A Captured General Goes Free

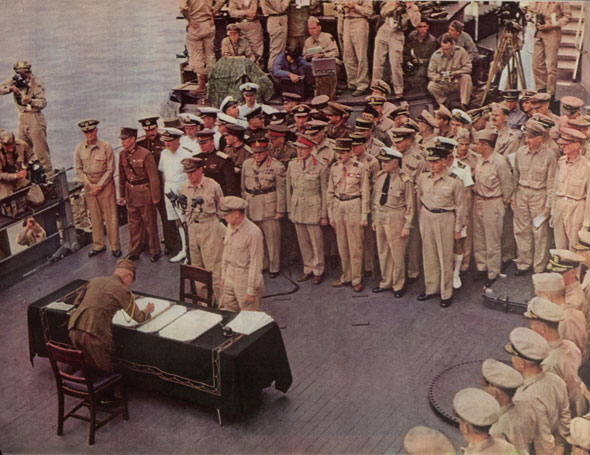

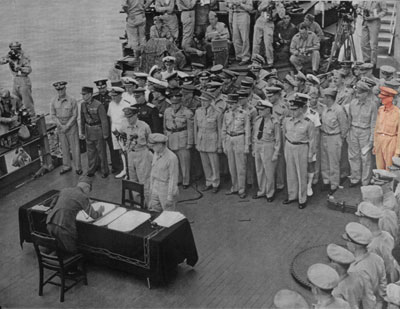

Note the man standing at the far right in this photo. The skinny gentleman wearing the baggy uniform?

His name is Jonathan M. Wainwright. And just 13 days before this picture was taken, he was being held in a Japanese POW camp.

Three years earlier, Wainwright commanded a force on the Philippine island Corregidor. The group included American and Philippine soldiers and American nurses who had fled Bataan after the Allied soldiers there surrendered to the Japanese.

General Wainwright tried to stave off a Japanese siege with an army of 11,000 soldiers who were exhausted, starving, and desperately short of medicine, fuel, and ammunition. On May 6, the Japanese forces finally breached his defenses. Fearing a general slaughter of his troops, Wainwright surrendered his command to the enemy.

Under Japanese warrior code, death was preferable to surrender and the captors regarded their new captives with vicious contempt. The captured were beaten, humiliated, tortured, and sometimes executed at the whims of Japanese soldiers.

Wainwright endured years of imprisonment, abuse, and starvation. But he was also burdened with a sense of remorse. He believed his country considered him a disgrace for ordering the surrender and becoming the highest-ranking prisoner of the enemy.

But then, in August 1945, they were liberated. And Wainright was shocked to hear he’d been promoted to major general; the United States considered him a hero. Flown back within American lines, Wainwright was given medical treatment, cleaned up, and given a fresh uniform. Within days, he found himself among the multinational dignitaries on the deck of the USS Missouri. America wanted to see him among the commanders who accepted the Japanese surrender.

This photo, which appeared in the Post on October 27, 1945, accompanied the story “The Japs’ Last Bite,” a report from newly defeated Japan. The article, by Bill Worden, reads like a Warner Bros. version of life in Yokohama under allied control. The cast includes the self-serving manager of a hotel, the escaped POW, the Jewish refugee from Germany, even a dog that had been liberated from a Japanese camp and, according to Worden, made the final gesture of the war.

There was no mention in this article, or any Post article for a year afterward, of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that brought the surrender. The country, and the Post, wasn’t ready to hear that story. They wanted to celebrate the heroes, and savor the moment of payback.