When Elvis Flopped in Vegas

In a town addicted to building things, blowing them up, and then building them all over again, the New Frontier Hotel in 1955 was a fine example of Las Vegas progress. It was originally built in 1942 and called the Last Frontier, the second resort to open on what would become known as the Las Vegas Strip. Like its predecessor, El Rancho Vegas, the Last Frontier was a luxury resort in old Western garb — “The Early West in Modern Splendor,” as its promotional slogan put it.

But as ever more modern and luxurious hotels opened along the Strip, the Last Frontier decided it was time for an update, and in early 1955 the hotel closed down, gave itself a makeover, and reopened as the New Frontier. The old Western-themed showroom was transformed into the spiffy new thousand-seat Venus Room, with five tiered rows of booths and an expansive stage, “with sides running to such length that the whole thing looks like a gigantic cinemascope screen,” in the words of one awed reporter.

The hotel’s grand reopening in April 1955 was something of a disaster. Mario Lanza, the internationally renowned opera singer and movie star, was booked as the opening headliner, but he suffered a meltdown before the show — an attack of stage fright compounded by drinking — and never set foot onstage. After an hour’s delay, the hotel announced that Lanza had laryngitis, and Jimmy Durante appeared as a last-minute replacement. (Too last-minute for Las Vegas Sun columnist Ralph Pearl, who filed his review early to make his deadline and raved about Lanza’s phantom performance. “Seldom in the history of this town,” he wrote, “has a star done a greater show or received a greater standing ovation.”)

One year later the New Frontier played host to the Las Vegas debut of another, very different performer. He was nervous, too, but he did show up — though many in the audience were probably mystified as to what he was doing there. On April 23, 1956, Elvis Presley came to town.

The 21-year-old rockabilly sensation from Memphis was in the midst of his phenomenal breakthrough year. Elvis Aron Presley recorded his first RCA single, “Heartbreak Hotel,” in January. By April he had the No. 1 record in America; his gyrating TV appearances, on Tommy Dorsey’s variety show and The Milton Berle Show, were the talk of the country; and Paramount Pictures had signed him to a movie contract.

“No check is any good,” said Elvis’s manager Colonel Tom Parker. “They’re testing an atom bomb out there in the desert. What if someone pushed the wrong button?”

Elvis appearing in Vegas was his manager Colonel Tom Parker’s idea, and not a very good one. Elvis’s frenetic rock ’n’ roll performances, which were causing such a sensation in the rest of the country, were hardly geared for a crowd of middle-aged Vegas showgoers. Yet there he was at the New Frontier, touted as “The Atomic-Powered Singer” (in a town where people could watch real atomic tests taking place in the Nevada desert nearby), the “extra added attraction” on a bill headed by Freddy Martin’s orchestra and comedian Shecky Greene. Elvis got paid $15,000 for the two-week gig, and the Colonel asked for it in cash. “No check is any good,” he said. “They’re testing an atom bomb out there in the desert. What if someone pushed the wrong button?”

The audience at the New Frontier must have thought someone had pushed the wrong button. Freddy Martin, whose “sweet music” orchestra was known for its pop versions of classics like Tchaikovsky’s Concerto in B-flat, opened the show with several of his instrumental hits and a medley of songs from the musical Oklahoma! Next came Shecky Greene, a Chicago-born comedian just gaining notoriety for his raucous Vegas lounge act. Elvis was the closing act. Backed by his three-piece rhythm group — guitarist Scotty Moore, bassist Bill Black, and drummer D.J. Fontana — Elvis performed four songs and was onstage for just 12 minutes. The response was polite at best. One high roller sitting at ringside, according to a witness, got up midway through the show, cried “What is all this yelling and noise?” and fled to the casino. The critics weren’t much kinder. “Elvis Presley, coming in on a wing of advance hoopla, doesn’t hit the mark here,” wrote Bill Willard in Variety. “The loud braying of the tunes which rocketed him to the big time is wearing, and the applause comes back edged with a polite sound. For the teenagers, he’s a whiz; for the average Vegas spender, a fizz.” Newsweek said the young rock ’n’ roller was “like a jug of corn liquor at a champagne party.”

For Elvis and his backup group, accustomed to the pandemonium they were causing in concerts across the country, the response was sobering. “For the first time in months we could hear ourselves when we played out of tune,” said Bill Black. “They weren’t my kind of audience,” Elvis would say later. “It was strictly an adult audience. The first night especially I was absolutely scared stiff.”

Shecky Greene got friendly with Elvis during the run and could see that the kid was out of his element — unable to relate to the audience and lacking the stage experience to win them over. He didn’t even dress right. “He came out in a dirty baseball jacket, just shit,” Greene recalled. “I went to Parker and I said, you can’t let him come out on the stage like that.” The Colonel apparently took Greene’s advice; for the rest of the engagement, Elvis and his band wore neat sport jackets, slacks, and bow ties. But after the first night, they no longer closed the show. Shecky Greene did.

By happy chance, a recording of Elvis’s 1956 Vegas show exists — taped by an audience member on the last night of the two-week engagement. Freddy Martin makes a polite, if rather patronizing, introduction, noting that it’s Elvis’s last performance: “We hate to see him go; he’s a fine young lad and a fine talent.” Elvis opens his set with “Heartbreak Hotel” — slower and bluesier than the recorded version, with Elvis playfully changing the lyric to “Heartburn Motel” in the last verse. His patter with the audience is disarmingly modest; Elvis is acutely aware that he’s a fish out of water. “We’ve got a few little songs we’d like to do for you,” he says at the outset, “in our style of singing — if you want to call it singing.” He alludes to the difficulties he’s been having in the engagement: “It’s really been a pleasure being in Las Vegas. We had a pretty hard time — uh, a pretty good time. …” He makes a few awkward, country-boy jokes, asking the orchestra at one point if they know his next song, “Get Out of the Stables, Grandma, You’re Too Old to Be Horsin’ Around.” After three more numbers — “Long Tall Sally,” “Blue Suede Shoes,” and “Money Honey” — it’s over.

Elvis’s only chance to connect with his real audience came on a special Saturday matinee, scheduled by the hotel expressly for the teenagers who weren’t allowed into the casino for the evening shows. For a $1 admission (the proceeds donated to a local Little League baseball program), the kids got a free soft drink and a chance to shower Elvis with the kind of screaming adulation he was getting almost everywhere but in Las Vegas.

“The carnage was terrific,” reported Bob Johnson in the Memphis Press-Scimitar. “They pushed and shoved to get into the 1,000-seat room and several hundred thwarted youngsters buzzed like angry hornets outside. After the show, bedlam! A laughing, shouting, idolatrous mob swarmed him; he fled to the insufficient sanctuary of his suite. The door wouldn’t hold them out. They got his shirt, shredded it. A triumphant girl seized a button, clutched it as though it were a diamond. A squadron of police had to be called in to clear the area.”

The door wouldn’t hold them out. They got his shirt, shredded it. A triumphant girl seized a button, clutched it as though it were a diamond.

A few of the old-timers in Vegas tried to get hip to the new music phenom. “This cat, Presley, is neat, well gassed and has the heart,” wrote Ed Jameson in a tongue-in-cheek column for the Las Vegas Sun titled “A Cat Talks Back.” “His vocal is real and he has yet to go for an open field. He is hep to the motion of sound with a retort that is tremendous. These squares who like to detract their imagined misvalues can only size a note creeping upstairs after dark. This cat can throw ’em downstairs or even out the window. He has it.”

Though it was a tough engagement for him, Elvis enjoyed Las Vegas. He didn’t gamble much, but he checked out other entertainers in town (among them Johnny Ray, the Four Aces, and Liberace), went to the movies, and rode the bumper cars at the Last Frontier Village next door. He kept company with Judy Spreckels, a sugarcane heiress from Los Angeles, and Vampira, the campy TV horror-show host who was appearing in Liberace’s show at the Riviera. An Elvis fan from Albuquerque, Nancy Kozikowski, was on a vacation in Las Vegas with her parents and ran into Elvis several times during her stay — in the hotel lobby, at the restaurant, and one afternoon when he was wandering alone at the Last Frontier Village. “He recognized me and was very nice,” she recalled. “We took pictures in the 25-cent picture booth together and alone. We also made a very funny talking record together. … Elvis was very nice, very gentle, a perfect gentleman.”

Elvis’s first visit to Las Vegas had one unexpected by-product. Among the lounge acts Elvis went to see was Freddie Bell and the Bellboys, a sextet from Philadelphia that did a kind of slicked-up, finger-snapping, nightclub-friendly version of early rock ’n’ roll. (The group had a bit role in the movie Rock Around the Clock, which had just opened in theaters.) One of the highlights of their show was an up-tempo version of “Hound Dog,” a blues number that had been a hit in 1953 for Willie Mae (“Big Mama”) Thornton. Elvis was so taken with Bell’s performance that he began doing the song in his own act and recorded it later that summer. “Hound Dog” became Elvis’s fastest-selling record yet, and his signature hit.

His 1956 Las Vegas engagement is regarded by most Elvis chroniclers as a rare misstep in a year of meteoric success, otherwise orchestrated to perfection by Colonel Parker, the onetime carny promoter and manager of country star Eddy Arnold who became Elvis’s manager and career guru early that year. The Colonel would later defend the booking, saying it gave Elvis a chance to reach a new audience and pointing out that the New Frontier couldn’t have been too disappointed, since the hotel asked him back for a return engagement.

Shecky Greene — who thought Elvis was a “wonderful kid” but turned down an offer from Colonel Parker to tour with Elvis as his opening act, finding the prospect faintly absurd — never quite understood what all the fuss was about. One day he ran into Bing Crosby, who was in Vegas during Elvis’s engagement. “What is the thing about this kid?” Shecky asked the elder statesman of American pop singing. “He’s a nice kid, but …”

“Shecky,” Bing replied, “he’ll be the biggest star in show business.”

Excerpted from Elvis in Vegas: How the King Reinvented the Las Vegas Show by Richard Zoglin. Copyright © 2019 by Richard Zoglin. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Featured image: ScreenProd / Photononstop / Alamy Stock Photo

Paul Anka: Doing It His Way

Singer-songwriter Paul Anka remembers the first check he received after his recording of “Diana” soared to the top of the pop charts. The amount was $300, modest even by 1957 standards, but “it seemed like a lot of money to a kid coming off a paper route in Canada,” says Anka, who was 16 at the time. Unlike many one-hit wonders whose success was short-lived in the early days of rock and roll, Anka had the savvy and talent to stay ahead of the trends. The music he wrote soon evolved from sock-hop ballads like “Puppy Love” to big-band standards like “My Way,” created for his mentor and close pal Frank Sinatra.

“Frank and Sammy [Davis, Jr.] looked after me, watched over me, and allowed me into their circle,” he says of the legendary entertainers. The “circle” was Sinatra’s famed Rat Pack, and members included Dean Martin, Peter Lawford, and Joey Bishop. Sinatra gave them all nicknames, which were embroidered on the robes they wore when they lounged around the saunas and pools at the Las Vegas hotels where they performed. Anka, decades younger than the rest of the Pack, emerged as The Kid. The name stuck, although “as I got older and after I wrote ‘My Way,’ the mentoring thing became more of a friendship,” he says.

With an active concert schedule and a new CD in the works, Anka doesn’t dwell on nostalgia, although a couple of current projects have him rummaging through his files and pulling out photos, clippings, and programs from the past. If everything goes according to plan, 2009 is going to be a big year. His autobiography, still untitled, is scheduled for an autumn release, and he’s in preliminary talks about a Broadway show based on his 50-year career.

At age 67, The Kid is on a sentimental journey, recalling the times he traveled with Elvis, hung out with Buddy Holly, popped up on American Bandstand, and wrote a theme song for Johnny Carson. And then there was Ole Blue Eyes….

We’ll begin there.

The Post has uncovered an interesting photo of you, Frank Sinatra, and a monkey. Is there a story behind the picture?

Actually, it was an orangutan. We were in Vegas, and Frank’s friends were throwing a birthday party for him. I remember thinking, What do you give to a guy who has everything? So I went to the circus that was playing at a nearby hotel, and I said, ‘Let me borrow the orangutan.’ It was fitting because back then the atmosphere in Las Vegas was all about the prank. I marched into the party with the orangutan and gave it to Frank. Little did I know that in those days he was wearing a very bad toupee, and [in photos taken that night] the monkey’s hair looks better than Frank’s.

Of the more than 900 songs that you’ve created, “My Way” may be most memorable. What motivated you to write the words that became Sinatra’s signature signoff?

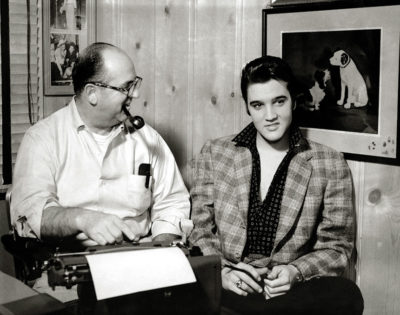

We were at a dinner in Florida when he announced his plan to retire. The Rat Pack had dissipated and he was tired. He said he would make one more album, and then he wanted out. That moved me to go home, imagine myself in his place, and write what would be the retiring song for someone who was the premier artist of all time. I used to do everything on the typewriter — I could type 60 to 65 words a minute — and so I just rattled away from one a.m. until I finished it around five. The song became a turning point for both of us. I remember I was in New York when he called me from the studio in Los Angeles and played it for me for the first time over the phone.

Let’s talk about the early days, the ’50s and ’60s, when you toured with some of the pioneers of rock and roll. What was it like to travel with these great artists — many of them African-American — at a time when some venues didn’t welcome people of color?

I remember that period in great detail. Coming from Canada, it was very difficult for me to understand segregation. I was close to the Platters, Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, and the others. Consequently, I was taken aback by it. We were close because of the music, but the situation drew us even closer. I remember refusing to eat at places that wouldn’t serve them. I was part of the team and we were very protective of each other. It was a time of great camaraderie.

How did your parents feel about their son going into show business at such a young age? Did they encourage you?

Things were different than they are now. A lot of parents today are sophisticated and start training their kids at age four or five because with shows like American Idol, they know what’s at the end of the rainbow. They understand the possibilities. But that wasn’t the case for us. Television started at five in the afternoon in Canada, and the programming was limited. People really didn’t have their arms around the music yet. My parents were dealing with the unknown — and a kid who was focused and aggressive about what he wanted. They were very concerned when I borrowed some money and went off to New York. Then I called them and said, “Come on down and sign my contract.” They were dazzled by it … and so was I.

You’re working on your autobiography now, piecing together five decades of history. What’s it like to go back in time and recall all that you’ve seen and done?

It’s been cathartic and sentimental. I’ve kept all my memorabilia…all the letters, articles, itineraries, and pictures. I have 50 years’ worth of material, so it’s really a process of editing out what I feel is not important or what I’m not willing to reveal. The memories come back, maybe not the details, but the meat is there when I look at the pictures and read the letters. I can remember what was going on and the people I was meeting.

And now there’s the possibility of a Broadway show…. Do you have a performer in mind to play Paul Anka as a teenager?

Yeah, I like the young kid who was on American Idol [David Archuleta], but there would have to be someone else. My real dream stroke is Robert Downey, Jr. His energy and capabilities are what I envision. That would be the coup of the century.

The music you’ve created over the decades is so varied that it can’t be tucked into a pigeonhole or given a label. How do you continue to stay up on the trends? When you’re in the car with the radio on, what do you like to listen to?

A lot of everything. There’s so much good stuff out there; my taste is eclectic. I listen to Madonna, Elton John, Yo-Yo Ma, Alicia Keys, Tim McGraw…. I have to be aware of what’s going on. I’m always learning something. I can’t come from a limited point of view of not embracing all music. I think that’s a mistake. Some artists are pretty highfalutin about what they do. That’s not me. I like country music a lot…I love the lyrics; I think country is the purest American music; that and jazz. As a musician I get a little something out of all of them.

Obviously you’re not thinking about retiring. Your last couple of albums did well, and you’re headed into the studio for another. Will it be classic Anka or new material?

I’m coming off of the success of Rock Swings [album released in 2005]. That went gold in many markets and gathered a new audience for me. I’m playing to 20,000 and 30,000 people in some cases, and 30 to 40 percent are under age 35. A lot of that is because of Rock Swings. I don’t know if I want to stay on that page, because I’ve done it. The next album may be newly written material from my observations at this stage of my life. My last album took me at least nine months to finish. You can’t rush something like that. Everything looks like it will happen in 2009.