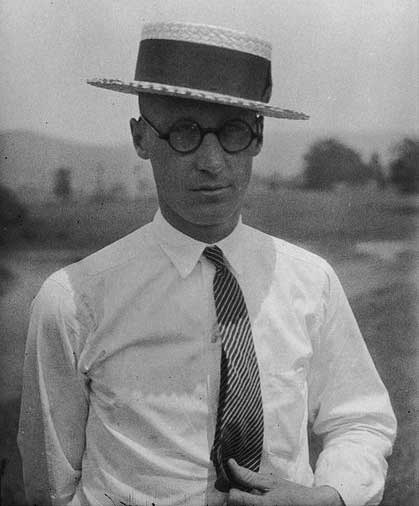

Whatever Happened to John Scopes, the ‘Monkey-Trial Man’?

It has come down to us a pivotal moment in American history, a classic confrontation between science and faith.

In 1925, John T. Scopes was arrested in Dayton, Tennessee, for the crime of teaching evolution in the local high school.

The resulting trial came mid-way through a decade that seemed obsessed with sensational stories. That summer, newspapers had given lurid coverage to the ongoing troubles with bootleggers, the excesses of jazz-crazed youth, critical response to Fitzgerald’s Great Gatsby, and the meaning of a parade by 40,000 members of the Ku Klux Klan through Washington, D.C.

But for many days that summer, the Scopes trial crowded every other story off the front page.

Over 100 newspaper reporters swooped down onto the town of Dayton, as well as throngs of tourists, not to mention pro-science and pro-Bible advocates eager for an audience. Street-corner preachers drew crowds of gawkers and idlers by damning Scopes and the theory that humans had “descended from a lower order of animals.” They demanded every sort of punishment for Scopes, just short of execution.

Also crowding into the little town was Scopes’ defense team, which included the nationally renowned lawyer Clarence Darrow. The prosecution team included former secretary of state and evangelist William Jennings Bryan. The trial became a spectacle as Darrow put Bryan on the witness stand and cross-examined his fundamentalist beliefs.

It all made for good copy, and it encouraged Americans to debate the meaning and consequences of the trial. Lost in all the noise, though, was the fact that the event—Scopes’ teaching from the state approved biology book on April 24, his subsequent arrest, and the trial, were all a stunt.

The American Civil Liberties Union wanted a test case to see if the Tennessee courts would enforce its new “Butler Act,” which outlawed the teaching of evolution.

The community leaders of Dayton, Tennessee, saw an opportunity to hold the test case in their jurisdiction and profit from the attention and tourism that would result.

John T. Scopes agreed to be the subject of the case. He was charged with having taught evolution on April 25, 1925, and quickly released on $500 bail posted by a Baltimore newspaper.

October 9, 1943. © SEPS 2014

If you’re familiar with the story, or you’ve seen its dramatized account in the play/film “Inherit The Wind,” you know Scopes was found guilty.

The sensational aspects of the story ended there, and few people are aware of what happened after the verdict. The judge set a fine of $100. Scopes’ lawyers appealed the verdict to the Tennessee Supreme Court, which supported the lower court’s verdict. However, the higher court—perhaps eager to get rid of the case—noted that the judge, not the jury, had set the amount of the fine. On this technicality, the Supreme Court overturned Scopes’ conviction.

The Scopes trial was one of the last great cases of Darrow’s career, and Bryan died just five days after the trial. Tennessee’s Butler Act remained in effect until 1967, at which point the state’s teachers were free to incorporate the theory of evolution into their biology curricula. In 2012, a new state law required science teachers to present evolution as a “controversial” and questionable theory.

And John Scopes? The ‘victim,’ according to some journalists? The ‘criminal’ whose punishment could not be too severe, according to others?

He appears to have slipped neatly back into the obscurity from which he had come.

Shortly after his conviction was overturned, he became a graduate geology student at the University of Chicago. He was later hired by Gulf Oil to look for oil deposits in South America. He wound up in Shreveport, Louisiana, studying oil reserves until his retirement in 1963.

“I’m just an ordinary man now, working to support a fine family,” he told the Post in October 1943. “Occasionally people will ask if I am ‘the John Scopes,’ but usually I just don’t think about it.

“I feel no guilt about the trial,” he said, adding quietly. “It was a long time ago, and I was pretty young then—too young.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article referred to Bryan as a former vice president. Bryan was a former secretary of state, not vice president.