Heroes of Vietnam: Bob Hope—The GI’s Best Friend

This article and other features about America in Vietnam can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Heroes of Vietnam. This edition can be ordered here.

This article and other features about America in Vietnam can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Heroes of Vietnam. This edition can be ordered here.

—Originally published March 12, 1966

The band played “Thanks for the Memory,” and he sauntered onstage — a stocky, brown-eyed man wearing an orange shirt, black dancing slippers, and the green beret of the U.S. Army’s Special Forces. In one hand he held a golf club. For a few seconds he stood there, unsmiling, and surveyed the audience. Then a shark-like grin began to spread across his face.

“I’ve never seen such happy servicemen,” he said, “and why not? This is the only country in the world where the women come out to meet you in pajamas.”

Overhead, like aerial scorpions, armed helicopters circled the camp. Out on the perimeter, 1,000 yards away, infantrymen crouched behind machine guns and scanned the clumps of elephant grass for a sight of the Viet Cong. Up on the stage, comedian Bob Hope was delivering his rapid-fire monologue — and bringing laughter to thousands of U.S. servicemen who hadn’t had anything to laugh about in a long time.

In 12 days last December, Hope and his troupe of entertainers traveled 23,000 miles to visit four hospitals and put on 24 shows for U.S. military personnel in Thailand, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Guam. As the war in Vietnam has escalated, other entertainers have traveled overseas to lift servicemen’s morale. For many of them, it was a new experience. For Hope, it was almost routine.

Twenty-five years ago this month, at March Field, California, the seemingly indefatigable comedian staged his first show exclusively for servicemen. Since then, under the joint sponsorship of the USO (which was celebrating its 25th birthday that year) and the Defense Department, he has flown more than 2 million miles to entertain 11 million soldiers, sailors, marines, and airmen. In the process he has become a sort of jet-propelled national institution. To these servicemen, as columnist Irv Kupcinet once pointed out, “He’s Uncle Sam, Santa Claus, and a letter from home all wrapped up in one neat package of hilarity.”

Though Hope is pushing 63, there is an ageless quality about the man — many of the servicemen applauding his performances today are the sons of GIs he once entertained in places with names like Palermo, Tarawa, and New Caledonia.

One morning, just before Christmas last year, I joined the troupe in the cabin of a U.S. Air Force C-141 as it streaked at 27,000 feet toward Saigon. In the past four days, the comedian had staged five full-length shows for U.S., Thai, and Australian servicemen at airbases in Thailand. But now, as the plane began its descent into Saigon, he seemed apprehensive. “This is where the trip really starts,” he said to singer Jack Jones. “If you want to be nervous, now is the time.”

Landing at Tân So’n Nhu’t Airport, the giant jet taxied to a halt, and the door was opened. Clutching a golf club, Hope stepped off the plane first, followed by a retinue of performers, including Anita Bryant, Diana Lynn Batts (Miss USA), Joey Heatherton, and Les Brown and 14 members of his “Band of Renown.”

“What’s the golf club for?” a reporter asked.

Hope grinned. “Well,” he said, “that’s just to keep my grip in shape until I get back, and also for a little protection.”

“From whom, Bob?”

“From both sides.”

“They blew up the Brink Hotel (an officers’ billet in Saigon) the last time you were here,” another newsman said. “Are you scared this time?”

“Not at all,” Hope replied. “In fact, I may even sleep on top of the bed.”

Like a master conductor leading an orchestra, Hope dominated the press conference. For more than 20 minutes, he parried questions with gags, not only because he seemed to believe that this was what the newsmen expected of him, but also because he seemed genuinely wary about expressing personal opinions.

“Bob doesn’t like to talk about his health, politics, religion, or his adopted children,” explained Jan King, a bubbly woman who serves as his “secretary for movies.” Nor does he like to talk about himself. Questioned on personal matters, he becomes fidgety and either changes the subject abruptly or turns and walks away.

Inside his dressing room behind a knock-down stage at Tân So’n Nhu’t Airport that afternoon, Hope put on his own makeup, then turned to review his cue cards. For the past few weeks, his seven writers had been concentrating on gags for this tour, and here — stacked on the floor of the dressing room — were the results of their efforts: 800 large, rectangular cards, each containing one or more jokes. The gags were broken down into such loose-knit categories as “traveling with pretty girls,” “remote bases,” “bad food,” and “excessive security.” As his chief cue-card assistant, an affable Irishman named Barney McNulty, flipped the boards, Hope decided that he would emphasize the security theme on this show. Up onstage, Les Brown’s musicians were playing “Fly Me to the Moon.” Hope was due to go on next. Grabbing his golf club, he waited in the wings to be introduced, and then strolled out to the microphone amid a burst of applause from 12,000 servicemen.

“I want to thank the provost marshal for the wonderful protection we’ve been getting,” the comedian declared. “They have 25 men with machine guns guarding the girls, and for the fellows, they have a midget with a slingshot. … No, security here is really sensational. I’ve been frisked so many times, I’m even beginning to like it.”

At every punch line he lowered his jaw, and his face took on an expression of feigned anguish. The mannerism never failed to provoke laughter.

The show continued for more than two hours, and Hope was onstage constantly — both as a performer and as master of ceremonies. The crowd roared when Hope brought Carroll Baker onstage.

“That’s a nice gown you’ve got,” the comedian began. “Is it a Schiaparelli?”

“Oh, I’m sorry, Bob,” Miss Baker replied. “I’ve forgotten where I bought it.”

“Well, can I check the label?” With a knowing wink at the audience, Hope stepped behind her and pretended to examine the manufacturer’s tag. “What does it say, Bob?”

“Off limits,” Hope replied.

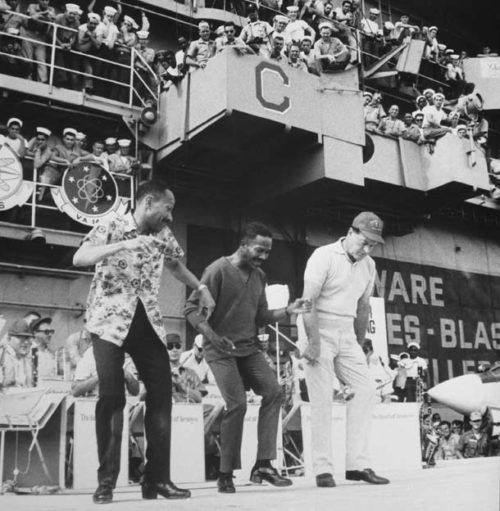

He kept up the comedy routine for another 10 minutes, danced a soft-shoe number called “Will You Still Be Mine?” with Miss Baker, and then took a break as actor Peter Leeds stepped forward to tell a few gags about U.S. television commercials. But soon Hope returned to the microphone to introduce Joey Heatherton, a 21-year-old blonde who burst onstage wearing a black-sequined leotard and waving a feathery white boa. A grin spread across his face as he sat in the wings and watched her stomp through a wild Watusi with volunteers from the audience. “What a kid!” he said. “Isn’t she great?”

Ten minutes later, Hope was back onstage for a final production number with the entire cast, and then, as the show closed, he asked Anita Bryant to sing “Silent Night.” It was Christmas Eve, and many of the servicemen had tears in their eyes.

After the finale, Gen. W.C. Westmoreland, chief of the U.S. Military Assistance Command in Vietnam, presented a plaque to each member of the troupe and called Hope “the best friend the serviceman ever had.” He went on to quote the comedian as having said, “I’ll stop going overseas only when they stop having Christmas.” The audience applauded resoundingly, and Hope seemed embarrassed. But now a limousine was waiting to speed him to a nearby military hospital. Followed by the rest of his troupe, Hope moved through the wards at a brisk pace. He asked each man how he got hurt and how he was feeling. He told a few jokes and signed autographs. But he never expressed any sympathy.

“That’s the last thing these guys want,” he says. “If you give them sympathy, they’ll turn away. You gotta be clinical about it and talk to ’em on an honest basis. All these guys in traction, I say, ‘Don’t get up, fellas,’ or ‘Okay, somebody get the dice and let’s get started.’ In the old days, [Jerry] Colonna and I would even get in bed with the patients.”

“You have to show them that you’re really happy to see them,” Colonna says, “and in some cases, it’s really tough. You know how they feel and they know how they feel. I choke up and get a lump in my throat and I have to walk away. But Bob — he’s learned how to hold back his emotions.”

He hasn’t always succeeded. Once, on the island of Espiritu Santo in 1944, Hope stopped by the bedside of a severely wounded soldier who was receiving blood transfusions. “I see where they’re giving you a little pick-me-up,” the comedian declared. “It’s only raspberry soda,” the boy replied, “but it feels pretty good.” Two hours later, Hope was told that the boy was dead. “I thought about how in his last moments he’d grinned and tried to say something light,” Hope recalls, “and I couldn’t stand it. I had to go outside and pull myself together.”

At nine o’clock next morning, three Chinook helicopters lifted the troupe from Tân So’n Nhu’t Airport to the First Infantry Division’s base at Di-An. It was very warm and the sky was clear, and because it was Christmas Day, a truce was in effect. Yet most of the 3,200 men in the audience were carrying weapons. Only a few hours ago, four GIs had been killed when their Jeep struck a mine just north of the base, and now an escort officer was saying that extensive security precautions had to be taken because the Viet Cong were known to be less than a mile away.

The temperature at the airbase that afternoon was a blistering 98 degrees, but the 7,000 servicemen in the audience didn’t seem to notice the heat. They roared their approval as Hope ridiculed the peace demonstrators on U.S. college campuses: “Our government’s got a new policy about burning draft cards,” he announced. “Now they say, ‘If he’s old enough to play with matches, draft him.’ … You’ve seen some of these guys with the shoulder-length hair. I guess they’d rather switch than fight.”

At 1:45 next afternoon, Hope was onstage again — this time at Cam Ranh Bay, a sandy supply depot on the Vietnamese coast 200 miles northeast of Saigon. “What is this,” he asked, “a rest-and-recreation area for camels? A supply depot for the Sahara?” The servicemen whistled and applauded.

A few minutes later helicopters whisked the troupe to the U.S.S. Ticonderoga five miles offshore. Hope had never put on a show from the deck of a carrier engaged in combat operations, and the prospect clearly excited him. After dinner with Admiral Ralph Cousins, he climbed up to the bridge to watch a squadron of F-8 Crusaders return from a mission over enemy territory.

By 2 p.m. the next day, all air operations had ceased and carpenters were driving the last nails into a makeshift stage on the flight deck. As the show began, Hope took a practice swing with his ever-present golf club. “I’ve played water holes before,” he began, “but this is ridiculous. … And it’s amazing what you can rent from Hertz these days. What a raft this is — it looks like Jackie Gleason’s surfboard.”

That same afternoon, the troupe flew to its second show of the day in Nha Trang. For security reasons, the Marines had not been told in advance when Hope would arrive. As he walked on the stage, a mammoth cheer erupted from the audience. Hope didn’t disappoint them.

“This is the most secret base I’ve ever visited. Everything’s strictly hush-hush. At dawn, the bugler just thinks reveille.”

As he left the stage, a sergeant cracked, “You look tired. Why don’t you send for the troops next Christmas?” Hope grinned, but when the show was over, he lay down on a wooden bench in the dressing room and, within two minutes, was fast asleep. But he didn’t have long to rest. There was another show to do that afternoon.

Click to Enlarge