important to remember that Carvalho was working with a camera on a tripod. This is not a snapshot. These Indian subjects knew they were being photographed, and they are looking Carvalho in the eye.”

Of the 300 or so daguerreotypes Carvalho made on the expedition, this image is the only survivor.

After the expedition, photographer Mathew Brady’s New York studio converted Carvalho’s daguerreotypes into hand-drawn printing plates, so they could be turned into etchings and published. At the time, converting photographs to etchings was the only way to reproduce them for large numbers of people to see. It seems inconceivable to us today, but at that early time in photographic history, the daguerreotypes themselves were considered worthless — just a means for carrying back visual information that would be enshrined forever on a steel printing plate. Years later, they ended up in a storage unit belonging to Fremont and were destroyed in a fire in 1882 — gone forever, and barely missed. The Big Timbers daguerreotype somehow, luckily, ended up in Brady’s personal collection, which now resides at the Library of Congress.

The 60-odd surviving etchings made from Carvalho’s daguerreotypes tell a spectacular story of discovery, but the one surviving image does more: It provides a spiritual connection to the past. For most of the years I worked on my documentary film, Carvalho’s Journey, I relied on various reproductions of the Big Timbers image. I finally had a chance to see the real thing during a visit to Washington, D.C.

It is smaller than I had imagined, just four by five inches. In real life, the damage is worse than in reproductions. But holding it in my hands, I was struck by an intense proximity to history. This piece of copper was the same tool that miraculously captured the Cheyennes’ likenesses, their teepees, their hides drying on the line. It was the same bit of metal that an urbane, Southern-Jewish photographer carried thousands of miles on horseback and heated over a fire to develop. The moment captured on the plate, faded as it is, was the exact image Solomon Carvalho saw that day. Native people who had never seen a photograph before — and whose lives would never be the same after their collision with Europeans — would have seen it too. It was the vessel through which an unlikely visitor and a pair of Indians faced each other and forged a quintessentially American encounter.

Daguerreotypes, which are in many ways an art form lost to history, are reflective just like mirrors. On one as faded as Carvalho’s, the mirrored surface makes it almost impossible to see the image detail when you look directly at it. You instead see yourself, peering into it, looking into history.

Steve Rivo is a documentary filmmaker and television producer. He is the writer and director of Carvalho’s Journey (2015). More info at www.carvalhosjourney.com. This essay is part of What It Means to Be American, a partnership of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and Zócalo Public Square.

This article is featured in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: A glimpse of the past: The only surviving daguerreotype from Solomon Nunes Carvalho’s 1853 journey west depicts a view of the Cheyenne village at Big Timbers. Two figures stand to the left; drying hides hang on the right. (Library of Congress)

Jewish Pawns

The story has a familiar ring to it. Thousands of refugee children seeking asylum in the United States sparks a heated debate over immigration and human rights.

Today the children are illegal entrants from impoverished regions of Central America. In 1939, they were Jewish children whose parents had been shipped off to Hitler’s concentration camps.

That year, U.S. legislators introduced a bill into Congress to allow 20,000 of these children to enter America. The bill’s sponsors believed that, unless these children were allowed to emigrate, they would suffer the same fate as their parents.

The bill was defeated when Congress voted in accord with American opinion; at the time 60 percent of voters didn’t want to raise immigration quotas for Jews fleeing the Nazis.

We might wonder how Americans could turn their backs on children facing almost certain death. But Americans weren’t heartless in those days, they were afraid. Many feared the children’s parents would eventually petition to join their children and would arrive in the U.S. to take jobs away from Americans. After all, unemployment in 1939 was still lingering near 17 percent.

Some feared that allowing these young refugees into the U.S. would damage its status as a neutral nation, particularly in the eyes of Germany. Others feared the children would introduce non-traditional culture into American society.

Some were hoping to keep all traces of Europe’s troubles out of America.

And many, alas, just disliked Jews. If anti-Semitism hasn’t declined in America in the past 75 years, it has certainly become less outspoken. But in 1939, many anti-Semites weren’t shy about expressing their dislike of Jews.

Many Americans, though, were simply indifferent, reluctant to intervene in Germany’s treatment of its Jewish population. They regarded Hitler’s brutal treatment of Jews with cold detachment as Demaree Bess did in the Post on March 18, 1939.

“There are two manners of approach to this important question. One is emotional, coming from the heart. The other is intellectual, coming from the head. In America, we have thus far stuck largely the emotional approach. Our hearts have been profoundly moved and our sense of decency outraged by the barbarous persecution of thousands of helpless men, women, and children. Many of us have become so indignant that we are in a mood to do something — anything — to retaliate against bullies and brutes.” (Read the entire article “Jewish Pawns in Power Politics” from the Post.)

Bess was worried that “anything” could mean going to war with Germany. So he encouraged readers to think about anti-Semitism as something other than the systematic abuse of a religious minority. It was also, he said, a political tool. In Germany, it had helped the Nazis distinguish themselves from other socialist groups and gather a following among bigots and bullies. Anti-Semitism had also enabled the Nazi Party to enrich itself from the penalties they inflicted on Jews as well as the theft of imprisoned or executed Jews.

In a surprising move, Bess, reported Italy had also adopted racial laws against Jews, despite the fact that Mussolini long maintained that anti-Semitism was senseless. Japan, which had virtually no Jews to hate, had also made anti-Semitism part of its national policy.

Italy and Japan only adopted the Nazi policy to attract anti-Semitic allies in other countries. In the Middle East, for instance, Italy was hoping to stir up opposition against Britain and its colonies, but it had agreed not to engage in any anti-British propaganda. With an anti-Jewish campaign, it could still rally support among Arabs. Italy’s new anti-Jewish laws, Bess wrote, “served as the most effective kind of propaganda among all those countries and groups which dislike the British because they are pictured as defenders of the Jews.”

Japan’s big worry in 1939 was the Soviet Union. Russian troops continued to threaten Japanese forces in Manchuria. At the time, the communist government in Russia was widely considered to be friendly to Jews.

Japan hoped to reduce Russian troop concentration in Manchuria by forcing the Soviet Union to shift armies west against opponents in Europe. “Japanese agents,” Bess reported, “working among anti-Semitic groups in Eastern Europe [that engaged in] various anti-Soviet movements, finally realized, like Mussolini, that they could make better progress if their government were definitely committed to a policy of Jew-baiting.”

While this is informative, it hardly seems to address American outrage over Nazi atrocities. And it raises the question of whether it is appropriate to consider some issues “intellectually.” A truly detached inquiry would involve accepting nothing and questioning everything, so that you might raise the question, as Bess did, “Are the Jews themselves responsible for arousing the hostility of other groups? Are they guilty of all those sins with which they are charged by anti-Semitic groups in all parts of the world?”

Precisely the sort of questions Hitler would want you to ask.

Step into 1939 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 75 years ago: