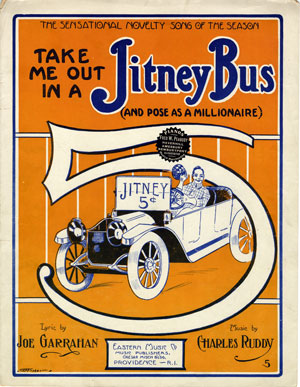

Will Uber Share the Jitney’s Fate?

You’ve read the story before: A transportation startup staffed by a fleet of independent car owners challenges established public transit, and controversy begins.

The story concerns ride-sharing service apps like Uber that allow independent drivers to find their next fare and offer travelers an alternative to traditional taxis. Launched in 2009, Uber Technologies Inc. has grown into a $40 billion international business. And understandably, traditional cab companies, whose workers are still required to pay fees and meet licensing requirements that Uber drivers avoid, resent the billion-dollar corporation. In response to the outcry, some cities and even countries have banned Uber from their streets.

A similar story was published 100 years ago in the Post, regarding the rise of the jitney business.

In a 1915 article “The Jitney Juggernaut,” author Will Payne claimed the nationwide phenomenon was started by L.R. Draper, a car salesman. For weeks, Draper noted a growing number of people waiting for the First Street trolley car. So, one July morning in 1914, he put a sign in the window of his car declaring his intention to take passengers to Boyle Heights, three miles away, for a “jitney” — that is, a nickel.

Later that month, “two or three other enterprising persons, having leisure and a low-priced automobile, hung signs on the latter and followed in Mr. Draper’s footsteps, covering the same route,” Payne wrote. By August, at least four additional drivers were taking passengers from First Street to Boyle Heights. Some started taking passengers along other routes in the city. By October, there were about 30 jitneys in LA.

Then the business really took off.

LA unemployment was high that year, and secondhand Model Ts were available on easy terms. Operating a jitney must have looked like a profitable venture because by mid-November, Payne noted that “well toward a thousand 5-cent autos were plying the streets.”

He estimated that jitneys were taking in over $1 million a year (about $23 million today). Around 75 percent of that was income lost by the streetcar company, which complained that the jitneys were unfair competition. The “trolley people,” as Payne called them, claimed they couldn’t adjust their operating costs to make up for the lost riders. They would need to sell off rails, electric cables, and cars to balance their losses; the jitney owners had only invested their cars.

The trolley people also pointed out that jitneys were seriously adding to the city’s traffic problem, particularly when they gathered around at the street corners where trolley cars stopped.

But commuters found jitneys a cheap alternative to crowded cars and long waits. Every day, Payne estimated, over 60,000 people chose to take a jitney to work instead of the trolley. The jitneys were faster, could slip through traffic, and didn’t stop at every street corner for more passengers. They were so affordable that businessmen were taking rides home for lunch instead of dining at restaurants close to the office.

“The jitney’s defense and justification,” Payne wrote, was “that people want it; that it gives them a better article for their money than they got before.”

Commenting on the crowded cars, the editors of the St. Louis Post Dispatch hoped their ridership would continue to fall until the streetcars would “find themselves able to provide a seat for each passenger who buys one. The jitneys may even achieve the miracle of making traction magnates understand there is a limit to the patience of the American people.”

Naturally the sudden growth of jitney transit sparked controversy. The jitney wars, Payne wrote, “produced estrangement between friends and icy looks across bank counters. It would no doubt have divided brother from brother if two brothers had taken opposite views of it. … On the one hand is the new industry, struggling to live, and on the other hand are powerful opponents who want it to die. A man’s standing in the community can almost be determined according to whether he is pro-jitney or anti-jitney.”

The streetcar company was understandably opposed to jitneys. But so were many people Payne met who disapproved of carpenters, plumbers, salesmen, and others who’d started their own jitney businesses. They felt it was “simply monstrous for a lot of fellows to bob up and put a dent into a $25 million street railroad.”

Hearing the trolley people’s complaints, the LA City Council passed an ordinance that would regulate, and probably discourage, the new transit providers. The ordinance required drivers to procure a license, buy insurance, pass an exam and driving test, equip their rear wheels with nonskid tires or chains in rainy weather, and unload their passengers 50 feet from street corners when traffic was heavy. Each jitney had to display a conspicuous sign announcing its route, and no other advertising. Drivers could not stray more than three blocks off their routes.

Two more conditions are of particular interest. The first required “no passenger shall be refused on account of race or color.” The second condition was that every jitney should have a light above the backseat, “lest sentimental passengers take advantage of the dusk to spoon, spooning being a crime unknown on the Coast before the advent of jitneys.”

The mayor vetoed the ordinance because “it did not go far enough in the way of regulating jitney traffic.”

Surprisingly, the jitney owners supported many of the regulations the City Council proposed. However, they wanted a cheaper license fee, no insurance requirement, and — it is significant to note — they opposed being compelled to carry any passenger, regardless of race.

The trolley car company might have been losing thousands every day, but the jitney drivers weren’t getting rich. Payne doubted that a driver made more than $3 a day ($70 today). These “moderate wages,” as he called them, discouraged hundreds of drivers out of the business. But 800 drivers were still holding on.

What began as an LA phenomenon spread to San Francisco and San Diego, and across the nation. Within a year, over 62,000 jitneys were operating in 175 cities.

All contemporary accounts anticipated that jitney transit would become a significant new business. But the bubble soon burst, in part because of increased regulations. City governments grew concerned that the jitneys would bankrupt their mass transit systems, as had happened in Atlantic City. The city took action to ensure that streetcars survived and continued serving areas of the city that weren’t profitable for jitney business. Also, they wanted to protect their revenues from transit companies.

Cities began imposing restrictions like those Los Angeles considered: licenses, insurance, strict regulation of routes. Some cities prohibited jitneys from using the same streets as trolley cars. Or they prohibited drivers’ deviating from a single, approved route. Some cities required the jitney drivers to remain on duty for 12 to 16 hours each day. And some city governments began subsidizing mass transit to help it compete.

Consequently, within three years, 90 percent of American jitneys had gone back to being the family car.

It’s still too soon to tell if Uber will escape the fate of the jitneys. Uber enjoys the advantage of being a highly capitalized corporation. The jitneys never had an organization to fight city hall. Uber can also claim it is creating jobs. Passengers like its ease and economy as much as they hate the prospect of hailing cabs that seem inexplicably scarce.

It seems unlikely, in today’s political atmosphere, that government regulation has much chance of reigning in a booming business. However, it’s not impossible that a state or city ordinance could impose restrictions and fees on Uber drivers that would make using their personal vehicles less profitable. There’s a possibility that a significant rise in employment —however unlikely that might be—would lure Uber’s independent drivers toward more lucrative jobs. Likewise, passengers may come to dislike being rated by their drivers, or the practice of surge pricing, which boosts fares during busy hours.

Given the momentum Uber has, it is unlikely the company will follow the jitneys into obscurity. But then, the jitneys appeared unstoppable 100 years ago.