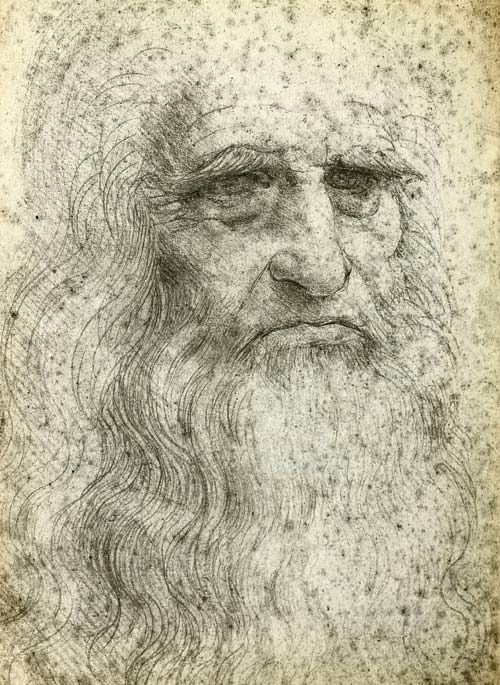

20 Life Lessons from Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci was a genius, one of the few people in history who indisputably deserved — or, to be more precise, earned — that appellation. Yet it is also true that he was a mere mortal.

The most obvious evidence that he was human rather than superhuman is the trail of projects he left unfinished. Among them were a horse model that archers reduced to rubble, an Adoration scene and battle mural that were abandoned, flying machines that never flew, tanks that never rolled, a river that was never diverted, and pages of brilliant treatises that piled up unpublished. “Tell me if anything was ever done,” he repeatedly scribbled in notebook after notebook. “Tell me. Tell me. Tell me if ever I did a thing. … Tell me if anything was ever made.”

Of course, the things he did finish were enough to prove his genius. The Mona Lisa alone does that, as do all of his art masterpieces and his anatomical drawings. But we can also appreciate the genius inherent in his designs left unexecuted and masterpieces left unfinished. By skirting the edge of fantasy with his flying machines and water projects and military devices, he envisioned what innovators would invent centuries later. And by refusing to churn out works that he had not perfected, he sealed his reputation as a genius rather than a master craftsman. He enjoyed the challenge of conception more than the chore of completion.

—Leonardo da Vinci

What also distinguished Leonardo’s genius was its universal nature. The world has produced other thinkers who were more profound or logical, and many who were more practical, but none who were as creative in so many different fields. Some people are geniuses in a particular arena, such as Mozart in music and Euler in math. But Leonardo’s brilliance spanned multiple disciplines, which gave him a profound feel for nature’s patterns and crosscurrents. His curiosity impelled him to become among the handful of people in history who tried to know all there was to know about everything that could be known.

The fact that Leonardo was not only a genius but also very human — quirky and obsessive and playful and easily distracted — makes him more accessible. He was not graced with the type of brilliance that is completely unfathomable to us. Instead, he was self-taught and willed his way to his genius. So even though we may never be able to match his talents, we can learn from him and try to be more like him. His life offers a wealth of lessons.

1. Be curious, relentlessly curious. “I have no special talents,” Einstein once wrote to a friend. “I am just passionately curious.” Leonardo actually did have special talents, as did Einstein, but his distinguishing and most inspiring trait was his intense curiosity. He wanted to know what causes people to yawn, how they walk on ice in Flanders, what makes the aortic valve close, how light is processed in the eye, and what that means for the perspective in a painting. Being relentlessly and randomly curious about everything around us is something that each of us can push ourselves to do, every waking hour, just as he did.

2. Seek knowledge for its own sake. Not all knowledge needs to be useful. Leonardo did not need to know how heart valves work to paint the Mona Lisa. By allowing himself to be driven by curiosity, he got to explore more horizons and see more connections than anyone else of his era.

3. Retain a childlike sense of wonder. At a certain point in life, most of us quit puzzling over everyday phenomena. We might savor the beauty of a blue sky, but we no longer bother to wonder why it is that color. Leonardo did. So did Einstein.We should be careful to never outgrow our wonder years, nor to let our children do so.

4. Observe. Leonardo’s greatest skill was his acute ability to observe things. It was the talent that empowered his curiosity, and vice versa. It was not some magical gift but a product of his own effort. When he visited the moats surrounding Sforza Castle, he looked at the four-wing dragonflies and noticed how the wing pairs alternate in motion. When he walked around town, he observed how the facial expressions of people relate to their emotions, and he discerned how light bounces off different surfaces. This, too, we can emulate. Water flowing into a bowl? Look, as he did, at exactly how the eddies swirl. Then wonder why.

5. Start with the details. In his notebook, Leonardo shared a trick for observing something carefully: Do it in steps, starting with each detail. A page of a book, he noted, cannot be absorbed in one stare; you need to go word by word. “If you wish to have a sound knowledge of the forms of objects, begin with the details of them, and do not go on to the second step until you have the first well fixed in memory.”

6. See things unseen. Leonardo’s primary activity in many of his formative years was conjuring up pageants, performances, and plays. He mixed theatrical ingenuity with fantasy. This gave him a combinatory creativity. He could see birds in flight and also angels, lions roaring and also dragons.

7. Go down rabbit holes. He filled the opening pages of one of his notebooks with 169 attempts to square a circle. In eight pages of one notebook, he recorded 730 findings about the flow of water; in another notebook, he listed 67 words that describe different types of moving water. He measured every segment of the human body, calculated their proportional relationships, and then did the same for a horse. He drilled down for the pure joy of geeking out.

8. Get distracted. The greatest rap on Leonardo was that these passionate pursuits caused him to wander off on tangents. But in fact, Leonardo’s willingness to pursue whatever shiny subject caught his eye made his mind richer and filled with more connections.

9. Respect facts. Leonardo was a forerunner of the age of observational experiments and critical thinking. When he came up with an idea, he devised an experiment to test it. And when his experience showed that a theory was flawed — such as his belief that the springs within the earth are replenished the same way as blood vessels in humans — he abandoned his theory and sought a new one. If we want to be more like Leonardo, we have to be fearless about changing our minds based on new information.

10. Procrastinate. While painting The Last Supper, Leonardo would sometimes stare at the work for an hour, finally make one small stroke, and then leave. “Men of lofty genius sometimes accomplish the most when they work least,” he explained, “for their minds are occupied with their ideas and the perfection of their conceptions, to which they afterward give form.” Most of us don’t need advice to procrastinate; we do it naturally. But procrastinating like Leonardo requires work: It involves gathering all the possible facts and ideas, and only after that allowing the collection to simmer.

11. Let the perfect be the enemy of the good. When Leonardo could not make the perspective in the Battle of Anghiari or the interaction in the Adoration of the Magi work perfectly, he abandoned them rather than produce a work that was merely good enough. He carried around masterpieces such as his Saint Anne and the Mona Lisa to the end, knowing there would always be a new stroke he could add. Likewise, Steve Jobs was such a perfectionist that he held up shipping the original Macintosh until his team could make the circuit boards inside look beautiful, even though no one would ever see them. Both he and Leonardo knew that real artists care about the beauty even of the parts unseen. Eventually, Jobs embraced a countermaxim, “Real artists ship.” That is a good rule for daily life. But there are times when it’s nice to be like Leonardo and not let go of something until it’s perfect.

12. Think visually. Leonardo was not blessed with the ability to formulate math equations or abstractions. So he had to visualize them, which he did with his studies of proportions, his rules of perspective, his method for calculating reflections from concave mirrors, and his ways of changing one shape into another of the same size. Too often, when we learn a formula or a rule — even one so simple as the method for multiplying numbers or mixing a paint color — we no longer visualize how it works. As a result, we lose our appreciation for the underlying beauty of nature’s laws.

13. Avoid silos. Leonardo had a free-range mind that merrily wandered across all the disciplines of the arts, sciences, engineering, and humanities. His knowledge of how light strikes the retina helped inform the perspective in The Last Supper, and on a page of anatomical drawings depicting the dissection of lips, he drew the smile that would reappear in the Mona Lisa. He knew that art was a science and that science was an art. Whether he was drawing a fetus in the womb or the swirls of a deluge, he blurred the distinction between the two.

14. Let your reach exceed your grasp. Imagine, as he did, how you would build a human-powered flying machine or divert a river. Even try to devise a perpetual-motion machine or square a circle using only a ruler and a compass. There are some problems we will never solve. Learn why.

15. Indulge fantasy. His turtle-like tanks? His plan for an ideal city? The man-powered mechanisms to flap a flying machine? Just as Leonardo blurred the lines between science and art, he did so between reality and fantasy. It may not have produced flying machines, but it allowed his imagination to soar.

16. Create for yourself, not just for patrons. No matter how hard the rich and powerful Marchesa Isabella d’Este begged, Leonardo would not paint her portrait. But he did begin one of a silk-merchant’s wife named Lisa. He did it because he wanted to, and he kept working on it for the rest of his life, never delivering it to the silk merchant.

17. Collaborate. Genius is often considered the purview of loners who retreat to their garrets and are struck by creative lightning. Like many myths, that of the lone genius has some truth to it. But there’s usually more to the story. The versions of Virgin of the Rocks and Madonna of the Yarnwinder and other paintings from Leonardo’s studio were created in such a collaborative manner that it is hard to tell whose hand made which strokes. And his most fun work came from collaborations on theatrical productions and evening entertainments at court. Genius starts with individual brilliance. But executing it often entails working with others.

18. Make lists. And be sure to put odd things on them. Leonardo’s to-do lists may have been the greatest testaments to pure curiosity the world has ever seen.

19. Take notes, on paper. Five hundred years later, Leonardo’s notebooks are around to astonish and inspire us. Fifty years from now, our own notebooks, if we work up the initiative to start writing them, will be around to astonish and inspire our grandchildren, unlike our tweets and Facebook posts.

20. Be open to mystery. One day Leonardo put “Describe the tongue of the woodpecker” on one of his eclectic and oddly inspiring to-do lists. The tongue of a woodpecker can extend more than three times the length of its bill. When not in use, it retracts into the skull and its cartilage-like structure continues past the jaw to wrap around the bird’s head and then curve down to its nostrils. When the bird smashes its beak repeatedly into tree bark, the force exerted on its head is 10 times what would kill a human. But its bizarre tongue and supporting structure act as a cushion, shielding the brain from shock.

There is no reason you actually need to know any of this. It is information that has no real utility for your life, just as it had none for Leonardo. But maybe you, like Leonardo, want to know. Just out of curiosity. Pure curiosity.

From Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson. Copyright © 2017 by Walter Isaacson. Rerpinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Walter Isaacson is a professor of history at Tulane University, a celebrated journalist and biographer, and author of the New York Times bestsellers Leonardo da Vinci; The Innovators; Steve Jobs; Einstein: His Life and Universe; Benjamin Franklin: An American Life; and Kissinger: A Biography.

This article is featured in the May/June 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.