Considering History: The Cold War, the Korean War, and the Development of NATO

This column by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) was formed in the aftermath of World War II, as an attempt to establish collective defenses against emerging Cold War threats from the Soviet Union and its allies. Five Northern European nations (Belgium, France, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and the UK) began the process with the March 1948 Treaty of Brussels, and then brought their alliance to the United States and its Secretary of State George C. Marshall. With Marshall’s guidance those six nations, joined by Canada, Portugal, Italy, Norway, Denmark, and Iceland, signed the April 1949 North Atlantic Treaty, officially forming NATO.

Yet the Cold War of course extended far beyond the North Atlantic worlds, and NATO likewise was not limited to that sphere of influence. Indeed, it was in response to a Southeast Asian military conflict that began the following year, the Korean War, that NATO truly began to develop its international military forces and strategies, reflecting interconnections between these regions and issues that remain vital to this day.

While the Korean War’s background and origins were as complex and multi-faceted as any military conflict’s, the war began in earnest with North Korea’s June 25th, 1950 crossing of the 38th Parallel and invasion of South Korea. The United Nations Security Council unanimously condemned the invasion on the same day, and two days later President Truman ordered U.S. air and sea support for South Korean forces. By July 5th U.S. armed forces were on the ground and taking part in the Battle of Osan alongside South Korean troops, a military alliance that would continue for the remaining three years of the war.

While Truman and new Secretary of State Dean Acheson focused their initial public statements on the specific need to defend South Korea from the North’s aggressions, Truman very much believed that the war was part of larger Cold War conflicts as well. As he later argued in his memoir, Years of Trial and Hope (1956), “Communism was acting in Korea, just as Hitler, Mussolini and the Japanese had ten, fifteen, and twenty years earlier. I felt certain that if South Korea was allowed to fall, Communist leaders would be emboldened to override nations closer to our own shores. If the Communists were permitted to force their way into the Republic of Korea without opposition from the free world, no small nation would have the courage to resist threat and aggression by stronger Communist neighbors.”

NATO saw the Korean conflict and its ramifications in the same way, and responded accordingly. In September 1950 the NATO Military Committee called for a buildup of military forces to counter potential Soviet and allied aggressions around the world, and shortly thereafter the organization formed the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE), appointing Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower as its first leader. These efforts culminated in the February 1952 North Atlantic Council meeting in Lisbon, at which a number of key steps were taken: the creation of a Long-Term Defence Plan; the proposed expansion of combat-ready forces to 96 divisions (reduced to 35 the following year, which was still a significant increase); and the creation of a new Secretary General position, with the UK’s Lord Ismay appointed as the first NATO Secretary General.

NATO followed these efforts by undertaking its first major maritime exercise, Exercise Mainbrace, in September 1952. Although Eisenhower had by then resigned his position to run for the presidency, two American military officers and NATO leaders coordinated the exercise: General Matthew B. Ridgway, who had succeeded Eisenhower as Supreme Allied Commander Europe after commanding all U.S. and United Nations troops in Korea from 1951 to 1952; and Admiral Lynde D. McCormick, the Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic and himself a veteran of World War II’s Pacific Theater. Under their lead, more than 200 ships and 80,000 men participated in twelve days of military exercises, what New York Times reporter Hanson Baldwin called “the largest and most powerful fleet that has cruised in the North Sea since World War I.”

The headline of Baldwin’s article linked the exercises to NATO’s “Important Role in Defense of Europe.” Yet the exercise’s timing, along with Ridgway’s Korean War experiences and other overt links, made clear just how much the ongoing conflict in Korea served as a vital context and inspiration for these early 1950s NATO buildups and plans. By the July 1953 final armistice that ended the Korean War, NATO had largely become the sizeable, vital international military and diplomatic organization it would remain for the Cold War’s subsequent decades, one that, while centered in the North Atlantic, reflects a world in which Russia, Southeast Asia, and every region and nation are interconnected in the era’s issues and conflicts.

A New American Isolationism?

For the past century, the United States has frequently gone to war in the interests of freedom and democracy–often with the unstated (but not necessarily secondary) purpose of protecting our sources of oil or for access to populations who would buy our goods or services.

But the costs lately have become overwhelming, whether measured in cold, hard cash or in lives lost. America has lost its appetite to serve as policeman in the earth’s most horrific trouble spots. We just want to be left alone.

March 2014 marked the first month in more than a decade without a single American combat casualty anywhere in the world. For the vast mass of the American people, getting out of military entanglements is now the expectation rather than some vague hope. After two wars stretching back 13 years, American sentiment has once again tilted toward the isolationism that marked the end of the First World War. “[That conflict] was followed in the ’20s and ’30s by something that…was in fact a rejection of a certain role in the world,” says Robert Kagan of the Brookings Institution and a foreign policy advisor to Senator John McCain’s presidential campaign. “It wasn’t just, ‘Let’s have a little time out here.’ It was, ‘We are not going to be doing that.’”

In fact, it would take a challenge to our very way of life–in the form of Hitler, Mussolini, and that dastardly backdoor attack on Pearl Harbor–to draw us into World War II. And we never really emerged. The Korean War followed just a few years afterward, then it was on into Vietnam, and almost before we all realized what happened, we were on to the Balkans and Sarajevo; the Middle East, Iraq and Afghanistan; and now there’s Syria and Crimea and Ukraine.

And each such adventure has its own price tag. Iraq, a country from which we have already technically departed, is still costing us $3 billion per year. The overall Department of Defense budget totals some $496 billion, or 13.6 percent of the total federal budget today–and that’s with a rapidly shrinking military.

Compare these numbers to those of the Korean War, which cost us $30 billion ($262 billion in today’s dollars) or less than one-third of the cost of the post-9/11 war on terror that includes Iraq and Afghanistan, which the non-partisan Congressional Research Service puts at $859 billion.

With 20/20 hindsight, it’s beginning to look increasingly like our all but universally accepted role as the world’s policeman really peaked sometime during the Korean War. Then began a long, slow descent, largely perceptible only to the most astute observers positioned outside the Beltway. When John F. Kennedy sent us swaggering into the Indochina Wars at the very moment a far more nimble Charles de Gaulle was already extricating France, we were still operating under the assumption that America somehow had a higher calling we needed to fulfill. It seemed only America had the might, and the moral will, to prevent the rapid spread of that evil virus called communism across Indochina, into Thailand, down the Malay Peninsula and across Southeast Asia.

As it happens, I was present as a journalist to witness the final days of America’s foray into Southeast Asia. The final days and weeks of the takeover of Cambodia by the Khmer Rouge were not amusing. Seeing the conflict at this late stage, one forgot the original point of the American mission, to serve in a police capacity in this region.

But was that even an appropriate use of American power and influence? Neither in Korea nor in Vietnam nor in any other police action since–certainly not in Afghanistan or Iraq–has America had the kind of influence over the outcome envisioned at the start of our engagement. Our role was always presented to the public as a limited exercise: Act the role of the good cop, oust the bad guys, clap them in jail, then get the heck out of Dodge.

Of course, it’s never quite worked that way, and we have never learned our lesson. The failure derives not from a lack of good faith, but rather from a lack of vision. When we entered each of these rabbit holes, we never had a real understanding of how we’d emerge. As is clear now, the end game is in most respects far more significant than the entry point.

But if the American people have come full circle in the past century, arriving today at a reluctance for combat that mirrors post-World War I isolationism, many nations still look to the U.S. to play the role of global cop–if only because no other nation has the might or the will to play such a role. “I fear that what is going on now is that Americans are quite understandably not only tired of the burden, but they no longer understand the reasons why we even took on this burden in the first place,” Kagan says.

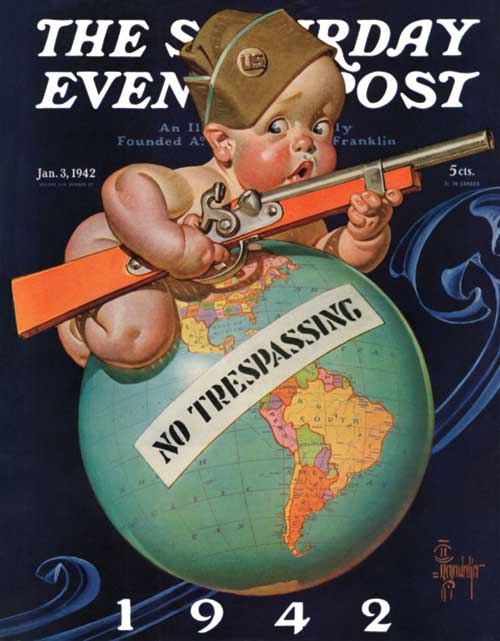

About those reasons: Sixty years ago, The Saturday Evening Post article “Can We Remake the World Without Going Broke?” observed that the nation’s Mutual Security Program, newly signed into law by Truman with bipartisan support in Congress, was staking the future of the American economy upon “the hope of revolutionizing the non-Soviet world.”

The piece continued: “This program pushes American military frontiers far out into Europe, Asia, and Africa. It consolidates an American pattern for reorganization of the entire non-Soviet world through combined military, economic, financial, and social measures.…It appeals to those who believe that ‘sharing our wealth’ is speeding up some form of world government.…On the other side, it appalls those Americans who are chiefly concerned with the radical changes which ‘mutual security’ means for the American traditional system: indefinite conscription of our young men, Federal expenditures greatly in excess of revenues, unparalleled taxes which are certain to increase, the overhanging threat of monetary inflation which already has reduced the purchasing power of the dollar by more than half.” (For more selections from the Post archive, see page 37.)