Considering History: Kamala Harris’s Heritage and the Legacies of Slavery and Sexual Violence

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

In the immediate aftermath of Joe Biden’s selection of Senator Kamala Harris to be his vice presidential running mate, a controversial Newsweek article raised questions of whether Harris, the daughter of two immigrants, would be eligible to serve in that role if elected. The article, authored by a right-wing law professor who had previously run against Harris for the position of California’s Attorney General, doesn’t hold legal water; Harris was born in Oakland and so was, from birth, a United States citizen, as guaranteed by the 14th Amendment. But the article has reignited debates over that Constitutional concept of birthright citizenship, one that President Trump has at various times expressed a desire to do away with.

While Harris’s own citizenship status under that existing law is clear and indisputable (as Newsweek has subsequently admitted), there is another, more genuinely complex part of her heritage and family that has also received renewed attention since the VP announcement. In 2018, Harris’s father Donald, a Jamaican-American immigrant and retired Stanford University economics professor, wrote an article about his Jamaican ancestors in which he argued that he is descended on his father’s side from the infamous 19th century white slave owner Hamilton Brown, who ran one of the island’s largest plantations and was responsible for the importation and enslavement of hundreds of Africans.

Donald Harris’s claims about his relationship to Hamilton Brown have been used by conservative pundits like Dinesh D’Souza and others as a “gotcha” moment, as the basis for arguments that neither Harris nor her supporters can discuss the legacies of slavery and racism since she herself is descended from a white slave owner. But in truth that heritage, which is shared by a significant number of Americans of African descent, reflects one of the most essential and too-often forgotten histories of slavery and the sexual violence that accompanied it. And if we set aside political and partisan concerns, Harris’s story can help us understand those vital histories of slavery, sexual violence, race, and heritage, the legacies of which are certainly still with us in 21st century America.

One of the most consistent and central elements of chattel slavery, as it was practiced throughout the Americas, was the rape of enslaved women by male slave owners. It is difficult if not impossible to ascertain the percentage of enslaved women who were so violated (and thus of enslaved children who were the product of such acts), both because the practice was so ubiquitous and because it was for centuries under-narrated in histories of slavery. The latter trend has been challenged in recent years, as illustrated by historian Rachel Feinstein’s When Rape Was Legal: The Untold History of Sexual Violence During Slavery (2019) among other works.

Another recent trend that has made it more possible to grapple with these histories is the rise of ancestry studies and the corresponding use of DNA analysis to trace heritages. For example, the scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr., a pioneer in the use of such data to analyze individual, familial, and collective ancestries, estimates that “a whopping 35 percent of all African-American men descend from a white male ancestor who fathered a mulatto child sometime in the slavery era, most probably from rape or coerced sexuality.” And since that number reflects 21st century identities and all the other factors that have contributed to them, it likely only scratches the surface of how widespread these practices and their effects were in the era of slavery.

While many of those experiences are unfortunately lost to history, individual case studies can help us engage with the aftermath of sexual violence under slavery. As I highlighted in this July 4th column, the story of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings offers one particularly prominent such case study. After nearly two centuries of rumors and debate, both DNA analysis and the pioneering work of scholar Annette Gordon-Reed have confirmed that Jefferson did rape and father at least one child (and almost certainly six or more children) with Hemings, one of the enslaved women on his Monticello plantation. Historians have only begun to uncover the complex stories of the descendants of those sexual assaults, enslaved young men and women who, despite their famous father and the promise of freedom that came with that status, still experienced some of the worst of antebellum American slavery and racism.

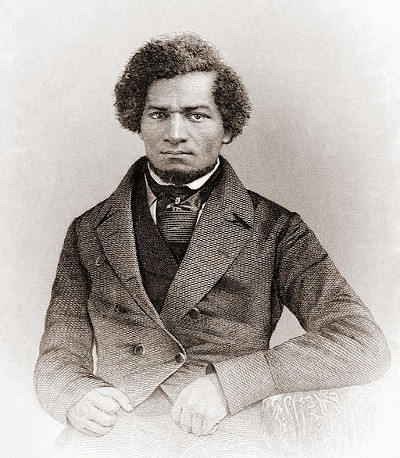

Another of the 19th century’s most famous Americans, Frederick Douglass, experienced life as the child of sexual assault under slavery. In the opening chapter of his 1845 Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Douglass notes his belief that his father, whom he never knew, was the white slave owner of the Maryland plantation onto which he was born. As usual with his autoethnographic works, Douglass uses this personal detail to illuminate social and historical meanings, noting for example that the law making the children of enslaved women themselves slaves “is done too obviously to administer to [slaveowners’] own lusts, and make a gratification of their wicked desires profitable as well as pleasurable; for by this cunning arrangement, the slaveholder, in cases not a few, sustains to his slaves the double relation of master and father.” But Douglass also empathetically notes the potentially painful effects for all involved, from masters having to sell their own children to “one white son” having to “ply the gory lash to his [brother’s] naked back.”

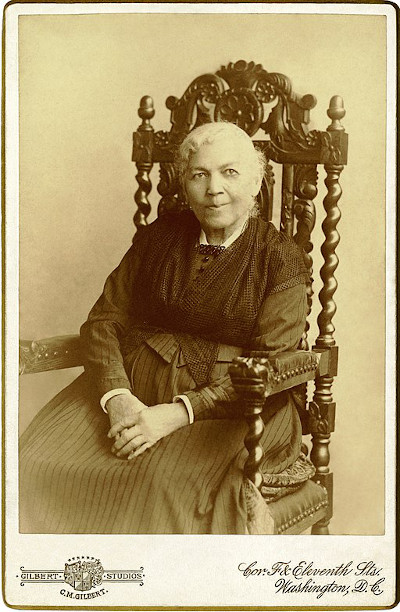

Douglass did not have the chance to know his mother well before her tragic death, so he was unable to write about her perspective. But another prominent personal narrative of slavery, Harriet Jacobs’ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861), captures the experience of enslaved women under the constant threat of sexual violence. As Jacobs puts it in her chapter “The Trials of Girlhood,” “there is no shadow of law to protect her from insult, from violence, or even from death; all these are inflicted by fiends who bear the shape of men…She will become prematurely knowing in evil things. Soon she will learn to tremble when she hears her master’s footfall. She will be compelled to realize that she is no longer a child.” And through her own constant battles with her despicable master Dr. Flint, Jacobs traces how “the influences of slavery had the same effect on me that they had on other young girls; they had made me prematurely knowing, concerning the evil ways of the world.”

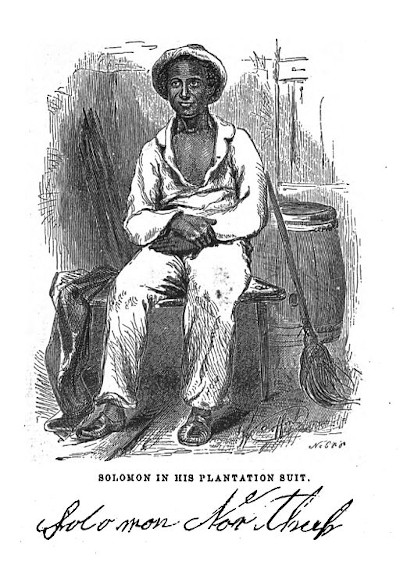

Individuals like Douglass and Jacobs managed to escape the horrors of slavery and publish their stories. But of course the vast majority of both enslaved women raped by their owners and the children of those rapes remained enslaved throughout their lives. We get a glimpse of such experiences in another personal narrative, Solomon Northrup’s Twelve Years a Slave (1853). At the final plantation to which Northrup is taken, he meets Patsey, an enslaved young woman whose beauty and strong will make her a singular focus of her owner Edwin Epps. If not enslaved, Northrup writes, Patsey “would have been chief among ten thousand of her people”; but on the Epps plantation, this impressive young woman becomes instead “the enslaved victim of lust and hate,” with “no comfort in her life.” Although the illegally kidnapped Northup is eventually rescued from the Epps plantation, he can do nothing for Patsey; a tragic reality captured in a culminating scene from the 2012 film adaptation of 12 Years, as Northup (Chiwetel Ejiofor) watches Patsey (Lupita Nyong’o) recede as he rides away from the plantation.

No one can blame Northup in this moment, as there is nothing he can do for Patsey. But for far too long, both our laws and our collective memories likewise abandoned enslaved women like Patsey and their children to sexual violence and its effects. We cannot change the past, but—with heritages like Kamala Harris’s to help guide us—we can remember those histories and consider all that they mean for all Americans.

Featured image: Kim Wilson / Shutterstock