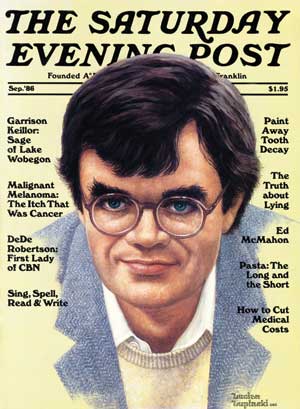

Garrison Keillor

A little more than 40 years ago, Garrison Keillor launched a live radio variety show with the self-consciously modest, Midwest-retro title A Prairie Home Companion about the fictional town of Lake Wobegon, “where all the women are strong, all the men are good-looking, and all the children are above average.” About 12 people showed up in the audience that first time. But something about his smart (but never smart-ass) humor — delivered in Keillor’s faintly sibilant, slow rumble of a voice — struck a nerve. And the show, equal parts music, mayhem, and monologue, became a cult hit.

Keillor never expected the show to last, much less turn him into a public figure. “I was brought up by church people,” he says. “We were not in show business. My parents brought me up thinking it was wrong to go to shows. Then suddenly I became one.”

Today, millions read his books and poems and crowd his live performances. As his loyal fans know, he’ll be hosting his final show this July, but he’s still got lots to say, so he’ll be writing and touring and, as he puts it, “musing.” A new book of Keillor’s monologues will be published soon. Now, wearing his signature red socks, he has declared that he intends “to rediscover lunch and weekends.”

Jeanne Wolf: When you created this monster all these decades ago, did you have any idea how big it would become?

Garrison Keillor: I had no idea what I was doing. I was a writer looking for a social life, an enormous problem for me. I was brought up evangelical fundamentalist in a group called the Plymouth Brethren, and we were taught to separate ourselves from the world. I spent six years in college, which gave me a certain arrogance. In my early 30s, I was painfully lonely, and picked up the idea for doing a live weekly variety show, with a steady stream of musicians and performers and tech people, and we became friends, work friends. I sat alone at a typewriter all week, and on Saturday there was this big party with me as the host. I could’ve joined a church or a bowling team or found a therapist or done all three, but the radio show pulled me through.

JW: People all over the world started tuning in to your party. Look what you created.

GK: I was a writer who was looking for something interesting to do. I’m an English major. An English major is, you know, imbued with these rather grand ideas of writing novels and short stories. But I’m not that good at that. So I needed to find something else to do. And this was it.

JW: Your fans and followers marvel at your many gifts and talents. They are astonished at your stamina. What drives you? What fuels your continuing passion, creativity, and work ethic?

GK: The fear of failure is a powerful motivator. People pay money to come see my show, or they donate money to their public radio stations, and when I walk into the theater, I’m struck by how hard the crew worked to get all the gear in place — the set, the speaker system, the lights, the mixing boards, the monitors. I dread the thought of doing a show that is flat and tuneless and done by rote. The thought of disappointing stagehands is miserable. And then there are the people who share my last name.

JW: As you contemplate doing the final show, what are your plans? Will the format be the same?

GK: I arranged that show so I get to sing all my favorite duets with my favorite duet partners. It is a fine way to wind up.

JW: The show goes on with a new host; you will now be executive producer. How involved will you be? Will you be a guest on the show?

GK: I don’t want to lay the heavy hand of the past on the young man, so I won’t be involved much at all. Chris Thile (the new host) is a free spirit, and he needs to spread his wings and jump off the roof.

JW: How will your life change from the way it is now?

GK: I’ll live at my own pace, get up early, take a brisk half-hour walk, come home, pour a cup of coffee, do the Times crossword, and settle in at the computer. No big deadlines pounding on the walls. And when I get the urge to visit my relatives in L.A. or Chapel Hill or Greenville or London, I’ll just go do it. Life is short, and mine is even shorter.

JW: Your summer tours are wonderful things. Can you offer your fans hope for more?

GK: I loved the summer tours, traveling around in a bus, sleeping in a bunk, singing with the band, walking out into the crowd on a grassy slope on a summer night and singing with them — “O beautiful for spacious skies” and “Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord” and “She was just 17, if you know what I mean” — so if people still want to do that, I’m game.

JW: Your monologues that deal with winter, and especially ice fishing, are particularly evocative. The hilarious stories about driving a Winnebago out on the lake ice — are these pure invention or are they based on personal experience?

GK: I’m cautious by nature, but I’ve seen large RVs driven out onto a lake and can imagine various outcomes, and that’s where the Winnebago story came from. The boy who drove it onto the ice was trying to impress his high school pals, and there was beer involved, and it was late and they fell asleep, and in the morning there was open water and he had to gun the engine hard, and the transmission chewed itself to bits and the frame got bent, and then he had to face his father. None of that was based on personal experience. It was based on dread. I’ve been ice fishing a few times, and those few times served as the basis for numerous monologues. I have no need to do it again.

JW: Lake Wobegon has always touched us with nostalgia for a time and place that seems a little distant. These days, it can seem like it’s on another planet. Is America changing dramatically for better or worse?

GK: America has been changing since the first Europeans arrived in the 17th century, and probably before that. Compared to the Revolution, the Civil War, the Great Depression, and World War II, the changes of the past 20 years have been fairly slight. But we now have a thousand times more outlets for expressing and amplifying our fear and discontent, so it sounds like a revolution, whereas it’s only a hailstorm. Our basic values are as strong as ever, and much stronger than in the 19th century, for example, when half the men in the country were schnockered half the time — and much stronger than during the era of slavery, which was a shame on the culture. There’s a lot of melodrama and self-pity going on, but it’s still America.

JW: Frustration, anger, and disillusionment bubbles up from the American public as the presidential race dominates our news. We can’t exactly recapture the so-called “simpler times.” What are your thoughts about our nation’s future?

GK: Politics has never been so crazy as now, thanks to the real-estate promoter from New York, and I’ll be happy when fall comes around and we get serious.

JW: As you look back on the ups and downs of success and fame, are there key people who stand out?

GK: Bob Altman, who directed the movie of A Prairie Home Companion, was an inspiration, an 80-year-old man who loved his work and meant to march on until he couldn’t anymore. Chet Atkins was a great man who grew up poor in East Tennessee and fell in love with a Sears Silvertone guitar and with music he heard on the radio, jazz mostly, and it dawned on him that if you could play guitar like Django Reinhardt, you’d become part of a natural aristocracy. Even if you were puny and had big ears and spoke with an accent and came from the sticks, you’d be an artist, which includes southern, northern, black, white, city, and rural. And anybody with sense would recognize it. I’m honored to have known him and Bob and other artists like them. It’s not about fame, it’s about the work.

JW: Do you feel very different from the guy we wrote about in The Saturday Evening Post in 1986?

GK: That guy was flushed with success and romance, having written a big bestseller and married his Danish sweetheart from high school. The marriage ended in sadness, and I am a better man for having gone through it. Less full of myself. More grateful for the simple, good things of life.

JW: When you hear your parents’ voices in your head, what are they saying?

GK: My mother is saying, “Be careful.” My dad is saying, “What are you waiting for?”

JW: If you could go back in time, what advice would you give yourself as a kid growing up in Minnesota? What did he learn? What would he like to do over?

GK: I’d tell him to learn carpentry and plumbing and go find work. Skip college and just read the classics. Get a life and then maybe try his hand at writing.

JW: What are you most grateful for?

GK: Grateful to be alive. Life is good. Every day, even the bad ones.