One-on-One with the Author: John Hemingway

The Saturday Evening Post enjoyed a long tradition for publishing short fiction. Historic contributors have included Edgar Allan Poe, Mark Twain, Sinclair Lewis, F. Scott Fitzgerald, William Faulkner, Agatha Christie, William Saroyan, and J.D. Salinger — among many others.

When we decided to restore fiction to the Post, it seemed appropriate to turn to the current generation of writers, progeny of our long-ago contributors. So, we asked John Hemingway, grandson of Nobel Prize-winning author Ernest Hemingway, to write an original story for you.

Imagine our surprise when we checked our files and could find no evidence that the Post had ever published any writing by Ernest Hemingway. The magazine was a mainstay for his friend Fitzgerald, but records show that the editors rejected at least three stories submitted by young Hemingway.

That was ironic, for biographers point out that Hemingway used fiction in the The Saturday Evening Post as a model for his early writing.

Hemingway recalled that in 1919 he was writing “stories which I sent to The Saturday Evening Post. The Saturday Evening Post did not buy them, nor did any other magazine. … I was always known in Petoskey as Ernie Hemingway who wrote for The Saturday Evening Post, due to the courtesy of my landlady’s son, who described my occupation to the reporter for the Petoskey paper.”

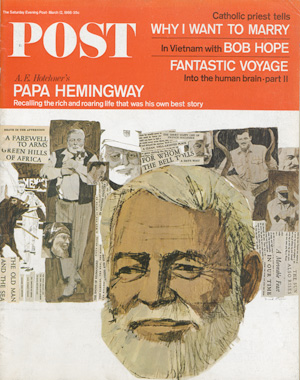

Ernest Hemingway did appear on the cover of the March 12, 1966, Post, but it was merely to promote a bio of him by his friend A. E. Hotchner.

Thus, this inaugural fiction by John Hemingway is a small recompense for our historical oversight.

John’s story of “Uncle Gus” may seem familiar to those who know his family history. He says, “It is, as I’m sure you figured out, based on my great-uncle Leicester, Ernest’s younger brother. He really was a generous person, a man of character.”

When we described it as a “pseudomemoir,” he acknowledged that as a “fair description,” adding that, “Fiction is often an embellishment of life.

“When I wrote Strange Tribe, it was a memoir dealing with my grandfather. That was a difficult book. Very stressful. If you get one detail wrong, they will crucify you. Therefore, it had to be rather scholarly. I had to stick with the facts.”

Short stories are another matter. They allow you to enhance the truth. “A short story is a very difficult form of literature, so concise, so compact, a kind of a poetry,” he observes. “With a novel or a memoir, you have the ability to take a break. You can’t do that with a short story. Every word counts.”

John wrote a number of short stories as a young man. “I’ve always liked short fiction,” he says. “I think my grandfather’s short stories were among his best writing.”

Turning serious, he says, “My objective is to write at least one story in my life as good as his.”

“Uncle Gus” was a daunting story to write. “It wasn’t the easiest choice,” he says.

John lived with his great-uncle Leicester for four years as a teenager. His mother was schizophrenic. His father had married another woman. “Les tried to make me feel like a part of the family, but I knew I had a father of my own.”

Nevertheless, this big bear of a man became an important role model for young John. “I’ll always remember his sense of family; his generosity.”

The memories come swirling back as he speaks. “I think of Les as being enormous. All that compassion.”

But Leicester’s own life was complex. “He was an eccentric, someone who lived in the shadow of his brother. He found it a challenge to live up to the image, to the greatness of the name.”

John faced the same challenge. “There was a difficult period in my 20s. I knew I was capable of writing, but I had to find my own voice. Then, I remembered something Les said his brother had told him, ‘You know you’ve written something great when you can make a person cry.’ ”

You will find a certain sadness in “Uncle Gus,” as well as the optimism of a young boy learning about the qualities of manhood.

“These values are not old-fashioned,” says John, his thoughts drifting back to 1977 when he was a boy of 17. “In fact, they’re extremely relevant today.”