Having a Pen Pal Is Good Medicine

When Steven Kamla responded to an advertisement for a pen pal in the back of Teen Magazine in the early ’80s, he could not have known then that he’d be laying the foundation for what would become a lifelong friendship. Nor could he have imagined that pen-to-paper communication, nearly four decades later, would be rendered a lost art thanks to marvels known as email and Snapchat. But that’s what happened to Kamla, a teen from Wisconsin who is now a 52-year-old hair stylist in San Francisco. He estimates that he and his pen pal, Mohini Mistry, who lives outside of London, England, have exchanged close to a thousand letters. The two have met several dozen times too, but despite advanced technology, they are sticking to their old ways.

“I’ve never thought of emailing her as that was never our relationship,” says Kamla. “I didn’t even have her email until six months ago, and we are still adamant about continuing to write.”

As teens, the duo talked about school and family and gushed over clothes and their favorite music. They even sent magazine pictures and badges depicting their favorite bands (Duran Duran, Wham!, Soft Cell, Michael Jackson). As they grew older, their friendship deepened, and they navigated topics such as college and jobs, health issues, and even personal hurdles such as when Mistry’s parents, both Hindu, planned to arrange her marriage. Mistry wrote to Kamla, revealing that she planned to tell them she wanted to live her life and be with someone she loved. She’s been married to her English husband, Garry, for 31 years now, and Kamla, along with Mistry’s parents, attended the wedding.

“I had my friends and work colleagues, but I always wrote Steven more about my feelings,” Mistry says. “Even though he was in America, he understood me more than anyone and he has remained a constant in my life.”

Also thinking of the people who shaped her life was Nancy Davis Kho, the author of The Thank-You Project. In 2016, the year she turned 50, Davis Kho set out on a pen-and-paper gratitude journey and wrote 50 thank-you letters to friends, coworkers, teachers, exes, doctors, and family members, including her father, who framed the letter and hung it above his desk. Davis Kho’s father passed away unexpectedly later that year, but knowing that she’d put her words of love and thanks down on paper for him provided comfort. “So much of our communication is digital now, and nothing sticks around. But by putting something into the physical artifact of a letter, there’s a permanence that allows you and your recipient the opportunity to really savor the sentiments within.”

There are plenty of studies on the positive benefits of writing, including one by social psychologist James W. Pennebaker, a pioneer on the subject and a professor at the University of Texas, Austin. He’s also the author of Opening Up: The Healing Power of Expressing Emotion and Writing to Heal, in which he details evidence that expressive writing heals physically and emotionally. Davis Kho found this to be absolutely true. By virtue of seeking things to include in her letters, she says she enhanced her positive recall bias — the ability to notice positive things rather than negative things first — and fostered a greater sense of forgiveness in cases where she’d held on to old hurts and resentments.

“What has surprised me most about writing letters is how much differently I express myself and how much deeper I am able to go.”

“The thank-you letters made those things recede into the background, and I think they strengthened my sense of connection and community,” she says. “People who received my letters certainly understand better how much I care for them, and they treat me accordingly.”

With, on average, 2.26 billion people using Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, and Messenger each day to communicate, it’s easy to shoot off meaningless words, angry or otherwise, without a second thought, and forget about them just as quickly. For Kamla, letter writing has prompted a journey of self-discovery. “What has surprised me most about writing letters is how much differently I express myself and how much deeper I am able to go,” he says. “I can slow down and take the time to think about what I want to say. It’s therapeutic in a way. And knowing I will have Mistry’s full attention when she’s reading makes me more thoughtful about my words.”

For our hyperconnected culture, the concept of “losing touch” is a hard one to grasp. But during the pre-computer, pre-cheap phone plan world, letters were the instant messages of their day, and a link to friends far away. This was true for Raffi Darrow, 44, of St. Petersburg, Florida, and her best friend Rivki Yellin. The two met in San Jose, California, and spent first and second grade together before Yellin and her family moved to Staten Island. They spent the next 15 years writing back and forth, sending Scooby-Doo stickers and recounting stories of boyfriends and movies, and later weddings and children. Darrow says they don’t write letters anymore, opting for the ease of phone calls and instant photos, but the letters were the glue that kept their friendship together.

Something else today’s rapid-fire technology can’t deliver and the instant-gratification culture misses out on? The sweet sensation of anticipation. “Waiting was unbearably exciting. There was nothing like opening the mailbox and seeing that physical letter. It’s hard to explain this to my kids now,” Darrow says. “I felt important and loved every time I got a letter from Rivki, and I know she felt the same way.”

Darrow still has all her letters, as does Mistry. And Davis Kho made copies of the ones she sent knowing that one day, they will be signposts of her younger days.

“It will be so lovely to look back at your correspondence from the vantage point of an older age and be reminded of who you were, and who and what mattered to you.”

This article is featured in the May/June 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Pen Pals with the Killer of Kitty Genovese

Years later, Winston Moseley would describe it as a robbery that went wrong.

He claimed he’d never seen Kitty Genovese before, and he had no intention of harming her.

But when she saw him on the morning of March 13, 1964, in her New York neighborhood, she started to run away. Moseley said, “I kind of lost my head.” He pursued her and then stabbed her twice. Crying for help, she collapsed to the ground. A neighbor, hearing her cries, shouted out his window, demanding to know what was going on. Moseley ran away, and the neighbor saw Genovese rise and walk into her apartment building. Once inside, she collapsed on the entryway floor.

After getting away from the scene of the crime, Moseley slowed and thought. And then he went back to his victim and killed her. The murder became infamous for the number of witnesses to the crime who did nothing to help her (although many of the facts in the New York Times story that appeared two weeks after her murder were later questioned and found to be grossly exaggerated). Still, 55 years later, the murder is remembered as an example of what can go horribly wrong when everyone thinks, “I shouldn’t get involved.”

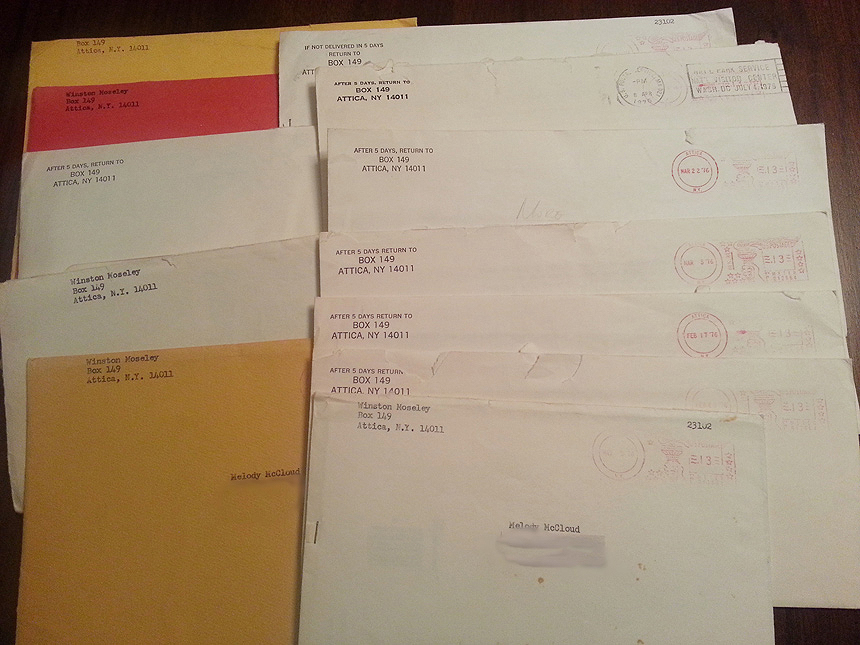

One woman who got involved — albeit inadvertently, and years later — was Melody McCloud. Moseley’s account of his murder of Genovese is detailed in a series of letters he wrote to McCloud, then a pre-med student at Boston University.

While still in school, she’d been involved in a prison ministry, sharing the message of forgiveness and redemption with prisoners. Later, in 1975, she saw a television news story about Moseley, in which he was identified as “Inmate Liaison to Attica Correctional Facility.” He told the reporter he was working to improve conditions for prisoners following Attica’s deadly riot in 1971. Although Moseley was a total stranger, McCloud wrote him a letter of encouragement in his liaison work. The next month, she received a letter back from him, and a correspondence began.

Over the next five months, he wrote twelve letters. Some included poems or cards. It was in his third letter that he wanted her to know about his conviction “right from the start so you can decide whether or not the facts…are going to make any difference to you.” He told her that he was the murderer of Kitty Genovese in 1964 and once escaped from custody.

The name “Genovese” sounded familiar. She recalled that the case had been a big deal at the time. She looked up details in the library and discovered that Moseley had confessed to murdering two other women — Barbara Kralik and Annie May Johnson — and was accused of forty robberies and various assaults and rapes.

McCloud was stunned by what she read. She recalls thinking, “What’s a nice girl like me doing in a story like this?”

She wrote back to Moseley about what she’d learned. He responded to her questions about Kralik. He also described, at length, his mental state the night of Genovese’s murder.

He’d felt defeated by his two divorces and separation from his children. His parents, to whom he was very close, had been having serious problems for years. He wrote that it created “a psychological disturbance for me.”

After attacking Kitty and running away, he wrote, “what I went back for was some vague notion of taking her to a hospital.” After putting on a wide-brimmed hat to avoid recognition, he returned to her apartment building. He found Kitty on the floor of her building’s entry. When she saw him, he claimed, she began using abusive, racist language. In his letters, he wrote “I stopped being human.” Overcome with hatred, he attacked her again, stabbing her repeatedly while she called for help.

Moseley wrote that he didn’t feel hurried because he knew no one would come, no one would interfere.

“I didn’t want to get involved,” was reported to be a common excuse of the witnesses. The incident gave rise to a new, sinister, phenomenon: “bystander syndrome,” a symptom of urban life in which people abandoned their sense of responsibility and human connection.

In response, residents of New York City began neighborhood watch patrols. And the city established the first 911 system for calling the police.

Later investigation contradicted the claim of 38 inactive witnesses. Moseley said the number had been exaggerated to make the crime sound worse. It was certainly bad enough, becoming the most infamous murder in a year that saw 630 murders in New York. But this crime magnified New Yorkers’ fear that they couldn’t count on others for help in an emergency.

Less than a week after murdering Genovese, Moseley was captured while burgling a house. He confessed to the murders of Genovese, Kralik, and Johnson.

After learning the details about Moseley’s past, McCloud continued to write, but not as often. She began easing away from the correspondence, telling him she was too busy. “How can you be so busy you can’t write?” he challenged in his next letter. He was angry, she says, and he added threateningly, “you better be careful!” In a later letter, he apologized for his anger.

Their correspondence ended in May of 1976.

Moseley remained in prison until his death in 2016. During his 52 years in prison, he had applied for, and was denied, parole 18 times.

While Moseley lived, McCloud, who is now an obstetrician-gynecologist and author who lives in Atlanta, Georgia, did nothing with the letters.

Today, her collection of letters offers a unique insight into the mind of a serial killer, made even more valuable for their candor. “I was not anyone who could really help him,” she says. “I was just a kid, basically. So I don’t feel he had anything to gain by lying to me about his psychological state.”

For 43 years, Dr. McCloud has held onto these letters, not wishing to publicize them while Moseley lived. This year marks the 55th anniversary of Genovese’s death. It’s time, she says, to share their contents.

Feature image credit: Courtesy Dr. Melody McCloud. Used with permission.