Pen Pals with the Killer of Kitty Genovese

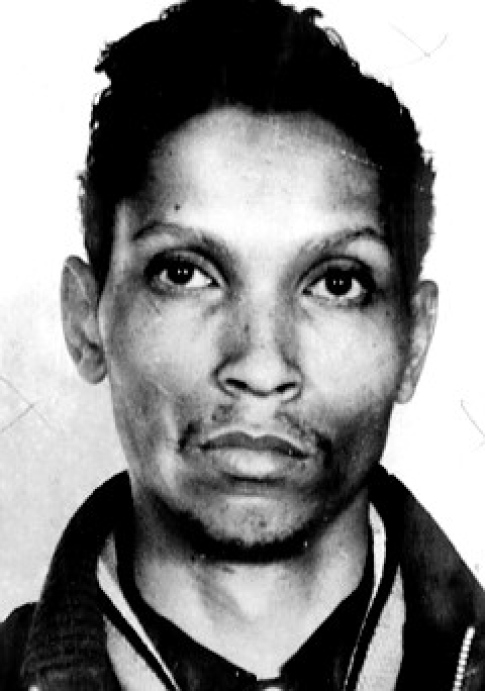

Years later, Winston Moseley would describe it as a robbery that went wrong.

He claimed he’d never seen Kitty Genovese before, and he had no intention of harming her.

But when she saw him on the morning of March 13, 1964, in her New York neighborhood, she started to run away. Moseley said, “I kind of lost my head.” He pursued her and then stabbed her twice. Crying for help, she collapsed to the ground. A neighbor, hearing her cries, shouted out his window, demanding to know what was going on. Moseley ran away, and the neighbor saw Genovese rise and walk into her apartment building. Once inside, she collapsed on the entryway floor.

After getting away from the scene of the crime, Moseley slowed and thought. And then he went back to his victim and killed her. The murder became infamous for the number of witnesses to the crime who did nothing to help her (although many of the facts in the New York Times story that appeared two weeks after her murder were later questioned and found to be grossly exaggerated). Still, 55 years later, the murder is remembered as an example of what can go horribly wrong when everyone thinks, “I shouldn’t get involved.”

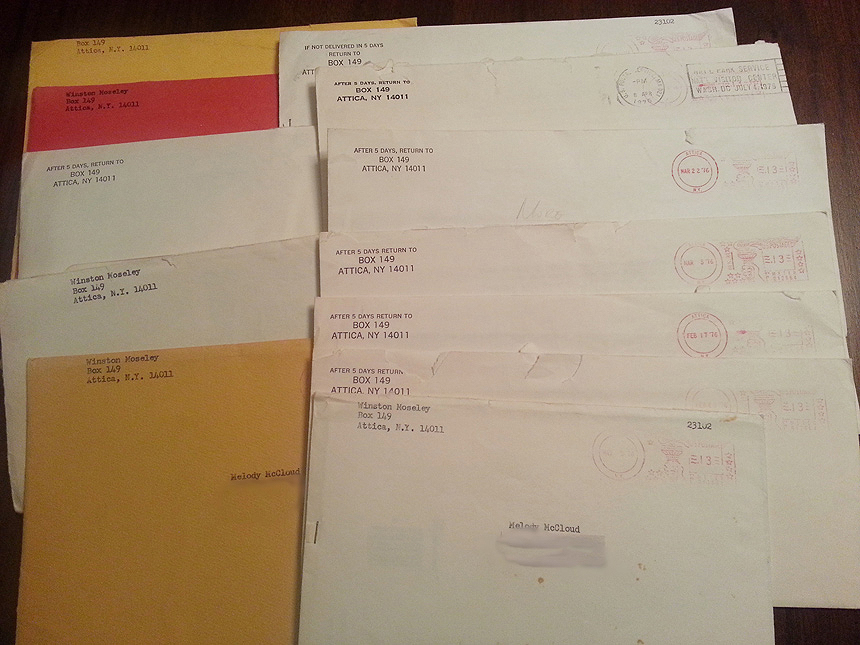

One woman who got involved — albeit inadvertently, and years later — was Melody McCloud. Moseley’s account of his murder of Genovese is detailed in a series of letters he wrote to McCloud, then a pre-med student at Boston University.

While still in school, she’d been involved in a prison ministry, sharing the message of forgiveness and redemption with prisoners. Later, in 1975, she saw a television news story about Moseley, in which he was identified as “Inmate Liaison to Attica Correctional Facility.” He told the reporter he was working to improve conditions for prisoners following Attica’s deadly riot in 1971. Although Moseley was a total stranger, McCloud wrote him a letter of encouragement in his liaison work. The next month, she received a letter back from him, and a correspondence began.

Over the next five months, he wrote twelve letters. Some included poems or cards. It was in his third letter that he wanted her to know about his conviction “right from the start so you can decide whether or not the facts…are going to make any difference to you.” He told her that he was the murderer of Kitty Genovese in 1964 and once escaped from custody.

The name “Genovese” sounded familiar. She recalled that the case had been a big deal at the time. She looked up details in the library and discovered that Moseley had confessed to murdering two other women — Barbara Kralik and Annie May Johnson — and was accused of forty robberies and various assaults and rapes.

McCloud was stunned by what she read. She recalls thinking, “What’s a nice girl like me doing in a story like this?”

She wrote back to Moseley about what she’d learned. He responded to her questions about Kralik. He also described, at length, his mental state the night of Genovese’s murder.

He’d felt defeated by his two divorces and separation from his children. His parents, to whom he was very close, had been having serious problems for years. He wrote that it created “a psychological disturbance for me.”

After attacking Kitty and running away, he wrote, “what I went back for was some vague notion of taking her to a hospital.” After putting on a wide-brimmed hat to avoid recognition, he returned to her apartment building. He found Kitty on the floor of her building’s entry. When she saw him, he claimed, she began using abusive, racist language. In his letters, he wrote “I stopped being human.” Overcome with hatred, he attacked her again, stabbing her repeatedly while she called for help.

Moseley wrote that he didn’t feel hurried because he knew no one would come, no one would interfere.

“I didn’t want to get involved,” was reported to be a common excuse of the witnesses. The incident gave rise to a new, sinister, phenomenon: “bystander syndrome,” a symptom of urban life in which people abandoned their sense of responsibility and human connection.

In response, residents of New York City began neighborhood watch patrols. And the city established the first 911 system for calling the police.

Later investigation contradicted the claim of 38 inactive witnesses. Moseley said the number had been exaggerated to make the crime sound worse. It was certainly bad enough, becoming the most infamous murder in a year that saw 630 murders in New York. But this crime magnified New Yorkers’ fear that they couldn’t count on others for help in an emergency.

Less than a week after murdering Genovese, Moseley was captured while burgling a house. He confessed to the murders of Genovese, Kralik, and Johnson.

After learning the details about Moseley’s past, McCloud continued to write, but not as often. She began easing away from the correspondence, telling him she was too busy. “How can you be so busy you can’t write?” he challenged in his next letter. He was angry, she says, and he added threateningly, “you better be careful!” In a later letter, he apologized for his anger.

Their correspondence ended in May of 1976.

Moseley remained in prison until his death in 2016. During his 52 years in prison, he had applied for, and was denied, parole 18 times.

While Moseley lived, McCloud, who is now an obstetrician-gynecologist and author who lives in Atlanta, Georgia, did nothing with the letters.

Today, her collection of letters offers a unique insight into the mind of a serial killer, made even more valuable for their candor. “I was not anyone who could really help him,” she says. “I was just a kid, basically. So I don’t feel he had anything to gain by lying to me about his psychological state.”

For 43 years, Dr. McCloud has held onto these letters, not wishing to publicize them while Moseley lived. This year marks the 55th anniversary of Genovese’s death. It’s time, she says, to share their contents.

Feature image credit: Courtesy Dr. Melody McCloud. Used with permission.

The Murder of Kitty Genovese: 50 years later, questions remain

Of the thousands of killings that took place in New York in the 1960s, none drew more attention that the murder of Kitty Genovese.

On March 13, 1964, the 28-year-old woman was attacked on her way home to a respectable, middle-class neighborhood in Queens. While walking up to her apartment building, Winston Moseley, a total stranger to her, stabbed her in the back.

Genovese screamed, “Oh, my God, he stabbed me! Please help me, please help me!” Lights went on in a window above and a man leaned from his window to shout, “Hey, get out of there. What are you doing?” and Moseley fled.

Genovese staggered to her nearby apartment building. Once inside, she collapsed in the hallway, just 50 feet from her door. She was still calling out for help when Mosley returned to resume his attack.

What set this murder apart from the thousands of other homicides was the chilling loneliness of her death. None of Genovese’s neighbors came to her aid. No one even phoned the police until a half hour from her first cry for help. As the Post later reported, “In what has become a celebrated example of good reporting, The New York Times discovered and disclosed that 38 otherwise respectable and law-abiding citizens either saw or heard a part of the Kitty Genovese murder in progress, yet only one bothered to call police for help, and that wasn’t until the killer had fled” (“Who Didn’t Kill Barbara Kralik,” January 16, 1965).

The story prompted a wave of self-examination across the country. Americans wondered how their countrymen could stand by and watch a woman being brutally murdered, screaming for help that over three dozen people refused to give.

Such callous indifference seemed unbelievable, but it was consistent with the rising violence Americans were seeing. In the past year, they had read of the murders of both President Kennedy and his assassin, as well as the beatings and killings of civil rights activists. Genovese’s brutal murder and abandonment seemed consistent with this dangerous new age.

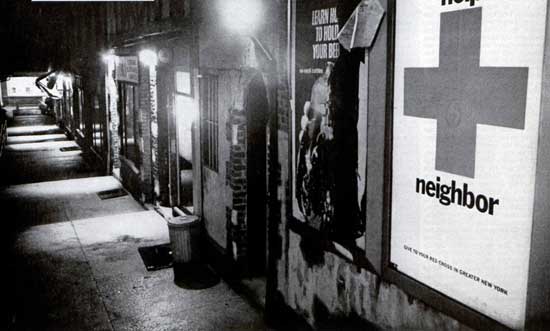

“Where fellowman would not help, a sign

now pleads for help. Moseley stalked his

victim in predawn darkness here, then

cut with a knife until she cried no more.” © SEPS 2014

Her murder prompted editorials across the country and around the world. Journalists denounced the increasing depersonalization of America.

Psychologists came up with explanatory theories, like the “Bystander Effect” (the theory that the greater the number of people witnessing an emergency, the less likely any one person is to act) and the “Kitty Genovese Syndrome”(the tendency of people in big cities to avoid social commitment.) The oft-repeated remark of one witness–“I didn’t want to get involved”–became emblematic of the times.

In 2004, a lawyer and resident of Genovese’s old neighborhood began to question the Times’ version of the murder. Joseph De May, Jr. thought the story was exaggerated. After studying the investigators’ reports and the crime scene, he concluded that 38 people simply could not have watched “a killer stalk and stab a woman in three separate attacks,” as the Times claimed.

We might feel more comfortable questioning the story today since the incident seems so out of character in America. In the half century following Genovese’s murder, we haven’t seen a trend of bystanders coldly watching somebody being attacked. On the contrary, Americans appear ready to help in emergencies ranging from traffic accidents to the Twin Towers on 9/11. Moreover, the annual murder rate in New York City has dropped significantly in 50 years, from 646 to 333. So, perhaps, the murder was not an example of New Yorkers’ growing indifference and fear as the 1964 Times article made it appear.

Genovese’s murder was exceptional in many regards, particularly its connection with another murder in Queens.

In July of the previous year, the parents of 15-year-old Barbara Kralik had found her, alone in her bedroom, stabbed repeatedly and close to death. Before dying at the hospital, Barbara gave a vague description of her attacker, which seemed to resemble Alvin Mitchell, a troubled teenager who had had known and often visited the girl.

Police interrogated Mitchell for 50 hours, until he confessed to killing Kralik. He then repeated the confession on camera.

“Alvin recanted the confession the next day,” the Post reported, “but the damage to his defense was already done. He insisted to his parents, his lawyers, and an examining psychiatrist that he was slapped, hit over the head with a phone book, threatened and frightened into making the admissions, but the protests were considerably weakened by the fact that he repeated the confession in front of a television camera….His defense would be that the confession was coerced. It was all the defense he had—until Winton Moseley confessed that he had killed Barbara Kralik.”

Moseley had been arrested when he was caught in the act of stealing a television. While detectives questioned him about the burglary, they noticed his resemblance to the neighbors’ description of Genovese’s attacker. One of the detectives abruptly asked him “Why did you kill Catherine Genovese?” Moseley replied, “I don’t know. I just had an urge to kill someone.”

He began to tell the detectives about the murder. After this confession, he admitted to a second killing. One of the detectives then said, “I suppose you’re going to tell us you killed Barbara Kralik too.”

“Yes, I killed her,” Winston Moseley said. “I stabbed her…six times…with a steak knife.”

Despite Moseley’s confession, and his obvious guilt in the Genovese stabbing, detectives didn’t believe his story. It had too many errors and inconsistencies. But Mitchell’s confession was also flawed. Both confessions seemed to carry weight, but neither fit exactly.

In the end, investigators in the Kralik case kept Mitchell as their prime suspect. And so, a week after Moseley went on trial for killing Genovese, Mitchell was tried for murdering Kralik.

In the Moseley trial, according to the Post, “There was never much doubt as to the…outcome. The jury found him guilty and then recommended the death penalty…a half-dozen women spectators suddenly began to applaud. Judge Shapiro angrily pounded for order and then, peering over his half glasses, delivered his own invective. “I don’t believe in capital punishment,” he told the jury solemnly, “but I feel this may be improper when I see this monster. I wouldn’t hesitate to pull the switch on him myself.” Moseley was sentenced to 20 years to life. (In November 2013, he was denied parole for the 16th time.)

Alvin Mitchell’s trial ended with a deadlocked jury. He was retried and found guilty, not of murder but of manslaughter.

A psychologist studying the cases noted that the Genovese and Kralik cases were highly unusual. They didn’t follow the expected pattern of homicide prosecutions. All the key players in the case, he said–the investigators, judge, court spectators, and defendants–“just didn’t act the way they are supposed to behave.”

50 years later, questions still remain regarding the accuracy of the New York Times story. Several investigations of the murder have concluded that it was a slow-to-respond police department that failed Ms. Genovese that night. Other reports say that many neighbors did in fact contact police after hearing the first attack, and later even tried to comfort Kitty as she lay dying.

While the actions–or lack thereof–of Genovese’s neighbors may still be in question, the narrative of an apathetic America took root. Neighborhood watch programs formed, an emergency telephone line (9-1-1) was established, and Good Samaritan laws were passed all at least in part as a result of the legend of Kitty’s unthinkable murder.