In a Word: Julius Caesar’s Ongoing Contributions to Language

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

The name Julius Caesar conjures a number of images in people’s minds. Some remember history lessons about the Roman general and dictator who died more than two millennia ago. Others recall seeing him on stage in a Shakespearean drama. Still others picture the statue standing watch outside a popular casino on the Las Vegas Strip.

But there’s even more to the name Julius Caesar than a singular man. His name is the starting point for a linguistic legacy that has spanned continents, and it still has relevance in Modern English. It all began when he decided he needed an heir.

Gaius Julius Caesar adopted his grand-nephew Octavius after Octavius’s father died. According to Roman naming conventions, Octavius took on his adoptive father’s name — the whole name. He became known as Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus, often shortened to the anglicized Octavian today when talking about his early life.

As we all know, the Ides of March of 44 B.C. were not great for Julius Caesar, but they weren’t horrible for Octavian. In Julius’s will, he named Octavian as his heir, not only to his estate but to his power. So after the assassination — and some political and military maneuvering — Octavian assumed the role of emperor of the Roman Empire. After he defeated Marc Antony and Cleopatra, the Roman Senate bestowed a new title upon him: Augustus, meaning “illustrious one.” Octavian became Augustus Caesar, and his reign ushered in the Pax Romana.

When it came to lineage, Augustus followed in Julius’s footsteps: He adopted a boy, his stepson Tiberius, and named him his heir, bestowing upon him the name Caesar. Thus a trend was established among Roman emperors of identifying the next in succession by bestowing the title Caesar upon him, a title which was kept after ascension to power.

English contains a lot of words that are derived from Latin, in large part because of the expansion of the Roman Empire and the language it took with it. Caesar is one of those words that found its place in the farthest reaches of the Roman Empire — in fact, it was one of the first Latin borrowings into the Germanic languages. Translated into different tongues, caesar became synonymous with emperor. We find it in Old English as cāsere, and it appears in Middle English as keiser. On the continent, it became the German and Austrian Kaiser, the title that would be used by the emperor of Germany through the end of World War I.

The word caesar also evolved through the Slavic languages and into Russian, where it became czar or tsar, a title first adopted in 1547 by Ivan IV, Emperor of Russia. A German ambassador to Russia —Siegmund, Baron von Herberstein — brought the Latinized transliteration czar back to Europe in 1549, likely influenced by German spellings. Though the etymological link to Caesar is more apparent in the spelling czar, tsar is a more straightforward borrowing from the Russian.

Nonetheless, American political discourse latched on to the spelling czar, and pundits used it to indicate someone with practically dictatorial powers. In the 1970s and ’80s, we had, for example, an energy czar (John Love) and a drug czar (William Bennett), and the title keeps returning for many an administrative post — though never officially.

But we’ve been using the word to make political statements for longer than you might think: Adversaries of Nicholas Biddle, president of the Second Bank of the United States, were calling him “Czar Nicholas” in the early 1830s. And it popped up again in 1866, with opponents of President Andrew Johnson dubbing him “Czar of All the Americas.”

Julius Caesar’s linguistic legacy isn’t limited to emperors and dictators, though. His name is also the source of Caesar’s agaric (an edible mushroom also called royal agaric) and, supposedly, caesarean section, a phrase that has been around since at least the early 17th century. Legend has it that Julius Caesar was cut from his mother’s womb, but that isn’t likely — at the time of Caesar’s birth, such an operation would have been rare on a living woman and would most certainly have killed her, and history shows that Caesar’s mother lived to see him become one of Rome’s greatest generals. It’s more likely that caesarean (and perhaps Caesar’s name) is derived from the Latin caedere “to cut.”

One thing that is not part of Julius Caesar’s lexical ancestry: the Caesar salad. That was named for Caesar Cardini, the man who invented it in 1924.

Featured image: Shutterstock.

10 History Facts You’re Probably Getting Wrong

“It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble,” Mark Twain once wrote. “It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

To help you avoid a little trouble in the future, we present a handful of historical myths that are commonly believed, but “just ain’t so.”

1. “Caesarean Section” got its name from Julius Caesar, who was born by this method of delivery.

No records indicate Caesar was born by C-section. In fact, doctors in ancient Rome only performed this procedure on mothers who were dead or dying, and Caesar’s mother was reported to still be alive when Caesar was in his 40s. The word “caesarean” is probably an alteration of older Latin words for “cut” or “postmortem birth.”

2. Nineteen women accused of witchcraft in Salem, Massachusetts, were burned at the stake.

No “witches” were burned at the trials, which took place between February 1692 and May 1693. All nineteen women were hanged. Although no Massachusetts women were burned at the stake, it is estimated that many European women were. Of the 40,000-50,000 women who were executed for being witches, burning was the preferred method because it was said to be the most painful.

3. All men in the Revolutionary War era wore wigs.

Wigs became popular in the 1600s when an outbreak of sexually transmitted diseases caused many men to lose their hair. By the 1700s, long hair was still stylish, but wigs were on their way out. A historian at Williamsburg estimates that 5% of the population in colonial Virginia wore wigs.

Soldiers kept their hair long, but they powdered it to make it resemble the powdered wigs of the previous century. George Washington’s hair, which you see represented on the quarter and dollar bill, was all his own.

4. On the night of April 18, 1775, Paul Revere rode through the Massachusetts countryside, shouting “the British are coming.”

The purpose of Revere’s ride was to warn the militias in Concord that the British regular troops were on their way to seize weapons and supplies the patriots had stored there. He was also ordered to warn Samuel Adams and John Hancock in Lexington that the British would probably be coming to arrest them. He did not shout “the British are coming” because it would have made no sense. At this point, most colonists still thought of themselves as British. And he wouldn’t have shouted in general because he was trying to avoid arrest by British regulars on the road.

Revere alerted the militia in Medford and Arlington before reaching Lexington and passing on his warning to Adams and Hancock. Revere proceeded to Concord but was caught by the British, questioned, and released. End of ride.

5. There were no survivors from the Alamo.

After overwhelming the men holding the Alamo in 1836, Mexican troops executed 200 of the surviving soldiers. However, 13 wives and children of Texan soldiers were allowed to leave. The Mexicans also released a slave of William Travis and a Hispanic man who fought with the Texans but convinced the Mexican soldiers he had been a captive.

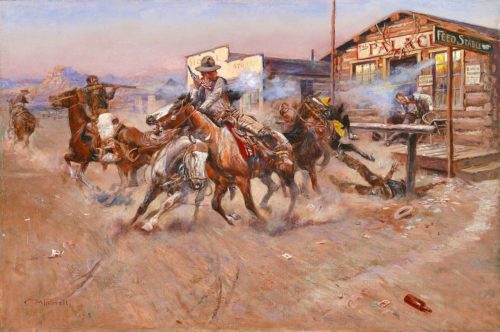

6. The early days of the American West were a time of widespread lawlessness; shootings were common, as were bank robberies.

The truth of this assertion is hotly debated, with both sides citing quite different figures. However, one statistic shows four Kansas cow towns were more peaceable than their reputations. Between 1870 and 1885, the number of gunshot deaths in Wichita, Abilene, Dodge City, and Ellsworth was 45.

The total number of bank robberies in 15 western states between 1859 and 1900 was probably less than 10. By way of comparison, there were over 4,000 in the U.S. in 2016.

7. Thomas Edison invented the light bulb in 1879.

At least two men were ahead of Edison in the light bulb’s development. In 1802, Humphrey Davy created an electric arc lamp, and in 1840, Warren de la Rue produced a light bulb with a platinum filament.

8. After the Wall Street crash of 1929, many stock brokers committed suicide by jumping out of the windows of their offices.

The suicide rate in Manhattan rose only slightly after the crash. Only two men are reported to have jumped from a tall window. (The rate of suicides was actually higher in the summer months before Black Friday.)

9. Charles Lindbergh was the first man to fly nonstop across the Atlantic ocean.

John Alcock and Arthur Brown flew a Vickers Vimy biplane across the Atlantic in 1919. They took off from Newfoundland and landed in Ireland.

10. Every statue of a military hero on horseback tells the fate of the rider. If one hoof is raised, the rider was wounded in battle. Two hooves raised meant the rider died in battle. And a horse with all hooves down indicated a hero who survived all battles.

This rule of — hoof? — is not dependably true. For example, some of the equestrian statues at Gettysburg follow this code, but not all. In Washington D.C., only a third of 30 statues of heroes on horseback comply with this custom.

Featured image: Shutterstock