North Country Girl: Chapter 12 — Country Club Days

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

My sister Lani and I arrived home to the big news that my dad had switched country clubs. For years he had played golf at Ridgeway Country Club, a mysterious place with a ramshackle clubhouse that I had only glimpsed from the outside when my mom dropped off my dad and his club. Ridgeway members golfed, drank, smoked, and played cards; there were no Ladies’ Days or children’s programs.

Now my dad was a member at Northland Country Club, about as waspy a place as could be in Duluth. No Jews of course, and the inclination would probably have been to exclude Catholics as well, except that Duluth had a deep base of Norwegians who were local business and government bigwigs, as well as supporters of the Church.

Northland’s clubhouse was a gleaming white pseudo-mansion that would not have looked out of place on an antebellum plantation, complete with porte-cochere in the front and a two-story columned patio on the side. There was even a guardhouse at the turn off of Superior Street where you had to stop to have your name checked against the membership roll before proceeding up the long driveway. At the top, nestled beside the clubhouse, was a (semi-) heated pool. After being frog marched into the frigid water of Hanging Horn Lake for swimming lessons at camp, Lani and I took the Northland pool as if it were the Caribbean. The only other pool I had been to in Duluth was the indoor one at Woodland Junior High, where I was forced to take swimming lessons year after year, never passing into a higher category than Minnow. It was impossible to learn to swim in that over-chlorinated, dimly lit Woodland pool. It had a ledge all around it made of concrete mixed with pumice and bits of sandpaper that would take the skin off your legs and arms, and was surrounded by tiles so slippery that anything faster than a trudge resulted in immediate expulsion from the swimming class. And since the pool was inside the school, it was thought not necessary to heat it.

Thrilled with the chance to swim in water that was over 70 degrees, Lani and I spent the rest of the summer begging, “Can we go to the pool? Can we go to the pool?” from the time we woke up. When we got to Northland, Lani and I (always having to wait the mandatory thirty minutes if we were there after lunch) gleefully plunged into the pool, tossing beach balls, playing water tag, having breath holding contests, going off the diving board (only allowed after you proved you could swim the length of the pool) and staying in the water all afternoon, emerging at five when the pool closed, blue-lipped and prune-fingered.

Oddly enough, none of my classmates’ families belonged to Northland and most of the kids who were regulars at the pool were younger than I. Lani’s best friend Julie Luster often joined us while her mother golfed or drank at the club bar on Ladies’ Day. Children were not allowed to be at the pool by themselves. Your mother or another member had to sign you in and stay there, so there was always a circle of trapped moms trying to get a hint of a tan from the weak Minnesota sun while regularly being drenched by kids cannon-balling or getting in a forbidden game of chicken while the lifeguard’s back was turned.

Northland’s pool, snack bar, hamburgers and fries served on the patio — along with family Fourth of July parties with sack races, hot dogs, and fireworks — was heaven enough for me. But my parents wanted me to enjoy all the benefits of Northland membership, which included golf and tennis lessons for kids. I had learned to hate tennis at camp, but golf brought me to new levels of wishing I never had to do anything besides sit on the sofa and read. Mini-golf was fun; colored balls, little windmills, a chance to hit your sister with the putter. Golf lessons were ten weeks spent just on my stance, swinging the club at an imaginary ball, then having my body manipulated by a creepy assistant golf pro so I could swing at nothing again. When I was finally given a real golf ball, I managed to sideswipe it, knocking the ball off the tee onto the grass. I was ordered back to stance school, at which point I put my club and feet down and refused to go to golf lessons ever again.

***

In fifth grade I was one of the white mice in another of Duluth’s experiments in education. As a result of all that testing the year before, it was determined that five Congdon fifth graders — me and four boys — deserved “enrichment education.” We would spend our mornings in a special class at Endion Elementary and afternoons at Congdon. I have no idea how my Congdon teacher, the huge Miss Johnson, felt about this. During all my previous elementary school years, there was never any schedule for the day. After we said the Pledge of Allegiance, we might have math or social studies or reading, whatever the teacher felt like teaching. We would go weeks without taking out our music books and then sing for an hour every day for three weeks. But because the five of us would receive “enriched” instruction in English and social studies, Miss Johnson was forced to structure her day to cover those subjects in the morning. In the afternoons, when we were back at Congdon, Miss Johnson would teach math, a smidgen of science (none of those spinster teachers cared about science at all), art, music, and whatever else needed to be taught.

Since there were five of us, the five mothers each took a day of the week to pick all of us up (two kids in the front, three in the back, and please please please don’t let me be squeezed between two boys) in the morning, then shuttle us back to Congdon in time for lunch. It was kind of a requirement for our enriched education, as no other form of transport was offered. My mother bitched — as probably the other four mothers did — every time her day to drive came around.

I loved the Endion Elementary enrichment classes, and I adored our teacher. Miss Steinbeck, a classicist, took us through ancient history, from Egypt to Rome. We wrote stories set in those eras, acted out Greek myths, built a tiny Acropolis, studied sculpture and urns and pyramids. It was a geek’s paradise.

It was also the perfect way to make a socially awkward girl like me even more so. Just being out of my regular Congdon class half the day made me an oddball. When I had nothing more exciting to report to my classmates about the mysterious doings of our morning enrichment class than “We looked at hieroglyphics,” I went back to being ignored and then even further alienated from fifth grade girls’ society.

The educational powers that be weren’t done yet. Several students were also pulled out of Miss Johnson’s room one afternoon a week for a special creative writing class, including Nancy Erman, the one friend I had left. I was consumed with jealousy, as it was universally accepted that I was the best writer in fifth grade. Being told that the only reason I didn’t get to go to creative writing was because I was already pulled out of class half the day did not make me feel any better, and I am afraid I was a snotty little bitch to Nancy for quite a while.

Because I was not enough of a weirdo, there came the afternoon when Miss Johnson escorted the girls out of the classroom and down to the gym. Everyone, she announced, “except Gay. Your mother didn’t sign the permission slip.” Every eye, boy and girl, turned towards me as I tried to will myself invisible. Two hours later, the girls returned, giggling and pinching each other. I was too humiliated to ask what I had missed.

I finally got Nancy to tell me. It was a movie about menstruation, sponsored by Modess sanitary pads, starring a caterpillar who turns into a butterfly. Obviously all the other girls would now metamorphose into butterflies while I would remain a lowly caterpillar. I held back my tears till I got home, where my hysterics were poo-pooed by my mother, the cause of my shame. She had received the letter from the school about the movie, decided I was too young to learn about these things (I had kept the info shared by the Applebaum cousins to myself), and tossed the permission slip into the garbage. “I didn’t know you’d be the only one,” she shrugged.

My sex education was complete enough to be equally thrilled and embarrassed when my mother announced that she was pregnant. To me, my mother always seemed much younger than other moms; Nancy Erman had a brother and sister who were in college and her grey-haired mother seemed as old as my grandmothers. The year before my parents had been photographed for the Duluth Tribune learning to do that new dance craze, the Twist. The world had not yet been turned over to teen-agers; thirty-year-olds could still be cool.

Around the time my mother’s pregnancy began to show, other women started asking with suspicious frequency how old she was. Mom, who had always been paranoid about revealing her age, thought they were hinting about getting pregnant at her advanced age, and refused to answer. I heard her constantly griping, “Old biddies, why do they want to know how old I am?” Someone clued her in to the fact she was being vetted for the Junior League, a club that believed itself to be the pinnacle of high society among Duluth women. My mom had been nominated for Junior League but there was a hitch: you had to be under 35 to join the Junior League. But no one came out and said that why she was asking about my mom’s age, I guess in case my mom got blackballed, so she wouldn’t have hurt feelings.

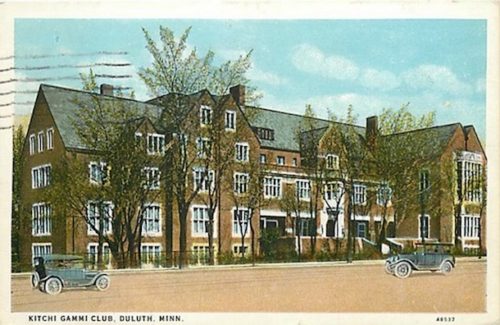

Duluthians of that time loved joining things: churches (everyone belong to some church, Catholic, Lutheran, Congregationalist, even the mysterious Jewish temple), country clubs, Elks, Moose, Rotary, Lion’s Club, the weird Knights of Columbus and the even odder Masons. My mother was a member of the Women’s Dental Auxiliary and drove around the county distributing toothbrushes and toothpaste to rural schools. My Carlton grandmother was a member of the hoity-toity Kitchi Gammi club, where I was once invited to lunch with her in its cavernous, echoing dining room.

I must have done something wrong — pushed my soup spoon the wrong way or stained the snowy table cloth — as the invitation was not repeated. Grandma Marie was also a member of the Women’s Club, the mother organization to the Junior League, a bunch of do-gooders who were best known for the Duluth Women’s Club Parade of Homes, a chance to poke around in other people’s over-decorated houses for charity.

Why my grandmother Marie couldn’t have just shepherded my mom into Junior League is a mystery. Maybe she was too much of a snob and thought a house painter’s daughter from Aberdeen, South Dakota, even if she was her daughter-in-law, wasn’t good enough to raise money for the Duluth Symphony or the Leif Erickson Park rose gardens.

Alas, my mother never became a Junior Leaguer. Even in an organization composed entirely of women, the husbands had to be considered. My father missed the mandatory Saturday breakfast meeting where my mother was to be interviewed for inclusion in the club; he was too hung over. The Junior League gave him a second chance, he missed that one too.