Are Women More Gullible Than Men?

Is it true, as W. C. Fields once said, that “you can’t cheat an honest man”?

A description of the top 10 con games seems to support the notion that dishonesty makes people vulnerable to con artists. In most of these operations, the victim’s greed, shame, or duplicity seem to make him an accomplice in his own swindling.

But if it’s true con artists can’t cheat honest men, why have they been able to cheat so many honest women? Why, for instance, was Raymond La Raviere so successful?

In the 1940s, La Raviere successfully played confidence games across the country without relying on his victims’ dishonesty. Their only fault, perhaps, was a desire for love and security.

He was arrested at a garage in 1948 when a police detective recognized him as a man wanted on a bigamy charge. Choosing to kill himself rather than face trial, La Raviere swallowed poison. While lying in a hospital, expecting to die, he made a full confession to a police officer. Over the past 10 years, he said, he had married 55 women and stolen $300,000 from them.

Unfortunately, the poison didn’t work. La Raviere was convicted and sentenced to eight years in jail.

As you’ll read in this article, running a romance scam was hard work. La Raviere had to keep moving from state to state, seeking wealthy single women. And, as you’ll read in the article, he had to stay continually in character, playing a wealthy bachelor from Alaska.

Once he had won a woman’s confidence — which never seemed to take long for him — La Raviere had to keep his latest fiancée from sharing the news with her relatives or friends. He swept his victims off their feet, into marriage, then away to the bank so they could open a joint account with her cash. After securing the money, he’d make a quick exit and was off to find a new mark.

Today, the business of wooing money out of women has become much easier and more profitable, thanks in part to the Internet and the $2 billion online dating industry.

Scam artists no longer need to marry to get at a victim’s money; they don’t even need to meet the victim. Instead, crooks can work in their bathrobe from the comfort of home, or in a cyber café in Malaysia. And they can work several victims at the same time.

Online romance scams have risen dramatically. In fact, the number of complaints doubled between 2013 and 2014, according to the Federal Trade Commission. Just between July and December of 2014, phony online admirers cheated Americans out of some $82 million — and these losses are probably underreported.

Of course, women aren’t the only victims — crime has always been an equal opportunity employer. But judging from stories reported in the media, the majority of the victims have been women.

Which raises the question: Are women, by nature, more easily fooled?

According to researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, and University of Pennsylvania, women aren’t more gullible. But they are more likely to be lied to.

The researchers came to this conclusion while observing MBA students practicing real-estate negotiations. Researchers found both men and women were more likely to lie to a buyer who was female than to a male.

The students told researchers they didn’t think women were more gullible, but they expected men would be more experienced negotiators and better able to spot a lie.

Believing that women had less skill in recognizing lies encouraged students to make false claims, the researchers concluded. “As a result, women are deceived more often than men.”

Which raises a second question. If women are more likely to be deceived, are men more likely to be deceptive? Here the research is less equivocal. Several studies agree that men lie more often than women: 50 percent more according to one British study.

According to these studies, the men don’t lie constantly; they appear to save their falsehoods for what they consider important matters. They are also more likely to justify unethical behavior and ignore the moral consequences of their actions.

While pondering the scope of male mendacity, you might want to know that Raymond La Raviere’s bigamy record was eventually shattered in 1983.

In that year, Giovanni Vigliotto, aka Nikolai Peruskov, aka Fred Jipp, was sentenced to 34 years for fraud and bigamy. In his testimony to the court, he confessed that he’d married and defrauded 105 women.

But given what we’ve been saying about men, should you believe him?

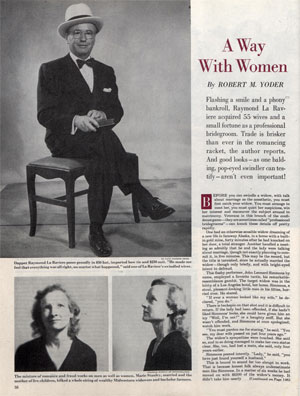

A Way with Women

This article was originally published in The Saturday Evening Post on May 7, 1955.

Flashing a smile and a phony bankroll, Raymond La Raviere acquired 55 wives and a small fortune as a professional bridegroom. Trade is brisker than ever in the romancing racket, the author reports. And good looks — as one balding, pop-eyed swindler can testify — aren’t even important!

Before you can swindle a widow, with talk about marriage as the anesthetic, you must first catch your widow. You must arrange to meet her, you must quiet her suspicions, win her interest and maneuver the subject around to matrimony. Veterans in this branch of the confidence game — they are sometimes called “professional bridegrooms” — can knock these details off pretty rapidly.

One had an otherwise sensible widow dreaming of a new life in faraway Alaska, in a home with a built in gold mine, 40 minutes after he had knocked on her door, a total stranger. Another handled a meeting so adroitly that he and the lady were talking about marriage, though not exactly planning to commit it, in five minutes. This may be the record, but the title is tarnished, since he actually married the widow — though only briefly, and with bright-eyed intent to defraud.

This flashy performer, John Leonard Simmons by name, employed a favorite tactic, his remarkable-resemblance gambit. The target widow was in the lobby of a Los Angeles hotel, her home. Simmons, a stout, pleasant-looking little man in his fifties, hurried over. He stared.

“If ever a woman looked like my wife,” he declared, “you do.”

There is backspin on that shot and it is difficult to return. If the lady had been offended, if she hadn’t liked Simmons’ looks, she could have given him an icy “Well, I’m not!” or a haughty sniff. But she wasn’t offended, and Simmons at once apologized; watch him work.

“You must pardon me for staring,” he said. “You see, my dear wife passed on just four years ago.”

The widow’s sympathies were touched. She said so, and in so doing managed to make her own status clear. She, too, had lost a mate, she said, only four years earlier.

Simmons peered intently. “Lady,” he said, “you have just found yourself a husband.”

This is bound to sound far too abrupt to work. That is because honest folk always underestimate men like Simmons. In a matter of six weeks he had moved on with $6,300 of the widow’s money. It didn’t take him nearly that long to get the money. He tarried because it was December; he seems to have figured that running out could wait until after Christmas.

Simmons could make the remarkable resemblance even greater, as he did in Long Beach, the quarry this time being a widow from Iowa. It was the season of the Rose Bowl. The hotel was packed and the tingle of gala events was in the air. The stout little man hurried toward the widow with a smile that said, “What a wonderful coincidence! Imagine running into you here.”

“Pardon me, madam,” he said happily. “You’re Mrs. Dunlap, aren’t you?”

His tone made it clear that Mrs. Dunlap was a fine woman to be, and the widow must have regretted having to deny it.

“No,” she said, “I’m Mrs. Dunham.”

“The resemblance!” Simmons marveled. “It’s simply amazing. Doctor Dunlap was our family physician, back in Colorado. I always thought highly of the Dunlaps. Why, one winter night, Doctor Dunlap came through a blizzard to save one of our children.”

Touche for Simmons, obviously. Everyone is in favor of doctors’ coming through blizzards to save children. What could Mrs. Dunham say, except “That’s nice,” or “Bully for Doctor Dunlap,” or “Children make a nice family”?

Simmons’ next move was to sit down. The widow sat too. She wasn’t Mrs. Dunlap, of course. Still, the names were close — Dunlap, Dunham. A small thing, but wonderfully effective in combating the word “stranger.” Not much trouble for Simmons either. Simply a matter of learning the lady’s name from the hotel help, and choosing another with a partial overlap.

Now Simmons told the widow all about himself —about his days in the stock market—highly successful— about his five mythical married children, one adopted. In a day or two, Mrs. Dunham was referring to Simmons, archly, as her “ boy friend.” That privilege cost her $1,300. Her niece contributed $5,000, two of the niece’s friends, $1,000 more. All thrust their money on Simmons eagerly, thinking he was letting them in on a big mysterious deal in wheat, with high profits and no risk.

The theory of the romancing racket is that many a widow would like to get married again if something very good came along. The swindler’s object is to woo the widow, win her, and then, when she is slightly dizzy from anticipatory whiffs of orange blossoms and wondering what to wear for a second wedding, to get her money or jewelry.

It might be called the gambling form of courtship, played for money. It is a fast game, one which keeps the swindler skating rapidly over thin ice all the way. Risking a prison term — Simmons is now serving a ten-year sentence—he bets his time and expenses that he can win, and usually he does. Not always. Simmons trailed one widow half across the continent only to find that she wasn’t wealthy at all, the deceitful thing. Fortunately, he had hooks baited for two at once, and the other was more trustworthy.

Men in this line of work have to be right in their estimate of what the victim wants, and they don’t put too much stock in the drawing power of romance, per se. They promise love and devotion, of course. But they also give the lady a peek at a well-stuffed wallet and lead her to expect a cushioned life several cuts above her present circumstances. Blue Heaven with a full-time maid, plenty of charge accounts, and a generous husband.

If the con men are right, a husband can have no more attractive characteristic— or perhaps the implication is that no characteristic is so rare. At any rate, generosity works like a charm, as can be seen from the short but busy career of a schemer named Joseph Levy.

Levy is a bad-check man. For years his favorite swindle involved posing as a prison official. A Baltimore episode is typical. Appearing at the offices of a firm which sold supplies to a prison in New York, Levy identified himself as the prison’s purchasing agent, and was given a warm welcome. He placed a large order, cashed a personal check, shook hands cordially and left. The check, of course, bounced.

Further to annoy the forces of law and order, he liked to pose as the warden of some state penitentiary, as a United States probation officer or as a United States attorney. He was always accepted without question though he had done time for forgery, larceny, the confidence game and theft from the United States mails.

By 1951 he was wanted in half a dozen states and it seemed imperative to change swindles. He shifted to courting widows and was an immediate success, not only with women his own age — again the middle fifties, the prime of life in this racket — but also with younger ones.

In the beginning, at any rate, fleecing widows seemed just right for Levy’s purposes, which were modest. Never greedy, he was simply out to make living expenses— board and room in the best hotels and enough cash to frequent the $50 window at the tracks. Relatively small contributions per widow would do.

His busiest year as a romancer was 1952. In February, in Detroit, he met Widow No. 1. In five days he had her dreaming of domesticity, but not in a little cottage with roses round the door. The swindlers never kid themselves that their charm will do the trick, and the invitation always is to something much better than love in a cottage. The marriage they offer, with a view to arousing a little greed, is clearly advantageous. Home in this instance was to be a handsome house on which the down payment was $18,000. The house would be Levy’s wedding gift to the widow. He gave her a check for $18,000, to make the payment, and asked her to cash a check of his own for $500. The disarming trick of seeming to give the victim far more money than you take was working faultlessly, as it always does. The widow gave Levy the $500, and as suddenly as he had blown into her life, he was gone, never to return. Both checks returned, however, being equally worthless.

Levy headed west, for the Coast. En route, he struck up an acquaintance with his second widow of the ‘52 season. Friends before the train reached Chicago, they were sweethearts by Albuquerque, and engaged on arrival in California. Illusionary husbands like Levy invariably are sweeter than the curmudgeons of real life, and—in a pretty gesture of liberality —Levy promptly opened a joint bank account. The widow contributed $500; Levy put in a manly, though wholly imaginary, $2,000. And so they were wed, but not for long. On Wedding Day plus One, Levy withdrew the widow’s $500 and was on his way.

That way led to Reno, where he spotted a beautiful diamond ring worth $6,000. The woman wearing it had a husband, and the husband was on hand. Courtship was out. Some other approach was indicated. Assuming a woman is all fixed up for love, what else will cause much the same happy confusion? Without hesitance, Levy chose “clothes.”

So Levy became a clothing tycoon from New York. Managing to meet the Lewises — we’ll call them that —he won such an in that when they left for California, Levy was riding with them. On the way, he pointed out how absurd it was for Mrs. Lewis to pay full retail price for clothes when she knew an insider like Levy. He had but to introduce her and she could enjoy the prices reserved for those in the know.

By the time they reached San Francisco, Mrs. Lewis could hardly wait to get to a department store. Levy spoke knowingly to the saleslady. “Show her nothing but the most expensive,” he directed. Mrs. Lewis was presently surrounded by a wonderful muddle of dresses and suits, and while she was, Levy borrowed her ring—to show it off to a store official, he said. Exit Levy, with ring, for keeps.

Levy had switched, briefly, from widows to rings. The logical next step was widow-with-ring, and Levy found one, that same month, aboard a train from Chicago to New York. He gave her a fast whirl in New York, urged her to make him the happiest man in the world, and she consented. As they talked of wedding plans, Levy said, “You’ll want an outfit,” and gave her (a check for) $2,000.

And while visions of sugar plums danced in her eyes, this most thoughtful of soon-to-be-husbands went farther. “You’ll want something better than that ring of yours, too,” said he. It was a good ring, worth $2,000. But if the dear man wanted to squander his money, why deny him? Riding by now on a pink-tulle cloud, the widow gave him the ring and cashed his check for $300. Levy left to get that shabby diamond replaced with something more like. And that is the last she saw of Prince Charming, now known in several states as Prince Charming, That Rat.

Summer found Levy at Tijuana. The world had turned full circle. The horses were betraying him again, and again he needed a widow with, say, $300. Levy has to succeed with skill and guile, not beauty. A man of medium height and build, he has graying brown hair, a big nose, a bald spot. His teeth protrude a bit and he has been unkindly described as popeyed.

So it says something for his craftsmanship that he took aim at a young woman this time, and was as successful as usual. She, too, said she would be his bride, and, more or less to bind the bargain, Levy deposited $2,500 to her bank account, in the form of one of his Yo-yo checks. Then he borrowed $500 from her and drove rapidly out of her young life — in her car.

Swindling widows sounds like a pleasant combination of business and pleasure, yet few make a career of it. Being a suitor day in and out, even for profit, may prove wearying. Levy had talent for it; he was especially good at creating the illusion of marriage-just-ahead, putting the girls in the exciting role of bride-to-be. Yet, after seven successful swindles in a row, he gave it up for something less demanding.

Posing as a big wheel from innermost Washington, he called spurious checks in the manner pioneered by Frederick Emerson Peters, one of the elite of the impostors. This consists of buying expensive gifts and having them sent to prominent citizens, who are presumably the shopper’s intimate friends. He pays by bad check, and the change is his profit.

Levy’s prominent citizens were prominent, all right. He bought perfume to be sent to Mrs. Eisenhower, Scotch for the President, golf clubs to be sent to Vice-President Nixon. With the clubs went a pally note: “Dick: beat the boss.”

It was a nice touch, but just about Levy’s last. Widows were screaming for his throat, shopkeepers were demanding restitution, and what with one thing and another, Levy assembled so many complaints that he was elected to the FBI’s Most Wanted Criminals list. National fame would have been his had he managed to elude arrest one day longer. As it was, FBI agents sighted him at Churchill Downs — at the $50 window, of course—on April 30, 1953. They were carrying descriptive material which was to be released to newspapers on May first, and here was the hero himself.

So the announcement that he had made the Most Wanted never got published. This is a shame, in a way, for the news of his success with women would have been encouraging to all men who are something less than beautiful. “Neither spectacular in performance nor impressive in physical appearance,” said the FBI, “he is appealing, experienced and self-confident. He relies on artful impersonation and finesse to overcome his physical handicaps.” It goes to show that looks aren’t everything, even when this fine old game is played for money.

About twice a year the FBI nails a fugitive and it is announced that he has swindled two, three or four widows, making a career of it. Now living in the Midwest, enjoying his first freedom in some years, is a man to whom a three-or- four-widow career must sound like a two-strawberry shortcake.

Raymond La Raviere is, or rather was, the most remarkable operator ever to enter this field because of his distinctive way of getting the ladies’ money. He didn’t just hint at marriage; he married them. One after another after another. A red notebook which fell into the hands of the law listed 50 women, all of whom he had wedded by age 44. And there was a notation which said, “Forgot five — happened so fast — last names.”

La Raviere’s techniques, which he told a jailer had netted him $300,000, became known largely because of a razzle-dazzle courtship in St. Paul. He had two approaches: the fast one, in which he proposed marriage inside of an hour or so after first meeting; the slow one, in which he waited a day or two. In St. Paul, he used the quick one.

The problem was to meet a likely widow, get her confidence and her money, and be gone. La Raviere managed it handily inside a week. He used a favorite opening gambit. That was a newspaper ad saying that a “refined business gentleman” sought a room with refined surroundings in a private home.”

Among those with a room to spare for a refined business gentleman was a 55-year-old widow who may be called Mrs. Larkin. She answered the ad by letter. At ten the next night the refined gentleman called —a rather short man in the middle forties, well dressed. A little fussy about his living quarters, he said the room was a bit overcrowded, but with certain minor changes, he would take it. He introduced himself. Horner was the name. He was a mining engineer, he said, employed by a mine in Alaska —a gold Mine. He had staked out a claim of 180 acres, built a cabin on it. He didn’t exactly say there was gold on his claim, but the widow felt impelled to remark that she, too, owned property —or had until she recently sold it. Horner said that for all his job and his claim, he wasn’t happy. He was a widower, and had recently lost his only daughter in a tragic fire. The widow said she, too, knew the pangs of loneliness. At that, Horner said firmly that she need never be lonely again. “I will take you back to Alaska with me,” he vowed.

“I suppose you do need a housekeeper,” the widow said.

“Housekeeper!” said Horner. “You shall be my wife.”

And with that, the warm breeze from the frozen north blew back to his hotel. “Meet me with your answer tomorrow night,” he said on leaving.

It left the widow a little goggle-eyed. She had a job, but she stayed home the next day to ponder this strange turn of events, so like something in a book. At the hotel, that evening, Homer asked her to come to his room for a minute. She noted that his possessions were those of a man of means, and to make sure she didn’t miss this point, Horner quoted prices. In the few minutes of her stay, he managed to show her his luggage —$300 the piece— his $600 overcoat, his portable radio with custom-made carrier, at $150. He then took her to an expensive dinner and was masterful with the waiters, sending everything back to the kitchen at least once.

Horner was moving his things to the widow’s spare room that night. In the cab, going out, he pressed for an answer to his proposal, promising that as his wife she should have the best of everything. The widow, overwhelmed, said she would marry him. It was just under 24 hours after their meeting.

Next day Horner exhibited a money belt fat with bills and commanded his bride-to-be to go buy herself a splendid trousseau. At this point the ordinary man would have to transfer some of his cash from money belt to fiancée. Homer skipped that stage. The widow bought, but the widow paid.

State law decreed a five-day wait before marriage. To the impetuous Alaskan, that was intolerable. He took Mrs. Larkin to South Dakota and married her there — four days after he had knocked on her door. Now he wanted a honeymoon in New York. “We’d better put our money in a joint account,” he said. “What’s mine is yours.” The bride had $6,900 in her account. “Don’t withdraw it all,” said Homer. “Just six thousand.”

The bank teller counted out the money for the bride, but Horner’s hand got there first, and he put the bills in his wallet. The bride also cashed in securities worth $3,200. This money he let her keep, temporarily.

On the train to Chicago, first leg of the New York idyll, Horner counted the $6,000. “That teller made a mistake,” he said grumpily. “There’s a thousand-dollar bill here. I asked him to put it in hundreds. I’d better count the money the broker gave you.” He counted the $3,200, declared it was all in order, and put it in his money belt. But he gave his bride $50 just for pin money, as a token of how things were going to be.

In the waiting room in Chicago, Horner excused himself to see about their reservations. He didn’t come back, and there were no reservations. Police took the bewildered Mrs. Horner to the FBI. The competence of Horner’s performance — giving the widow a flash of a money belt, a glimmer of Alaskan gold; being fussy about the room to show he had his small faults — told the FBI men that here was a pro.

So they asked around: did this story strike a chord anywhere? In the state of Washington it did. A man of this description had operated there; his name was Raymond La Raviere. But there was still nothing to indicate the remarkable scope of La Raviere’s romancing, and there might never have been if chance — or a bonehead play — hadn’t brought him back to St. Paul.

With Mrs. Larkin’s money and that of other victims, La Raviere had bought a home in Long Beach, California, intending to retire. He had it coming; he had been getting married four or five times a year for thirteen years. But he couldn’t stand inactivity. In thirty days, traveling in a swanky car with black body, gold top and winecolored upholstery, he hit the road again. He paused in St. Paul to get the splendid car serviced, was spotted by a detective and shortly wound up in jail.

Looking into his background, the FBI turned up first one, then two, then eighteen other marriages. When this news became public, three additional wives sang out; so did four women La Raviere had swindled without marriage. As La Raviere went on trial for swindling Mrs. Larkin, a small army of wives trouped in.

Too much was too much. When court reconvened after lunch, La Raviere pretended to blow his nose and swallowed bichloride-of-mercury tablets concealed in his handkerchief. In the hospital, supposing he was dying, he said the notebook total was right: he had married at least 55, here and abroad. In a day or two, this most devoted of short-term husbands always sent the bride shopping or to a beauty parlor, and was long gone when she came home.

To La Raviere’s chagrin, he failed to die, but by then it was too late to retract his confession. There was nothing to do but plead guilty; the sentence was eight years. In the next few weeks a meticulous fourteen of his wives got annulments.

A way with women is an interesting gift and there seems no doubt that La Raviere had it. But what was it that got his wives? Some spoke of his “distinguished appearance,” his “beautiful white teeth.” One said he seemed to hypnotize her; she thought he used a drug. Perhaps the finest tribute to his salesmanship came from the wife who said, “He made me feel that everything was all right, no matter what happened.”

These descriptions suggest a pretty overwhelming fellow. Actually — or so any man would bet — what did the trick for La Raviere was that he looked vastly sincere, thanks in part to a brow both high and wide. In the movies, he would have been cast as the good brother, the one who pitches hay in the hot sun while the wicked brother chases the neighbor girls.

He was a good product; he looked reliable, upright and not too good to be true; he looked like first-rate husband material. And along with this, the man knew his market and his business. The widows in these cases are by no means nitwits. They are likely to say, “What do I know about this man, anyway?” La Raviere’s description of himself was plausible enough and hard to check, this side of Alaska. It was easier to take him at face value.

The lady might reasonably want to meet his family. He had that stopped too. The family he described consisted of a dear old aunt, in some faraway city, and an equally imaginary brother. A splendid character, the brother; so splendid he was unavailable. A missionary, La Raviere explained, in China.

The fact that La Raviere could meet a widow and marry her four days later doesn’t mean his work was easy. It was a thing which had to be done at racing speed or not at all. Widows have friends, and friends are likely to be suspicious of Alaskan gold-mining engineers who drop out of nowhere. Friends can raise doubt and urge caution, may even do a little investigating.

So the swindler has to cut his victim out of the herd, keep her absolutely isolated, keep her too busy to think, too busy to take advice. She will want to show him off. He tells her that three is a crowd, urges her to keep their plans in romantic secrecy. He can’t let down; he has to be with her every possible minute, not only to show devotion but to keep her from seeing others. One of the few times La Raviere failed was when one of the victim’s friends began asking skeptical questions — and at the last minute too.

The widow who says indignantly, “We are not all such easy marks,” is right, of course, but she underestimates the artistry with which these traps are laid. The swindler is anything the lady wants: owner of a string of race horses, if she is a lively sort; retired plumbing contractor, if she wants something quieter. La Raviere sometimes posed as the owner of a gambling house in Hawaii. John Leonard Simmons was usually a capitalist, but he also did well in the modest role of retired streetcar motorman — cleaning up in goods salvaged from railroad wrecks. And in any role the swindlers will of course be plausible; that’s their business.

Since marriage does not hold quite the same enchantment for men as for women, professional brides, the female equivalent of the Simmonses, Levys and La Ravieres, ought to starve. They don’t. The same mixture of romance and fraud works with men, and it doesn’t take a walking dream, either. Marie Stanley made it pay and, while pretty, Marie was old enough to have a married daughter.

In Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, North Dakota and Minnesota, Marie swindled a whole string of wealthy widowers and bachelor farmers. The theory of her operation was this: A man will not mind lending a girl a large sum of money if (a) he expects to get it back quickly, and (b) it will enable the girl to get a much larger sum of money, which (c) presumably will fall into the lender’s hands, as (d) will the girl herself — as his propertied bride. If the girl is not an outright hag, this is a pretty good deal, or would be if real.

An Ohio episode shows Marie at the top of her form. She drove into the yard of a farm owned by a bachelor who flew a plane; she figured the plane signified money. Marie introduced herself as a magazine writer, out to do a piece on flying farmers. There were several sessions and it wasn’t hard to convince the farmer that life would be much more exciting with Marie around permanently.

But Marie had a business deal she had to conclude before she could settle down to wedded bliss. She owned a dress shop in Detroit — sometimes it was a beauty parlor or hardware store. She was about to sell it for $45,000. The only hitch lay in paying off a $9,000 mortgage. For this, Marie was a little short — by $5,600.

What’s $5,600 to lend a girl who is about to bring you $45,000? The farmer gave Marie a cashier’s check. Marie kissed him good-by and joined her husband, William, the father of her five children, in the family trailer, then in Lima, Ohio. The flying farmer never saw Marie again until he and brother victims met her in Federal court.

Marie’s victims were sensible, hardheaded men who had held their own in many a business deal. Yet an Illinois farmer loaned her $2,500, a widower in Indiana sold his hogs to lend her $2,450, a grain speculator in Sioux Falls was taken for $3,500, a young Minnesota farmer for $5,000.

With so many waiting to testify, things looked dark for Marie when finally she was brought to trial. But she made a valiant try. Swindle? What swindle? She had been a bad girl, she was willing to admit, but not a swindler. These men had given her money, yes. But there had been no talk of business, only of love. The money, she blushed to say, was in return for her favors. She had resisted the gentlemen’s sinful advances every time, but hadn’t won a game all season.

The United States attorney, however, assailed this as make-believe piled on make-believe. The tender moments Marie described never took place, he said; having conned the victims, Marie was now trying to con the jury. Unfortunately for Marie, he could destroy her story in her own words. She had told FBI men that she always made the suckers keep their distance, figuring that to say “No” enhanced her desirability.

Swindling widows in the guise of a dream husband come true entails risks. The swindlers are likely to fall afoul of Federal law and get the FBI on their heels. This happens if they cross a state line with loot worth $5,000 or more, or if they cash, in one state, a worthless check drawn on a bank in another.

Talented performers come to grief. Simmons, Levy and Marie Stanley are now in prison; La Raviere only recently got out. These bearish factors are not expected to put a serious crimp in the racket, however. It’s a swindle that’s bound to flourish, because it is own cousin to the truth.

The plausible strangers tell the widows some fancy lies, of course. But in courtship, a little exaggeration is expected on both sides, and it arouses no very deep suspicion. The number of widows is at an all-time high; the market for devoted and well-heeled, middle-aged husbands never was better. And a widow can’t question a suitor too closely; he might be on the level and resent it.

The trouble is, nobody looks more on the level than a good con man. FBI agents thought they had spotted a fugitive in a Los Angeles cafeteria. They had seen many photographs and read pages of description, but even so, they were not at all certain that this substantial-looking citizen was the man they wanted — until he told them so himself, inadvertently. Strolling along downtown streets after lunch, aimlessly and absently, he came to an office building not visibly different from any other. But suddenly be seemed to remember it, and not favorably. Putting on dark glasses, he cut through a parking lot. At these helpful signs of a guilty conscience, the pursuers closed in. The building he had shunned houses the Los Angeles offices of the FBI.

THE END