Cover Collection: Farmers of the 1940s

In honor of National Farmer’s Day, we share some of our favorite illustrations of the people who worked the farms of America in the 1940s.

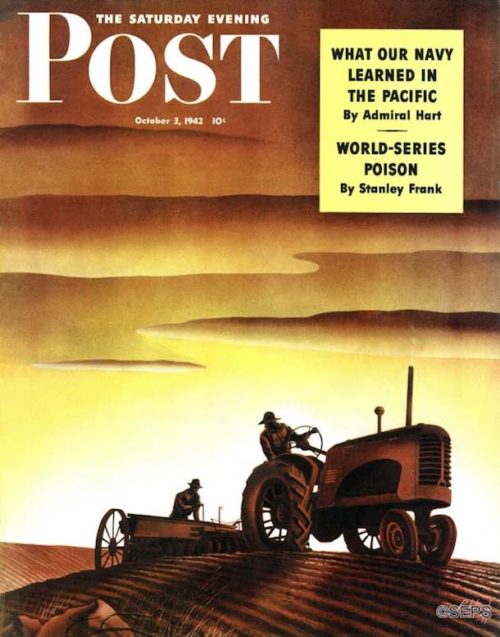

Arthur C. Radebaugh

October 3, 1942

In a year when many of the Post covers featured war-related images, this glowing, pastoral scene must have been a soothing one to readers. This painting reflects the regionalist style that was popularized by artists such as Thomas Hart Benton and Grant Wood. However, most of Radebaugh’s paintings were more futuristic; he created numerous illustrations for the airline and automotive industries.

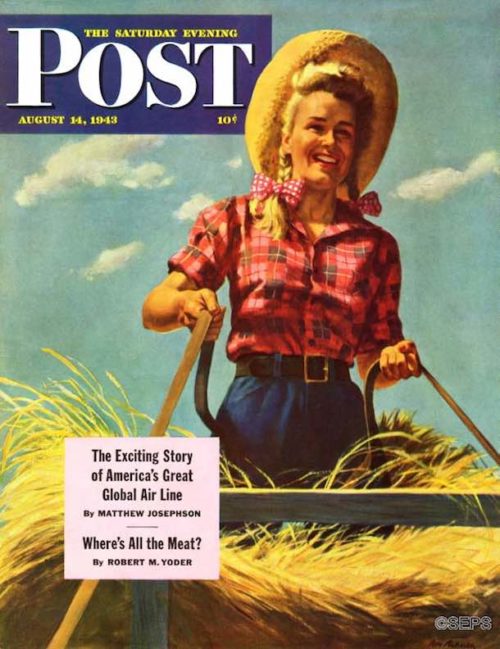

Ray Prohaska

August 14, 1943

Although he painted several interior illustrations for the Post, this was Ray Prohaska’s only cover. The woman atop the wagon with her straw hat, polka-dot hair ribbons, and plaid shirt is the quintessential farm girl. As with the previous cover, this happy scene gave readers a respite from the war.

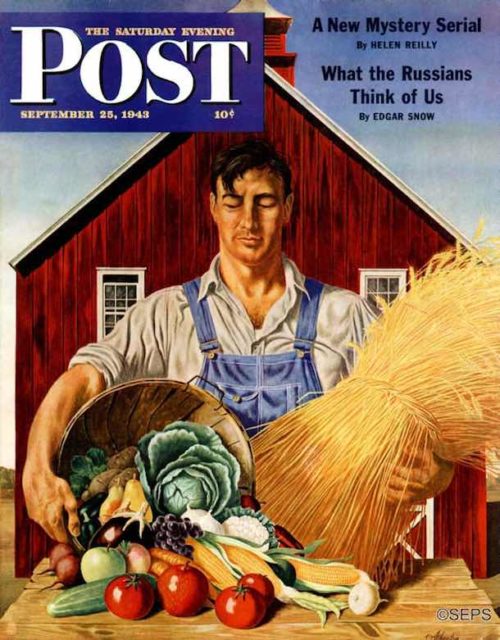

John Atherton

September 25, 1943

John Atherton painted 40 covers for the Post. Many were bold, architectural compositions of industry — steel mills, grain elevators, ore mines, and lumber yards. Atherton painted a number of more pastoral scenes, such as this farmer with his cornucopia of fruits, vegetables, and grains.

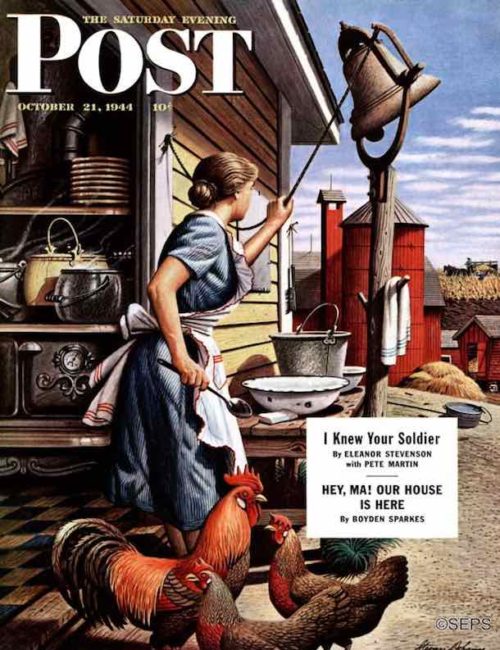

Steven Dohanos

October 21, 1944

Stevan Dohanos, inspired by Norman Rockwell’s talent, depicted everyday life in the 123 covers he created for the Post. Dohanos was also busy aiding the war effort by painting recruitment posters and wall murals for federal buildings. He also designed stamps for the federal government, starting during the Roosevelt administration, and staying in the profession the rest of his life.

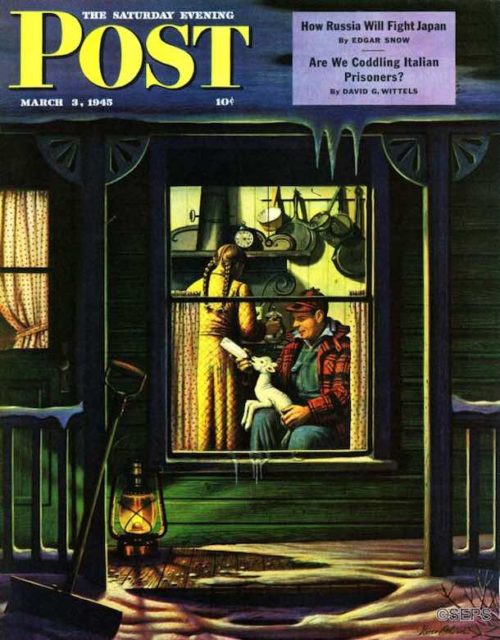

Stevan Dohanos

March 3, 1945

Stevan Dohanos made pencil studies of the lamb in this painting early in December on the farm of Raymond Platt, in Redding, Connecticut. Before he found his cover subject, however, he made a number of sketches in a drafty shed where lambs and ewes of all ages were quartered. “They stepped on my sketches and equipment; they pushed me all over the shed,” says Mr. Dohanos. “In fact, they acted just like people.”

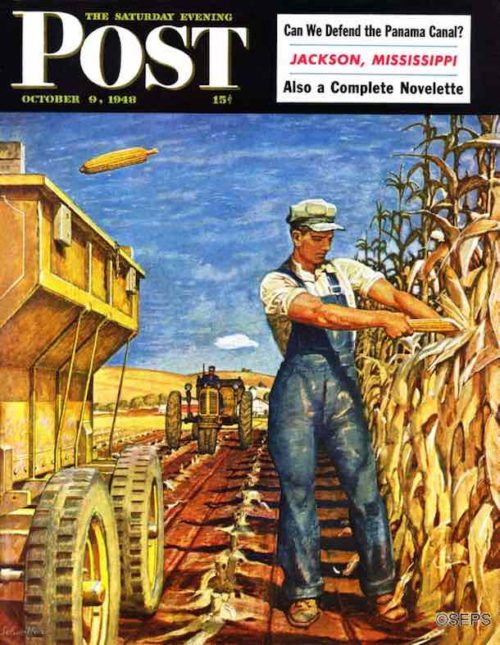

Mead Schaeffer

October 9, 1948

This Mead Schaeffer cover shows corn being picked by the “bang-board” method, which allowed a man to throw ears into the wagon without looking, because they would bang against a high board at the far side of the wagon and drop in. By 1948, most big farms used mechanical corn pickers, including the Lawton, Iowa, farm of Louis Peterson, the setting of this picture. The mechanical picker had already been used on much of the field, as the rows of stubble indicate, but the day Schaeffer was there, the machine was busy elsewhere. Farmer Peterson needed a little corn for his hogs. He got it the bang-board way—and Schaeffer got this cover.

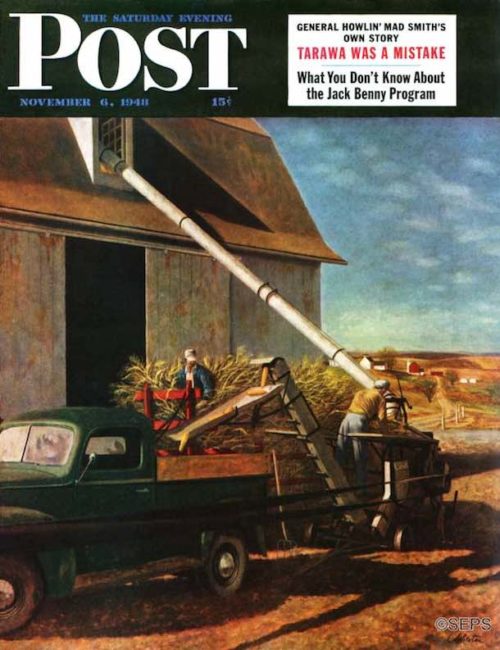

John Atherton

November 6, 1948

John Atherton’s cover painting depicts life on a farm near Madison, Wisconsin. The machine is a husker and shredder, which sends the husked ears of corn into the waiting truck, chops the stalk and blows the choppings into the mow, like hay. The power comes from a tractor offstage to the left.

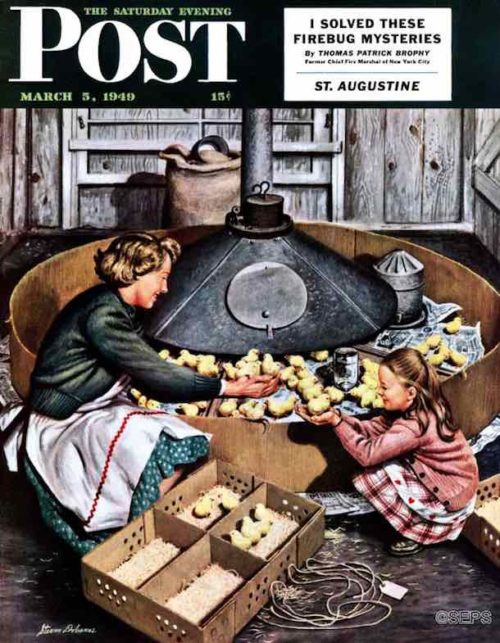

Stevan Dohanos

March 5, 1949

Stevan Dohanos felt apologetic about the request he made in a hatchery in Wallingford, Connecticut. “What I’d like to paint,” he said, “is baby chicks of one particular color. It’s a color people like to see on a bleak March day—a kind of pale lemon yellow.” It didn’t faze the hatchery men. “We’ve got about any shade you like,” they said, and began showing stock. The ones Dohanos chose—he thinks—were White Leghorns. The artist ended up pretty proud of his new knowledge. “That’s a coal-stove brooder,” he said professionally, “and technically correct. It has to be round. If it were square, you see, the chicks would get into the corners and crush themselves.”

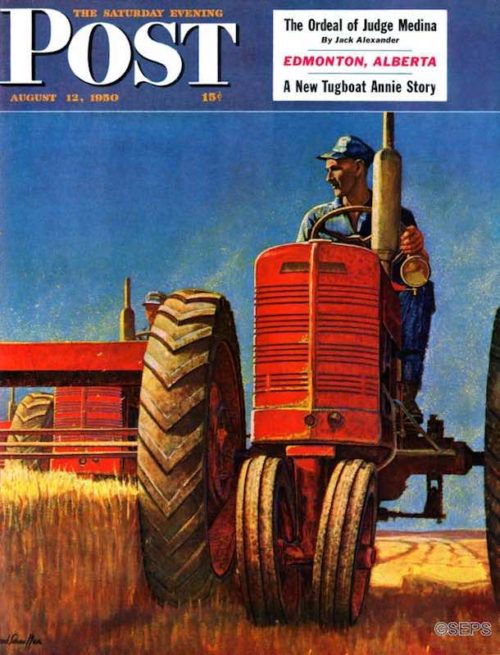

Mead Schaeffer

August 12, 1950

This cover is meant to coincide with the wheat harvest in the famous North Dakota-Minnesota Red River Valley. Artist Schaeffer, conditioned to small patches of Eastern wheat, was amazed by the endless golden seas of Midwestern grain. One day, in the fields, Schaeffer wondered where everybody’s lunch was coming from, and an airplane appeared, bringing same.

Cover Gallery: American Bridges

From San Francisco to Louisville to Pennsylvania, the beauty and grandeur of America’s bridges is on full display in these gorgeous covers.

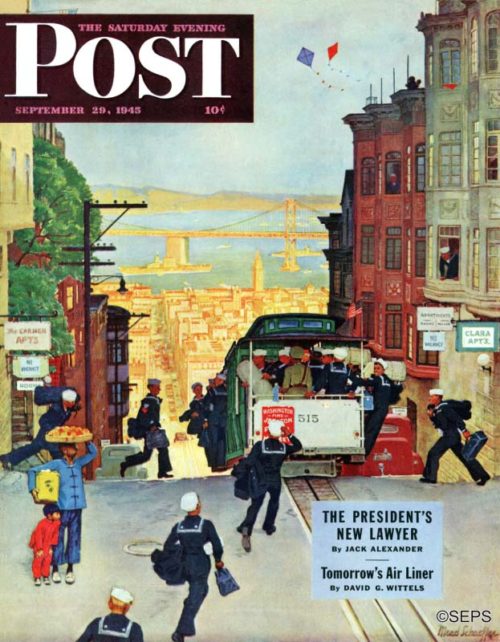

Mead Schaeffer

September 29, 1945

In August of 1945, the city of San Francisco announced plans to dismantle its famous cable car system. The Post was in the thick of the uproar that followed. Mead Schaeffer’s September 29 cover helped “touch off an explosive burst of civic pride” that ultimately saved the cars, as writer Elmont Waite recounts in this article published five months later.

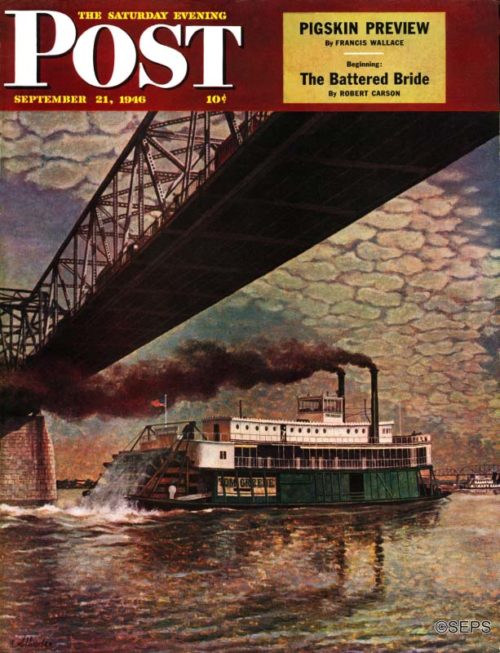

John Atherton

September 21, 1946

John Atherton painted his picture of the stern-wheeler at Louisville, Kentucky, where the Ohio rolls along on its way to join the Mississippi. Atherton enjoyed his stay in Louisville, but lost one of his illusions. A Vermonter, the artist went to Kentucky prepared to find that people there take things pretty easy. He had no sooner taken a preliminary squint at the river boat than a bustling Kentuckian took him in hand and arranged for the artist to work from a barge, which afforded a much better view. While relaxing at lunch, Atherton remarked that the job would take some little time, as he had to do a good deal of wandering up and down the river, in search of the proper site. A second energetic Kentuckian immediately put a car and driver at Atherton’s disposal, so the artist could cover more territory in less time. The motorized painter came back convinced that Kentucky is full of expediters.

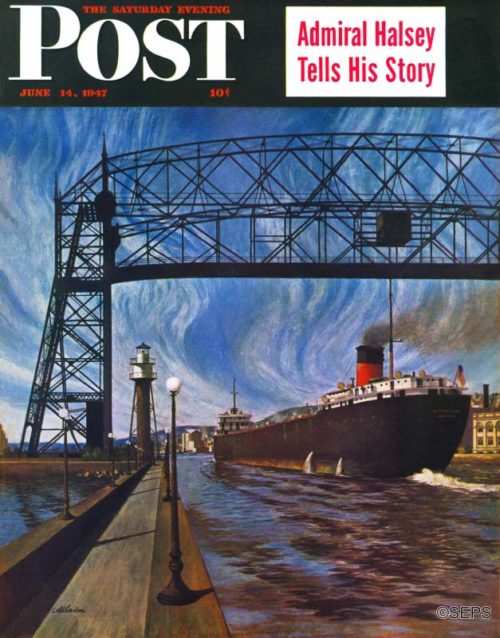

John Atherton

June 14, 1947

John Atherton’s cover painting is a continuation of our family album of American regions. This time he moved north, to the Paul Bunyan country, and thousands will not need to be told that the cover is a view of the husky city of Duluth. This is the ship canal, through which ore boats move out to begin their travels in the Great Lakes. The ore, of course, comes from the great Mesabi Range. Atherton chose a moment when the bridge had lifted to let one of the ore boats pass below. The trip to Duluth is one the artist had hoped for many years to make; he remembered being there as a boy of six, when he was deeply impressed. Not by Duluth’s Bunyanesque role in American industry, however, but with its excellent facilities for sledding.

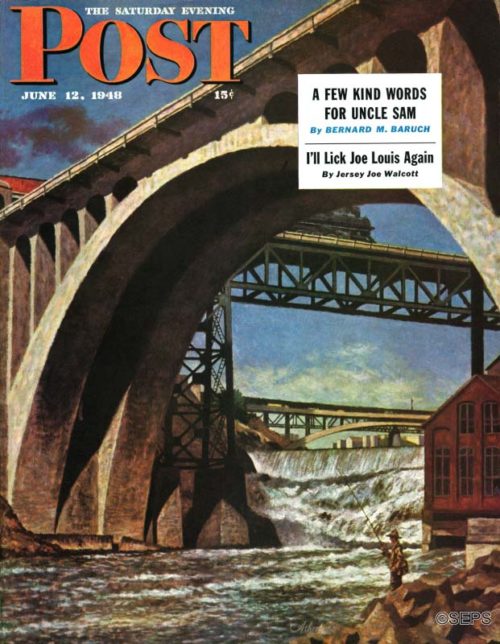

John Atherton

June 12, 1948

John Atherton’s cover painting is another page in our album of American localities; this time the scene is Spokane, and you are looking at the Monroe Street bridge, which is crossed overhead by a railroad bridge. Atherton lived in Spokane in his high-school days, and used to fish at the foot of these falls. In fact, when he needed a model for the fisherman, he dug out a photograph of himself at eighteen. It was the start of a lifelong devotion to fishing, not because Atherton himself had great luck in this river, but because he watched others haul out beautiful fish there—one rainbow trout that weighed nearly ten pounds. Atherton’s grandfather was an early settler and built a flour mill at the falls—the first in that region, Atherton believes.

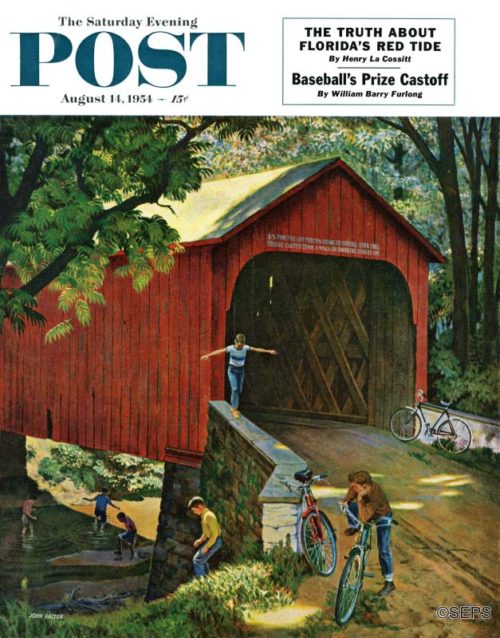

John Falter

August 14, 1954

A lazy summer day, a covered bridge, a crick or creek to play with, and a snake—how can one better define bliss? John Falter painted that bridge from life; its warning of “$5 fine for… smoking segars on” is an old rural Pennsylvaniaism, not a sample of the way the artist himself organizes words.

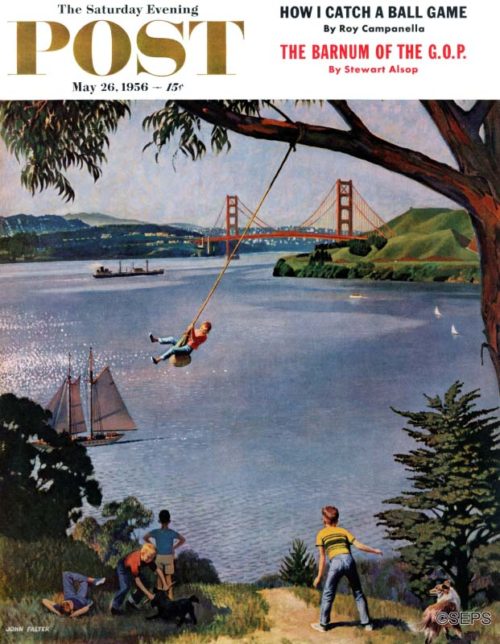

John Falter

May 26, 1956

When John Falter was strolling along Belvedere Island, admiring the grace of Golden Gate Bridge across the azure bay, he happily discovered that kids still relaxed in the mellow old hair-raising way. Falter’s cliffside home was two blocks to the right of his painting.

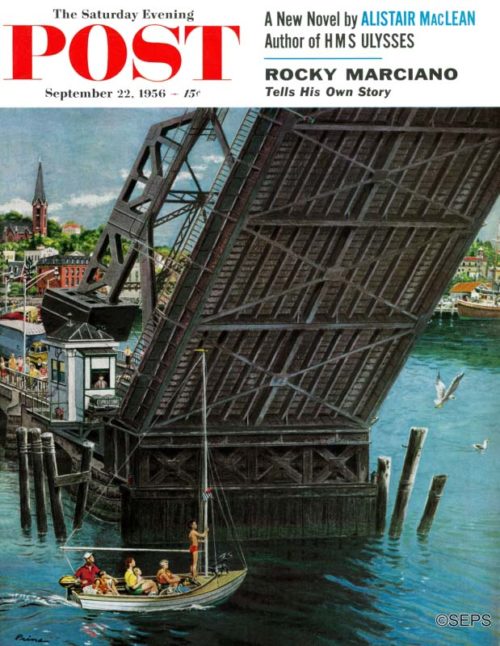

Ben Prins

September 22, 1956

Illustrator Ben Prins sat beside a drawbridge for three hours to watch it move, and it never moved a muscle, nothing wanting to go through but a gull. Finally, the kindly bridge tender, saying he’d better test the thing for shimmies anyway, waited till auto traffic was light and flapped it up and down for art’s sake. As no boats were visible, the motorists must have feared the man had gone on a bender.

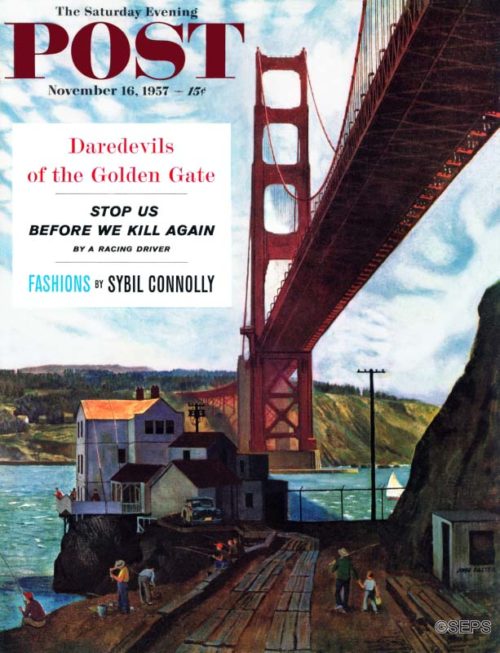

John Falter

November 16, 1957

To the left across the water: San Francisco, plus the New York Giants. The house is a lighthouse and the cables keep it from taking off for a sail someday. John Falter, who said he was something less than a superb sailor, had helped crew sailboats out through the Gate a few times, and usually had been delighted to regain dry land.

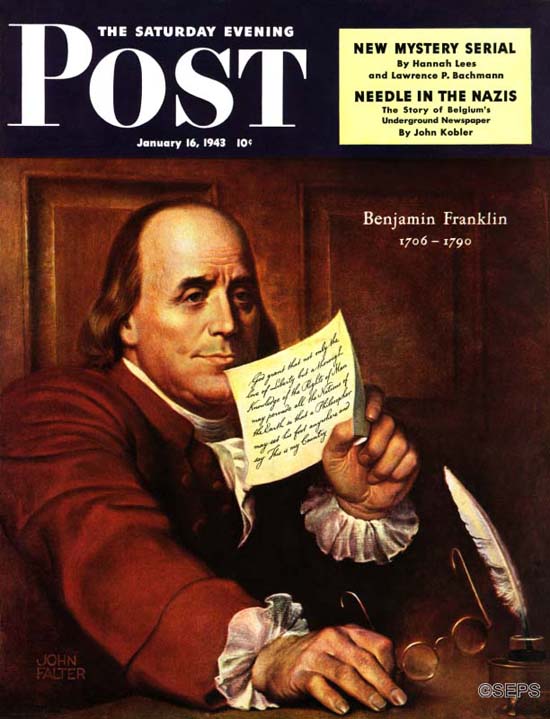

Cover Gallery: The Wisdom of Ben Franklin

Every January between 1943 and 1961, the Saturday Evening Post featured an image of Benjamin Franklin on its cover, along with a quote from the famed inventor, printer, and statesman. Below is a selection of those covers along with his wise words, which still resonate hundreds of years later.

John Falter

“God grant that not only the love of liberty but a thorough Knowledge of the Rights of Man may pervade all the Nations of the Earth so that a Philosopher may set his foot anywhere and say This is my Country.”

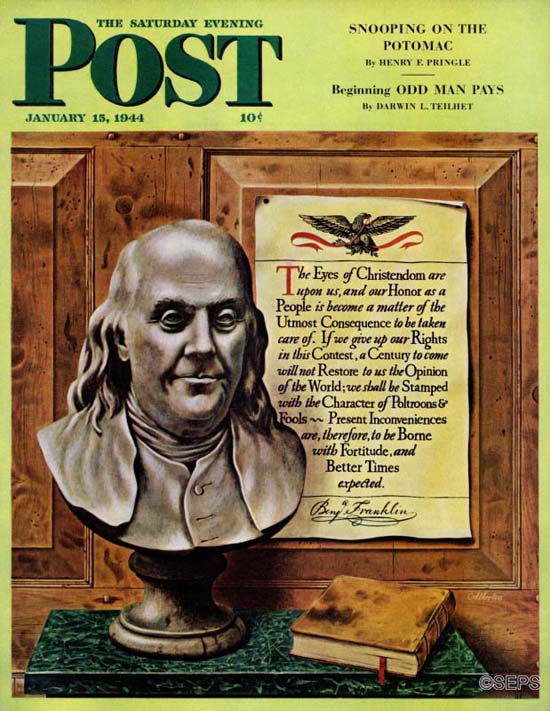

John Atherton

“The Eyes of Christendom are upon us, and our honor as a People has become a matter of Utmost Consequence to be taken care of. If we give up our Rights in this Contest, a Century to come will not Restore us to the Opinion of the World; we shall be stamped with the character of Poltroons & Fools — Present Inconveniences are, therefore, to be Borne with Fortitude, and Better Times expected.”

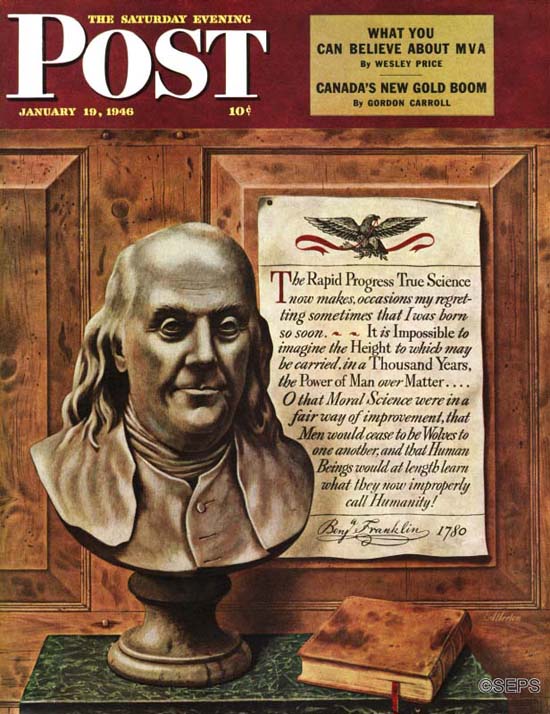

John Atherton

“The Rapid Progress True Science now makes, occasions my regretting sometimes that I was born so soon. It is Impossible to imagine the Height to which may be carried, in a Thousand Years, the Power of Man over Matter…O that Moral Science were in a fair way of improvement, that Men would cease to be Wolves to one another, and that Human Beings would at length learn what they now improperly call Humanity!”

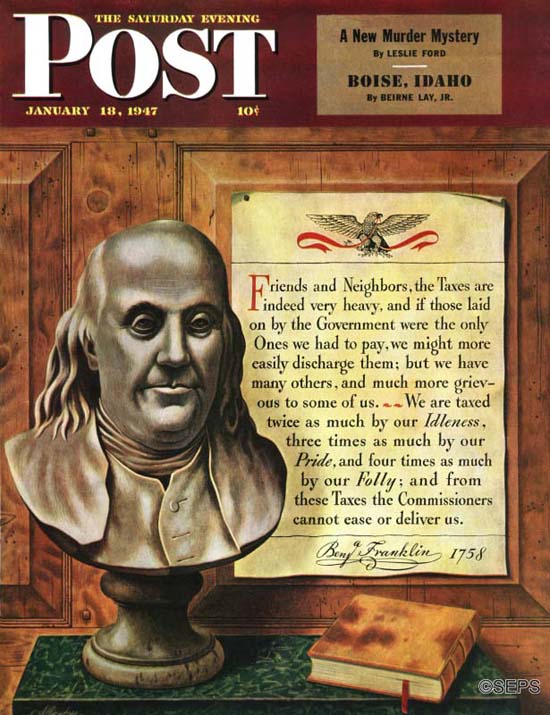

John Atherton

“Friends and Neighbors, the Taxes are indeed very heavy, if those laid on by Government were the only Ones we had to pay, we might more easily discharge them; but we have many others, and much more grievous to some of us. We are taxed twice as much by our Idleness, three times as much by our Pride, and four times as much by our Folly; and from these Taxes the Commissioners cannot ease or deliver us.

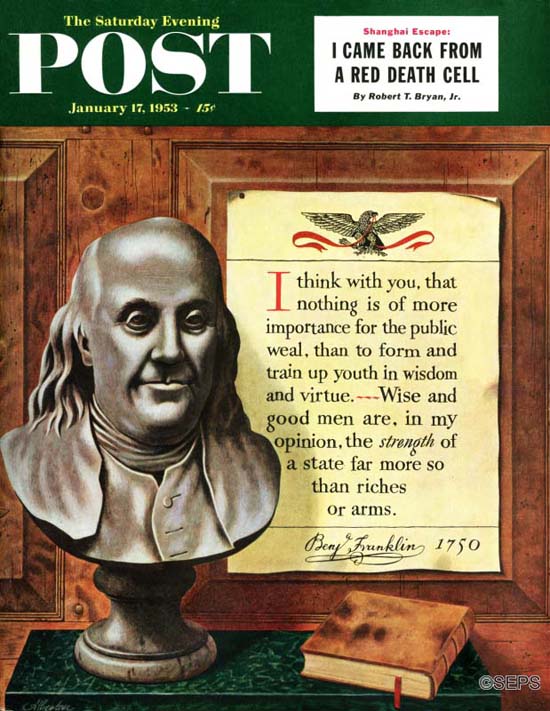

John Atherton

“I think with you, that nothing is of more importance for the public weal, than to form and train up youth in wisdom and virtue. Wise and good men are, in my opinion, the strength of a state for more so than riches or arms.”

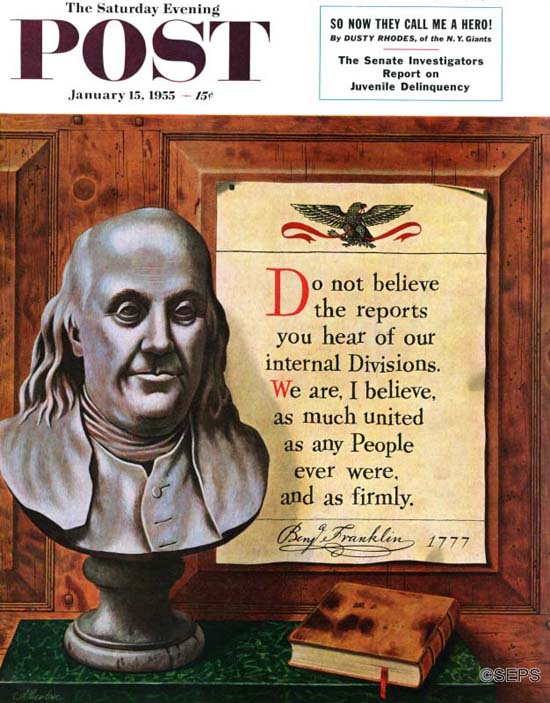

John Atherton

“Do not believe the reports you hear of our internal Divisions. We are, I believe, as much united as any People ever were, and as firmly.”

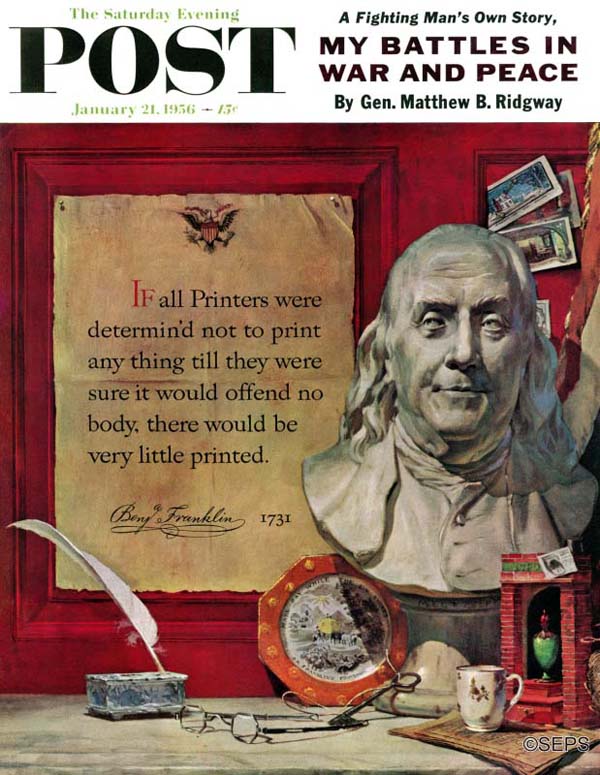

Stanley Meltzoff

“If all Printers were determin’d not to print any thing till they were sure it would offend no body, there would be very little printed.”

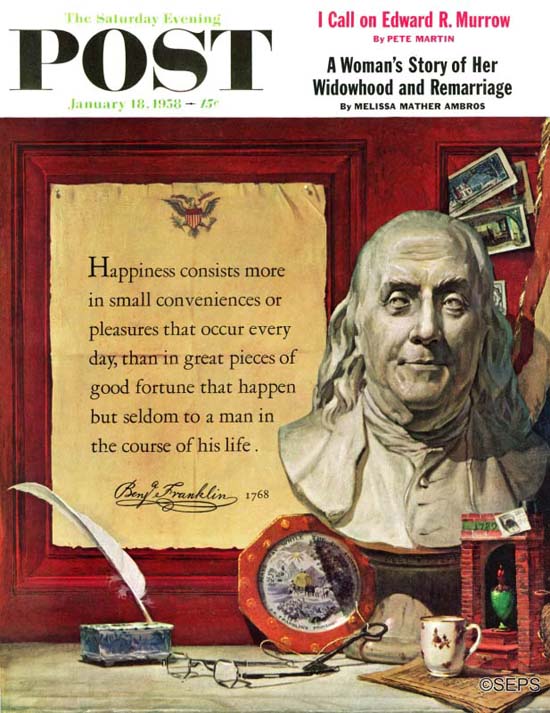

Stanley Meltzoff

“Happiness consists more in small conveniences or pleasures that occur every day, than in great pieces of good fortune that happen but seldom to a man in the course of his life.”

A Salute to Veterans

Tributes to the military have long been portrayed on covers of The Saturday Evening Post, from situations serious to humorous. In honor of Veterans Day, we would like to share some of our favorites.

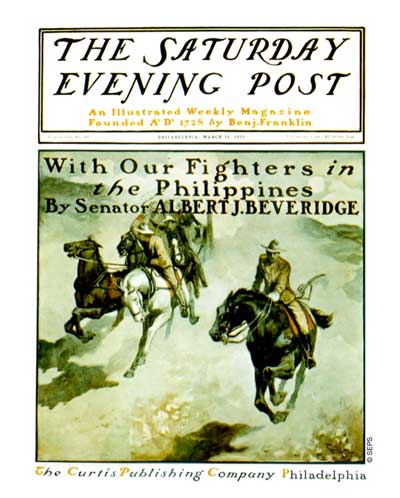

The first Post military cover? An action depiction of U.S. soldiers on horseback in the Philippines.

George Gibbs

March 31, 1900

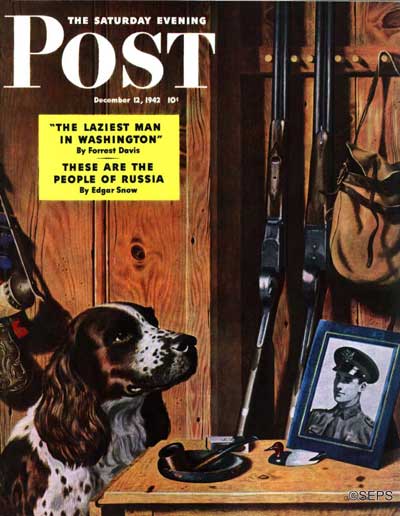

He’s in the Army now. A seldom seen cover from December 1942 by John Atherton shows a faithful dog and a photo. From the uniform, we can guess where its master is. We hope he returns home soon – Spot is itching to go hunting.

John Atherton

December 12, 1942

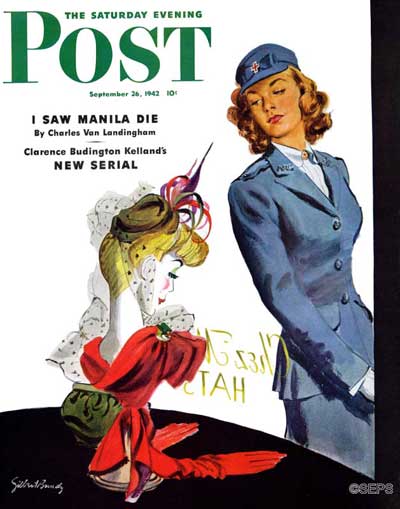

The enlisted also included members of the Women’s Army Corps (WAC), as shown in the cover from 1942 by an artist named Gilbert Bundy.

Gilbert Bundy

September 26, 1942

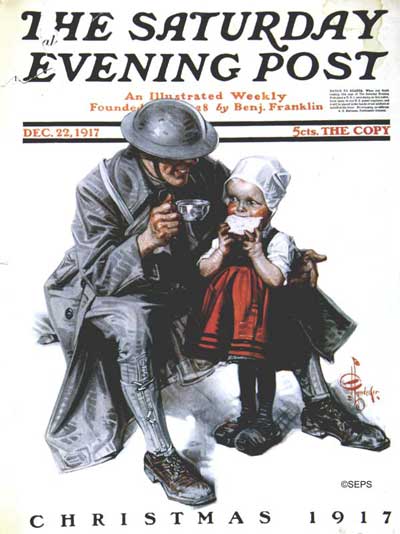

A WWI soldier shares a humble Christmas meal in this endearing 1917 cover by the prolific J.C. Leyendecker.

J. C. Leyendecker

December 22, 1917

On the May 14, 1927, cover by E.M. Jackson, this sailor accomplishes an important mission overseas — finding a genuine American hot dog!

E.M. Jackson

May 14, 1927

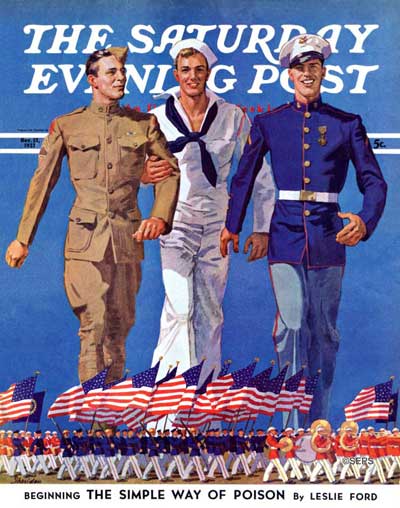

Celebrating soldiers, sailors, and marines, the 1937 cover by John Sheridan captures all three with a parade below in their honor.

John Sheridan

November 13, 1937

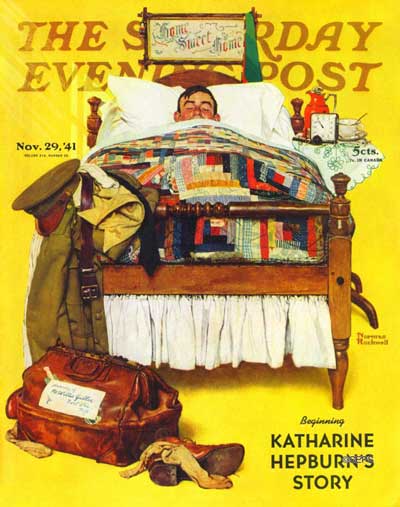

Norman Rockwell honored the military during the WWII years with several covers of the “every soldier” he named Willie Gillis. We’ve shown Willie’s military adventures before, but not this one from 1941. Rockwell’s famous private is home on leave, snuggled under the quilts and enjoying the luxury of sleeping late. The sign above the bed echoes our ardent wish for all our military men and women: Home Sweet Home.

Norman Rockwell

November 29, 1941

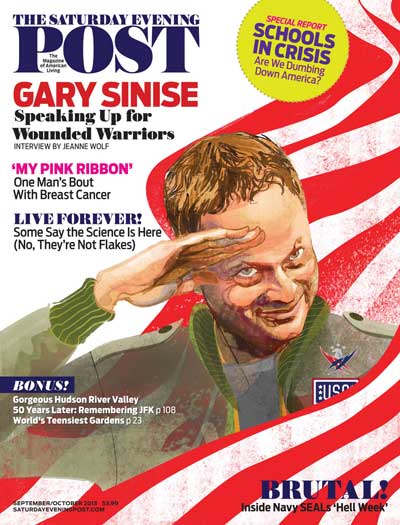

After Forest Gump, actor Gary Sinise became an advocate for wounded soldiers. Check out Jeanne Wolf’s interview with Sinise from the September/October 2014 issue here.

John Jay Cabuay

September/October 2014

John Atherton

John Atherton was born on June 7, 1900 in Brainerd, Minnesota, but his family moved to the West Coast shortly after his birth. John spent his high school years in Spokane, Washington, where he derived great satisfaction from nature. These elements would emerge in Atherton’s oil paintings as well as his commercial work in the years to come. Nature would also become a place in which John could collect his thoughts and refresh his creativity.

Atherton’s first recollection of an interest in art came when he painted a portrait of his aunt and received a favorable response. John completed his art education from the California College of Arts in San Francisco. In the process, he also worked in the surrounding studios developing his oil painting techniques. A first prize award of five hundred dollars financed John’s trip to New York, which helped launch his career. Atherton accomplished his first one-man show in Manhattan in 1936. His Painting, “The Black Horse” won the three thousand dollar fourth prize from among 14,000 entries. This painting now hangs in the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

As his career began to unfold, John Atherton found a rhythm that allowed him to develop his work in the both the artistic and the advertising arena. On November 2, 1926, he married Maxine Breese. Over time, the couple found themselves migrating to Westport, Connecticut which boasted an artistic community that rivaled none other. John Atherton’s first cover for The Saturday Evening Post was created in 1942, and continued with regularity until 1961. After a grand tour of the United States, this would become home for John’s wife Maxine and daughter Mary. The Atherton’s socialized with fellow artist, Mead Schaeffer and his wife which often lead to a variety of excursions which provided subjects to expound upon on canvas. The community provided not only a social outlet, but also a creative environment to cultivate and express his ideas.

It seems fitting that John Carleton Atherton would die as he lived, in tune with nature. His death occurred while he was salmon fishing in New Brunswick, Canada in 1952 at age 52.

Covers by John Atherton

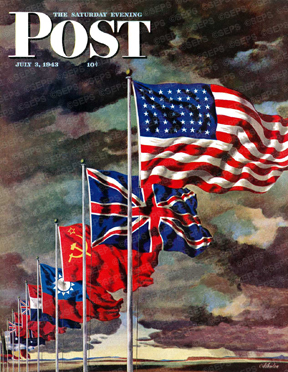

Allied Forces Flags

John Atherton

July 3, 1943

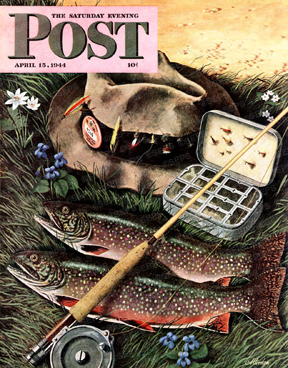

Fishing Still Life

John Atherton

April 15, 1944

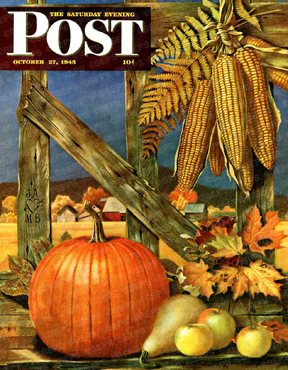

Fall Harvest

John Atherton

October 27, 1945

Classic Covers: Keeping Up with Yard Work

“Gardening requires lots of water — most of it in the form of perspiration,” said author Lou Erickson, and our Post covers prove it. Some people are downright persnickety in the care of their lawns and gardens while others are content to let Mother Nature take her course.

Definitely the odd couple. Mr. Felix is fastidious to the point where we believe the blades of grass salute as he walks by. Note how even the flowers stand at attention. But he isn’t all uptight: He is, after all, keeping up with the baseball game on his handy black and white TV while working. But in the July, 1961 cover by artist John Falter, Mr. Oscar next door is taking it easy, not at all bothered by overgrown hedges and toys on the sidewalk. Well, he probably had a hard week at work. Obviously, his dog did, too.

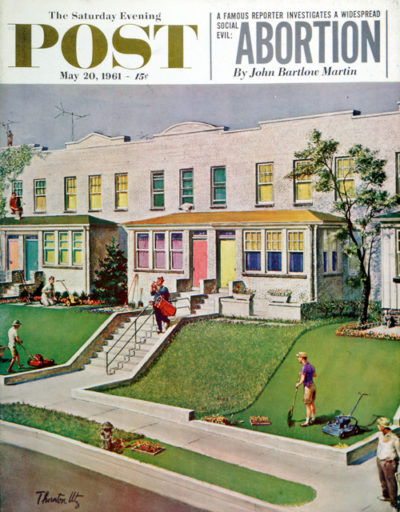

I'd Rather Be Golfing

May 20, 1961

On the other side of town, two equally fastidious neighbors are flummoxed—yes, that’s the word, flummoxed. In the May 20, 1961, cover by Thornton Utz, the lawn slaves work with push mowers and rakes while the guy from number 319 spends his Saturday as he darn well pleases, which includes lighting up a big cigar and taking his golf clubs for a walk, with nary a backward glance at his overgrown lawn.

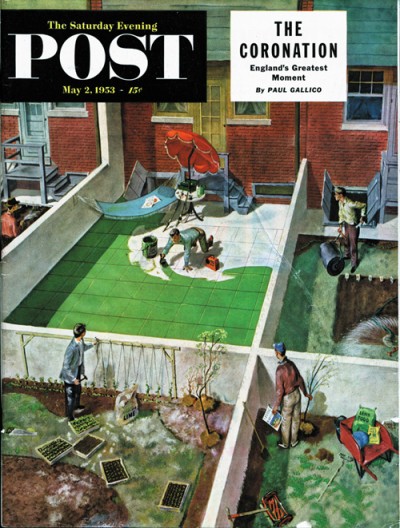

Painting the Padio Green

May 2, 1953

There’s more than one way to green up a lawn. In Utz’s May 2, 1953, cover, one man simply laid concrete and painted it green—and flummoxed neighbors appear once again. As the 1953 Post editors observed, “What sound-minded man would rest in a hammock when he can sprain his muscles spading the sweet earth?” Sound-minded or not, we have to give the guy points for ingenuity.

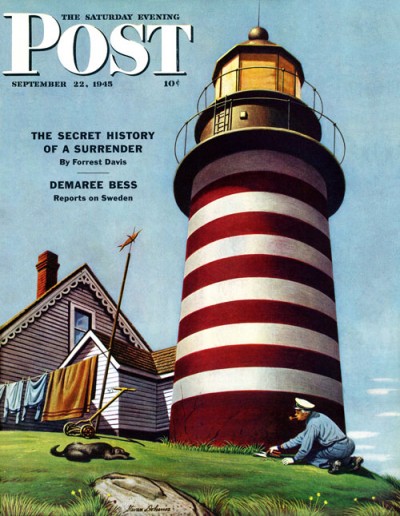

It isn’t only private lawns that need tending. Stevan Dohanos’ 1945 lighthouse, bold in red and white stripes, includes a busy groundskeeper neatly trimming the weeds, with no help whatsoever from the lazy pooch nearby.

Lighthouse Keeper

9/22/1945

Fond of finding gardens in unusual spots, Dohanos also painted the August 9, 1947, cover depicting three railroad workers watering a flower bed with the train looming right behind them—a cover to please both gardeners and train buffs alike.

Possibly the oddest spot for a garden was found by artist John Atherton. In a junkyard in Pittsburgh, no less, amid heaps of rusty scrap iron, the derrick operator planted a small garden. The enterprising man even made a fence around his plot using strips of scrap iron. “Gardens are a form of autobiography,” said Sydney Eddison, highly acclaimed gardening author and teacher, so it says much about the man that he seeks beauty amid the unsightly.

City Park

June 5, 1954

In Falter’s June 5, 1954, cover, as a man tends a downtown plot of flowers, his territory seems to be invaded by a spaceman after his baseball. Okay, some covers are just hard to explain—you’ll have to click on it and see for yourself. The older couple in Stevan Dohanos’ May 26, 1951, cover do the watering. Well, at least he is, and we must say that’s a lot of garden to water with a hose. When Post editors asked Dohanos, “What ate some of the lettuce and radishes in your picture—rabbits?” the artist replied, “Certainly not. People. No pests in my gardens. They don’t like the smell of paint.” Well, we warned you that artists are an odd lot.

Gallery

Lighthouse Keeper

9/22/1945

Tidy and Sloppy Neighbors

July 1, 1961

I’d Rather Be Golfing

May 20, 1961

Painting the Padio Green

May 2, 1953

Lemonade for the Lawnboy

May 14, 1955

City Park

June 5, 1954

Trainyard Flower Garden

August 9, 1947

Spring Yardwork

May 18, 1957