North Country Girl: Chapter 1 — Duluth

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

In Duluth, a tiny dot on the western tip of that great lake Superior, where I had the good fortune to grow up, each season had its own smell. Spring was definitely here when the purple and white lilacs burst forth, their pervasive old lady fragrance signaling that there would be no more snow and it was time to switch out our house’s storm windows for screens, a twice-yearly job my father dreaded. I held the ladder beneath him, trembling as the “Goddamits!” and “This is horseshits!” rained down.

Summer was the sharp green nose-tickle of new-cut grass, which I loved until I was at an age where the lawn-mowing duty fell on me. I was scared to death of the power mower and its whirling blades, as if it were some kind of wild beast that could wrench itself away and roll over my feet or go after my sisters playing on the other side of the house. In the tidy, upper middle class neighborhoods of Duluth, the lawn had to be mowed weekly to create a perfect carpet of grass. In summer, that grassy scent was always in the air, as dads who were busy playing golf during the weekend would be pushing their lawn mowers back and forth in the long summer twilight after work. A neglected yard meant something inside the house was not right.

Fall was burning leaves, which was done as often as possible purely for the joy of it. Starting in September, stolid Duluthians turned into pagans celebrating the autumn equinox. Every yard up and down Lakeview Avenue was heavily treed and leaves started falling on Labor Day, with the last ones letting go around Halloween. Great piles of dead leaves were amassed in the curbs every fall weekend and we kids would bury each other in them; that dead leaf smell was dry and papery and mingled nicely with the rich, tobacco-y smoke from the piles already burning. Raking the yard was a family project: everyone big enough to hold a rake was given one. Raking was about as permissive parenting as I ever saw growing up. If a little kid did nothing but scatter the leaves further around the yard, a bigger person would patiently follow behind and rake them up again. Once the leaves were configured into huge piles in the streets, we were allowed to jump in, strew them about, and have them cheerfully re-raked again for additional jumping. When the autumnal shadows lengthened east, the last leaves were given a final pile-up and set ablaze. The leaves vanished into smoke and it was time for dinner.

Winter was the bracing iciness of falling snow and cold, a scent that almost wasn’t one, a scent that would freeze your nose hairs together every time you inhaled. This was a wonderful smell if I were ice skating or playing broomball or tobogganing, a miserable one if I was sent out to shovel ten-foot drifts of snow from off our front sidewalk.

***

I was five, too young for yard work when we moved into our first Duluth house, in the Woodland neighborhood. It was a tiny yellow ranch, identical to the neighbors’ on either side except for color. The house was set on a small, almost treeless lot, so there were no piles of autumn leaves to jump in. The smell I remember from that house was sheep shit, which our left side neighbor slathered over his lawn as fertilizer all spring and summer.

The previous owner of our house had planted raspberry canes in the back yard, which had grown into a massive thicket that inflicted a scratch for every berry picked. Down the street was the Woodland Drug Store, with a small soda fountain along the side. My dad took our one car to work, so when I got bored of hanging around our empty yard, and started ordering my little sister Lani to search for raspberries, my mother frog marched Lani and me there for a fountain Coke, a rare treat, as my dentist father did not allow pop at home. As much as I enjoyed the cherry cokes, I loved even more twirling myself around and around on a chrome and red stool till the drug store become a blur and my head swam and my eyes crossed. That combination of sugar and dizziness was my first high.

To get to the drugstore, we had to pass by the St. James Orphanage, which looked as formidable as it sounds. I was terrified of that building and the luckless children who lived there. It was as frightening as if it were the St. James Home for Retired Ogres. Up till then, I had thought that orphans were fairy tale creatures, like elves and witches; the idea of losing not one but both parents was scary enough to send me running to the bathroom to pee the second we got to the drug store.

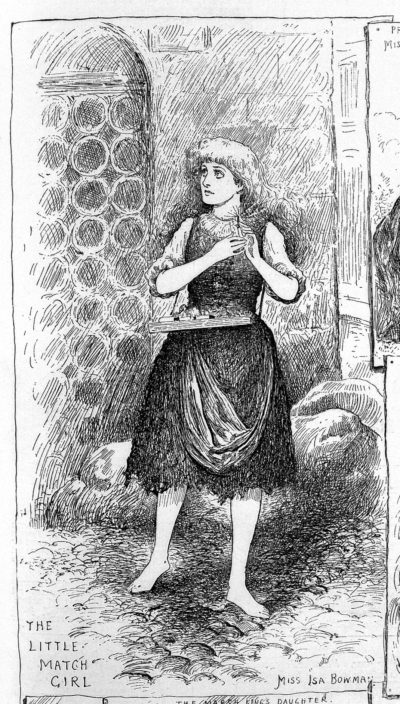

The St. James Orphanage may have inspired my conviction, every time my parents went out at night, that something dreadful would happen and I would never see them again. Or it may have been that I was a morbidly sensitive child. I had a book of Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales that was missing both “The Little Match Girl” and “The Little Mermaid.” The orphaned, window-peeking Match Girl watches a happy family gathered round their Christmas tree, uses her last match to try to keep warm, and then freezes to death on the street. The Little Mermaid, after months of feeling as if she were walking on knives on her new feet, bestowed by the sea witch in exchanged for her voice, sees her beloved Prince marry somebody else, dies, and is turned into a bit of foam because she doesn’t have a human soul and so cannot go to heaven. I couldn’t read either story without bursting into inconsolable sobs so my mother’s expedient solution was to tear the gloomy pages out of the book.

My sister, the feral child Lani, did not move into the Woodland house at the same time as the rest of us. She had been dispatched months before to our maternal grandparents in Aberdeen, South Dakota, while my parents looked for a place to live. Lani had been born in Hawaii, where my dad had spent two years in the army, pulling teeth out of soldiers on Schofield Barracks in Honolulu. Now we were all back in Minnesota (except for the exiled child), and he was ready to start his adult civilian life, in his own practice, and needed to find a home for his cute blonde wife and daughters.

My dad, mom, and I were camped at the other grandparents in Carlton, a town of 400 people half an hour outside of Duluth. My South Dakota grandmother, Nana, loved children, the younger the better, and had unending patience and tolerance for noise and mess. Grandma Marie, my dad’s mother, was only interested in clothes, her golf game, bridge, and daily Mass. While my dad was at work, and my mother stuck driving around with real estate agents looking at houses, I could be safely parked on the sofa with a book, or let out to explore the acres of woodland and plum orchard that surrounded my grandparents’ house. The lovely orchard would later be sacrificed by my grandfather to build a bomb shelter big enough for the entire town of Carlton to wait out a nuclear attack.

My frantic, difficult one-year-old sister was another story. An early and avid walker, she was Houdini-like in her ability to escape adult custody, and would have raced across the wide front lawn in seconds to get to the busy two-lane county road, a road that claimed a dog a year from my grandparents. Lani also cried non-stop and was an even pickier eater than I was. My grandma Marie was not about to give up mass, golf, or bridge to babysit such a creature. Lani was sent off to join the gaggle of grandchildren in Aberdeen, retrieved several months after we had moved into the Woodland house.