North Country Girl: Chapter 27 — Broomball and Other Activities

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

On weekend nights, kids meandered from one car to the other at London Inn, asking each other “Where’s the party?” All too often parents selfishly refused to leave home, or a drunken debacle the weekend before had resulted in Wendi Carlson’s mother forbidding her to have friends over, or Mr. and Mrs. Anderson were waging a minor, and ultimately unsuccessful, offensive to take back their basement from East High’s sophomore class.

So my gang of girls ended up doing a lot of drinking al fresco, even when the snow piled four feet high and the temperature dropped to zero. I staved off the cold in long underwear and my toasty army surplus green parka with a neon orange lining, the hood trimmed with fur from some strange beast, the exact same jacket worn by all my friends; when we gathered outside to party, we looked like some weird winter drinking team.

The multiple layers we wore underneath that parka kept us warm, but also made peeing a two-girlfriend job, one to hold you up so you wouldn’t fall bare-assed into the snow and one to block the view from curious teen boys, as the process took a while. You had to unzip and then shove down the three layers of jeans, long underwear, and panties past your knees, before you could grasp the arms of Friend Number One, lean back till your butt was almost touching the snow, and finally feel that hot blissful stream that you hoped missed your boots.

Drunken tobogganing on the hilly ninth hole of Northland Country Club was a favorite winter activity until Andie James knocked out her upper incisors when she shot head first off the sled and we had to deliver her bloody-mouthed and smashed on Tango Orange Flavored Vodka to her distraught parents.

We then took up drunken broomball, the only team sport I have ever enjoyed. The first half of drunken broomball was collecting brooms. We drove up and down the dark snowy streets of Duluth, peering at each porch and stoop illuminated under a circle of pale light til we spotted one that had a simple, regulation, round-handed, yellow-bristled wooden broom leaning against the house, kept there to sweep fresh snow off the steps. Wendi Carlson — no one else was brave enough — leapt out of her well-earned shotgun seat, ran close to the ground in a Groucho Marx crouch to the target house, snatched up the broom, ran back to the car, threw the broom inside, trying not to whack anyone, and hopped in while we all yelled “Go go go!” and the White Delight peeled out.

When we had gathered the same number of brooms as girls, we drove down to the Congdon Elementary ice rink, lovingly created and maintained by Mr. Swan, the scary janitor, every winter. The rink was totally deserted at night, faintly lit by the street lamps and stars. We stuck bottles of Night Train and Tango and Mad Dog and occasionally an actual real bottle of Southern Comfort in a rink-side snowbank and grabbed up our brooms. We slipped and slid skatelessly around the ice, laughing hysterically, falling on our asses, and occasionally swatting a volleyball in the direction of a hockey net. There were many breaks for drinking and helping each other pee. It was always hard for me to remember which net my team was supposed to be aiming at, but I rarely touched broom to ball anyway. I was there for the girls, for the drunkenness, for the laughter. We didn’t keep score; it was like the caucus race in Alice in Wonderland. Suddenly the game would be over and we would head back to the London Inn, thoughtlessly leaving both bottles and brooms scattered on the ice for Mr. Swan to clean up the next morning.

Once the snow was off the ground and the temperature reached a balmy fifty degrees, new drinking venues opened up. Former Girl Scouts and YWCA campers, we built raging bonfires on the lakefront, which attracted boys from miles around, and which I hope we properly extinguished. There was also the abandoned one-room Lakeside train depot, which offered shelter even if it had a faint whiff of hobo piss. This was a popular spot as it was where the trains slowed down before entering the yard. A test of manhood (or drunkenness) was to run alongside the train, jump and pull yourself up the ladder, and ride a few hundred feet down the line before launching yourself off into the cinders that bordered the rails.

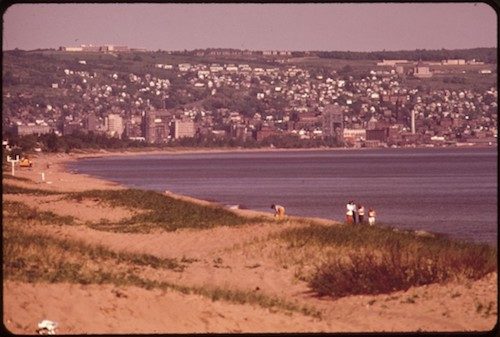

Finally, it was Duluth summer, when we would shiver in our bikinis at Park Point beach trying desperately to get a hint of a tan, playing Spades, listening to WEBC on the radio, singing along to “My Cherie Amour” every time it came on, which was twenty times an afternoon, gossiping about boys, and smoking (except me). There were trips out to rustic lake cabins, with smelly outhouses and rooms lit by kerosene lamps, and hopefully, parents back in the bustling city of Duluth, so we could carouse freely, long into the twilight evening, the sun still beaming off the lake water at ten at night. If we were lucky or if someone had dropped a hint, groups of boys discovered our location and arrived by the carload, bearing more bottles of booze and sleeping bags to cuddle and steal kisses in.

With all those other pleasurable activities, enjoyed in the company of my solid band of girlfriends, every week I crossed my fingers and wished that Doug Figge would have to spend both Friday and Saturday nights over the Fryolater. I liked the idea of a boyfriend much more than the boy himself.

***

Before the end of my sophomore year, I received a letter from Global Citizenship, inviting me back for another session of junior international diplomacy. Most of my girlfriends had landed summer jobs; at 15 I was too young for anything but babysitting, which I despised. I had a lot of summer days to fill, so I signed up for another go at becoming a Global Citizen, deciding that the hours spent lost in the black and white visions of Fellini and Bergman more than made up for the tedium of running imaginary countries.

The letter also informed me that this year’s Global Citizenship class would count toward high school graduation credits. Doug Figge listened to my ramblings about last summer’s course — the fabulous movies, the atomic bomb attacks — with half an ear, as he was busy trying to wriggle his hand inside my pants, but he took notice when I mentioned the credit. The next day I found out that Doug, John Bean, and Joe Sloan had all signed up for Global Citizenship.

Joe Sloan had come back from his strict boarding school with a serious hallucinogen habit, which he immediately passed on to Doug and John. Since I was unable to smoke a joint I was never offered so much as half a tab of acid. When not working or at Global Citizenship, the three boys, with me in tow (Mary Ann Stuart was MIA that summer), got high in Joe Sloan’s basement, blasting Cream and looking at the walls. There is no worse hell than being stuck in a room for hours with people who are tripping so hard they forget to turn the record over.

That summer’s Global Citizenship class was a bust. There were the two bright young men from last year, now even more hopeful that all the made-up nations and the kids running them could learn to live in peaceful harmony. The nuclear option had been removed from the game, making it even more tedious and probably closer to what the real UN is like. And instead of those wonderful foreign films, there was Photography. We were broken into groups of four or five, given one (1) camera per group, and ordered to create a slide show depicting a social issue. I don’t know what kind of Dorothea Lange images these young men expected in prosperous Duluth; what they got were mostly photos of the town’s three most prominent winos and a few liquor store Indians.

I was stuck with Doug and John and Joe, who decided our group’s topic would be drugs. I was not given a vote; in fact, I never even got to touch the camera. The boys completed our assignment without ever having to leave Joe Sloan’s basement. They took photos of album covers.

That was our slide show on a social issue: drug-inspired album covers — “Tommy,” “Their Satanic Majesties Request,” (with that weird wavy plastic insert), and “Court of the Crimson King” — one slide clicking into focus after the other, with “Crystal Ship” by the Doors as the soundtrack. After the lights went back on, the two nice young men shook their heads, expressed their disappointment in our group, and told us we would not receive credit for the class. One of the teachers pulled me to the side later to ask, “Are you okay? Are those boys giving you drugs?” If only.

My mother was also taking a class that summer at the university, having decided to resume her college education, which had been interrupted by my conception and birth. Three afternoons a week I had the ultimate teenage luxury: a parentless house. All my girlfriends who were off work came over to sit around the kitchen table, fog up the breakfast nook with cigarette smoke, and make plans for that night (“We’ll meet at the London Inn”). If my sisters were also out of the house, I’d be with Doug on the living room couch, him splayed on top of me, tentacled like an octopus, hands everywhere, oily-faced and hot-breathed.

Why didn’t I just break up with him? Why did I allow him to maul my tiny bosoms when it gave me no pleasure at all? Why did I give in to Doug’s pleas to “Just touch it, just put your fingers on it?” so he could have the spurt of pleasure while all I got was a sticky hand?

I kept hoping that somehow Doug would magically disappear and Joe Sloan would finally realize that we were meant for each other. Or that someone would say, “Here, Gay, here’s a tab of acid,” and make my time with Doug more interesting.

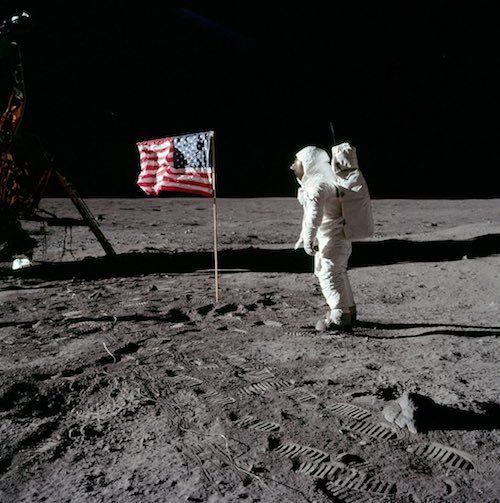

What I got was Doug’s needy grindings of his crotch on my hip bones, his crappy kissing, and his claim of “I love you,” supposedly the magic words that would make it okay to have sex with him. All of which wore me down and wore me down until I finally succumbed on July 20.

Joe Sloan and John Bean were busy in Joe’s basement. Joe had just received a mail order kit to make fireworks, and he and John, pupils the size of pinholes, were cackling uncontrollably as they spilled gunpowder about a small work room. I don’t know if they were making bottle rockets or M-80s; I did know that I did not want to be around in case someone lit a cigarette. So when Doug stuck his tongue in my ear and drew me away up the stairs, I did not object. We crept up the back stairs to a long forgotten room, maybe a former maid’s quarter, with a small window angled under a gable, a single mattress, and a black and white TV on a dresser.

Doug, true to his upbringing, could not resist turning on the television.

“Look!” I cried. “It’s the moon landing!” Doug looked and then fell on top of me, yanking away my tee shirt and shorts. Oh the hell with it, I thought, let’s just get this over. Doug thrust his way inside me while I pretended it didn’t hurt. I turned my head towards the TV and watched Neil Armstrong take his first step on the moon while I said goodbye to my virginity. One small but necessary step for womankind.

For years I had been dying to have sex; I expected the transcendent experience described in my favorite dirty books, not one where my most vivid memory is of an astronaut. Years later, I still felt queasy every time I saw MTV’s logo of a man planting the flag on the moon.

There was no rubber; Doug had never offered to get one, and I had no idea of how to bring up the subject. I took the idea that I could get pregnant from this awkward coupling and stuck in somewhere in my brain where I wouldn’t see it.

When it was finally over, Doug looked at his watch, but not to time his performance. “I have to get to work,” he said, and pulled on his pants. I did not look back to see what bodily fluids we had left on that lonely bed. Doug drove me home, and I called Wendi Carlson and complained. She assured me that every girl’s first time was awful, and that even though I was sore and still finding drops of blood in my panties, if I wanted to eventually enjoy it, I should keep on having sex with Doug.

North Country Girl: Chapter 22 — Gay’s First Date

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

I spent most of ninth grade imagining myself flitting about Haight-Ashbury, swinging my love beads and my perfect, shiny, Michelle Phillips hair, ingesting an interesting variety of drugs, and being fawned over by boys who looked like Mick Jagger or Jim Morrison. But my sad reality was that I was a plain girl with glasses, wearing clothes picked out by my mother, a girl who had never even sipped a beer or smoked a cigarette.

The swinging 60s, the youth revolt, consciousness-raising, be-ins and sit-ins and rap sessions were all happening very far away. Duluth was still country clubs, bridge parties, scary greasers from the West End with pomaded hair, black leather jackets, and white tees, useless home ec lessons, Sunday church dresses, dads driving while drinking a can of Grain Belt beer and then chucking the empty to the side of the road. We were so far out of the mainstream we hadn’t even gotten the Keep America Beautiful message.

No Duluth tradition was as firmly welded into the past as Cotillion. Every year, twenty fourteen-year-old boys and twenty fourteen-year-old girls were invited to take part in Cotillion, or in plain English, ballroom dancing lessons. This was a privilege reserved for kids from “better” families: we were the sons and daughters of doctors, lawyers, businessmen, who lived in the big houses in the prestigious neighborhoods. Never mind that the rest of the country was doing the frug, the pony, and the monkey. We chosen few were learning to fox trot.

Cotillion was held Thursday nights, from seven to nine on the second floor of Northland Country Club, and if that was a ballroom I’m the Queen of Spain. A long bench ran along all four sides of a drab, drafty room, half occupied with sweating, dweeby boys in ill-fitting jackets and strangling neckties, and half by anxious, overdressed girls. Girls were required to wear white gloves, god forbid our hands should touch sweaty boy hands. Dancing was taught and decorum maintained by two elderly, overweight matrons, who had been annoying the golden youth of Duluth for years untold.

For most of the dragging hours, the boys asked the girls to dance. Who knows what was worst: waiting, waiting, waiting, until I was the only girl still sitting on the bench and short, pimply Tom Gunderson, after examining the ceiling and the floor, just in case there was another girl hiding there, grudgingly asked me to dance; or on the rare occasion, when the planets aligned, of a girl asking a boy dance, when I had to decide how high to aim and how quick to move. A boy couldn’t turn me down, but he could make a face letting me know that he was hoping any other girl would have gotten to him before I did.

I hated Cotillion. It reinforced my lowly standing in the ninth grade boy-girl Olympics: only if a spelling bee broke out would I ever be any boy’s first choice. And it was impossible for me to learn to fox trot or cha cha or waltz, being literally unable to tell my right foot from my left. My unlucky partner and I would be shoved to the side of the room by one of the dance mistresses, who would then loom over me, glaring at my feet and shouting “ONE AND TWO AND CHA CHA CHA.”

My mother was thrilled to supply dress after dress for Cotillion; but it didn’t matter how cute my dress was; no boy cared about a dress. This was a lesson I was unable to get through my head; at the ninth grade graduation party my adorable Dr. Zhivago-inspired dress and fancy beauty shop up sweep failed to entice a single boy to ask me to dance.

Cotillion did teach me how to keep my tears of embarrassment and shame damned up those nights when the boy-girl numbers did not match and I was left alone on the bench, dance after dance, until some unfortunate boy was forced to come over and offer me a sweaty palm. I learned that when it’s whispered through the ballroom that Martin Luther King was assassinated, and the dance mistress is still clapping her hands and telling the boys to hurry and pick out their partners, that something is severely screwed-up.

After being chosen last at every Cotillion and left holding up the wall at the ninth grade graduation dance (I finally retreated to the girls’ bathroom where I had a good cry and then washed my face so my mom wouldn’t know that her choice of dress and hair do had not worked a miracle) I was convinced that I would never have a boyfriend.

Then one warmish June day, right before the end of school, I received two gentleman callers. My mother, down to one of her last nerves, had thrown all three of us girls out of the house. Heidi and Lani had gone off in search of other kids; I was slumped on the front steps engaged in my favorite outdoor activity, reading a book, when down Lakeview Avenue lumbered two gangly teenage boys, looking, shockingly, for me. It was Joe Sloan and Wesley Baggot.

Wesley was in ninth grade at Woodland, though not in any of my classes, and definitely not a member of Cotillion, having the longish hair and scruffiness of a would-be greaser. He was cute enough, though, and he was a boy. I had never spoken to Joe Sloan, who was taller with longer hair, and an air of mystery. The Sloans, a family of seven or eight children, lived in an immense robber baron mansion, a house with an unknowable number of rooms built of ominous black stone blocks, complete with gatehouse and a quarter-mile of winding driveway, set back on acres of dark piney woods. I had been delivered several times to this house to play with a girl my age, Jane Sloan, a musical prodigy who eventually went off to boarding school. I don’t remember if we played Barbies or board games or hide and seek in that huge house, my memory is stuck on the concert grand piano, ebony black and the size of a car, smack in the middle of a living room as big as a tennis court, and on the industrial-size chrome milk dispenser in their kitchen: you’d lift the heavy lever and milk would run from a clear tube into your glass. I also remember glimpses of Jane’s brother Joe, who had a reputation for borderline juvenile delinquency, and who attended not a fancy pants boarding school, but one intended to correct the waywardness of rich boys.

Of my two suitors, of course I preferred Joe Sloan, especially because when they stopped at my front sidewalk, he lit a cigarette. I managed to not hyperventilate and to actually make small talk with two boys, discussing the merits of East High, where I was going, and whose students were regarded by all other Duluth teens as Cake Eaters, and Central, the other side of the track school, whose sports teams regularly thumped East, and where Wesley was headed. Joe did not comment on his school, but lit another cigarette and said he had to go. Joe and Wesley gave me a “See ya,” ambled off, and I rushed back into the house to call Cindy Moreland and tell her that I had just talked to two boys, one of whom was a year older and really, really cute, then spent the rest of the day imagine Joe reaching for me and sweeping me up in a passionate kiss that tasted like Lucky Strikes.

It took a few more visits from the two boys before the semi-awful truth came out: I was not the object of Joe’s desire. It was Wesley Baggot who asked me out on my first date. I can count on the fingers of one hand how often a boy has asked me to the movies, so every moment of that event is etched into my brain.

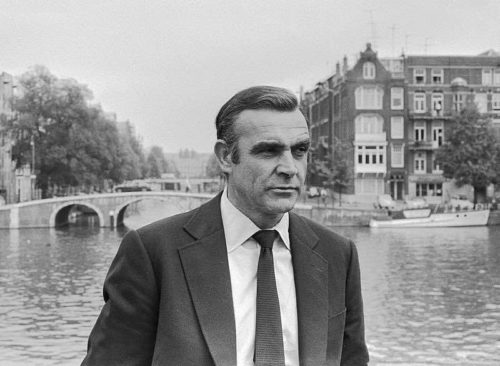

What I wore: black elephant bells of thin-wale corduroy with a pink and green rosebud print. I wish I still had those pants. The bell bottoms were so wide, Wesley Baggot asked if I were wearing two skirts. We went to a James Bond double feature, Dr. No and Goldfinger, very racy stuff for fourteen-year-old me. At some point after the appearance of Odd Job, Wesley’s hand crawled over the arm of the seat to search for mine. Caught in his death grip, I proceeded to lose all feeling in my right hand. I tried to ignore the pins and needles shooting up my arm and the intense embarrassment of watching Pussy Galore and James Bond going at it in on the big screen in Technicolor so I could memorize every detail of my first date, which I poured out to Cindy Moreland the next day, as we wrapped album covers in tin foil to use as reflectors and basted ourselves in baby oil in an attempt to woo a California tan from the pale Minnesota sun.

She sympathized with me over losing out on Joe Sloan, but a boy was a boy. Wesley

Baggot had paid for my ticket, bought me buttered popcorn and a waxy cup of Coca-Cola, and that was an official date. The next step in the Duluth dating ritual was dinner at Somebody’s Place, a small teen-friendly restaurant where no liquor was served; you washed down your choice of thirty-six different hamburgers (ranging from the Italian with red sauce and mozzarella to the “sundae burger” with chocolate syrup and whipped cream) with Swamp Water (a mixture of coke, root beer, and 7-Up), or a pretentious pot of orange and cinnamon Constant Comment tea.

I spent hours waiting for the phone to ring or for Joe and Wesley to show up again on my front lawn, hours in front of the bathroom mirror, applying a pale pink Yardley Slicker to my lips then attempting a sexy Honor Blackman pout, taking my glasses off, thinking I couldn’t read the Somebody’s House menu without them, putting them back on, realizing that I knew all twenty-eight hamburgers by heart, taking them off again, peering under my lashes trying to see what I looked like when I closed my eyes and puckered up for a kiss…all in vain. Joe Sloan and Wesley Baggot had vanished. The phone continued to not ring and I descended into the horrors of the teen girl mope.